Last updated:

‘Tracing ancestral voices’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 21, 2023-24. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Kendrea Rhodes.

‘Tracing ancestral voices’ outlines a genealogical research journey involving memory, emotion, history and archival research. It demonstrates the reclamation of lost ancestors and their stories, covering the inevitable highs and lows of archival research. Resources employed during this research include the archives, databases and websites of Public Record Office Victoria, Birth Deaths and Marriages Victoria, the Department of Health and Human Services, and other government resources.

At the centre of this research are the author’s grandfather, Charles William Stott/Hicks, and great-grandmother, Ethel Blanche Hicks. Just days before passing away in 2008, Charles had whispered into the ear of his great-grandson: ‘You can’t choose your family.’ Those curious words were the inspiration for the author’s family history inquiries. The research started with birth and death certificates, eventually leading to state ward records. These revealed that, in 1924, Charles, aged five, and his siblings, had been made wards of the state of Victoria. To understand possible causes for this, numerous public document collections and institutional records were analysed and cross-referenced to show how details and discrepancies can be used to support hypotheses and speculation.

Reader warning: the terms ‘mentally deficient’ and ‘illegitimate’, which some may find offensive, are used in some of the records. They are used here to offer insight into the historical context of the era.

My family history research journey started with a whisper from my grandfather, just days before he passed away. His words seeded emotion, interest and purpose, eventually growing into solid questions like: What happened to his birth family? Why did he become a ward of the state?

Family history research has the potential to grow rapidly from a seed of an idea into a forest of information, generating many avenues for exploration. My foray began online with genealogy databases, like Ancestry.com, that provided instant overviews of information and resources. I saw myself as an archival archaeologist hunting for the material remains of my ancestors to ask them why they did what they did, unaware that I teetered on the slippery rim of my own contextual biases, expectations and emotions. Although Ancestry.com produced fast results, I required specific and detailed archival research and support. For that I turned to Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), Births Deaths and Marriages Victoria (BDMV), the National Archives of Australia, TROVE, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), and government websites such as Find & Connect. After headbutting several archival boundaries along the way, I learned that archival records can only tell you so much. The rest is up to you.

Charles William, my grandfather

In 1924, at the age of five, Charles William Hicks became a ward of the state of Victoria and rapidly lost touch with his birth family. For the remainder of his childhood, his homelife cycled through places like the Royal Park Depot and various care homes throughout Melbourne.[1] As an adult, he went by the surname of his last foster family and did not personally seek out his birth family.

In 2008, my 89-year-old grandfather, Charles William Stott, lay in his hospital bed chatting intently to my five-year-old son. Charles had had an extraordinary life, and he was enjoying himself, surrounded by his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

At one point, Charles whispered into my son’s ear: ‘You can’t choose your family.’ This poignant moment, just days before my grandfather’s passing, proved to be the catalyst of many years of research. My grandfather’s comment propelled me through copious archives and family memories and, eventually, to tertiary education. Back then, though, I knew none of that. I just appreciated a beautiful moment of genealogical embodiment between a great-grandfather and his great-grandson.

‘You can’t choose your family’

The question arose as to which family my grandfather was alluding to—his birth family, boarding-out families, foster family or us? It took a while to decide, but in 2015 I began historical research into Charles’s birth family. I started with his parents, Ethel and James Hicks, because, after all, their actions affected all of Charles’s subsequent families. I had in my possession something that I thought was a pretty good lead—a copy of Charles’s birth certificate that he obtained in 1990.[2] In 2015, it felt like a golden beacon of light glowing with significance. I devoured the details ravenously: Charles’s birthdate, address in Mildura, the names and ages of his three older siblings, and details about his parents—their names, marriage date, occupations, ages and birthplaces.

I had not thought about my grandfather’s past until that poignant moment in 2008, but his daughter, my aunt, had often thought about his birth family. In the 1980s, my aunt made numerous unsuccessful attempts to find them and had almost given up when she came across a missing person advertisement in Melbourne’s Sun newspaper. The person who placed the advertisement was Mary Hicks, Charles’s older sister. After a few phone calls, a Hicks family reunion was organised to gather the few remaining siblings and their families together.

The reunion had been fun for us kids, belting about a lush green park in Daylesford, eating ice-cream, and cheese and vegemite sandwiches. But it was not enjoyed by all. From that modest gathering my grandfather had discovered his surname, birthdate, birthplace, his parents’ names (James and Ethel Hicks), that his father had disappeared, and that his mother had retrieved his sisters from state care, but not him or his brother. An upsetting revelation. After the reunion, Charles’s siblings still felt like strangers to him and he lost contact with them, deliberately this time. Sometimes you can choose your family.

Traces: birth and death certificates

A decade after the Hicks siblings’ reunion, my grandfather applied for his birth certificate with help from my aunt. Curiously, the certificate listed his parents as James William Hicks and Blanche Rosina Hicks.[3] While I favoured the authority of the birth certificate, something niggled regarding the name Ethel, mentioned at the Hicks family reunion. Charles’s sisters knew their mother in later life, so they would not get her name wrong. I began wondering whether Blanche and Ethel were two different people.

To discover Charles’s mother’s identity, I used other information from his birth certificate as search parameters on the website of BDMV. For example, his mother’s maiden name (Rodier), birthplace (Yarragon), and age (34 years in 1918, therefore born around 1885). These details produced both birth and death certificates that supported the name of Ethel Blanche[4] and, in combination, they helped to confirm that Ethel Blanche was also Blanche Rosina (shown later in this essay). In addition, Ethel’s death certificate contained important biographical information about her life and death, such as the names of her children with James Hicks, and the fact that she had had three husbands.

While the birth and death certificates were useful for plotting milestone events, the relative futility of searching for motivations and emotions within the storage systems of institutional archives and public recordkeeping soon became apparent. It dawned on me that the certificates I had did not contain Charles’s or Ethel’s words. They contained commonly recorded information about them in the words of others. I had revelled in the elation of hitting some kind of jackpot with Ethel’s death certificate—ironically, it was as if I had found a living, breathing person who was about to reveal her motivations and feelings. But these records were never going to do that.

Stephen B Hatton says that ‘documents are traces that need to be understood as such and only then used to interpret the past’.[5] I mulled on that in conjunction with Judith Butler’s thoughts on traces—that they might be ‘at once lost and found’[6]—and, eventually, understanding crystalised. I had not found my great-grandmother. Nor had I found her words or thoughts. What I had discovered were traces. And gaps between the details of each trace would require interpretation and speculation. With this realisation, I felt I had lost her again.

Public Record Office Victoria

My research needed to go deeper. More ancestral traces, more documents, more ways to interpret their actions. So, I turned to PROV. It started as a digital relationship, perusing collections and information on the website. I familiarised myself with privacy laws and PROV processes and record categorisations, such as agencies and record series. As I altered my expectations from looking for answers to slowing down and following traces and clues, the value of the PROV collections increased exponentially: there is a distinct advantage to waiting, as, in time, more and more public records become open, digitised and accessible to the patient researcher.

My first online enquiry with PROV drew a succinct, informative and non-judgemental response (no mention of my overzealous inclusion of absolutely everything I knew).[7] In a nutshell I asked for information regarding the whereabouts of Charles’s biological family between 1923 and 1925. PROV staff informed me that Charles’s care-leaver documents were non-government institutional records and not necessarily held at PROV; they suggested that I visit the Find & Connect website. They also confirmed that records about Charles’s parents, Ethel and James Hicks, were held at PROV.

Court, gaol and Find & Connect

PROV reading room, North Melbourne

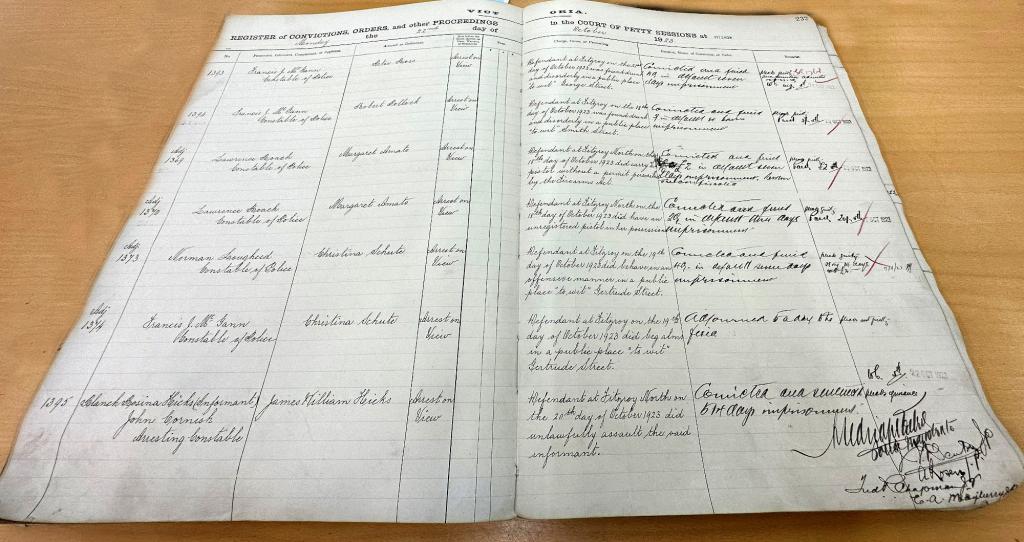

The records of the Fitzroy Court revealed that James had been gaoled for 14 days for abusing Ethel in October 1923 (Figure 1).[8] These records provided names, dates and places that I used to search TROVE, an online database containing ‘collections from Australian libraries, universities, museums, galleries and archives’.[9] TROVE returned fruitful results on the incident, which was reported in two Melbourne newspapers, the Argus and the Age.[10] Besides providing details of court proceedings and James’s sentencing, Ethel was also reported to have said that James ‘was a good man when sober’.[11]

Figure 1: Fitzroy Court records pertaining to James William Hicks’s sentencing, 20 October 1923, PROV, VPRS 6059/P0001/1395. The bottom line, number 1395, is Hicks’s record.

From the court records and newspaper reports I began speculating that James’s relationship with alcohol was problematic and might have caused issues for the family, possibly leading to the commitment of the children to the state. This kind of information was exactly what I was looking for, so why did my speculation feel empty?

I decided on a new direction and contacted Find & Connect in search of Charles’s state ward records. Find & Connect, as its website states, provides ‘history & information about Australian orphanages, children’s Homes and other institutions’.[12] The website was a boon to my family history research, offering many new resources, quality articles, photographs and historic details. After investigations, the Find & Connect staff informed me that Charles’s state ward records still existed; however, to read them, I would have to apply to the government department that created them—DHHS.[13]

Department of Health and Human Services

As might be expected, applying to a government department for family records requires accuracy, diligence and patience. After thorough identity checks and information exchanges with DHHS over a few months, I received photocopies of all the Hicks children’s state ward records in the post (Figure 2). Redacted versions of Charles’s siblings’ records were included because their contents revealed general family details that were not on Charles’s record.

Figure 2: 1924 state ward registry entry for my grandfather, Charles William Hicks, PROV, VPRS 4527, 54539.

Upon opening the long-awaited package, I took the time to appreciate the glorious green pages, flowing cursive script, meticulous columns and index markings on the 90-year-old records. The physical copies I held in my hands represented a pinnacle moment, but it was not an end-goal achievement—not with my newly adjusted expectations. The state ward records enabled the piecing together of fragments, traces and the shrinking of silences. For example, I discovered that, for a period of eight years from the age of five, Charles had moved frequently in and out of homes and institutions across Melbourne in suburbs like Collingwood, Preston, Clifton Hill, Ringwood and Royal Park. He eventually settled into a more permanent foster home at the age of 13, where he stayed until adulthood. In light of this information, it seems reasonable for Charles to have taken this foster family’s surname, as they represented the only stable home he had known in his youth.

Mary Florence and state ward records

Figure 3 is an excerpt from the state ward registry entry of my grandfather’s sister, Mary Florence Hicks. Mary’s record contains information about their parents that did not appear on the other Hicks children’s records, which is why it is included in this analysis. There are three points of interest on Mary’s record:

- ‘Father: James William Hicks, labourer, has been sentenced to imprisonment for assaulting his wife.’

- ‘Mother: Blanche Rosina Christensen, now Hicks, is mentally deficient, came from Mildura with children.’

- ‘Child: is apparently illegitimate but the other five children born after parents’ marriage’.

Figure 3: 1924 state ward registry entry for Mary Florence Hicks, PROV, VPRS 4527, 54536.

The first point is corroborated by the Fitzroy Court documents (see Figure 1). Coupled with a further comment on Mary’s record that James had ‘cleared out from his wife and children’,[14] this point adds weight to speculation of poverty and housing issues for the family. The second point contains several pertinent details. First, it provides a link to Ethel’s death certificate through the name Christensen. Second, the mention of Mildura provides a link to Charles’s birth certificate, as his place of birth. Third, it describes Ethel as mentally deficient, a recurring description in other sections of the Hicks children’s state ward registry entries. Historian Naomi Parry raises an important point for consideration in relation to the term ‘mental deficiency’ and its use in the first half of the twentieth century in Australia:

mental deficiency was used … [to describe people with an] intellectual disability, social problems, criminality and even unconventional sexual behaviour, such as sex before marriage. It should not be assumed that people labelled ‘mentally deficient’ were intellectually or otherwise disabled—some ‘mental defectives’ were noted to be ‘high grade’, or of normal intelligence, but behaved in ways authorities could not accept.[15]

The third point highlights Mary’s illegitimacy, which, obviously, was relevant to the state record keepers despite her parents’ subsequent marriage. Why? Was Mary’s ‘illegitimacy’ a sign of Ethel’s flawed character and unacceptable behaviour? Did it signal Ethel’s and James’s flawed values? Considering the likely values of the time, in which, as Colin James puts it, ‘legitimacy [was promoted] as the proper and “natural” status’,[16] illegitimacy could reasonably be considered improper and unnatural. Thus, having an illegitimate child could have resulted in Ethel being labelled as mentally deficient.

Handwritten voices

When I first read my ancestors’ handwritten state ward records,[17] I made instant judgements from my own historical context. I assumed that statements like ‘illegitimacy’ and ‘mental deficiency’ were subjective opinions because they were handwritten. In the same way, I presumed that Charles’s birth certificate was accurate because it was typed, having been reproduced in 1990.[18] I had applied a subconscious bias that equated officialdom and accuracy to the familiar format of a typed document. Nevertheless, value teemed within these faulty assumptions because they stimulated questions, further research and new knowledge.

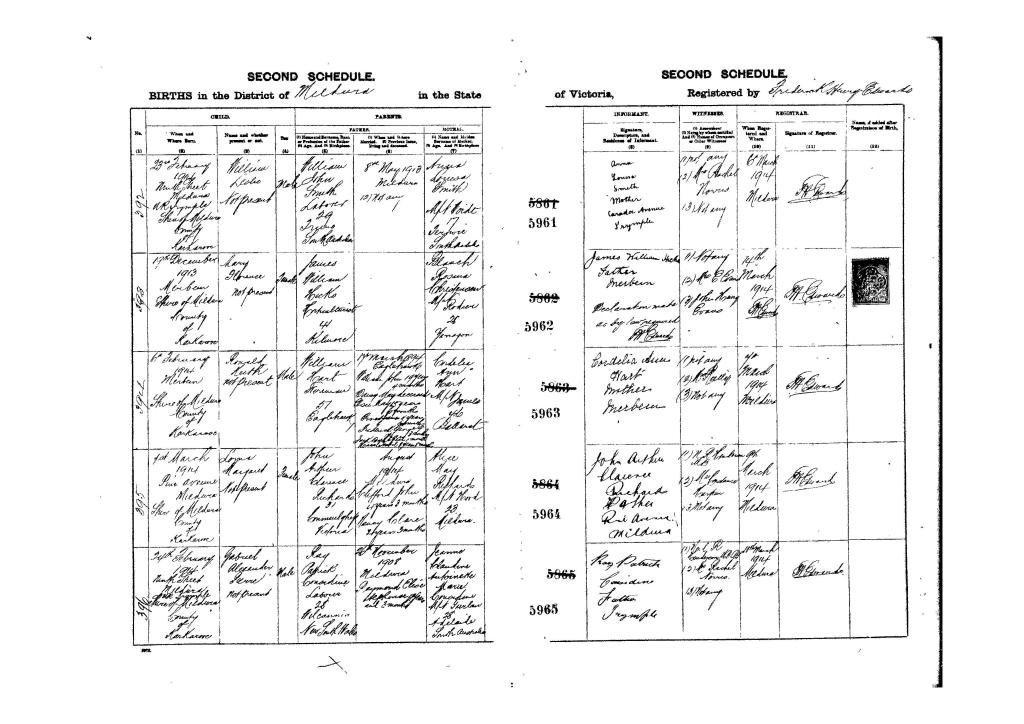

It became clear that the veracity of the documents in my possession required crosschecking to test Mary’s recorded status as illegitimate. I retrieved Mary’s birth certificate and compared her birthdate—19 December 1913[19]—to the date of Ethel and James’s marriage as recorded on Charles’s birth certificate—11 April 1912.[20] According to this easy comparison, Mary was born after her parent’s marriage, so why would the state record keepers describe her, aged 10, as illegitimate? I almost dismissed the comment as a mistake, but eventually took the path of due diligence and pursued other source documents. It was the handwritten records that inspired my directional pivot—there’s something sublime about handwriting, hinting at a flow of temporal human connections, of words captured the moment they are spoken. I realised that those handwritten records may be the closest I will ever get to hearing my ancestors’ voices.

Identity, legitimacy and divorce

Further research was required to determine Ethel’s identity and Mary’s legitimacy, so I sourced and compared 13 documents: 1906, Christensen marriage (BDMV); 1913, Christensen divorce (PROV); 1914, Hicks marriage (BDMV); 1913 and 1918, Mary’s and Charles’s birth certificates (BDMV) (see Figure 4); seven Hicks children’s state ward registry records from 1924 and 1926 (DHHS, now PROV); and Ethel’s 1960 death certificate (BDMV).[21]

Figure 4: Birth certificate for Mary Florence Hicks, BDMV, 5962/1913. Second line, numbered 393 on the left, note the blank space under ‘When and where married’.

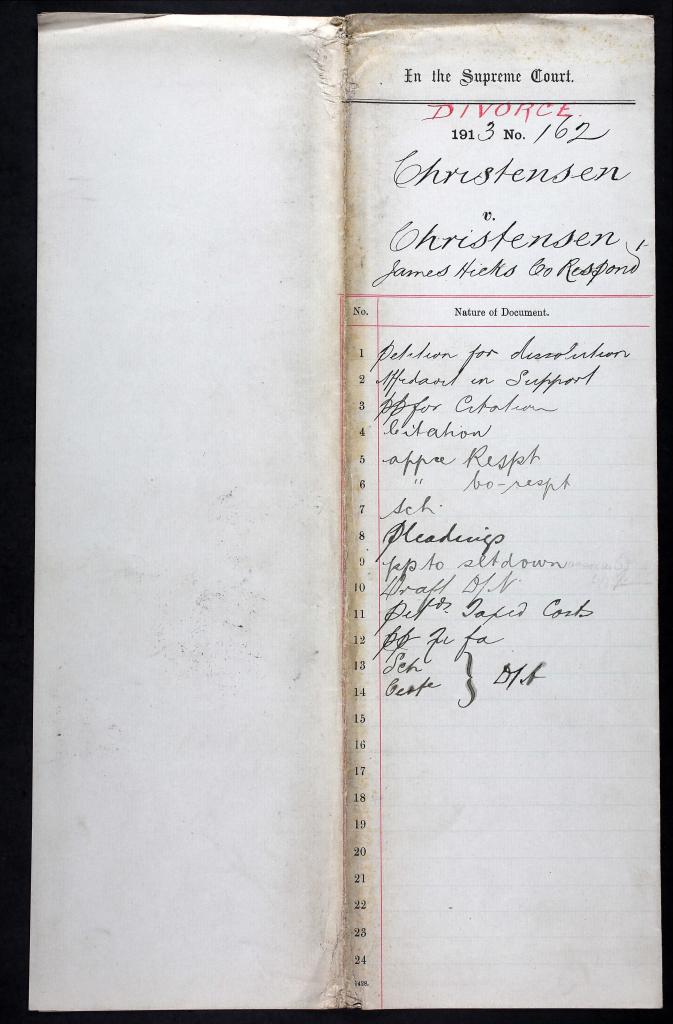

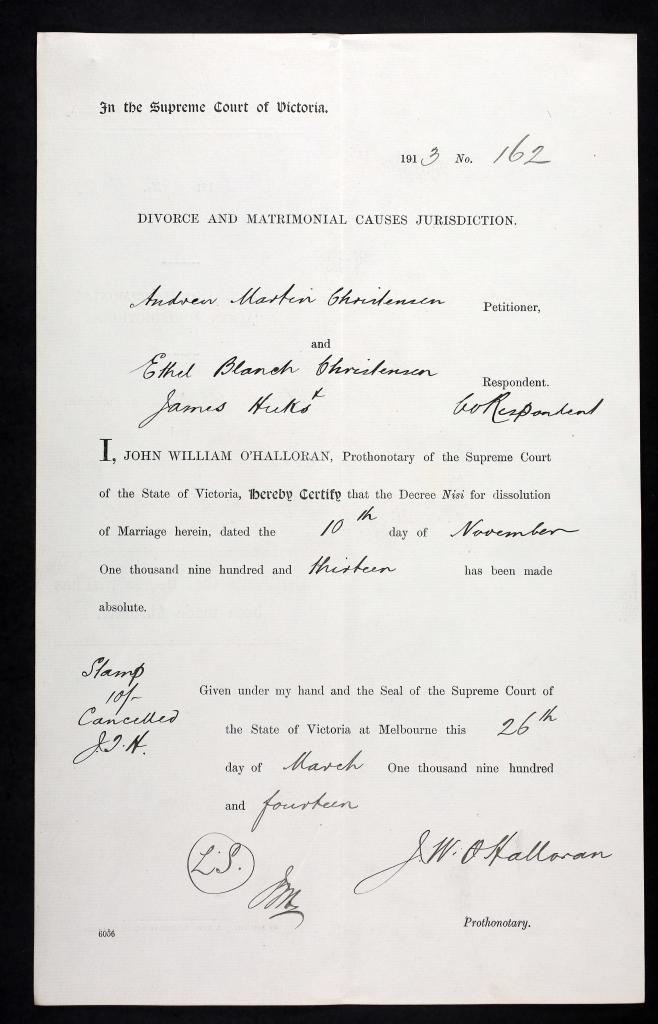

Ethel’s death certificate indicated she had been married prior to her marriage to Hicks, so I searched for her previous marriage, attempting to align dates. What I found answered other questions about her identity. Ethel Blanch Rodier of Yarragon married Andrew Martin Christensen in Melbourne on 25 September 1906.[22] Seven years later, in July 1913, divorce documents were filed in the Supreme Court of Victoria by Andrew Christensen, accusing Ethel of cohabiting with James Hicks (see Figures 5 and 6).[23] The divorce documents referred to Ethel Blanche Christensen and Blanche Christensen as the same person. Together with the information from Ethel’s death certificate about her children and marriages, and Charles’s birth certificate listing his mother as 34-year-old Blanche Rosina Hicks, née Rodier,[24] it is clear that Ethel and Blanche were the same person.

Figure 5: Divorce, Christensen v. Christensen & James Hicks, co-respond., PROV, VPRS 283, 162/1913.

Figure 6: Divorce decree absolute, Christensen v. Christensen & James Hicks, co-respond., PROV, VPRS 283, 162/1913.

The Christensen divorce papers provided enough detail to source Ethel and James’s official marriage certificate from BDMV, enabling confirmation of their marriage date. The decree nisi of the Christensen divorce became absolute in March 1914 and Ethel and James’s marriage certificate was dated one month later, in April 1914.[25] However, Mary’s official birth certificate was dated 19 December 1913, four months prior to her parents’ marriage.[26] In addition, a column on Mary’s birth certificate concerning parentage, titled ‘where and when married’, was left blank (see Figure 4). If I had only looked at Mary’s birth certificate, I may well have dismissed the omission of her parent’s marriage as human error and settled on the marriage date of 11 April 1912, listed erroneously on Charles’s birth certificate. But, in the company of other documents, the omission on Mary’s birth certificate became a clue hinting at misdirection.

From my analysis of these documents, I concluded that Mary was born before her parents’ marriage and would, therefore, have been considered ‘illegitimate’ in that era. In my naivety, I assumed the status of illegitimacy would have diminished after her parent’s marriage; however, the stigma of illegitimacy punched right through that first decade of Mary’s life with all its weight, to be recorded in perpetuity on her state ward registry record in 1924. Mary’s illegitimacy suggests a certain permanence to the title, maybe even a punishment bestowed upon birth and a warning for future ‘unwed parents’.[27] In the context of the times, these are plausible grounds for Ethel and James to inform the record keepers of a false marriage date of 1912 instead of 1914 when registering Charles’s birth. This action may have eased the stigma of illegitimacy that not only labelled Mary and Ethel but washed over them all.

Informants

My incredulity grew over concerns about inaccuracies on archived documents: how could a false marriage date be recorded on official records? Then I remembered Kath Ensor’s cautions in her Provenance article entitled ‘Family and social history in archives and beyond’.[28] In essence, once documents are compared, cross-referencing can flush out frequent errors like omissions, misspelled names, wrong dates and incorrect statements.[29] Ensor says that, although Victoria has had a ‘system of civil registration’ since 1853, ‘the information recorded is only what the informant knew and in some cases is very scant or incorrect’.[30] Therefore, it makes sense that the knowledge, motivations and literacy levels of informants, and the record keepers of the time, could have influenced the accuracy of the records that I was relying upon. The informants in my case were my great-grandparents, James and Ethel, and, given the social norms of the era concerning adultery and illegitimacy, it seems reasonable that they might have wanted to hide those details.

Put them on the state

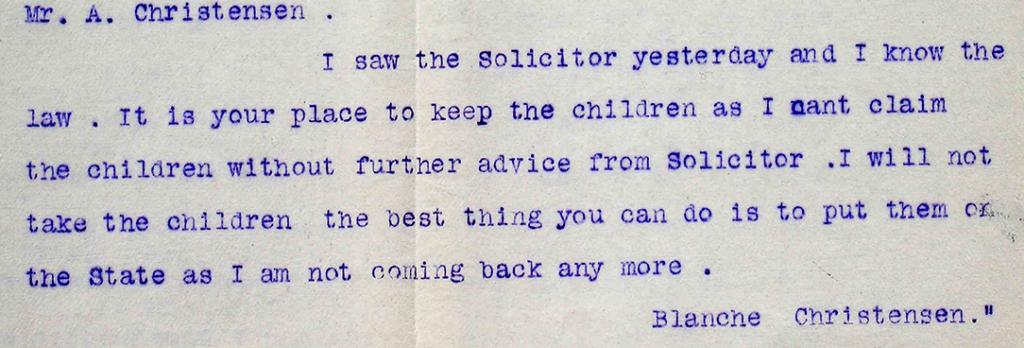

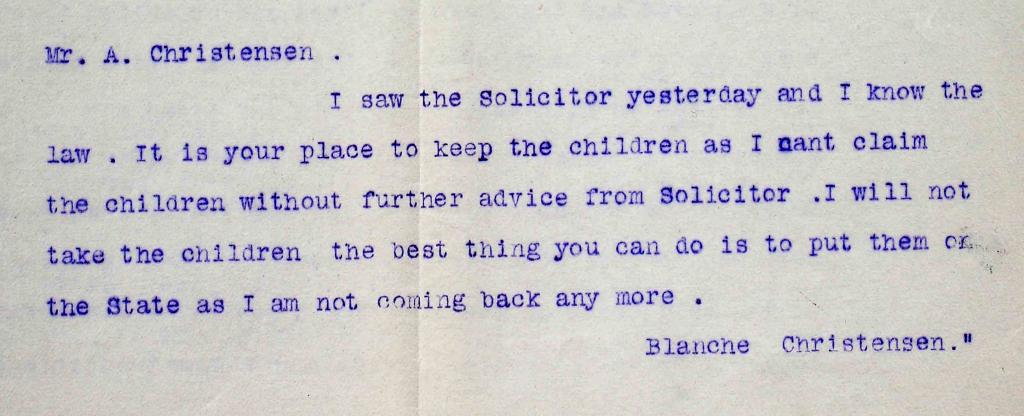

The divorce documents for Ethel and her first husband, Andrew Christensen, contained interesting details, highlighting far more of Ethel’s character than I expected.[31] While much of the discussion is beyond the scope of this essay, I would like to touch on one statement concerning the three children that Ethel and Andrew had together.

Figure 7 is a copy of a note by Ethel that was used as evidence in Andrew’s claim of irreconcilable differences. Ethel states: ‘I will not take the children the best thing you can do is to put them on the State as I am not coming back any more [sic].’[32] A number of scenarios present themselves as possible explanations for this line: for example, it could have been written on the advice of Ethel’s solicitor; putting children ‘on the State’ may have been common for people in Ethel’s situation; it may have been what Ethel wanted—to be separated from her children as well as Andrew. In any case, it suggests that putting children ‘on the State’ was not an unfamiliar route for Ethel and James to take.

Figure 7: Ethel’s note (signed Blanche Christensen) to Andrew regarding their children, PROV, VPRS 283, 162/1913.

What did I learn?

My initial reason for approaching PROV, BDMV, DHHS, Find & Connect and other sources was to discover why my great-grandparents had abandoned my grandfather. The unravelling results of my research added layers of complexity to this initial question and showed me that there were no straightforward answers. So I began to speculate, using public and institutional records as guides. As the number of documents in my possession increased, I was able to refine my speculative thinking and produce evidence to support possibilities and timelines. I found out that:

- My great-grandmother’s name was Ethel Blanche Hicks and she was married three times; my great-grandfather was her second husband.

- My great-grandfather, James William Hicks, was jailed for violence under the influence of alcohol and was an unreliable provider and caregiver, likely contributing to the family’s separation.

- Six of Ethel and James’s children were committed as wards of the state of Victoria on 16 June 1924, and one of those children was my grandfather, Charles William Hicks.

- Charles’s sister Mary Florence Hicks was born before her parents were married and while Ethel was still married to Andrew Christensen.

- Before her children with Hicks came along, Ethel had suggested putting the children of her previous marriage ‘on the State’,[33] presumably making them wards of the state of Victoria.

- Ethel likely ran afoul of social norms in the era regarding sex before marriage and adultery, which may have led to her ‘mental deficiency’ label.

Using these details, I have imagined, speculated and fictionalised the events and emotions[34] that led to the abandonment of my grandfather. At face value, resorting to speculation may seem like admitting to failure; however, it is exactly the opposite. It was not that long ago that my grandfather seemed lost to me—and my great-grandparents were neither lost nor found. Now, by contrast, Charles, Ethel and James are ethereal traces on my cognitive pathways, blossoming from public documents: birth certificates, ward records, marriage certificates, divorce papers, death certificates. Each milestone is a red-topped pin on a life cycle roadmap, connected by strings of speculation. My grandfather lives on in my memory, larger than ever before, while my great-grandparents’ newly birthed presence blooms in the dreamy thickets of my imagination.

Conclusion: good gaps and boundaries

Charles William Stott (Hicks) died on Anzac Day in 2008, surrounded by the family he chose. While his life and death have been catalysts for my work, my family history research is not about origins anymore. It is about processes, emotions, mystery and the research journey. I’ve joined a few dots, located people and places, and generated extra gaps: smaller gaps between many more records; acceptable gaps that sit naturally within the boundaries of archival research; natural silences that we all take with us when we go; emotions, thoughts, reasoning, dreams and memories. I was never going to find definitive answers to my questions, but now the nuanced gaps teem with possibility rather than impossibility.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VA 1467 Children’s Welfare Department, VPRS 4527, Ward Register (known as Children’s Registers 1864–1887), 54539, Hicks, Charles William, 1924, https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VPRS4527#.

[2] Victoria, birth certificate, Charles William Stott, 80549/1990, copy in possession of author.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Victoria, birth certificate, Ethel Blanche Rodier, 29931/1885; Victoria, death certificate, Ethel Blanche Harris, 11193/1960.

[5] Stephen B Hatton, ‘Genealogy’s assumptions about written records and originality’, Genealogy, vol. 5, no., 1, 2021, p 3, doi:10.3390/genealogy5010021.

[6] JP Butler, ‘Introduction’, in J Derrida & G Spivak (trans.), Of grammatology, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2016, p. x.

[7] PROV Access Services Team, personal communication, 10 April 2015.

[8] PROV, VA 2303 Court of Petty Sessions/Magistrates’ Court, VPRS 6059/P0001/1395, Police/Arrest Registers (Melbourne), 28 January 1923 to 19 November 1923, https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/86B19B7A-F4E7-11E9-AE98-793A85D45000#.

[9] TROVE, ‘About’, available at https://trove.nla.gov.au/about, accessed 20 August 2023.

[10] ‘Afraid of drunken husband’, Argus (Melbourne), 23 October 1923, p. 13; ‘An affrighted family’, Age (Melbourne), 23 October 1923, p. 11.

[11] ‘An affrighted family’.

[12] Find & Connect, homepage, available at https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/, accessed 22 January 2024.

[13] The records have since moved to PROV: VPRS 4527, State Ward Register.

[14] PROV, VPRS 4527, 54536.

[15] Naomi Parry, ‘Mental deficiency (1905–1960)’, available at https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE00992b.htm, accessed 13 April 2023.

[16] Colin James, ‘Winners and losers: the father factor in Australian child custody law in the 20th century’, Legal History, vol. 10, nos 1–2, 2006, pp. 207–238, doi:10.3316/ielapa.335597852544605.

[17] PROV, VPRS 4527, 54536–541, 1924.

[18] Victoria, birth certificate, Charles William Stott.

[19] Victoria, birth certificate, Mary Florence Hicks, 5962/1913.

[20] Victoria, birth certificate, Charles William Stott.

[21] PROV, VA 2549 Supreme Court of Victoria, VPRS 283, Divorce Case Files 1860–1940, (Christensen v. Christensen) 162/1913; PROV, VPRS 4527, 54536–541, 1924; PROV, VPRS 4527 56263 (Kenneth John Hicks), 1926; Victoria, birth certificate, Charles William Stott; Victoria, birth certificate, Mary Florence Hicks; Victoria, death certificate, Ethel Blanche Harris; Victoria, marriage certificate, Blanche Rosina Christensen and James William Hicks, 214/4795 1914; Victoria, marriage certificate, Ethel Blanche Rodier and Andrew Martin Christensen, 984/6216 1906.

[22] Victoria, marriage certificate, Ethel Blanche Rodier and Andrew Martin Christensen.

[23] PROV, VPRS 283, (Christensen) 162/1913.

[24] Victoria, death certificate, Ethel Blanche Harris; Victoria, birth certificate, Charles William Stott.

[25] Victoria, marriage certificate, Blanche Rosina Christensen and James William Hicks.

[26] Victoria, birth certificate, Mary Florence Hicks.

[27] James, ‘Winners and losers, p. 212.

[28] Kath Ensor, ‘Family and social history in archives and beyond’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 9, 2010, pp. 16–26, https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2010/family-and-social-history-archives-and-beyond, accessed 13 April 2023.

[29] Ibid., p. 17.

[30] Ibid.

[31] PROV, VPRS 283 (Christensen) 162/1913.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] KL Rhodes, ‘“You can’t choose your family”: a fictocritical palimpsest of family stories’, honours thesis, Flinders University, 2022.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples