Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

Founded in 1986, the Melbourne Writers Festival (MWF) celebrates words and stories, hosting writers from around the world in August each year. For the last couple of years, Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) has been proud to hold Festival events related to history writing and archives at the Victorian Archives Centre in North Melbourne.

This year, the program has gone virtual, so though we can’t host an event at the Victorian Archives Centre in 2020, we can share with budding writers the value of our collection right here. Whether you’re writing historical fiction, historical crime or non-fiction works, we have incredible resources to inspire and inform your work.

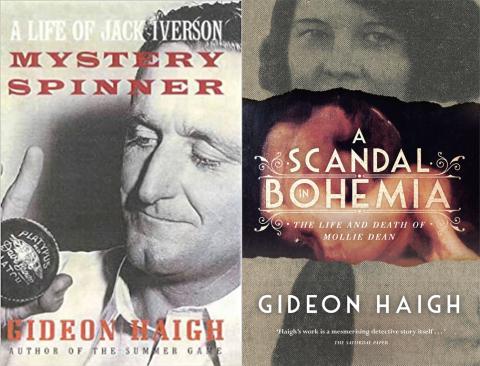

For MWF 2018, journalist and author of 40+ books Gideon Haigh, hosted a practical workshop at the Victorian Archives Centre where he shared how public records can inform writing about historical periods of Victoria. We asked him to share some of his experiences with our collection to help inspire other writers this year.

Warning some of the records and stories we discuss in this article relate to death and trauma and may be upsetting for some readers.

How things have changed

When Gideon first delved into public records there wasn’t as much material online and access required a stop along the way to our old building in Laverton.

“I was looking at the death of the first test cricketer, a man called Billy Midwinter who's very interesting, he played cricket for Australia versus England and England versus Australia and he spent the last part of his life in the Kew Asylum. So I found Kew Asylum records were available at PROV which was then at Laverton which was bloody hard to get to in those days because I don’t drive so it was a train and a bus and it took a long time and the bus seemed to come along sort of every other day so it was a long journey. But it was amazing to be able to look at those ledgers which had his record. In those days you used to actually get the card catalogue in town, there was a little office near Myers and there you’d get the reference and then you’d go out to PROV and then you’d present that and they’d give you the file.”

Now, things are a little easier. We have lots of records available online, some of which are detailed below. Physical records that haven’t been digitised are held in North Melbourne, or for some regional records, at one of our regional centres. All you have to do is place an order online and go in the next day to view the records in person. (Unless the building is closed due to a pandemic!)

Inquests

Of all the records in our collection, Gideon says inquests are among the most valuable for writers. Inquest records relate to deaths that occurred when a person died suddenly, for instance if they were killed, died in prison or in an asylum, died by accident or drowned.

“Inquests are most fantastic, the most granular, the most tragic, the most historically insightful because the way in which people die is a fascinating way to explore how people lived.

“One of the longest, protracted investigation tasks I undertook was looking at abortion related deaths in Victoria dating back to the very earliest files and you got a fascinating insight into women’s health and into the folklore and mythology and customs around it because a lot of the ways in which women procured abortions was on the basis of information that they’d gotten from other women… And it could be anything. Women had ideas that if you went on the roller coaster at Luna Park, if you drank a solution from copper coins in a glass of water, if you used a piece of bark to dilate the cervix, you could procure a miscarriage. And these were things that they just picked up locally. They hadn’t been told them by doctors… and lots of women came to harm because of the way in which they had to ‘fix themselves up’ as they used to say.

“In one file I remember there was a case in Benalla I think in the 1950s where the woman concerned had obviously done it before and she administered a solution of soap by a bicycle pump and in the inquest file there was the actual valve of the bicycle pump they’d put into a plastic pocket.”

In addition to the rare piece of physical evidence, like the valve, many inquests also include testimonies from witnesses or doctors, photographs of crime and death scenes (with or without the deceased in frame) and you may discover more about the deceased’s situation, or setting, leading up to the time of death.

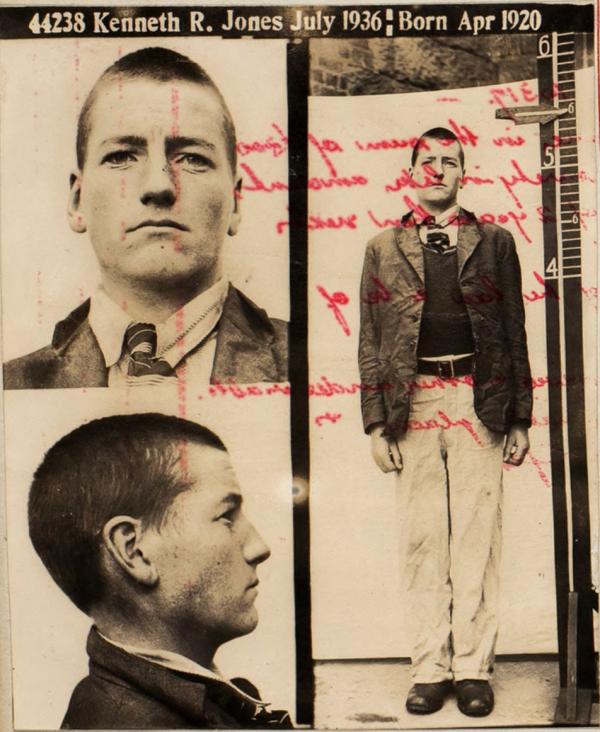

Another example is an inquest into a man who had once escaped Pentridge Prison, Kenneth Raymond Jones. He died in gaol in 1945 when a fight broke out, and so an inquest was held. The testimonies from the prison guards and other prisoners revealed what life for Kenneth was like in gaol. His relationships with the other inmates, how he and other prisoners would secretly make alcohol out of the fruit grown in the garden (this made headlines!), how he had few friends, and that at the time the fight broke out he was in the music room messing around with the gaol band.

If you were writing about a character spending time in gaol in the 1940s, reading an inquest like Kenneth's would be extremely useful. And heartbreaking. Inquests are certainly not for the fainthearted.

Some early inquests have been digitised and can be viewed online with physical files available to order and view in our North Melbourne reading room up to 1985. Be prepared when ordering physical files that some photos or evidence contained within could be quite confronting.

Some stories we have told using inquests include:

Police Correspondence, Prison Registers and Criminal Trial Briefs

If writing about crime, some of our most useful records include police correspondence, prison registers and trial briefs.

Police correspondence is organised in different ways depending on what year you are looking for. Records range from 1853 to 1935. Sometimes you might need to order multiple boxes to try and find the specific document you’re looking for – which may or may not exist! Gideon says no amount of trawling through records is wasted time.

“If you don’t know exactly where something is and you’ve got no choice but to inch your way through it, you discover so much along the way about the context in which circumstances happened or offences are committed. A good example was I was looking for a police report of a sexual assault in St Kilda in 1930 and it was mentioned in the police gazette but it didn’t give a precise date. So I had no choice but to go through box after box after box after box looking for this one particular piece of paper. And you got a fascinating sense of the social history of the time and what people went to the police for, how poor people were, how you lost a watch or you lost a tricycle or you lost in one case a bottle of tomato sauce, and you went to the police because you couldn’t afford to lose something like that. People did turn to police for every conceivable reason back then and it gave you a very strong sense of the material scarcity of depression Australia where every single material good mattered.”

Police correspondence files aren’t digitised, but that just makes the search more fun. Start by searching this page of our website (check the TIP box for records up to 1935), and once our Reading Room is open you can order and view these in North Melbourne.

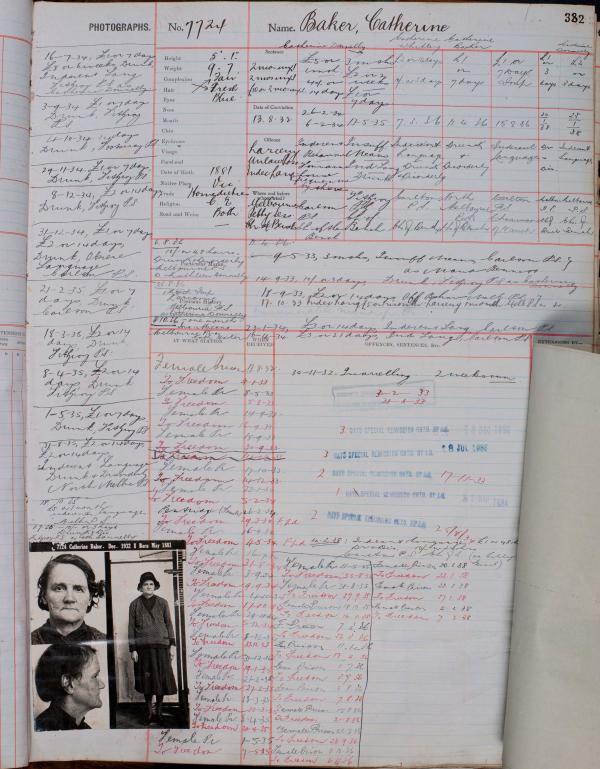

Two popular series that are digitised are our Registers of Male and Female Prisoners. These records were created when a criminal was sent to prison. Search a criminal in the search box here, and you can find their file which will contain a personal description, convictions, sentences, and if you’re lucky, a photo! Or multiple photos depending how many times they were in and out of prison over the years! Of course this series is helpful if writing about a particular Victorian criminal pre-1940. But the records can also be used in unexpected ways. If writing a fiction about 1930s Melbourne and needing names for your characters, why not trawl through and see what common names come up? Check the photos to see what people wore. You’d be surprised how smartly dressed some of these criminals were. You may also be interested in the kind of crimes people were being arrested for – for instance vagrancy, insufficient means, or arrested under the VD Act.

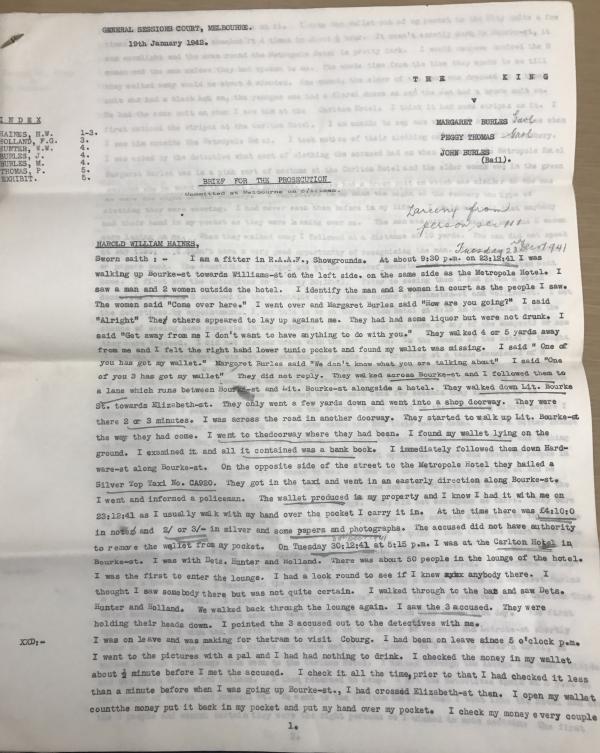

Criminal trial briefs haven’t been digitised but if you order and view them in our reading room, they are also a wealth of valuable information for writers. These records are the set of documents that make up the Crown Prosecutor’s case against an individual committed for trial in either the County or Supreme Court. The inquest deposition file forms part of this documentation, in most instances, where the charges relate to murder or manslaughter.

It goes without saying that if writing about a specific historic crime, the criminal trial brief for that crime will be useful. It’s the transcripts within these files that also prove interesting. Did you know some people called a matching skirt and blazer a “costume” in the 1940s? Neither did I until I saw it in a trial brief when a victim described the woman who robbed him as having worn a grey costume. There are so many words and phrases scattered throughout transcripts that can help you bring a time period to life when writing dialogue in your own work. And as Gideon says:

“There’s something very dramatic about transcript.”

Some example stories we have written using crime records include:

- Robbery Under Arms

- My Dear Husband

- Loss of Memory Man

- For the Excitement of the Game

- The Trouble with the McDonalds

Photographic collections

PROV holds a wide variety of photographic images showcasing the magnificent history of our State. The most popular are our Public Transport photographs. Not writing about public transport? Don’t scroll past just yet! These photographs, captured in most instances by Victorian Railways photographers, showcase more than just trains and trams. Using the 1930s as an example – if you were writing a historical scene set in 1930s Melbourne you could mine these photographs for streetscape inspiration, fashions, hairstyles, occupations, the sky really is the limit. Flick through some favourite examples are below:

Discover our photographic collections here.

Other, unexpected, record series

Sometimes you can discover inspiration and information in places you might not expect. While our collection includes all the crime files and inquests and photographs already described, it also includes maps, plans, divorce records, asylum records, wills, probates, and even some job and employee records, as Gideon discovered:

“Occasionally there are series that you find out about and you think why on earth did someone bother to collect that but thank god they did. When I was doing The Story of Jack Iverson, the Australian test cricketer, he was a real estate agent and I was out at PROV having a look at his inquest file and I was just idly looking in one of those big bulky books that have the different record series and I saw this thing called Index of Defunct Real Estate Agents. And I went really? Someone collected this? … So I found not only the file on Jack’s real estate practice, but his father’s real estate practice, and it had business testimonials by people who worked with him and their neighbours. So you got this fantastic intimate glimpse into his character by people who worked in his milieu, had lived alongside him, had known his wife and his kids, and that was just a complete accident. A random opening of a page in a big book.

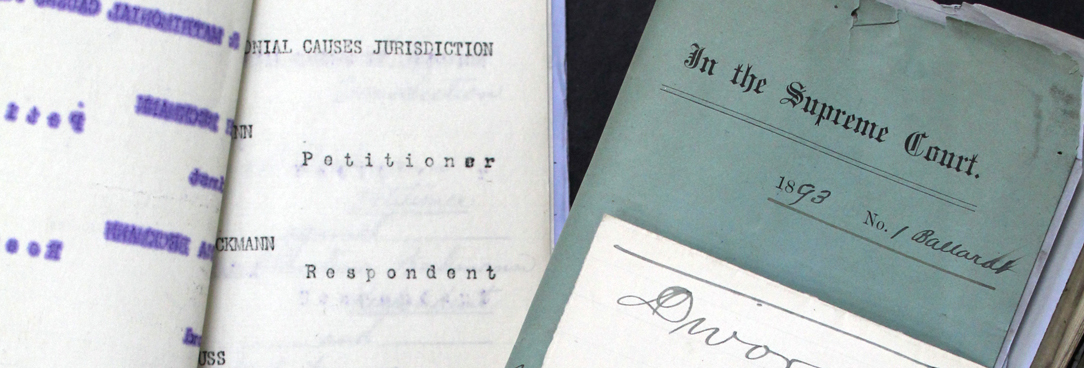

“The other thing I’ve used are school files when I was researching Molly Dean’s teaching career, for A Scandal in Bohemia, and they were interesting. They’re very undifferentiated, and you never know what you’re going to get when you open any box, but some of them were really informative. And there are records for teachers, over your career. An inspector would come and see you teach every year and they’d give you a report. There were building files for the schools concerned where she taught at so I learned a lot about the physical infrastructure that she was working in. The other one is divorces. I haven’t used a lot of divorce files but they are really fascinating. I looked at the divorce of Colin Colahan and his wife Vi, the Australian painter, and he was an absolute rogue. The file of Gilbert and Chica Boileau and she had about three different lovers and the husband had put the detectives on her tail and followed her to various assignations, because it was so much about fault or infidelity or desertion required quite a high bar of proof in those days.”

Many of the types of records Gideon mentions can be found by starting on our Family History Search page here. A new tool we’ve also developed to display our digitised maps and plans is the PROV Map Warper tool. The tool features historic maps and plans from our collection which can be placed over current day coordinates so you can easily see differences over time. Then there's public building files which can show you how the buildings you’re writing about looked, particularly where photos may not be available or may not give a complete picture of the layout needed for your story.

New to archival research?

When researching our collection you need to think about what ways in which your subject or character may have interacted with government and what files the government may have kept in relation to that interaction, or that could help you tell your story. If you’re new here you may like to check out our Where to Start page.

Once you delve in, we hope you agree, that archives can provide so much inspiration for writing of any kind, from any time period. Gideon Haigh says:

“You learn so much about the conditions in which people lived. You learn so much about how big households were, how many people there were in a family, the sort of occupations that people had, the way in which they earned money on the side, the culture of the police at the time. I’ve used public records, alongside records from other institutions, such as the police, and you get a pretty strong sense of the way in which the police related to the legal profession, related to the public service, related to the Attorney General. One thing that you get a very strong sense of how small people’s circles were. How the same names kind of crop up in the same sort of cases again and again.”

So, what names, dates or places will you be searching?

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples