Last updated:

‘Discovering an archive’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 20, 2022. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lucinda Horrocks.

In turn of the twentieth-century Melbourne, a pioneering network of women at the Mission to Seafarers called the Ladies Harbour Lights Guild (LHLG) supported sailors who risked their lives at sea. The deeds of this remarkable group of women were almost forgotten until 2007, when a set of dusty old boxes were discovered stored under the mission's theatre in the 90-year-old state heritage-listed building at 717 Flinders Street. The boxes held an archive filled with documents and photographs related to the activities of the LHLG from its foundation in 1906 to its demise in the 1960s. In recent years, a dedicated team of volunteers and staff at the mission has been gradually digitising, identifying and cataloguing the guild records. In 2018 and 2019 I had the opportunity to observe the work of the archive team while producing a short documentary about the LHLG. This article answers the question: what happens next after an archive of rare significance is discovered? Here I document some observations of the mission, its ongoing work, and the remarkable building and its connection to a hundred-year-old story of shipping, sea work and a community of volunteer women, as revealed through the slow and fascinating work of exploring an archive.

Figure 1: Mission to Seafarers Victoria today. Still from the film Harbour Lights, 2020. Courtesy of Wind & Sky Productions.

Treasure trove[1]

In 2007, the Mission to Seafarers, that curious-looking building with the dome and the bell tower at the Docklands end of Flinders Street, discovered 10,000 rare archival documents stored beneath a stage. The 90-year-old state heritage–listed building had needed a spring clean, Andrea Fleming, the Mission to Seafarers chief executive, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Broken computers, desks and old books were piled into a skip, and then ‘right down at the back of the stage in the main hall were all of these dusty old boxes, we pulled those dusty old boxes out—and they revealed an archive’.[2]

It is easy to understand why the story made the news. The discovery of long-forgotten records hidden under a stage has irresistable appeal. It feels like the beginning of an adventure, the type where a historical mystery inevitably leads to a treasure hunt with maybe a few murders plus a bit of romance along the way. But what happens next when a real life archive is discovered?

I had a chance to find out in 2018 and 2019 when the mission invited my film company to make a documentary about the building’s connection to World War I (WWI) and a group of women called the Ladies Harbour Lights Guild (LHLG). The topic of the documentary related to the discoveries a committed group of volunteers and staff were making as they worked through the mission archive.

The spoiler (which will be no surprise to anyone who has ever actually worked with archives) is that ‘what happens next’ is complex, time-consuming and unromantic. But there is a kind of adventure to it as well. In its own way, an archive really can lead to treasure.

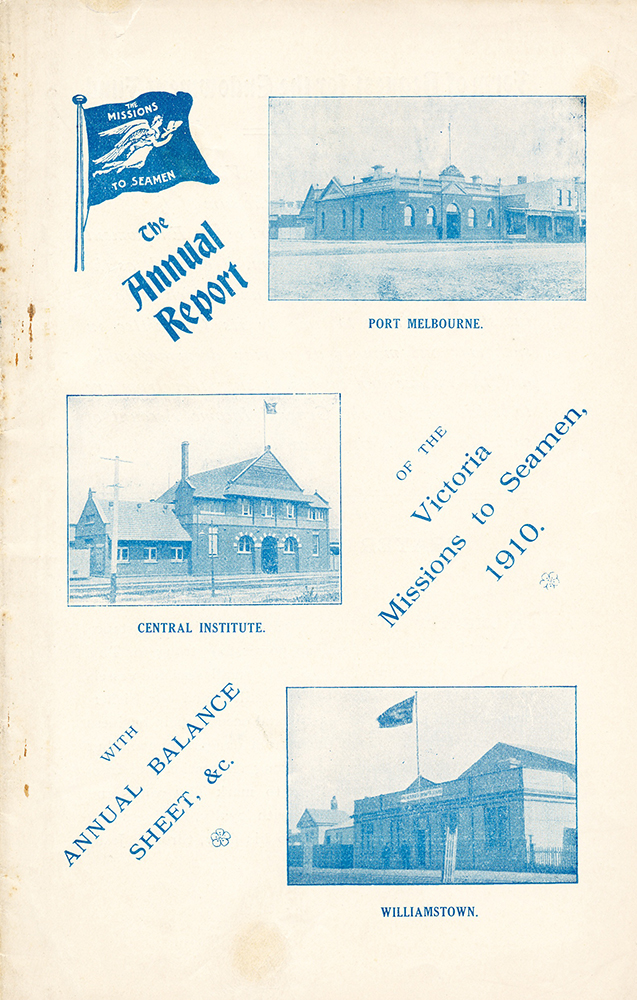

Figure 2: Cover of the Missions to Seamen 1910 Annual Report with photographs of the Port Melbourne, Melbourne (Siddeley Street) and Williamstown institutes. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

What is the Mission to Seafarers?

The Mission to Seafarers is an Anglican-aligned organisation with international links that has provided welfare to seafarers since the early days of Melbourne’s ports.[3] The Melbourne mission is situated on the busy south-western edge of the CBD where multi-lane Wurundjeri Way snakes traffic onto the West Gate Freeway. When it first opened in 1917 its address, ‘Australian Wharf’ (it is now more prosaically addressed as 717 Flinders Street ), made it part of Melbourne’s commercial shipping precinct on the Yarra River.[4] Today it gets a little lost amid the high-rise developments, cafes, direct fashion outlets, five-star hotels and convention centre, but it was once a prominent landmark in a lively working area of ships, wharves, cargoes, pubs, markets and industry. Thousands of annual visiting sailors would have recognised it as one of many missions around the world offering services, religion and respite to seamen.[5]

In the nineteenth century, concerns over the poverty sailors often lived in, the exploitation they were vulnerable to and worries over their spiritual welfare led to the emergence of a number of philanthropic and religious organisations offering welfare and religious services to sailors.[6] The first such mission in Victoria was a floating church—a ship hulk anchored in Hobson’s Bay—in 1857.[7] Shore-based missions were subsequently built at Port Melbourne and Williamstown. Like the floating church, these were founded close to where the ships anchored. Known as ‘institutes’ or ‘rests’, they provided libraries, a place to send and pick up mail (hugely important in the days before telephone and internet), letter writing facilities, and alcohol-free games and entertainment as well as religious services.[8] The missions were open to sailors of all nationalities and faiths, the ‘men and boys landing in a city where they have no friends and no one seems to care for them’.[9]

Figure 3: Seafarers, c. 1910. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

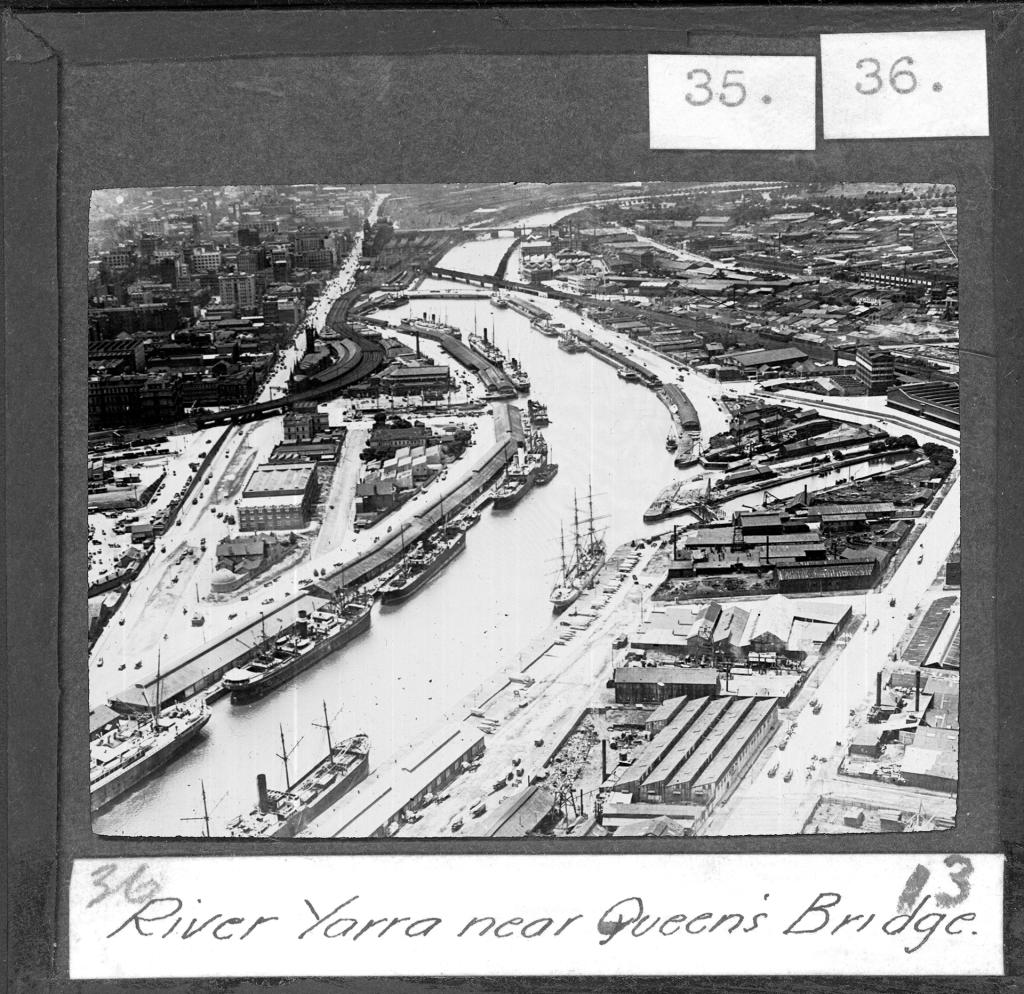

The pattern of missions was always to be as close as possible to where seafarers were. When late nineteenth-century water engineering works brought commercial shipping up the Yarra River right into Melbourne’s heart, there was a need for welfare services in the city docks. This is why the Melbourne mission was built in this location.[10]

Though Melbourne remains heavily reliant on commercial shipping, mechanisation and the advent of container ships means seafarers no longer come up the Yarra. Nowadays ships dock further to the city’s west. But the mission has kept operating from its CBD location. According to the volunteers who understand the history, 717 Flinders Street is globally unique. To date, they have not found any other mission that has kept performing its original function for such a long time in the same custom-built facility. ‘We think it’s the oldest one in the world’, Gordon Macmillan, then chair of the heritage committee, told me in 2019.[11]

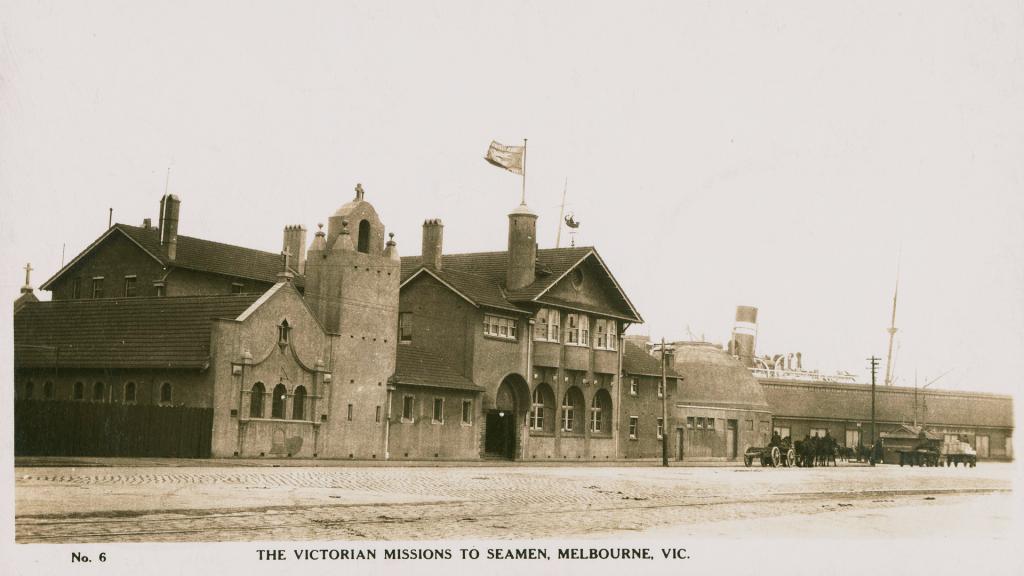

Figure 4: Melbourne Central Institute, c. 1920. PROV, VPRS 8357/P0001/63, Photograph [108], Postcard of the Victorian Missions to Seamen, Melbourne Victoria, undated.

A glimpse inside

Designed by Melbourne architect Walter Butler, the building is considered a significant exemplar of early twentieth-century Arts & Crafts and Spanish Mission style.[12] Passersby look curiously at the interesting façade, the unusual dome and the Art Nouveau lettering on the doorway arch. Signs say ‘open to the public’ but people rarely come inside. Those who do find a mosaic-decorated, maritime-themed foyer that opens on the left to a courtyard garden and cloister, at the end of which is a small, non-denominational chapel. Sometimes, if the chapel doors are open, you can go in. Stained-glass windows fill the space with a dreamy blue light; a wooden pulpit in the shape of a ship poop deck juts backwards towards the pews. Seafaring motifs are everywhere.

Turn right at the foyer and you enter a spacious room with a bar in a corner and a stage at the end (yes, the very stage beneath which the archives were discovered). This main club room, designed for a different era of large ships crews and many visiting sailors, can be busy, but often is sparsely filled with quiet groups of ship workers here to pay a visit to the city or talk to their families via video link. Occasionally they play snooker or other games. Sometimes someone will pick up a guitar by the stage and strum a song from their home country. Photos of nineteenth-century sailors adorn the walls.

Beyond the club room is a round room with a domed roof inspired by the dimensions of Rome’s Pantheon.[13] It was originally a gymnasium but is now used for functions and exhibitions.

Though over one hundred years old and showing wear and tear, the building has a surprising peacefulness to it. It is a comfortable space. Historian Chris McConville describes it as ‘a gem of a building’. ‘It’s hard to think of other buildings that were built for working class people’, he says, ‘designed with this sort of human scale and a sense of how people would use the building, and how they would feel comfortable in it.’[14]

Victorian State Architect Jill Garner agrees. To her, Walter Butler wound into the building’s narrative a unique offer to seafarers of ‘somewhere that’s spiritual, that gives them a place to remove themselves from the street outside’. It tries to ‘give them a home in a city that’s possibly not their home’.[15]

Ship workers might only be here for hours while the containers are unloaded and loaded, instead of weeks at a time as was once the case, but seafaring remains lonely and dangerous work and the respite offered by the mission can still mean a lot. Today, as they did one hundred years ago, seafarers struggle with exploitation, poor pay and bad health. A small core staff, a chaplain and a network of mission volunteers called ‘Flying Angels’ ensure that the mission is open every day, including weekends and public holidays. The Flying Angels drive community buses and collect seafarers from the vast docks of Melbourne’s west. Seafarers who visit the mission do so to get connected with medical services, to get access to fresh food shops or just to do some sightseeing. The Flying Angels and the mission’s resident chaplain also visit ships to provide outreach.

One day, while filming, we went up to the heights of the KPMG Tower that overlooks the mission. Seen from above, the community buses were in constant motion—little white rectangles weaving in and out of city traffic, bringing seafarers back and forth.

Figure 5: Aerial photograph of the Yarra River, c. 1920. The Mission to Seafarers is in the middle lower left of the image. PROV, VPRS 8360, Numbered Lantern Slides, 35 River Yarra Near Queens Bridge, Undated.

The archive

The dusty boxes stored under the stage contained well-preserved minute books, letters books, visitor logs, ship visit logs, scrapbooks of newspaper clippings, annual reports and newsletters of the organisation dating back to the 1850s. The archive is particularly rich in material and photographs from the early 1900s when the Melbourne mission building (or, more accurately, buildings) was built.

After 2007, once the archive was rediscovered, a dedicated community of staff and volunteers began sifting through the documents. A heritage significance assessment was commissioned that helped consolidate a planned program of discovery and publicity.[16] Working on site in a room that, as the mission’s then-curator and lead archivist Jay Miller told us in 2019, was too cold in winter and too hot in summer,[17] their task was to store the collection in a suitable setting, and then to sequentially work through the objects, cataloguing, labelling, digitising, undertaking additional research, and uploading images and object descriptions onto the public facing Victorian Collections online portal.[18]

The work hasn’t finished yet. Ten thousand items are a lot to get through. It is slow work, but also fascinating. Each document pored over unlocks deeper connections to the place. Every annual report or newsletter provides clues or clarification.

Manchester-based geographer Uma Kothari was a visiting professor at the University of Melbourne in 2017. She observed the diligence and excitement of the archive work at close hand. A spontaneous decision to see what went on inside the mission building led to her joining the activity, sitting alongside the volunteers working through the archives—an experience made more meaningful because it happened in situ surrounded by the ‘busy comings and goings of seafarers, staff and visitors’. She experienced a ‘profoundly personal entanglement with the place and its rich history’, and she could see others around her were similarly engrossed and rewarded.[19]

Like Kothari, we observed something special in the journey of the archival explorers as they worked in the setting of the living mission, unpacking the complicated history of the building and its people. Much of it was already known, but the archives helped fill in the details of sketchy timelines, or confirm events through the cross-checking of reports. And some of the story was a complete surprise. As Kothari found, it was tempting to jump in and join the research adventure.

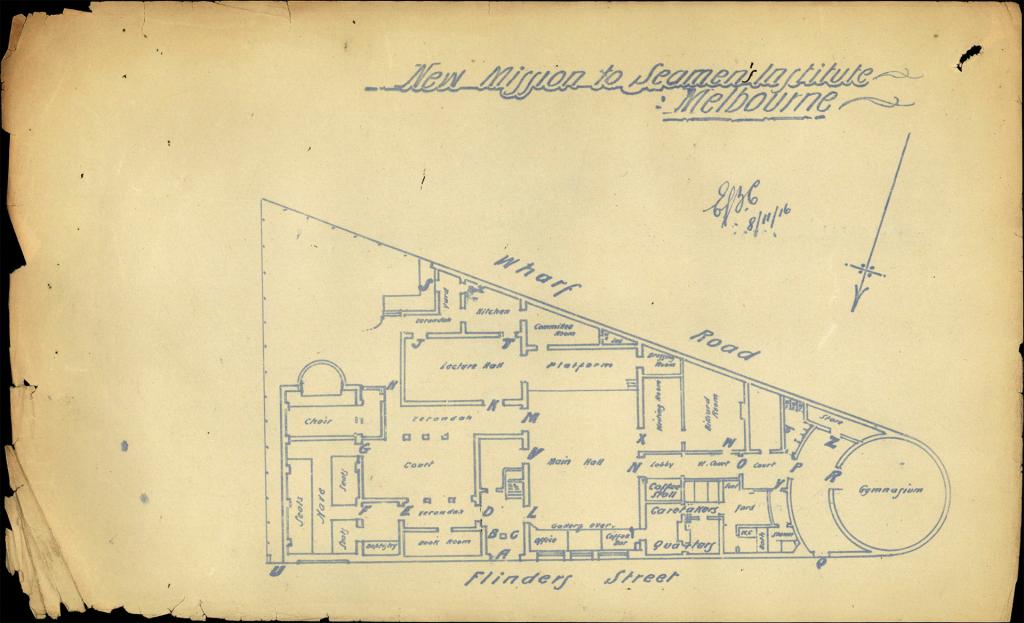

Figure 6: Plan of new buildings for the Mission to Seamen, 1916. PROV, VPRS 7882/P0001, 2071, Public Building Files, Seamen's Institute Australian Wharf Flinders Street Extension.

One mystery the archives helped to untangle was the confusing presence of apparently two mission buildings in the one place. The mission opened its first ‘Central Institute on Australian Wharf’ in 1906.[20] This building is today known as the Siddeley Street Mission, and, surprisingly, it was occupied only briefly. The annual reports in the archive help to explain why. The mission’s landlord, the Melbourne Harbour Trust, a powerful government organisation in charge of Melbourne’s ports, needed the site for future wharf extensions.[21] Forced to relocate, the mission built a replacement institute practically next door. This opened in 1917 and is the Flinders Street building in existence today.[22] Both buildings were designed by Walter Butler.[23] Butler proposed an ambitious Arts & Crafts and Spanish Mission–inspired complex, incorporating a domed gymnasium, recreation hall, chapel, garden and chaplain’s residence, for the second iteration.[24]

The two mission buildings and their construction dates provide a useful cross-reference for volunteer research teams in dating archival photographs, as images with the Siddeley Street façade or interior can only have been taken between 1906 and 1917. However, the fact that both buildings were designed by the same architect and called the ‘Central Institute on Australian Wharf’ makes for bewildering research. Understanding the Siddeley Street – Flinders Street chronology seems a kind of initiation for those learning to tackle the archives. One day, after inquiring about an image, I was told by a bemused volunteer researcher—‘oh, but that’s Siddeley Street!’, as if they were relieved that it all finally made sense.

Figure 7: Cricket match, c. 1910. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

Forgotten women

One of the archive’s particular strengths is a subcollection of photographs, letters, reports and minutes of a women’s auxiliary group called the Ladies Harbour Lights Guild (often referred to in the archive as the ‘Ladies’ or the ‘Guild’).

The LHLG was part of the fabric of Melbourne’s Mission to Seafarers up to the 1960s and a feature of other such missions in Australia and globally.[25] Women of the guild undertook volunteer domestic chores, put on teas, did fundraising, knitted beanies, held social events, wrote letters to sailors and partnered visiting seafarers at mission-run dances.

The mission recognised and appreciated the LHLG’s importance. A pair of large stained-glass windows in the chapel to a Miss Godfrey and a Miss Tracy honour them as guild founders. Miss Godfrey’s window depicts ‘Faith’, Miss Tracy’s ‘Hope’. The windows were erected in the 1930s after their deaths.[26] Yet, though the extended mission community remembers the last decades of the LHLG fondly and well, the foundational period of the guild and the contributions of misses Godfrey and Tracy stretched further back than oral histories could recall. Very little was known of them.

The archives, however, provide a detailed picture of the origins of the LHLG. From the early 1900s at least up to the 1930s,[27] quirky updates in the newsletter Jottings from Our Log, and chaplain’s reports and guild secretary updates in the annual reports, mention the guild constantly and effusively. Early twentieth-century photographs in the archive contain fascinating images of guild women in long white dresses and broad brimmed hats at outdoor events, playing cricket with seafarers, laughing at picnics: women who stare right at the camera and smile.

It turns out the women of the guild played a major role in the foundation of 717 Flinders Street. This realisation was a powerful surprise for the research staff and volunteers who cared deeply that the early work of the guild had been almost completely forgotten. The community made it a goal to tell their story.[28]

By the time we filmmakers came along, many identities had been sorted out and their personalities were very present. Miss Ethel Godfrey, the one in the chapel stained-glass window, was a well-connected Melbourne socialite who founded the LHLG and led it for 25 years as honorary secretary.[29] She was often pointed out to me and I was soon able to pick out her strong face in the photos. She was an object of fascination to many of us, not least because she was a mature, independent and obviously competant woman whose achievements had apparently been lost to time. The daughter of an elite squatter family, Miss Godfrey was a trained singer who mingled in Melbourne’s highest social circles. She also, surprisingly, became an articled law clerk in 1895, when she was 34 years old.[30] ‘So many strings to her bow’, sighed Jay with what sounded like admiration mixed with awe when we interviewed her for the film.[31]

Figure 8: Ladies Harbour Lights Guild, c. 1920. Miss Godfrey is fourth from right in the centre middle row with a child on her lap. Miss Tracy is on Miss Godfrey’s right on the middle row, third from the left. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

Miss Godfrey formed the LHLG in 1906, aged 45. This was at the beginning of the Siddeley Street era, after a newly arrived chaplain, Alfred Gurney-Goldsmith, had invited women to become more involved in the mission.[32] Miss Alice Sibthorpe Tracy, the woman in the other stained-glass window, joined shortly after and would serve for many years as honorary treasurer. ‘I love Miss Tracy’, a researcher told me: ‘She has such an interesting face!’

Miss Godfrey, Miss Tracy and the LHLG were formidable networkers and fundraisers who built up a system of regional and suburban branches of women subscribers. Jay Miller described the membership as a ‘who’s who of Melbourne’.[33] Guild patrons were the wives of governors-general, governors and mayors.[34] High society members paid a large subscription fee of a guinea and hosted seamen’s picnics and social fundraising events at their leafy mansions.[35] ‘Working’ or ‘half-crown’ members paid a more modest subscription and volunteered time at the mission.

Subscribers included Lady Fraser, after whose Toorak mansion ‘Norla’ the Mission’s gymnasium was named; philanthropist Helen Macpherson Smith; the Armytages of Como House Toorak; Lady Syme, wife of the owner of the Age; and the Forge sisters of the Forges department store family empire.

Although ‘guinea’ members may not have set foot in the mission, ‘working’ members certainly did. They joined subgroups such as the Flower Guild (for decorating), Dusters Guild (for cleaning) and Literature Department (cataloguing and parcelling literature). Volunteers cooked in the mission canteen, served at the Post Office, prepared events and performed music.

Figure 9: Seafarer holding a letter or flyer, c. 1910. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

Entertainment was a major responsibility of the LHLG, the managing of which was Miss Godfrey’s specialty.[36] Sailor entertainments took the form of wholesome pro-temperance ‘tea and rock-cakes’ socials at which visiting seamen would sing shanties or play drafts.[37] Other events included Sunday evening concerts and regular public holiday picnics and outings, as depicted in those evocative photographs. In 1910, the guild held 313 social events for 18,035 visiting seafarers to the Central Institute.[38]

Encouraged by marketing campaigns devised by Miss Tracy, donations flowed in.[39] These came in the form of gifts of furniture, books, musical instruments and multitudes of hand knitted ‘woollies’ for sailors, but there was also a lot of cash. ‘The Institute couldn’t have kept out of debt but for the “Ladies Harbor Lights’ Guild”’, Miss Godfrey stated with a smile in an article written in 1910.[40]

By 1911, the LHLG counted 300 honorary (‘guinea’) members and 577 working (‘half-crown’) members and had established 21 branches in Victoria, including in four regional towns.[41] Over the next decade this would grow to 51 branches and 10 school branches in Victoria.[42] The subscriber and branches model would be imitated across Australia and in missions around the world.[43]

For historian Kate Darian-Smith, one of the most interesting things about the LHLG’s activity is the people-to-people exchanges that took place between the middle-class Melbourne women of the guild and the seafaring men from different nations and different backgrounds to whom they offered hospitality. Although ‘this is not something that would be picked up in the minutes of the guild or in any of their archive’, Darian-Smith observed, the women of the guild ‘perhaps stepped outside of their own immediate experience to connect with a range of different cultures, different moments’.[44] ‘They wanted Melbourne to be a hospitable place for strangers’, she remarked, ‘and I think that is a really nice way to think about what was happening in the building.’

Figure 10: Stained-glass window to the honour of Miss Ethel Augusta Godfrey, 1935. Photograph by Justine Phillip 2013. Courtesy of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria.

Names in the chapel

When WWI broke out in 1914, the LHLG, like many other women’s charitable groups at the time,[45] sprang into patriotic work, making comfort packs for the Red Cross and sending Christmas billy cans to the Australians at Gallipoli.[46] At around this time, the second Central Institute needed to be built. The guild took on the responsibility to raise the money for the chapel. By 1916, they had raised a whopping £1,000, enough for the entire chapel’s build.[47]

In light of the horrific experiences of WWI, the mission decided to dedicate the chapel as a war memorial in honour of the mercantile marine. A call was sent out for donations for memorial items for the chapel, which today has a moving collection of memorial gifts and plaques donated by people directly impacted by the war. Architect Walter Butler lost his only son. A guild member known only as ‘Mrs R’ died working as a stewardess on a passenger boat sunk by a mine.[48] Dedications included stained-glass windows donated by the Forge sisters in memory of their dead brother, and a memorial font for two child apprentices who died with nine other crew when their ship was torpedoed by a U-boat.[49] The second Central Institute and its chapel was formally opened in September 1917, in an unusually quiet dockland precinct in the midst of a general waterfront workers strike.

Guild activity continued after the war, but, by the 1930s, with the deaths of Miss Godfrey and Miss Tracy, the heyday of its founding membership had passed. The guild would continue, evolving to different circumstances under new leadership, up to the 1960s.

Given the work the LHLG put into that dreamy blue chapel, the stained-glass window memorials to Miss Godfrey and Miss Tracy make complete sense. And, although it took some time to remember them, their deeds stowed away in those dusty boxes under the stage, the work of connecting and piecing together their stories was profoundly satisfying for the mission community.

In my encounter with the mission and its archive, I discovered that the ‘what comes next’ of exploring an archive of rare significance is anticlimactic. It involves hours of slow, diligent, unsung, mostly boring work. Yet, at the same time, the work is also absorbing and rewarding for those who undertake it. The previously obscure names of people from the past, the ones looking out at you in old photographs, the ones who appear on plaques on walls, become deeply significant. An archive is indeed an adventure that can lead to hidden treasure, unearthing long-forgotten stories of Melbourne’s rivers and ports, of hardworking, under-appreciated seafarers and of formidably competant women.

Archives are complicated. The Mission to Seafarers archive is enmeshed in the place it was found, the organisation it belongs to and the work of the people around it. The past is woven into the fabric of the present. Everything waves and shifts, alive to the changing headwinds of an evolving city. When it comes to unravelling the threads of stories here, it feels very much like we are still wound up in them.

Endnotes

[1] Thank you to the community of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria for their generosity and their help with this project. Particular and special thanks go to Jay Miller, Gordon Macmillan, Sue Dight, Geraldine Brault, Cinda Manins and Nigel Porteous. The writing of this article was supported by a Victorian Government Sustaining Creative Workers grant.

[2] Liz Hobday, ‘Treasure trove of seafaring history goes on display in Melbourne’, ABC News, 28 July 2016, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-07-28/treasure-trove-of-seafaring-history-goes-on-display-in-melbourne/7670724>.

[3] There are 230 mission sites around the world and four in Victoria (Melbourne, Portland, Geelong and Hastings).

[4] As far as I can ascertain, ‘Australian Wharf’ was the area of the Yarra River on the north-western bank approximately opposite where Polly Woodside is today. Flinders Street and Siddeley Street adjoin this area of the Yarra bank.

[5] The mission’s annual report for 1917 recorded 13,617 attendances to the Central Institute that year. This was fewer than usual because of the effects of the war. In comparison, 22,612 sailors had attended the institute in 1913. See Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1913, p. 8, and Annual Report, 1917, p. 7, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[6] The ‘Flying Angel’ Story: The History of the Mission to Seafarers, Mission to Seafarers, London, c. 2015.

[7] The ship was called The Emily.

[8] History sourced from WHC Darvall, Victorian Seamen’s Mission and Rest origin and epitomised history of matters of interest in connection herewith, c. 1906, and Victorian Missions to Seamen, Annual Reports 1910–1917, both from the Mission to Seafarers Heritage Collection. See also ‘Seamen’s floating church in Hobson’s Bay’, Argus, 2 July 1857, p. 5.

[9] RJ Alcock & WHC Darvall, ‘Victoria Missions to Seamen’, letters to the editor, Age, 1 June 1906, p. 8.

[10] An original 1897 petition by the captains of 21 ships to the Victorian Seamen’s Mission for a facility to be built nearer the Yarra River wharves is part of the Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[11] Gordon Macmillan, personal communication, 2019.

[12] Victorian Heritage Database, Missions to Seamen, Heritage Council of Victoria, available at <https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/756>, accessed 23 October 2022.

[13] ‘Gymnasium of novel design to be lighted from dome’, Herald, 23 October 1919, p. 13.

[14] Chris McConville, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks, Wind & Sky Productions, Melbourne, 10 June 2019.

[15] Jill Garner, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks, Wind & Sky Productions, Melbourne, 4 August 2019.

[16] Catherine McLay, ‘Supporting seafarers: Mission to Seafarers Victoria’, Signals, no. 110, March–May 2015, pp. 57–61.

[17] Since our visit in 2019, the Melbourne Mission to Seafarers has undergone a renovation and the archives room has subsequently been moved to a different location, though I understand the collection is still largely worked on on-site.

[18] Mission to Seafarers Victoria, available at <https://victoriancollections.net.au/organisations/mission-to-seafarers-victoria>, accessed 23 October 2022.

[19] Uma Kothari, ‘Seafarers, the mission and the archive: affective, embodied and sensory traces of sea-mobilities in Melbourne, Australia’, Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 72, 2021, p. 74.

[20] Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1907, p. 5, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[21] Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1911, p. 3, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[22] For reasons unknown, the Siddeley Street Institute building was not demolished. The building’s profile can be seen in photographs up to at least 1959.

[23] The 1906 (Siddeley Street) design by Walter Butler is held at the State Library of Victoria but the 1917 Flinders Street building design has not been preserved, although a floor plan is held at PROV (VPRS 7882/P0001, 2071).

[24] The gymnasium would have to wait until 1920 to be opened. See Victorian Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1918, p. 8, and Jottings from Our Log, no. 58, Easter, 1920, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[25] Some jurisdictions called them ‘Lightkeepers’. See AAW, ‘Miss Godfrey of Melbourne’, Church and the Sailor, July 1930, p. 85, Mission to Seafarers Heritage Collection.

[26] The text of Miss Tracy’s window dedication says it was erected in 1933 after her death in 1932. Miss Godfrey’s dedication states it was erected in the year of Miss Godfrey’s death. Miss Godfrey died in July 1935. See Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1935, p. 11, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[27] These years (1900s–1930s) were as far as our research frame extended.

[28] Jay Miller, personal correspondence, 2019.

[29] Geraldine Brault & Jay Miller, ‘The soprano and the seafarers: a woman with a mission 1906–1930’, Genealogist, vol. 17, no. 2, June 2020, pp. 19–21.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Jay Miller, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks, Wind & Sky Productions, Ballarat, 29 June 2019.

[32] AAW, ‘Miss Godfrey of Melbourne’.

[33] Jay Miller, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks.

[34] Information in these paragraphs is drawn from a sample of Annual Reports, 1906–1920, in the Mission to Seafarers Heritage Collection.

[35] Events reported in 1906–1920 include picnics for seafarers, fundraising fetes and drawing room meetings held at mansions in Toorak, St Kilda, Armadale, Brighton, Malvern, Hawthorn, East Melbourne, Kew and Canterbury, as well as zoo and river excursions.

[36] Miss Godfrey, who was the daughter of the prominent businessman and pastoralist FR Godfrey, studied singing in Europe in the 1870s and 1880s. She was more a society than a professional singer but sang at public events in various town halls and churches around Melbourne in the 1890s–1900s and is credited as the organiser of other entertainments. In 1896 composer Albert Mallinson wrote a song for her, and in 1903–1904 she performed a public concert series with the pianist Alice Spowers. See Brault & Miller, ‘The soprano and the seafarers’; ‘A grand concert’, Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 14 November 1903, p. 5; ‘Garden party at the zoo’, Punch (Melbourne), 31 October 1901, p. 21; ‘Chamber concerts’, Argus, 2 April 1904, p. 15; ‘Miss Ethel Godfrey’, Table Talk (Melbourne), 19 March 1903, p. 15.

[37] ‘Miss Godfrey—Harbour Lights Guild—Wayfaring Men’, Weekly Times, 3 September 1910, p. 10.

[38] Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1910, p. 7, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[39] Reports often mention Miss Tracy’s fundraising schemes. See, for example, the collecting card initiative in 1916, Jottings from Our Log, no. 44, Michealmas, 1916, Mission to Seafarers Heritage Collection.

[40] ‘Miss Godfrey—Harbour Lights Guild—Wayfaring Men’.

[41] Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1911, pp. 11–12, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[42] Victoria Missions to Seamen, Annual Report, 1924, p. 8, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[43] AAW, ‘Miss Godfrey of Melbourne’.

[44] Kate Darian-Smith, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks, Wind & Sky Productions, Melbourne, 10 June 2019.

[45] According to Kate Darian-Smith, women’s organised charities became extensive by 1915. This included such groups as the Red Cross and the Women’s Comfort Fund as well as local women’s fundraising groups. Kate Darian-Smith, interviewed by Lucinda Horrocks.

[46] Jottings from Our Log, no. 40, Michaelmas, 1915, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[47] Jottings from Our Log, no. 47, Midwinter, 1917, Mission to Seafarers Victoria Heritage Collection.

[48] Jay Miller, personal correspondence, 2019.

[49] Jottings from Our Log, no. 44.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples

![Melbourne Central Institute, c. 1920. PROV, VPRS 8357/P0001/63, Photograph [108], Postcard of the Victorian Missions to Seamen, Melbourne Victoria, undated. Melbourne Central Institute, c. 1920. PROV, VPRS 8357/P0001/63, Photograph [108], Postcard of the Victorian Missions to Seamen, Melbourne Victoria, undated.](/sites/default/files/files/PROVENANCE 2022/Banner Horrocks.jpg)