Last updated:

‘Affect and the archive’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 19, 2021, ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Amanda Lourie.

This article considers affect and the archive. It was inspired initially by the work of historian Emily Robinson and muses on affective engagement with the materiality of the archive, archival discovery and the content of the archive. The author reflects on her own archival experiences within and outside the collections of Public Record Office Victoria.

The dusty microfilm containers filled me with dread. I had been avoiding them for some time, hoping that Trove would miraculously digitise the earlier years of the Warrnambool Standard and, in doing so, prevent me having to scroll through frame after frame of these microfilm in search of relevant information.[1] The layer of dust accumulated on them in their open wire baskets suggested that I was not the only one who had avoided using these archival sources. Yet these dusty boxes eventually brought me great joy and insight: I found an article that transformed my research and led to me finding a petition in the archives at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), now the primary focus of my investigation. When I first approached these microfilm containers, I was filled with dread at the task I was about to undertake. When I think about them now, they happily remind me of that ‘discovery’—of the thrill of finding something in the archives. Indeed, a photograph I took of the dusty boxes, initially in bemusement, is now an image of joy for me, made more so because of the act of having to search through the archival source in such a cumbersome way.

Figure 1: Microfilm boxes. Deakin University Microfilm collection, Melbourne Campus, 20 October 2019. Author supplied photograph.

I am an historian who has been researching Indigenous–settler relations for the last five or so years. It is impossible for me to think about my research without bringing emotions and affect into it. In part, this is because, even though there are pages of archives written about Aboriginal people, they can often be impersonal, official documents—measurements for clothing requests, lists of names of those living at a reserve, and the acreage harvested or length of fencing completed: in other words, surveillance records. Frustration, sadness and horror can abound in looking through these documents.

Searching through other archives such as letters, petitions and diaries can reveal the agency of Aboriginal people and their complicated relationships with settlers. Sometimes it takes what historian Inga Clendinnen calls ‘deliberate double vision’ to move oneself beyond the author’s own reactions and observations, but those moments are important to my research and the discovery is incredibly satisfying.[2] Those moments also render an importance to the archival source and I often find myself pondering over them—taking in and tracing over the writing, turning the pages in my hand, breathing in the old paper smell (or listening to the rewinding of the microfilm roll).

In writing this I cannot move forward without acknowledging that, as a non-Indigenous historian, my engagement with the archives differs from others. Work by Indigenous scholars, such as Gimuy Walubara Traditional Owner Professor Henrietta Marrie, Darumbal and South Sea Islander journalist Amy McQuire, Narungga woman and activist-poet Dr Natalie Harkin, Wiradjuri man and Australian Museum project officer Nathan Sentence, and Worimi professional archivist Kirsten Thorpe, discusses archives as sites of colonial power, violence, state mediation of Indigenous voices and representations, and silences.[3] When I enter an archival space or look at an archival record, I try to remember that archives are ‘unreliable witnesses’.[4] My work in them can reveal and challenge some of these representations, but I must be vigilant in this work and it is best done with community. What follows are my musings on affect and the archive.

Historian Emily Robinson wrote of the affective experience of history some years ago now. She described this as a part of history little written about, but something that enabled history as a profession, practice and academic discipline to ‘withstand the challenges of post-structuralism and postmodernism’.[5] Robinson described engaging with archival documents as a ‘powerful’ affective experience, one that encompassed sight, smell and touch. She argued that historians appeared to downplay or ignore writing about their ‘excitement’ about the past to avoid claims of ‘sentimentalism’.[6] Yet it was this ‘appeal’, the ‘pleasures’ of historical work through this ‘affective dimension’, that had enabled history to ‘persist’, to continue as important and relevant beyond the academic challenges of post-structuralism and postmodernism to the present. For Robinson, the ‘affective character’ of history was, in part, a response to the paradox that she saw between the ‘irresolvable tension’ of being able to physically, literally touch the past in the form of archival sources, while also knowing that those archives simultaneously embody an otherness that is unknowable in its entirety.[7]

I am not sure that the excitement I experienced at my discovery will make it into any academic writing I do. Yet, when I first read Robinson’s article, I immediately responded to her notion of archival documents having a powerful affective response. And not just in regard to my microfilm find. For example, I can remember standing in the reading room at PROV looking through some archival sources. I had to stand, as it was the best way to be able to read the large rate books I had ordered. I had a trolley next to me piled high with multiple rate books from the late 1800s. They were handwritten, bound in leather and covered residences in the streets of Collingwood.[8] I pored over the archival resources, bent at the waist as I leaned forward to read the entries. The size and number of the rate books drew over another reading room visitor to ask about them. The search for pertinent information was fruitless. Unable to find evidence of the family I was researching, my only finding on this occasion was a record of absence within the archive. However, upon placing the last rate book back on the pile and looking at my blackened hands, I remember feeling a sense of delight at the physical reminder of the accumulation of dust over the years on these rate books. Thus, while my search had revealed little of what I had hoped, an experience quite familiar to historians undertaking research, I had nevertheless engaged with Robinson’s ‘powerful’ affective experience of the archives during my investigation. I had experienced delight at the neat nineteenth-century penmanship, the smell of the paper and leather and the grime that transferred from the rate books to my hands.

I am always happiest at PROV when I get access to original documents instead of heading down the back to the microfilm machines. I appreciate that technology ensures access to researchers while protecting fragile, important documents, such as reports and letters from the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, but they lose something in that flat, black and white reproduction on microfilm.[9] I am aware that PROV is digitising more of its records as I write. Sitting at home during various lockdowns, this makes me feel relieved about being able to continue my research. It also offers the capacity to search and view documents in other ways, including zooming in on difficult to read writing in an effort at interpretation. Historian Tiffany Shellam has written of zooming in on a digitised image that revealed something she had not been able to see in the original archive—the ‘faintly pencilled profile’ of a figure, Kuringgai man Boongaree, a person central to her research.[10]

Digitisation can facilitate access to records previously off limits for a variety of reasons, such as distance, cost, physical limitations and so on. However, as historian Lynette Russell has written, all archival records, whether viewed in their original form or not, can produce trauma.[11] Harkin, Thorpe and Cassandra Willis have articulated the trauma that the content of archives caused for them, their families and communities, beyond engagement with the written material.[12] For participants in the Koorie Archiving: Trust and Technology project, instigated by Gunditjmara man Jim Berg, archives can be ‘pretty heart wrenching’, representing only snippets of a person’s life, written from the perspective of officialdom.[13] As Thorpe argued, providing digitised records without ‘community engagement and participation in understanding the context of these collections to determine their future use and transmission’ is problematic. Indeed, many of the participants in the Koorie Archiving project identified being able to ‘talk back’ to the archive as important. This was a way to challenge the records, provide another perspective and, as Thorpe noted, ‘give voice to Aboriginal worldviews and perspectives’.[14] While digitisation provides researchers such as myself with the promise of greater access, this process is not so simple for others. As noted, for many Aboriginal people, archival records can be traumatic. Providing some context around the documents may be of benefit in the digitisation process: for example, explaining how and why the records were collected and the language used. Ensuring a process of permissions and the capacity to make information private is good practice. While my thinking on this has been informed by Indigenous scholars and communities, there would be many others who would benefit from similar consideration. Work by organisations and institutions such as Find and Connect and PROV, who were involved in the Koorie Archiving project, show that such considerations are starting to be made.

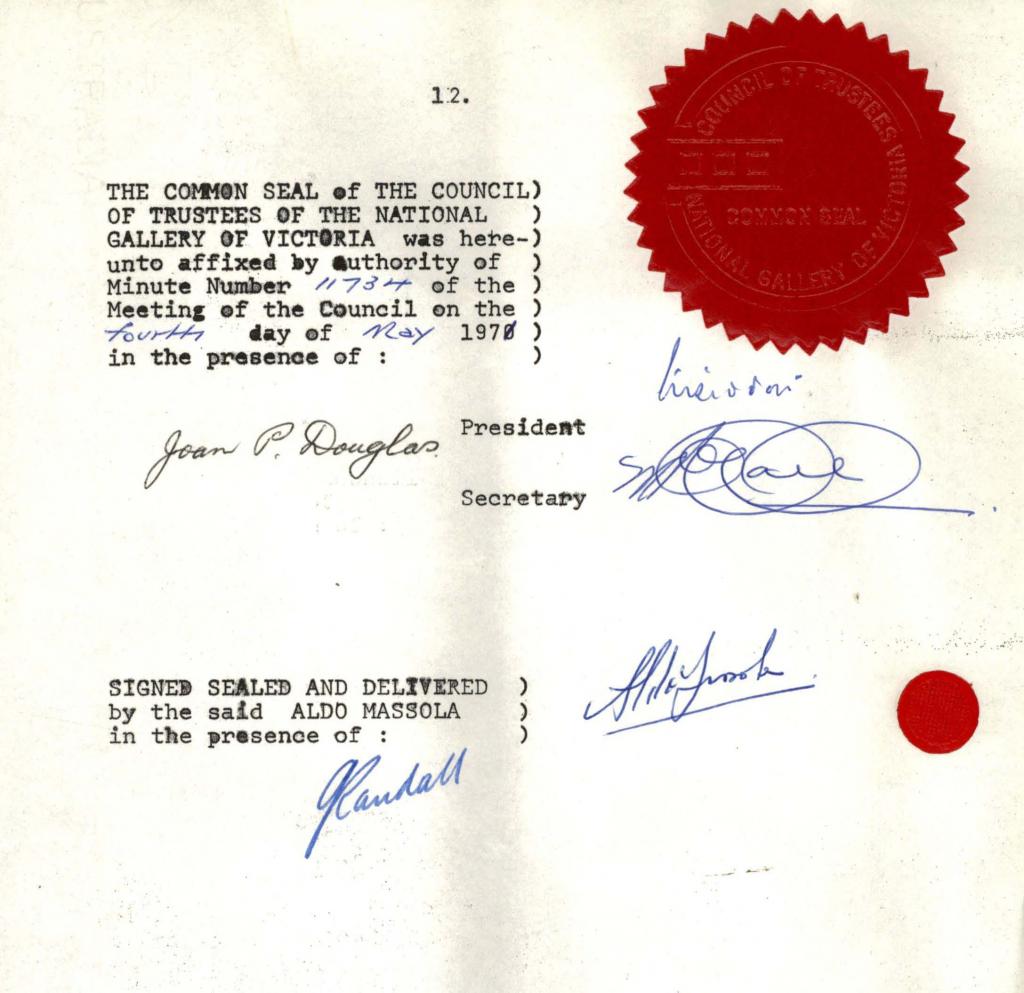

For me, seeing documents, being able to hold them and turn them over allows for a focus not just on their content but also their construction. To see possible hesitation marks made by a pen, to read the word under a line crossing it out, to identify how many different ways a page has been folded—these activities add to the information about a document. Equally, being able to hold a document in one’s own hands when a discovery is made adds to the unearthing. I know being able to gently rub my hand over the National Gallery of Victoria’s seal on court documents related to former curator Aldo Massola’s trial for stealing coins from the Museum of Victoria during the late 1960s and early 1970s added a tactile element to my engagement with these pages, as well as a sense of gravity with the seal’s embossed profile indicating officialdom.[15] Seeing the rips and crinkles on a letter written by Gunditjmara parents asking for a railway pass to visit their son before he travelled overseas to fight in World War I amid a collection of carefully folded letters from reserve managers and Board for the Protection of Aborigines (BPA) authorities leads one to wonder about how these different letters were valued and stored before making their way to PROV.[16] Seeing and feeling the fragility of the paper from over a century ago reinforces the preciousness and value of being able to read these documents in their original form.

Figure 2: Common Seal of the Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 1971, PROV, VA 930 National Gallery of Victoria, VPRS 13116/P1 Administration Files, Unit 16 A, Massola – [Theft of Coins], 12 January 2019. Author supplied photograph.

Robinson’s consideration of the allure of archives was in relation to original archival documents. She noted that, while digitisation provides access to documents that might otherwise be out of reach, digital archives cannot generate the same affective response an historian gets when seeing, touching, feeling and smelling original archival documents.[17] But can this affective response only be achieved in relation to original documents?

In my case, I am not sure that finding the article that brought me so much joy in an actual, physical newspaper would have increased my happiness. While the article itself was illuminating and unexpected, it was the information, the content of the article, rather than the form of the archive, that I responded to. The newspaper was from 1889. Given the fragility of paper and capacity for ink to fade, having some form of digitised (or microfilmed) version is essential to ensure that we have continued access to the record. The fact that the original archival newspaper was removed from direct human production, itself produced via printing machines after the text had been set by human hand, may have tempered my affect at the original archival source. It may also be that, while Robinson focused on the material archive, my microfilm moment was more around the effect of the content of the archive.

Historian Katie Barclay has written of both crying and laughing in an archive. She described the horror and distress she felt in ‘empathetic engagements’ with her subjects.[18] Barclay has been guided, or possibly compelled, by this emotional response to research and write about her historical subjects. She was interested in how historians’ ‘love of the dead becomes implicated’ in their work and posited that among the ethical obligations of historians as ‘witnesses and storytellers’ was giving voice to others. This demanded empathy and emotions and led to complex and multilayered histories.[19] Russell, in an engaging personal reflection on working in archives, admitted to having fallen ‘a little bit in love’ with sealer and whaler Tommy Chaseland.[20] Although important in her research, he was not a central figure, but a fondly considered one. As with Barclay and Russell, I have also been drawn to historical actors I have researched, especially William Blandowski and Charles Strutt. These men were not necessarily important within colonial society, although Blandowski has been central to my own research on occasion. They did hold government office, meaning there is some archival record of them. William Blandowski was employed as a government zoologist in 1850s colonial Victoria. He led a few expeditions across the colony and oversaw the start of what is now Museums Victoria. Charles Strutt was a medical doctor who travelled as a medical supervisor on ships carrying young orphaned Irish women to the Australian colonies in the 1840s. In 1858 he was appointed as a police magistrate on Yorta Yorta Country in Echuca. Seeing Strutt’s name on coronial inquests that centred Aboriginal people’s experiences and voices was poignant: it reinforced my sense of his attempts to engage with local Yorta Yorta people and, being written in his own hand, was exciting for me to see.[21]

Barclay examined the content of the archives—that is, the subjects contained within them. There is an affiliation between the affective response elicited by archival documents that Robinson described and the emotional responses to what is contained within those archival documents that Barclay considered. Both the documents and the content of the archives can elicit emotions within the historian. I have loved the dusty, grimy result of trawling through boxes of correspondence from the Chief Secretary’s Office—letters crammed into boxes and needing careful extraction. And, simultaneously, I have felt exasperated at the silences—at documents recorded as being received by the chief secretary during the 1880s and 1890s but not present within the box.[22] Experiencing such frustration no doubt heightened my joy at finally finding a sought-after letter.[23]

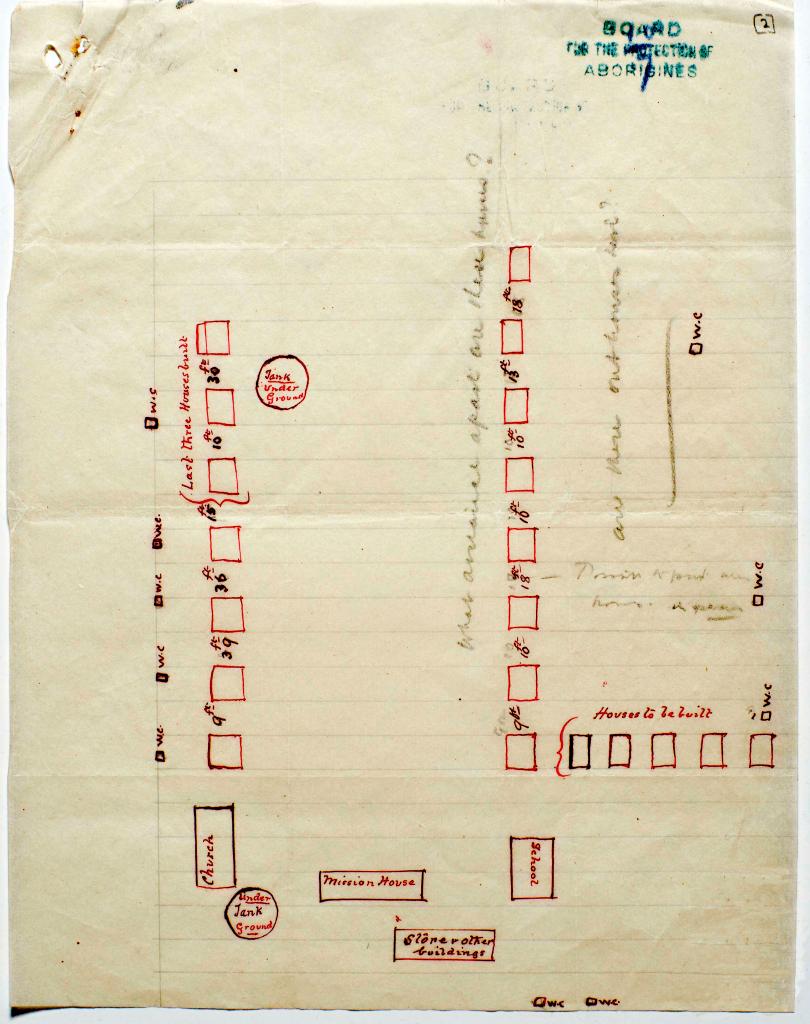

Having spent time reading about and researching Lake Tyers Aboriginal Mission manager John Bulmer, I was aware of the scrawl of his handwriting. Lake Tyers, or Bung Yarnda, was set up in the 1860s in Gippsland on Gunaikurnai Country, overseen by both the Church of England and the BPA. Many Gunaikurnai people moved there, and Bidawal, Yuin, Yaithmathang, Dhudhuroa and Ngarigo peoples visited on occasion. Bulmer was the manager from the mission’s inception in the early 1860s until the early 1900s. Seeing the care he took to draw a sketch of Lake Tyers, laying out the houses, church, school and store was touching.[24] Bulmer is an historical subject I have been drawn to as I have tried to understand both his advocacy for the Aboriginal people who lived at Lake Tyers and his role in the colonial project that simultaneously disrupted and devastated the lives of Aboriginal people in Victoria. I think this is why the hand-drawn map was so affecting. Bulmer had lived at that site for decades. Alongside Gunaikurnai men, he had constructed the buildings that he carefully rendered on the page. After Bulmer died in 1913, his wife, Caroline Bulmer, and daughter, Ethel, along with residents at Lake Tyers, fought unsuccessfully to have the buildings remain at Lake Tyers.[25] Historian Victoria Haskins has written about this campaign in an earlier edition of Provenance.[26] Bulmer’s sketch of the buildings of Lake Tyers caused an affective response in me, both in terms of its physical presence in the archive and its illumination of another aspect of Bulmer’s story—the regard and care he felt for Lake Tyers after years of advocacy as represented in his careful rendering on the page.

Figure 3: Sketch by John Bulmer of Lake Tyers buildings – 8/7/1907, amended 15/7/1907, PROV, VA 515 Board for the Protection of Aborigines, VPRS 1694/P0 Correspondence Files, Unit 2, 1907, Correspondence – Housing Lake Tyers and Coranderrk, 10 February 2017. Author supplied photograph.

In her Quarterly Essay, ‘The history question: who owns the past?’, Clendinnen noted the need for historians to keep their ‘emotions bridled by intellect’. Doing so resulted in histories that were better able to represent the lives, actions and cultures of past actors, to ‘penetrat[e] sensibilities other than their own’. Clendinnen reflected that this was not an easy task. While reading through archives that contained detailed descriptions of torture, Clendinnen had ‘brandy-and-water at [her] elbow’ to help her cope.[27] I have at times wished for my own version of brandy and water reading through reports of the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate and BPA meeting minutes.[28] These two agencies provided the surveillance of Aboriginal people for the British Colonial Office and the colonial and state governments. The recent digitisation of these documents has certainly been welcome, but they are not an easy read and I know they are hurtful for some community members. There is brutal language and descriptions in these archives, and there is horror in the banality of the bureaucratic language that blithely refused railway passes, separated families and ignored Aboriginal people across the colony and state who were advocating for themselves and others in their communities. Sadly, the banning of liquids in the PROV Reading Room prevents Clendinnen’s practice of brandy and water.

Clendinnen was instructing us how to research as historians. I think this bridling of emotions is important as it helps us to avoid the sentimentality of which Robinson warned. Yet, I say this from my privileged position of not having my ancestors written about in the context of colonisation. I am a benefactor of this process. Clendinnen may not have agreed with Barclay’s thesis of using emotions and emotional responses to guide one’s research, but both historians acknowledged the emotional power of the archive, especially in relation to its contents. When her intellect could no longer prevail over emotion, Clendinnen would stop her work for the day. Discussions around vicarious trauma have entered archival spaces, and are important in considering the affective power and trauma contained within some archives. The Australian Society of Archivists recently developed an online course: ‘A trauma-informed approach to managing archives’.[29] This recognises the trauma within certain archives and the effect—the vicarious trauma—this can have on those who engage with, and oversee, the archives. It is something that, having worked in mental health, I appreciate being considered.

Clendinnen observed the slow, challenging work of history. The memory of those dusty microfilm boxes still evokes excitement within me. I had been researching for months and finding the article revealed a relationship between settlers and Aboriginal people not previously written about that opened up further avenues for research. It simultaneously consolidated all the hard work previously undertaken and changed its focus. That archive became important to me in a way that I had not expected. I had had little affectionate feeling towards it as I began researching. Now, my retelling of both the act of discovery and the content of my find is filled with emotion. I am happy to say that those small boxes, covered in dust and containing scanned newspaper pages, provided a powerful affective experience.

Author’s note: I would like to thank colleague Jason Gibson for introducing me to Emily Robinson’s work and to the PROV editorial board for their assistance, especially Tsari Anderson and Sebastian Gurciullo.

Endnotes

[1] The Warrnambool Standard, 1879–1900, Newspaper collection, Microfilm, Deakin University, 1872–1949.

[2] I Clendinnen, Dancing with strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, p. 119.

[3] H Fourmile, ‘Who owns the past? Aborigines as captives of the archives’, in V Chapman and P Read, Terrible hard biscuits: a reader in Aboriginal history, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1996; A McQuire, ‘Black and white witness’, Meanjin, Winter edition, 2019; N Harkin, ‘Whitewash-brainwash: an archival-poetic labour story’, Australian Feminist Law Journal, vol. 45, no. 2, 2020, pp. 267–281; N Sentance, ‘Disrupting the colonial archive’, Sydney Review of Books, 18 September 2019; K Thorpe, ‘Ethics, Indigenous cultural safety and the archives’, Archifacts, no. 2, 2018, pp. 33–47; K Thorpe, ‘Speaking back to colonial collections: building living Aboriginal archives’, Artlink, vol. 39, no. 2, 2019, pp. 42–49.

[4] Sentance, ‘Disrupting’.

[5] E Robinson, ‘Touching the void: affective history and the impossible’, Rethinking History, vol. 14, no. 4, 2010, pp. 503–520, 504.

[6] Ibid., pp. 504, 505.

[7] Ibid., pp. 504, 517–518.

[8] PROV, VA 439 Collingwood (Town 1873–1876; City 1876–1994) Previously Known as East Collingwood (Municipal District 1855–1863; Borough 1863–1873; Town 1873), VPRS 377/P0, Rate Books, Unit 40, 1892–1893; Unit 41, 1893–1894; Unit 42, 1893–1894; Unit 43, 1894–1895; Unit 44, 1894–1895.

[9] PROV, VA 473 Superintendent, Port Phillip District, VPRS 4467 Aboriginal Affairs Records (Microfilm Copy of VPRS 4409, 120, 11, 4410, 12, 2895, 4399, 4397, 4398, 4466, 4412, 4414, 4465, 2897, 2893, 2894, 2896, 4411, 4415, 6760).

[10] T Shellam, Meeting the Waylo: Aboriginal encounters in the archipelago, UWA Publishing, Crawley, 2019, pp. 109–111.

[11] L Russell, ‘Indigenous knowledge and archives: accessing hidden history and understandings’, Australian Academic & Research Libraries, vol. 36, no. 2, 2005, pp. 161–171, 164.

[12] Harkin, ‘Whitewash-brainwash’; K Thorpe and C Willis, ‘Aboriginal histories in Australian government archives’, Los Angeles Archivists Collective, vol. 10, 2021.

[13] Koorie archiving: trust and technology – final report, 2008, Monash University, pp. 36–38, available at <https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/2373848/Koorie-Archiving-Trust-and-Technology-Final-report.pdf>, accessed 17 August 2021.

[14] Koorie archiving, pp. 36–42; Thorpe, ‘Speaking back’, pp. 45, 46.

[15] PROV, VA 930 National Gallery of Victoria, VPRS 13116/P1 Administration Files, Unit 16 A. Massola – [Theft of Coins].

[16] PROV, VA 515 Board for the Protection of Aborigines, VPRS 1694/P0 Correspondence Files, Unit 3, 1917 Warrnambool and Coranderrk.

[17] Robinson, ‘Touching the void’, pp. 509, 510.

[18] K Barclay, ‘Falling in love with the dead’, Rethinking History, vol. 22, no. 4, 2018, pp. 459–473, 460.

[19] Ibid., pp. 461, 464–465, 468–469.

[20] L Russell, ‘Affect in the archive: trauma, grief, delight and texts. Some personal reflections’, Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 46, no. 2, 2018, pp. 200–207, 202

[21] PROV, VA 2889 Registrar–General’s Department, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 171, 1866/221 Male (digitised copy, viewed online 24 May 2021); Unit 71,1859/874 Male (digitised copy, viewed online 5 July 2018); Unit 58, 1858/943 Male (digitised copy, viewed online 24 May 2021); Unit 120, 1862/133 Female (digitised copy, viewed online 24 May 2021); Unit 81, 1860/451 Male (digitised copy, viewed online 5 July 2018).

[22] PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 3994/P0 Register of Inward Correspondence III, Unit 15 O 1889; Unit 17, Q1890; Unit 40 P1902; Unit 14 N1889; Unit 41 Q1902; Unit 16 P1890.

[23] PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 3992 P/0 Inward Registered Correspondence III, Unit 310 89/10481; Unit 312 89/10803; Unit 331 90/689; Unit 315 89/11622; Unit 330 90/208; Unit 318 89/12225; Unit 322 89/13182; Unit 870 02/422.

[24] PROV, VA 515 Board for the Protection of Aborigines, VPRS 1694/P0 Correspondence Files, Unit 2 1907 Correspondence – Housing Lake Tyers and Coranderrk.

[25] PROV, VA 515 Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, VPRS 1694/P0 Correspondence Files, Unit 6 Bundle 2, General Correspondence.

[26] V Haskins, ‘Give to us the people we would love to be amongst us’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 7, 2008, pp. 1–11.

[27] I Clendinnen, ‘The history question: who owns the past?’, Quarterly Essay, vol. 23, 2006, pp. 1–72, 36.

[28] PROV, VA 473 Superintendent, Port Phillip District, VPRS 10 Inward Registered Correspondence to the Superintendent of Port Phillip District, relating to Aboriginal Affairs (digitised copy); PROV, VA 512 Chief Protector of Aborigines, VPRS 11 Unregistered Inward Correspondence to the Chief Protector of Aborigines – Reports and Returns (digitised copy); PROV, VA 473 Superintendent, Port Phillip District, VPRS 4467 Aboriginal Affairs Records (Microfilm Copy of VPRS 4409, 120, 11, 4410, 12, 2895, 4399, 4397, 4398, 4466, 4412, 4414, 4465, 2897, 2893, 2894, 2896, 4411, 4415, 6760); NAA: Central Board Appointed to Watch Over the Interests of the Aborigines, B314 Minutes of meetings, single number series, 1860–1885, ROLL 1; NAA: Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, B314 Minutes of meetings, single number series, 1885–1921, ROLL 2; NAA: Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, B314 Minutes of Meetings of the Board, 1921–1946, ROLL 7.

[29] N Laurent and K Wright, ‘A trauma-informed approach to managing archives: a new online course’, Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 48, no. 1, 2020, pp. 80–87.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples

![Figure 2: Common Seal of the Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 1971, PROV, VA 930 National Gallery of Victoria, VPRS 13116/P1 Administration Files, Unit 16 A, Massola – [Theft of Coins], 12 January 2019. Author supplied photograph. Colour image of common seal document](/sites/default/files/files/provenance 2021 images/banner LourieA-F02.jpg)