Last updated:

‘World War I on the Home Front: the City of Melbourne 1914–1918’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 15, 2016–2017. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Nicole Davis, Nicholas Coyne and Andrew J May.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article utilises Melbourne City Council’s Town Clerk’s Correspondence as a critical resource through which to examine the experience of World War I on the home front in an Australian city. It argues that an examination of such records shifts the balance of historiographical attention from the global to the local in critical ways, and, in so doing, demonstrates the ways in which the war permeated every facet of life within the municipality; from the day-to-day running of the city, its economy, public spaces, and social relationships, as well as broader understandings of loyalty, patriotism and citizenship. The article further argues the profound importance of this collection and the ways in which it can be used to tell the big and small stories of war in the city.

In the days prior to the outbreak of World War I, the clerks in the Melbourne City Council’s (MCC) Town Clerk’s office stamped and filed inward correspondence relating to council matters, as they and their predecessors had done since 1842. With no hint of what was to come revealed within the bureaucratic paperwork of the municipality, the same sorts of letters that had passed through the department since the beginning of colonial Melbourne were received and filed as usual during these days. Complaints about nuisances, applications for permissions for bands to march, an invitation to council members to visit the Working Men’s College, requests from the Electric Supply Committee to order incandescent globes from Europe, permit applications from local cricket clubs—all formed the minutiae of civic communications.

When the first letter was stamped on the morning of 28 July 1914,[1] the war would not be declared in Europe for another few hours, but the likelihood of conflict must surely have been on the minds of these men, their employers, the writers of the letters and the city. Some of these men or their friends in municipal employment would themselves go to war, and some would not return. These particular official documents, written by a diversity of individuals, gave no indication of the threat of conflict. No extant letter announces its beginning in these files, and the first indication that a war had erupted came eleven days later on 7 August—three days after Britain and, by extension, Australia had declared war on Germany—when the City Electrical Engineer wrote to the Chairman of the Electric Supply Committee: 'Sir, I have the honor to report that in view of the European War I have taken stock of several of our important materials which are imported from time to time from Europe [and included] CARBONS ... FILAMENT LAMPS ... [and] METERS'.[2] This war, to which Australia had now committed itself, was here represented purely as a potential disruption to the smooth running of civic business.

Over five years later, when what was now known as the Great War had ended, its impact still reverberated in the council’s records, the life of its employees and, by implication, the entire city and its citizens. On 16 January 1919, two months after the war’s end, letters were exchanged regarding the repeated absences of council employee Archibald Wardrop due, in the words of his doctor, to asthenia or a nervous debility. The junior draughtsman had enlisted in July 1915 and remained on active service in Europe for two years and seven months, serving at Gallipoli and in France. Returning to Australia in early 1918 after his service was terminated by the AIF due to unfitness for duty, he quickly returned on 1 July to his role in the City Engineer’s Office, which had been held for him during his service. Although the letters in this file do not explicitly state it, these numerous absences from his role were likely due to the effects of the war.[3] The letters show that the conflict affected not only the running of the council, through its impact on Wardrop’s health, but also had longstanding personal implications for the returned soldier until his death in 1961.[4]

This article introduces the series in which these two letters and thousands of others are preserved—the MCC’s Town Clerk’s Correspondence—and assesses its value as a lens through which to examine the experience of World War I on the home front in one Australian city. While these files have long been recognised and used by scholars to tell a diversity of tales about the city and its people, a small project begun in October 2014, with the 100th anniversary in full swing, to examine them in detail and investigate what effects the Great War had on the city and its people.[5] The project also aimed to digitise any documents relating to, or mentioning, the war within this large collection.[6] They would then be displayed on the long-running eMelbourne website[7] in order to bring the collection and its contents to a wider audience, facilitating access for students, scholars and the general public, and increasing its usability for those interested in the history of the city of Melbourne, including the experience of the war within it.[8] What the trajectory of the project unexpectedly revealed was that this was an even richer treasure trove of information than could have been imagined. The examination of the records demonstrated how the war permeated every facet of life within the municipality, from the day-to-day running of the city to the lives of its inhabitants and to occurrences that resonated on a worldwide scale for many years to come.

While it was expected that there would be significant mentions of the war within the municipal records, what the research revealed was that the impact of this period of conflict permeated the metropolis on multiple levels—from the everyday running of the council to the physical use and experience of the urban environment. The concerns of the war reflected in these letters display not simply the daily workings of the council, although this was the initial purpose of their collection, but reveal the deeper experience of the city: of individual lives, public spaces, trade, transport, concepts of patriotism, nationalism and citizenship, infrastructure, changing gender roles, international relations, the presence of the military, and interrelationships between municipal bodies and federal authorities. City life in wartime, as Jay Winter notes, is 'an overwhelmingly complex story'.[9] The research reinforced what a profoundly important collection this is and how it can be used to tell the big and small stories of war in the city. It also highlights the value of bringing a collection such as this to public attention, to make it more accessible to those for whom the archives are not within physical or conceptual reach.

The collection

The City of Melbourne Town Clerk’s correspondence files (VPRS 3181 and VPRS 3183) are a diverse collection of documents that record some of the minutiae of the daily life of the city and its operation. Disgruntled ratepayers, prosecutions for breaking by-laws, health reports on milk supplies, applications for council jobs, permission to march through the city, applications for factory licenses and myriad other topics are covered in these letters. Letters were also regularly exchanged between councils throughout Australia and overseas, often requesting information regarding the administration of the city, including during World War I. For many years the Town Clerk’s Correspondence has provided a wealth of information to scholars interested in the city of Melbourne. Andrew May’s work, for example, has drawn heavily on this collection in order to draw a vivid picture of the experience of the city of Melbourne and its inhabitants during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[10] Simon Purtell wrote about the great Nellie Melba’s visit to the city and her performance in the Melbourne Town Hall using material drawn from these boxes.[11] They have been used in reports prepared for the City of Melbourne on the cultural and historic significance of Royal Park, in online projects,[12] and for exhibitions.[13] Honours and doctoral students of urban history have delved into them to reveal aspects of the city’s urban history that might not be revealed through other primary sources.

With the letters all filed together largely in date order, those from 1914 to early 1919 form an assemblage through which the workings of the council and the life of the city itself during this period can be traced chronologically to assess changes and the effect of the war, as well as thematic threads that run through the correspondence and might be compared to the experience of this period in other cities in Australia and the world. The first consignment (P0) of VPRS 3183 includes a relatively small collection of miscellaneous documents, visual material and propaganda matter from Australia, France, America and England, all connected to the conflict: periodicals such as Life and Steads that contained articles about the war and advertising for war bonds; cartoon books like International cartoons of the war and Raemaekers cartoons; pamphlets, for example, Ambrose Pratt’s 'Why should we fight for England?'; letters, including from the Defence Department based in Melbourne, as well as representatives of the forces overseas; and the recruiting posters, with illustrations by Norman Lindsay, produced just before the end of the war.[14]

The second consignment (P1) of VPRS 3183 contains the boxes that comprise the main sequence of the Town Clerk’s Correspondence files for the period 1910–1919. Altogether there are 111 boxes that cover the period from the early days of conflict in late July 1914 until 18 January 1919, two months after its end. The Town Clerk’s Department filed around 7,000 to 8,000 such files every year and, for the purposes of this project, each was examined for any mentions of the war. Overall there were over 660 individual files (containing from two to hundreds of pages) in these boxes that were identified, and almost 5,500 individual pages digitised from them. These references to the conflict were not evenly distributed, with some boxes having no relevant material, while others contained a dozen or more. Many of the files were copied in full, although in a number of cases, not all of the pages were digitised due to the sheer number of the pages contained within, where at times only a handful might mention the war. Those where the conflict was only mentioned in consequence of a greater concern within the file, such as the Town Planning Conferences of 1917 and 1918, were still digitised as they demonstrated the effect of the war on everyday life.[15]

The home front

Among the immense body of Australian war historical scholarship, World War I has been looked at predominantly as a national experience. For the majority of the population, however, the experiences and much of their participation in the war occurred in the cities on the home front. Adopting a more local approach is important, therefore, in recalibrating national and local narratives and experiences.

WK Hancock’s Australia (1930) confined the impact of the war to a chapter about ‘foreign policy’,[16] while Ernest Scott’s Australia during the war (1936) saw Australia as a harmonious society that was strengthened by the experience of war.[17] His work detailed many of the political, economic and material conditions of the time, and his historic assessment of conditions on the home front stood relatively unopposed by early Australian historians who did not pay much attention to the impact of the war. Scott, and to some extent Hancock, were primarily interested in the manifestation of British values and identity in the Australian people.

Michael McKernan’s The Australian people and the Great War (1980), like Scott, returned to a national focus of the home front. McKernan believed that the war was a pivotal event for the nation and he was critical of previous historians whose 'accounts neglect[ed] to show what an enormous effect the war had on the lives of ordinary Australian men and women'.[18] However, it was Bill Gammage’s The broken years (1974) that first challenged the absence of the war from the national narrative. Using the letters of men in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), Gammage combined social history with a revival of interest in Australian military history. The emphasis on the tragic and destructive nature of the war by Gammage and McKernan has been marked as an influential narrative that inspired a renewed focus on the war in the national consciousness.[19]

From the 1980s, the events of World War I (and the Gallipoli campaign in particular) became central components in the historical conceptualisation of Australian national identity. Gammage was the historical advisor for Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981), a film shown in cinemas and schools that some would argue expounded a nationalistic conception of the war.[20] Military history would grow to become a contested and emotive subject, in scholarly as well as political circles. Christina Twomey suggests that the emphasis upon 'trauma' and tragic aspects of the war were essential to changing narratives surrounding Anzac Day, which was previously made newsworthy by the presence of anti-war and anti-rape protesters.[21] This emphasis upon tragedy was not without controversy, with many conservative political commentators and some historians believing the dialogue was tied up in a 'radical-nationalist orthodoxy' which implied that Australians were the victims of British Imperialism.[22] Contemporary discussions about Australian war history, therefore, cannot be configured without consideration of the role it played in the 'history wars' in the 1990s and early 2000s. The main focus of these political and social debates revolved around the nature of colonial violence on the frontier; but another key clash of values focused on whether or not Australians should feel proud and celebrate the nation’s record at war, from the Gallipoli campaign onwards.[23]

The centenary of World War I has naturally inspired a plethora—even an excess—of scholarly as well as popular publications, many of which have continued to define the war as national experience.[24] Joan Beaumont concludes of the conflict that 'in essence, then, Australians ... emerged from the First World War in many cases more independent and self-consciously Australian but still proudly British'.[25] An examination of experiences in Melbourne during this time, and in particular the multiple conceptions of identity that were manifested and contested, provides necessary ballast to over-determined narratives of national awakening.

A focus on the city as opposed to the nation state has recently re-emerged in scholarly work, though not necessarily with regard to the experience of war in Australia. Pierre Yves-Saunier has argued that a renewed focus upon municipal governance around the world would be one effective way to 'make urban history one of the avenues to historicize globalization', a critical trajectory that has recently gained ground.[26] More particularly, studies of daily life in European cities including Berlin and Vienna have addressed aspects of the city in wartime—issues for example of broad domestic policy decisions, demographic trends, food distribution and supply—and the innovation of these exercises confirms that the body of literature on daily urban life in specific urban contexts is slim compared to the vast collective scholarship on the war at national and international scales.[27]

In Capital cities at war, Jay Winter and Jean-Louis Robert argue that more local contexts can be helpful in understanding experiences of World War I. They insist that 'the concrete, visible steps taken by Frenchmen, Germans, or Englishmen to go to war, to provision the men who joined up, and to adjust to the consequences—the human dimension of war—were almost always taken within and expressed through collective life at the local level'.[28] There is no reason why the same urban-focused study would not be worthy of examination in Australia; indeed, Australia’s physical distance from the battlefields opens up different possibilities of examining the interplay between exogenous and endogenous factors in explaining war’s cultural construction and social effects.

Kate Darian-Smith’s On the home front places the city as the central focus of a wartime social history, with a particular focus on World War II through oral history rather than municipal archives.[29] A number of regional studies have explored the war in terms of rural conditions, communities and social conflicts;[30] most recently Michael McKernan comes close to a localised focus of the impact of the war in Victoria at war: 1914–1918, the publication of which was supported by the Victorian Government 'to mark the centenary of World War I'. 'Any account of the Australian response to the war, or any part of it, must highlight the generosity of that response, the nobility of sacrifice freely embraced and the determination to endure to the end', declares McKernan. There is no doubt that there were acts of valour and sacrifice, but the claim that there was a unified and generous response can be questioned on the ground, and a more nuanced analysis of home-front experiences shows that there were complex intentions behind even some of the most seemingly noble responses to the war.[31]

Some urban histories are useful in understanding the impact of the war at a suburban level,[32] though other local-level studies concede the absence of detailed research into the impact of World War I.[33] Important elements of wartime experiences in Melbourne can be drawn from works that are not regionally focused. Maxwell Waugh’s Soldier boys looks into the experiences of school children in the leadup to and during the war, in Australia and New Zealand, with a significant focus on Melbourne.[34] Waugh is particularly concerned with the militarisation of schools as institutions, and argues that they were far more militaristic than any in the world, bar Switzerland. Another work that usefully covers individual experiences in wartime Melbourne is Elizabeth Nelson’s Homefront hostilities: the First World War and domestic violence. Nelson uncovers how the militarisation of civilians had a disturbing impact upon domestic violence in relationships, arguing that 'wartime constructions of masculinity shaped individual men’s behaviour on the home-front'.[35] In sum, there has not yet been a coherent city-based focus on the city of Melbourne during World War I. Judith Smart’s recent contribution to a special issue of the La Trobe Journal—with its particular focus on the hardening of class lines and the inflection of gender and sectarian divisions—is exemplary in suggesting that Melbourne’s response to the war was 'mixed and complex';[36] where Smart draws primarily on newspaper reports, this article takes a municipal archive as its raw material in order to illuminate a street-level view of a mass phenomenon.

A city-based view

Public life, the expression of loyalty, anti-war sentiment, the conscription debate, identification of enemy aliens, the impact of war on the economy, the effect of a wartime footing on the everyday management of the city, the visible effect of the war on council employees, and the post-war experience of returned soldiers—our understanding of many wartime processes and events can be materially enhanced through a city-based view. Many documents and letters are infused with expressions of patriotism and loyalty to Australia, Britain and the Empire.[37] David Duncan writes to the Town Clerk on 12 July 1915 that 'certain persons ... in the Botanical Reserve, Yarra Park ... South Richmond ... play football and pitch and toss ... It seems to me callous in the highest degree on the part of these young men, who indulge on Sunday ... when possibly at the same time their fellow Victorians are fighting so nobly on our behalf in the Dardanelles'.[38] The MCC was intimately involved in numerous ways: it raised money for ambulances, encouraged enlistment, and distributed recruiting posters,[39] while the growing visibility of the military in the city as the war progressed is evident in council files through discussions of marches and other war-related activities.

Militarised areas of the city served as a constant reminder that an Empire and its people were at war. The military camps at Broadmeadows, Royal Park and the Kensington Show Grounds became features of the landscape for the duration of the conflict. For civilians, prescriptions under various defence Acts meant that areas of their neighbourhoods were already used for military purposes before the outbreak of war. There is a significant amount of research on the militarisation of civilians in Australia—particularly of schoolboys—and the prevailing ideologies that motivated it.[40] The way in which these ideologies were performed in the urban environment is more of interest in the context of this article.

From 1909 all males were required to attend military drill, even during peacetime. This policy severely disadvantaged working-class men who were required to drill during their leisure time, while private school boys were able to fill their requirements as a part of their schooling. Under the Defence Act 1910 there were 27,749 prosecutions of young men not attending compulsory drill.[41] These drills occurred in designated areas mostly very central to the city of Melbourne. A map found in the collection is marked with the designated training areas and shows that Port Melbourne was the furthest site west and Box Hill the furthest east, going northwards there was no site past Carlton North. For working-class school children these designated areas of drill would have been the places of their forced and performed engagement in the conflict, reminding them of their roles as male citizens of the nation and of their responsibility to defend it when called upon.

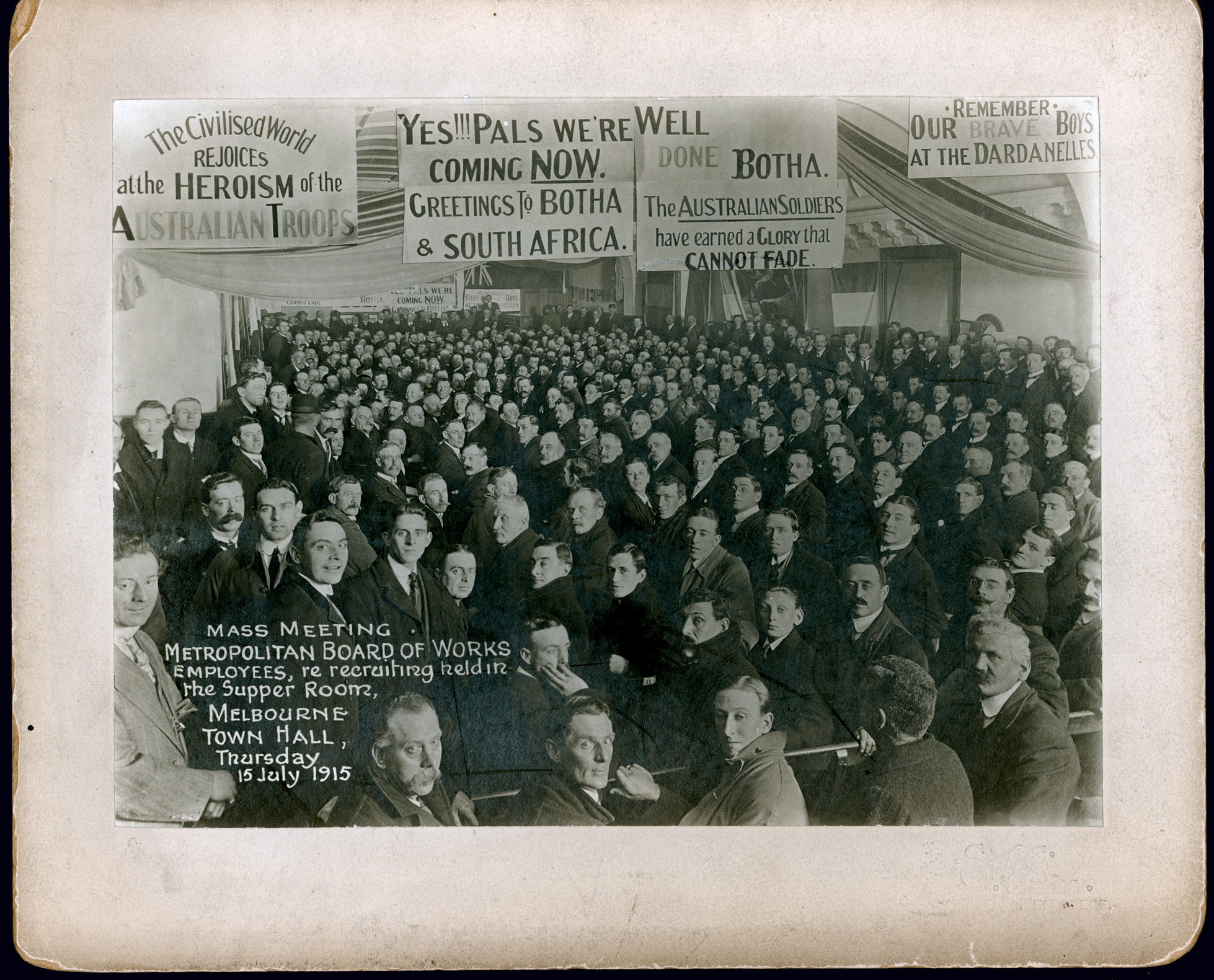

Public life in Melbourne during the war was overwhelmed by gatherings and entertainments in urban spaces both on a large and small scale. The city streets, halls, parks and other public spaces were constantly in use for events related to the war, for fundraising concerts, patriotic displays, compassionate work, enlistment drives, troops marching to war, and early Anzac Day remembrances and celebratory events at the end of the war. Public celebrations, demonstrations, gatherings, and entertainments of all sorts were a regular occurrence in the city of Melbourne prior to the war. But the war did not bring them to a halt as perhaps might be expected; rather, they were reframed into public expressions appropriate to the experience of the times and into appropriate activities that were resonant with nationalistic and imperial fervour.

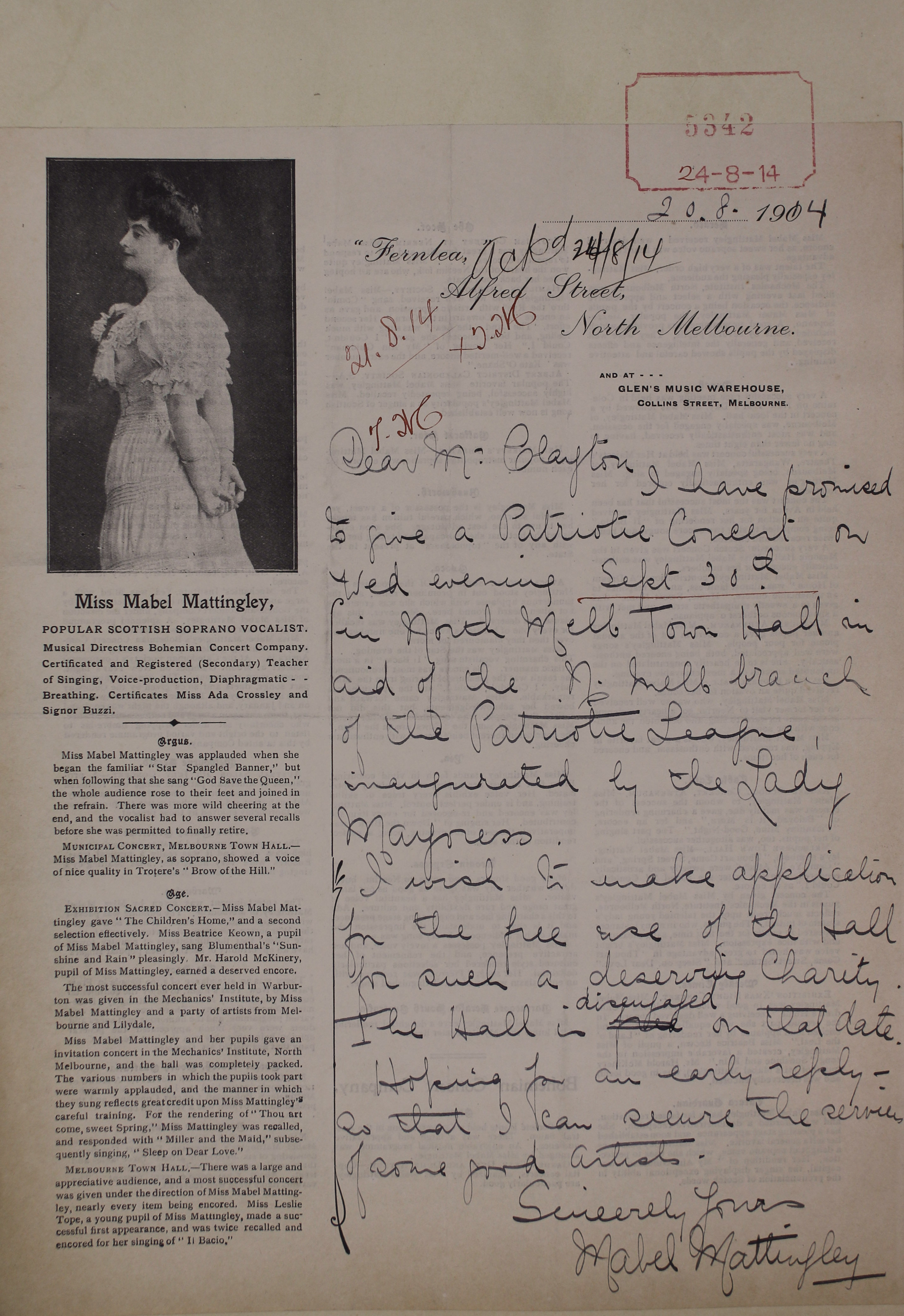

In the first few weeks and months of the war, public events and private entertainments were abandoned due to the outbreak of the conflict. On 7 August 1914, the concert by Mischa Elman was cancelled on account of the war and in order for the Town Hall to be made available for patriotic purposes, while on 13 August a parade organised by the Imperial Boy Scouts to commemorate the anniversary of the departure of explorers Burke and Wills was cancelled.[42] However, on 4 August, Mrs MC Braddy, Honourable Secretary of the Fitzroy Patriotic Committee, requested permission to hold a band performance in Fitzroy Gardens on 23 August for the Lady Mayoress’s Patriotic League Fund.[43] On Friday 11 August a lecture was held by Dr Rosenhain on 'The making of a big gun' in the Town Hall, with proceeds going to the Patriotic Fund and the Red Cross Fund. Mrs J Graham wrote requesting the use of Kensington Town Hall for a Euchre party in aid of the Patriotic Fund on 12 September.

Dozens of events are recorded, run by a diversity of groups and individuals, as permission was sought to use council properties for these purposes. Council policies encouraged the undertaking of and participation in such events, by providing refunds for the hiring costs or electric light charges[44] of municipal properties, such as town halls and park bandstands, as long as they were used for patriotic purposes and provided the balance sheets for the expenditure and income to the council upon completion of the event.[45] Later, this seems to have been restricted to the condition that the proceeds were given to the Lord Mayor or Mayoress’s Patriotic Funds—at least by the beginning of August 1916, when the Field Naturalist’s Club of Victoria was refused free use of the Melbourne Town Hall for a flower show on behalf of the YMCA soldiers’ comfort funds, unless the whole proceeds were given to the Lord Mayor’s Patriotic Fund.[46] As Smart has noted, Melbourne’s conservatives regarded compulsory military service as a civil duty rather than an infringement of civil liberty, and in the grip of the conscription debate in 1917, the City of Melbourne refused permission for anti-conscriptionists to use the Town Hall for meetings.[47] 'They could not countenance', remarks Graeme Tucker, 'the views of peace activists, unionists, socialists, and others who disagreed with the War and with conscription'.[48]

Organisations large and small, such as the Australian Red Cross and the Belgian Relief Fund, received support through these events. The year 1915 saw such a flood of such occasions, that towards the end of the year, some event organisers decided not to proceed due to the probable lack of attendance because so many events were being held. The importance of patriotic work within the daily life of the city is clearly evident and reflects the fact that around 10,000 groups were formed for patriotic purposes during the war throughout Australia, some of which used entertainments to raise money for various causes, including refugees and soldiers’ comfort funds.[49]

The outbreak of war had a consuming effect upon the social lives and activities of Melburnians. Some people expected that the outbreak of war would trigger community and national engagement. Attention to the war effort in some cases deflated the vitality of existing social activity. Enthusiasm for dancing and extravagant balls was one notable area where attitudes around socialising collided with war-mindedness. After an inability to sell tickets, one organiser of a masquerade ball unsuccessfully made a case for a refund of the use of the Kensington Town Hall. 'The public seem to have abandoned all interest in dancing', proclaimed WJ Mahon, the secretary of the Fortune Hunters Club. He made note of the wider social context, citing the fact that 'many other clubs are giving up the idea of holding their assemblies, and balls, knowing how hard it is to make things a success on account of the war'.[50] This more sombre approach is in direct contrast to other social groups who were increasing their activities. Retired military man, Frank Roy Morton, organised a ball for 23 September, inspired by the 'great patriotic feeling throughout Melbourne and suburbs'.[51] Reactions varied on a more local scale within communities that had different expectations as to what they could gain or lose from the war. Within such different social or class groups—or 'emotional communities' as Rosenwein would characterise them—there were different assessments of public sentiment;[52] it is simplistic to describe the reactions of people even within groups who supported the cause of the war as 'enthusiasm' or 'patriotism'.[53]

One of the more commonly adopted methods of expression directly related to the war can be observed in the performances of marches through the city streets. Performance and entertainment were central elements that helped draw crowds and raise money. While the broadly perceived message of participants in many of these processions was the expression of loyalty and patriotism, there were often other intended and unintended signals on display. Letting the public know who was behind the patriotic marches was a key element. 'Help make our Scotch pageantry a success', pleaded WS Lechie of the Victorian Scottish Union when asking for a permit for a march of one hundred soldiers led by a pipe band.[54] Celebrations of Scottish culture and music were already an established tradition in Victoria by this time, and an upsurge in Scottish immigration in the period 1906–1914 boosted such cultural activity and engagement.[55] Lechie’s letter is one of many examples in the Town Clerk’s records of the intention of a community to express themselves through an active gesture. In these letters, there is a planned linguistic expression that initiates an outward performance displayed before a wider public audience. The Scottish Union ultimately wanted to show its value to the Empire, but its separate ethnic identity was attributed as the reason for its loyalty and virtue. The Scottish Union displayed pride in the ethnicity of its members by supporting the British Empire in sending their sons to fight for a newly-formed army of a Dominion nation. It is therefore problematic to describe this as a purely patriotic expression, as there are multiple conceptions of identity being paraded.

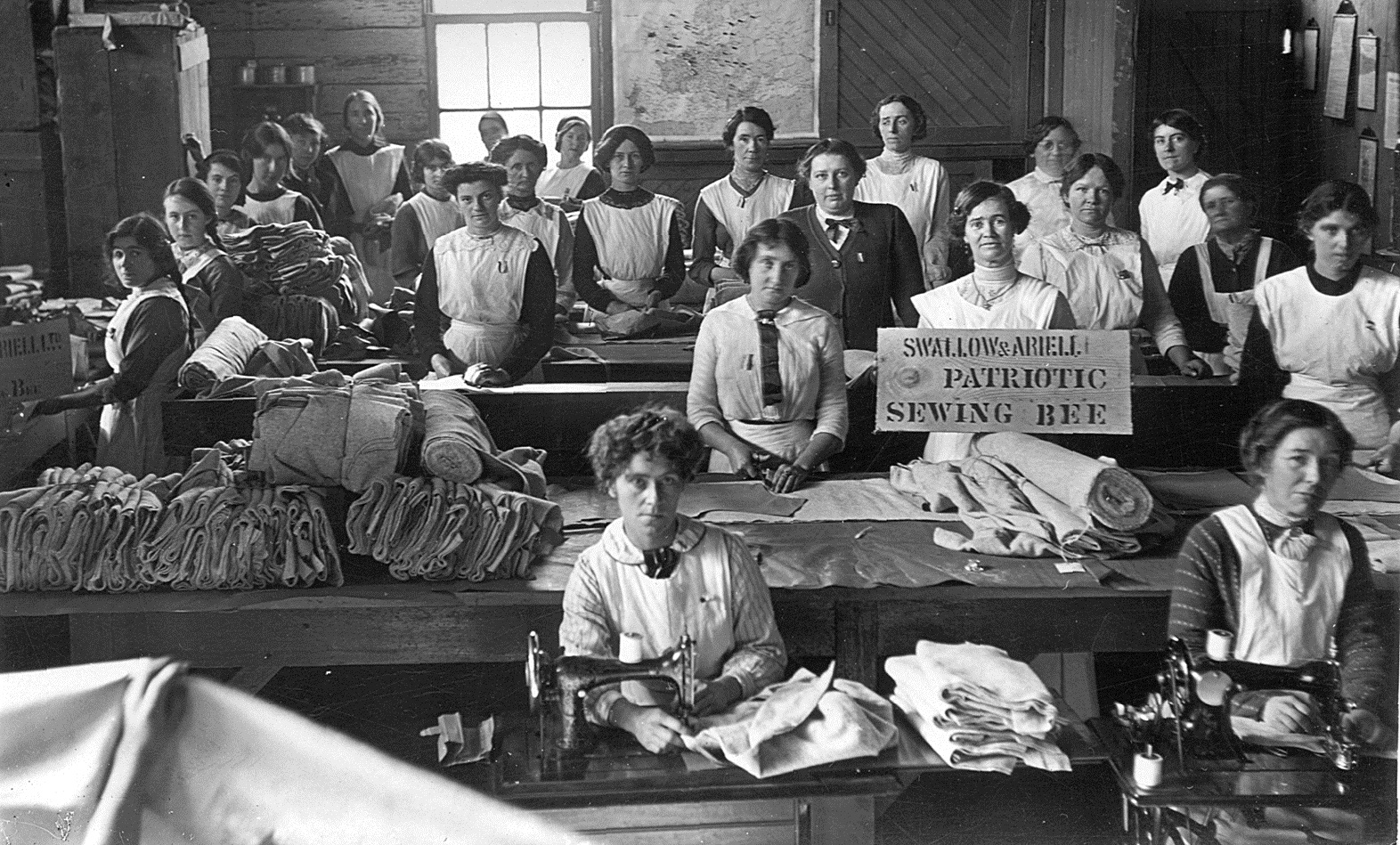

There were different expectations in Melbourne of how citizens should participate in the war that was occurring in Europe. Young men were at least expected to try to enlist as a soldier, and if they could not, the onus was often placed on them to explain why. Reasons for dismissal from military service are littered throughout the hundreds of job applications presented to the council during the war.[56] The roles of war were far less obvious and rehearsed for women, school children and non-military aged men. Particular groups and individuals took up roles of authority to inspire fortitude in their communities during uncertain times. They focused on how they could use their influence to contribute to the war or protect their people and interests from it. Private corporations, for example, often disguised their public relations efforts in patriotic displays. The MCC as a municipal authority was also expected to participate as a patriotic mobiliser. It was eager and at times pressured to use its already established authority to support initiatives such as recruitment and fundraising. It was incumbent on the council to keep in balance the realities of local governance with some of the anxieties of those who felt that civilian wartime efforts were inadequate.

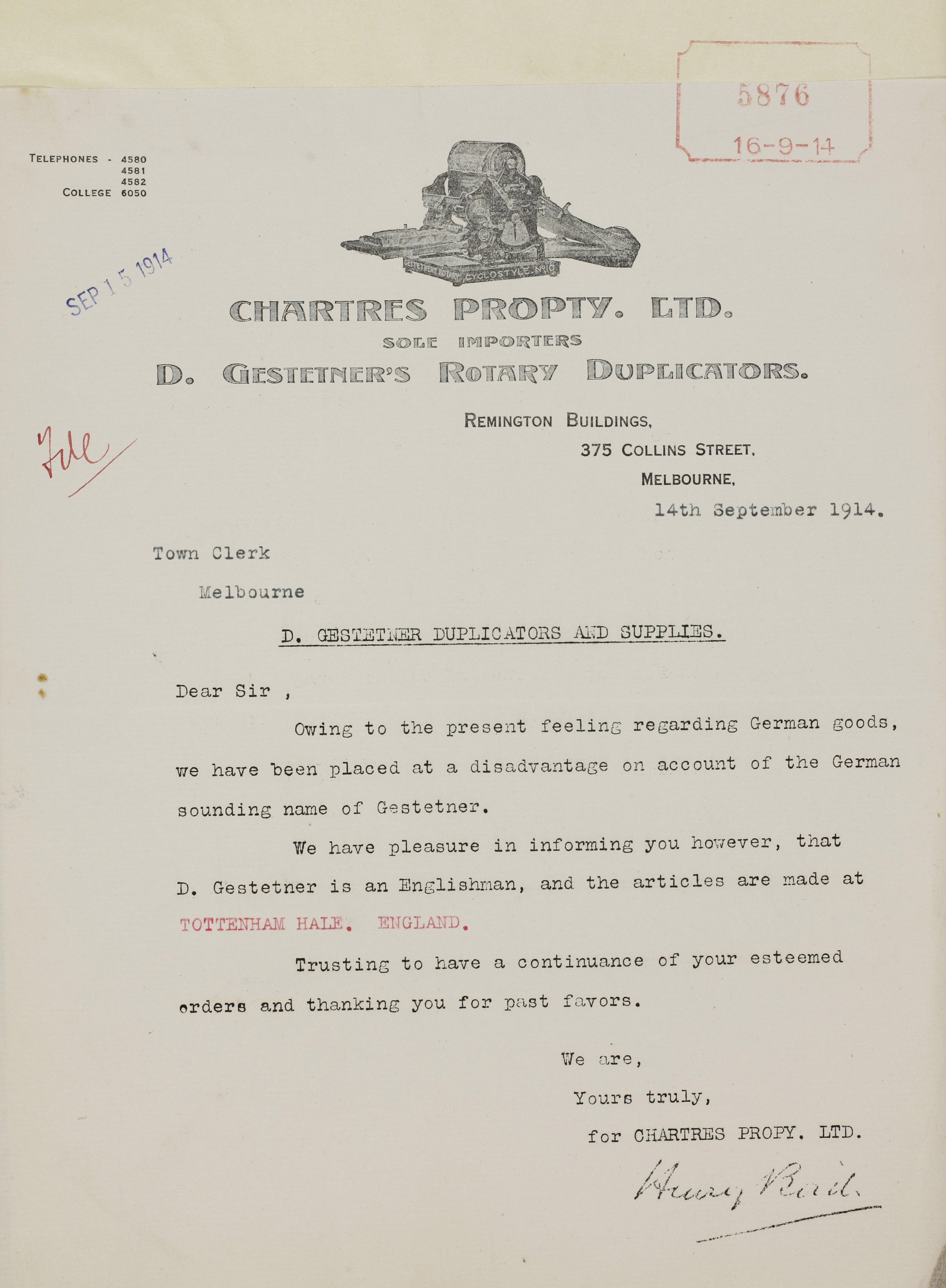

Correspondence reveals that individual loyalties—particularly of those with German-sounding names—were frequently questioned. The Recruiting Committee requested information from the MCC as to the loyalty of Ernest John Hirt, possibly due to his German-sounding name, and Frederick William Diergarten, Australian-born of German descent through his father.[57] Individuals dealing with the council were often careful to mention their ancestry—if they were German, they might state how long they or their families had been in Australia. The exclusion of German influence in economic cooperation was also implemented at all levels of government. The exuberance with which the MCC cut German ties caused confusion between companies and local and federal governments. The council cut ties with Siemens Brothers Dynamo Limited because of suspicion that the company paid dividends to enemy shareholders. The company petitioned that such a decision would hurt the 60 employees it had in Australia and the 7,000 it had in Great Britain and her other dominions. Trade and industry were geared to benefit the British Empire as an economic unit as is evident in this appeal.[58] The case was made that the dividends in question would be put into a British trust fund. To clarify this, a letter of assurance was presented to the MCC from Lord Kitchener, who was insistent on increasing war production.[59] The federal and British governments were glad that the MCC were taking seriously the German threat within, but not at the expense of compromising the production needs of the Empire to directly fight Germany and its allies outwardly.

While the MCC received orders to slow its pursuit of shutting down suspect businesses in Australia, it was also being simultaneously pressured by smaller municipal councils to do more to oppress German–Australians. John Lack has described how smaller town councils in Melbourne competed and lobbied to express their patriotic efforts.[60] The Shire of Wannon successfully lobbied the MCC to use its influence over the Victorian Government to 'secure the disenfranchisement of all enemy aliens resident in Victoria, whether naturalised or not'.[61] There were more intense calls for disenfranchisement from the press, particularly the Graphic of Australia, which sent a letter on 21 July 1916, expecting the MCC to take action to influence the removal of anyone with a German name from representative positions: 'The German element should be entirely eliminated from our public life', demanded the newspaper.[62] Their editorial 'elimination campaign' assisted in this process by publishing the names of Germans in elected positions on their front page.[63]

Economic and bureaucratic discrimination became tools for eager citizens and officials to accentuate their role in the home front experience and to 'feel that they were participating in an event imbued with grandeur', argues Fischer.[64] Victims of this type of vitriol appealed in vain to the MCC for any form of protection. In September 1914, Chartres Pty Ltd, importers of D Gestetner’s Rotary Duplicators wrote to the Town Clerk, worried about the company’s economic disadvantage because of its German-sounding name.[65] Perception of Germanic association was poison to a private company’s brand. The C & G Rubber Company, whose offices were in Collins Street, wrote a letter to its customers claiming that 'rumours' of Germanic association had led to the 'seizure of our goods, arrest of our officials, the closing of our business'. The letter was a last ditch performance of public relations in order to fend off ruin by displaying the company’s loyalty to the Empire. Such messages did not convince the press. The Age attacked the letters for being effective in deceiving customers of the company’s intentions to trade with Germany whose purpose was to 'crush and humiliate the British race'. The Town Clerk read this article passively, concerned not with the treatment of the company but the article’s false accusation that the MCC used the company’s tyres.[66] Section 5 of the War Precautions Act 1914 had introduced prohibitions and controls on enemy aliens, and anti-Germanic sentiment became a central component of the performance of loyalty. While discrimination was enacted from the top down from the Federal Government, the ability to deny prosperity and enforce exclusion in communities across the nation was a power that local governments were expected to enforce.

In some cases, the patriotic cleansing was not immediate. It took until the very end of 1915 for the closing of the Turkish Baths on Swanston Street, with the consequent loss of several local jobs. Initially the closure seemed inconsequential to the MCC on the basis of patriotic principle, although it did mean that certain vulnerable individuals such as one 16-year-old boy who had lost the ends of his fingers needed to find an alternative form of employment.[67] Here was another example of prioritising patriotism even if it went against economic and social pragmatism. Robert Wuchatsch has concluded that patriotic fervour, emotional stress caused by the loss of a relative, and individuals seeking personal financial or political gain, were the three main features of letters of complaint against Germans in Australia.[68] The Town Clerk’s correspondence is full of examples of this language and influence in action, and provides evidence as to how groups and individuals on the home front could feel a part of the wider conflict by attacking their isolated enemies armed with just a pen and paper.

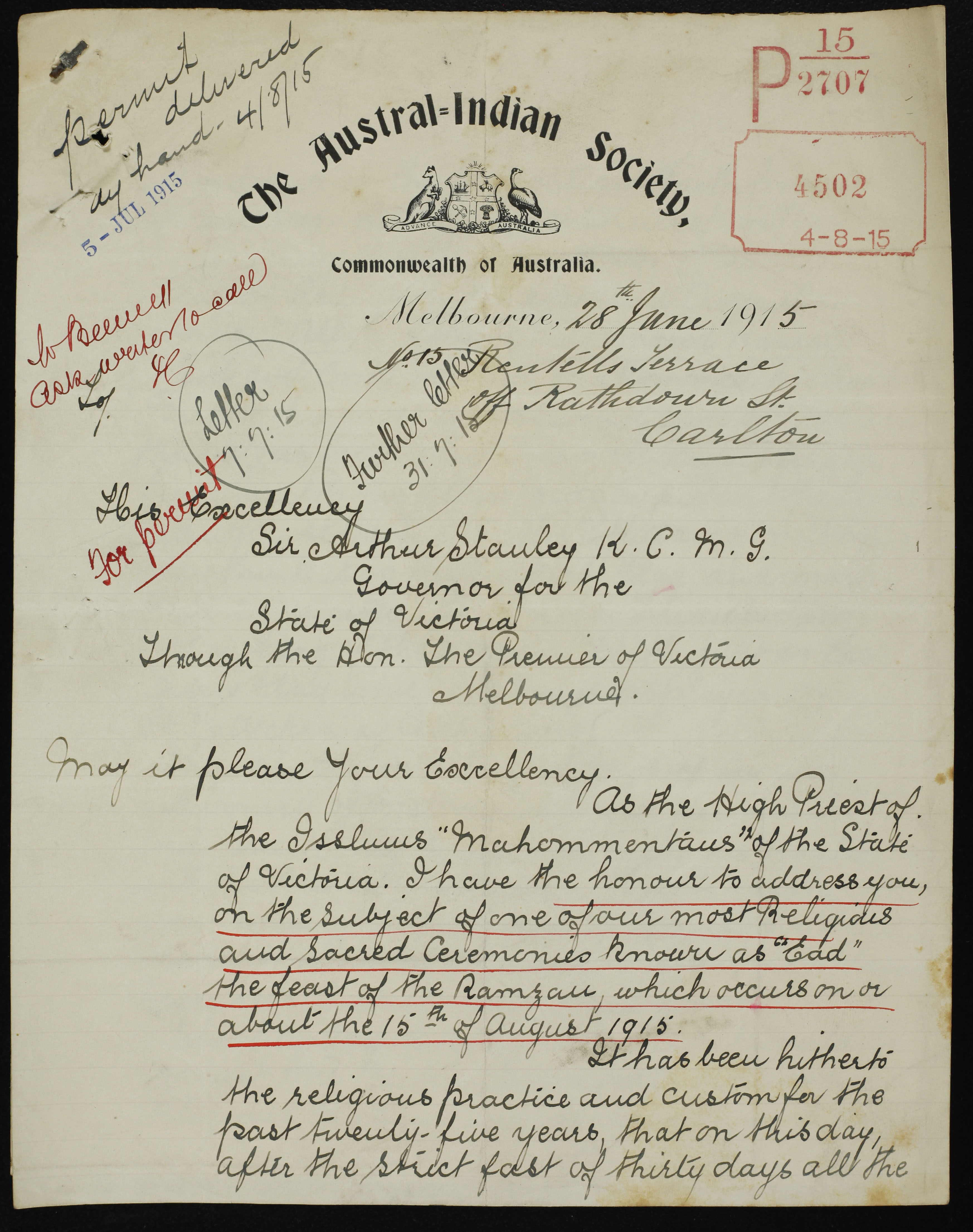

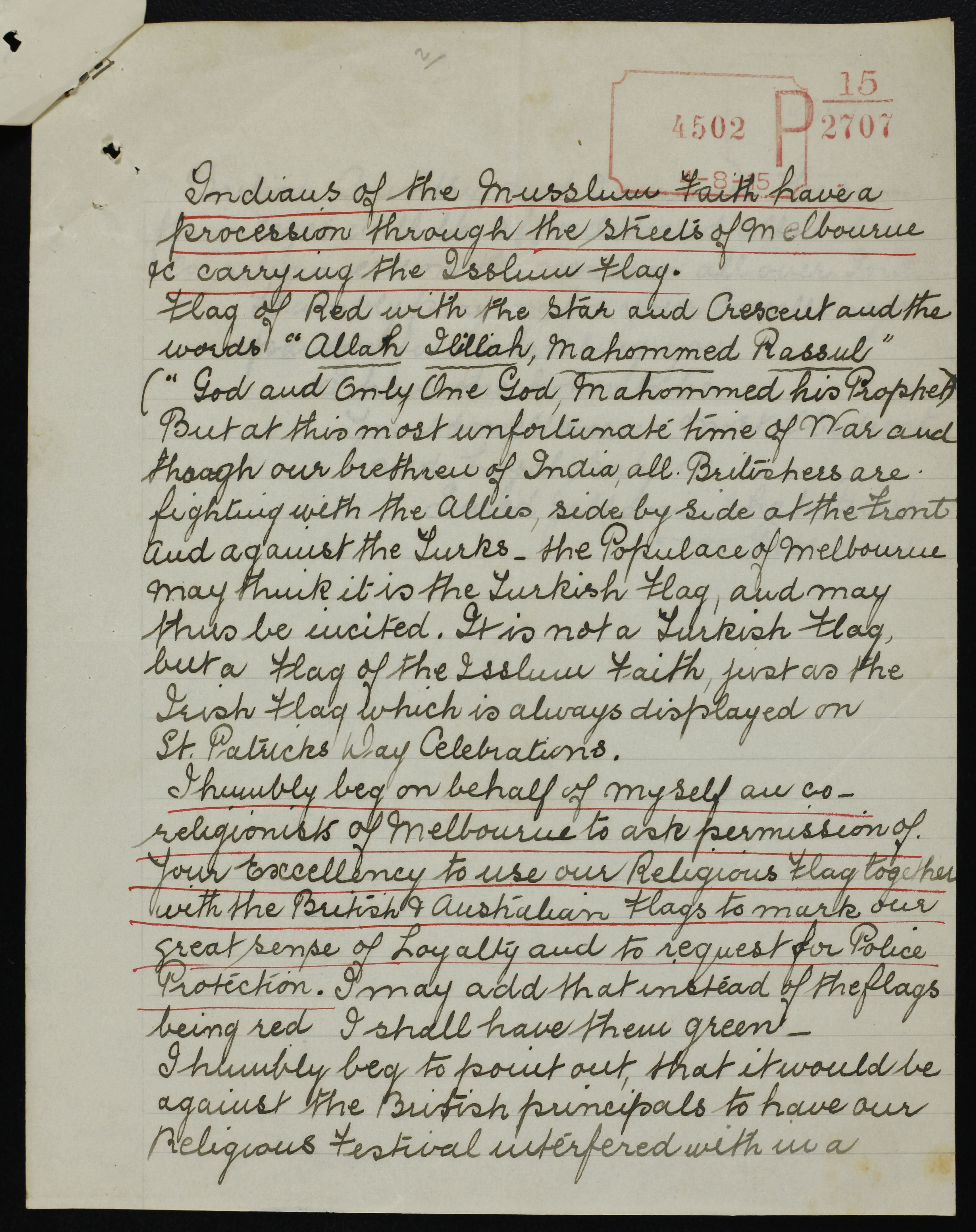

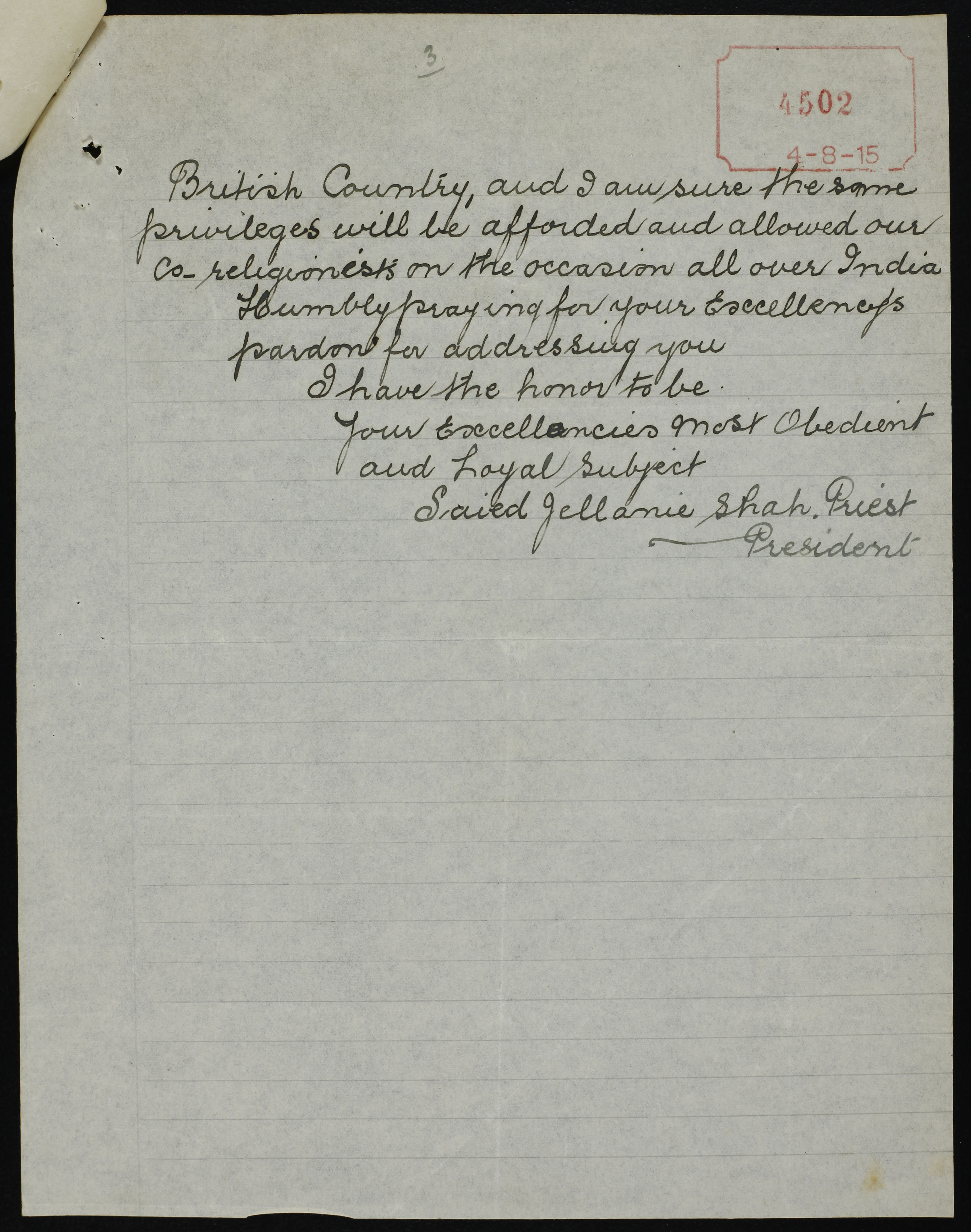

The correspondence files also reveal other complex expressions of loyalty by those of different ethnicities. The Austral–Indian Society sought permission to march for the annual Islamic religious procession for Eid, the end of Ramadan. Asserting that 'at this most unfortunate time of War and though our brethren of India all Britishers are fighting with the Allies, side by side at the Front and against the Turks', the society noted that while it usually marched under the flag of Islam, it was worried it may be mistaken for the Turkish flag. It consequently suggested marching with both the Islam flag (changed from red to green) and the Australian and British flags 'to mark our great sense of Loyalty and to request for Police Protection ... it would be against British principals [sic] to have our Religious Festival interfered with in a British Country.'[69]

Broader effects of the war can be read in correspondence mentioning the ways in which the economy was suffering from a downturn caused by both war and drought, and shopkeepers requested rate reductions in council-owned buildings due to the downturn in trade. This came after a period of buoyancy increased manufacturing and urban growth during the long recovery from the 1890s depression.[70] The running of the MCC itself was affected in myriad ways. Council employees soon requested leave to go to war, at first 'for some time', or 'until the war ends'. Many temporary jobs were thus created, and many correspondence records refer to rolling backfills and other employment-related affairs. Preference was given to those who were not eligible for service or who were returned soldiers. The need to mention the war was keenly felt in these applications (job advertisements required that they must not be eligible). Many state that they have been rejected or that they are not eligible, some say that they need to support their families, others detail their family members in the conflict.[71]

On 21 September 1914 the Legislative Committee decided that the MCC should pay employees who enlisted the difference between their service wages and the wages that they received when on service, and the council was required to keep their positions for them.[72] A review on 26 August 1916, however, determined that only men who had been employed with the council for six months should receive this benefit.

Conclusion

On 6 November 1918 the Lord Mayor of Melbourne assembled a meeting of citizens to celebrate the capitulation of the Ottoman and Austrian Empires. The German army was still intact, but Acting Prime Minister William Watt declared to the crowd that the 'coming overthrow' of Germany was only 'a question of time'.[73] Such certainty was exhilarating to the crowd in such unstable times. The armistice would come five days later, leaving the people of Melbourne to the task of the recovery of their own communities. They faced many problems, including a shortage of housing and the prospect of reintegrating soldiers back to work and health in a stagnated economy. There were many destructive elements of the war, including the conscription debates; one of the most damaging on the home front was the capacity of people to get along with each other in such trying circumstances. The war undoubtedly impacted upon people’s lives, but the ways in which people believed they should act during such times equally shaped their behaviours and relationships.

The public spaces of Melbourne became an important and contested canvas of social and emotional expression throughout the war. This article has highlighted a number of ways in which the war years can be seen less as a homogenous period in the city’s history, and more of a stage where manifestations of interest, loyalty, engagement and fear, ebbed and flowed as a consequence of the interaction between local, national and international forces and events. At times there were palpable tensions between the city being en fête for war causes, and a wartime morality that influenced those activities that were acceptable and those that were not. During the early stages of the war, social activity was tied into the mobilisation of patriotic efforts. The MCC was happy to foster this desire to contribute, as it reflected well upon the corporation as an entity under scrutiny itself, and to lead a city and culture that could be seen, despite obvious anti-war sentiment in some quarters, to be whole-heartedly contributing to the Empire’s war. When tensions surfaced among the population, performances of authority and control became a prominent method of brandishing a consensus among a divided public. The war and its pressures also forced many people to defend their emotional and political identities as citizens through a proliferation of expressive performances. The municipal records of the City of Melbourne enable a fine grained analysis of changing standards and adaptations of behaviour that are not easily reducable to simplistic labels of enthusiasm, patriotism or moral purpose. 'In wartime', Winter challenges, 'identities on all levels—that of the individual, the quartier, the city, the nation—always overlapped'.[74]f

The impact of the Great War at home has been a subject of increasing interest to scholars, particularly its impact on individual lives and communities. From public exhibitions to PhD theses, from websites to scholarly books, much of the output generated in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of World War I has engaged to some extent with the effect of the conflict on those outside the sphere of battle. For those living in Australia, thousands of miles from Europe, the war may have been physically removed but was nevertheless conceptually as tangible as if they were near the front. The archives of the City of Melbourne collection from 1914 to 1918 provide a rich source of these interactions.

The project has now digitised the documents relating to the war within the Town Clerks Correspondence with plans to make them available online under the title of The everyday war.[75] Through this medium, the collection will prove a further valuable resource for students, researchers and members of the public, with the continuing interest in World War I over the next two years and beyond. The material is already demonstrating synergies with and can add potentially valuable material to a number of projects already initiated—such as the collaboration between University of Melbourne, University of Queensland and volunteer researchers, Diggers to veterans: risk, resilience & recovery in the First AIF,[76] as well as PROV’s own Soldier Settlers research project and exhibition.[77] Likewise, with the many individual names mentioned in these records—from council workers to government officials, from business owners to everyday citizens—the collection should prove of enormous value to family history researchers who wish to know more about their specific family members and to connect these private individuals mentioned in the documents to the broader public life of the city.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 196, Item 4779.

[2] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 197, Item 4997.

[3] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 308, Item 202.

[4] Other files relating to Wardrop’s pre-enlistment military duty (in 1914), his enlistment and departure for war, and the efforts to replace him (in 1915) can be found in the collection: PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 203, Item 6027; PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 208, Item 7029; PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 244, Item 4898.

[5] The project was undertaken with a small research grant from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne, which enabled analyses and digitisation of relevant files from 1914 to 1918, from two parts of the PROV series VPRS 3183.

[6] There are subject indexes to the Town Clerk’s Correspondence Series—PROV, VPRS 8904/P1—but they have never been systematically indexed by recording metadata regarding the senders, recipients and subjects of each individual file of material.

[7] eMelbourne: the city past & present, available at <http://www.emelbourne.net.au>, accessed 16 March 2016. eMelbourne is the ongoing online iteration of Andrew Brown-May and Shurlee Swain (eds), The encyclopedia of Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2005.

[8] The project was partly inspired by and begun in loose conjunction with the University of Birmingham’s World War One Engagement Centre, Voices of War and Peace, led by Ian Grosvenor, Voices of war and peace, available at <http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org>, accessed 20 March 2016. Public Record Office Victoria provided a space and equipment to digitise the material. Our thanks to Daniel Wilksch, Coordinator, Digital Projects at PROV, who was instrumental in assisting with space and equipment onsite at the Victorian Archives Centre in order for the project to be undertaken. Thanks also to Helen Morgan, who was instrumental in getting the project online, at the University of Melbourne eScholarship Research Centre, available at <http://www.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/>, accessed 20 March 2016.

[9] Jay Winter, 'The practices of metropolitan life in wartime', in Jay Winter & Jean-Louis Robert (eds), Capital cities at war: Paris, London, Berlin, 1914–1919, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, p. 1.

[10] Andrew Brown-May, Melbourne street life: the itinerary of our days, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Kew, 1998; Andrew May & Susan Reidy, 'Town planning crusaders: urban reform in Melbourne during the progressive era', in Robert Freestone (ed.), Cities, citizens and environmental reform: histories of Australian town planning associations, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2009, pp. 89–118; Andrew Brown-May & Peg Fraser, 'Gender, respectability, and public convenience in Melbourne, Australia, 1859–1902', in Olga Gershenson & Barbara Penner (eds), Ladies and gents: public toilets and gender, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2009, pp. 75–89.

[11] Simon Purtell, 'A "souvenir of my deep interest in your future achievements": The "Melba gift" and issues of performing pitch in early 20th-Century Melbourne', Grainger Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 1, 2011, pp. 75–95; Peter Cochrane, Simpson and the donkey: the making of a legend, anniversary edition, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2013; Christina Dyson, Cultural and historical significance of Royal Park, report prepared for the City of Melbourne, September 2013.

[12] PROV Wiki, available at <http://www.wiki.prov.vic.gov.au/index.php/PROV_Wiki_-_Home>, accessed 21 March 2016; eMelbourne.

[13] Paper city, City Gallery, Town Hall Melbourne, 14 July–31 October 2011.

[14] PROV, VPRS 3183/P0, Unit 132, Defence Department letters; PROV, VPRS 3183/P0, Units 133–134, including: Stead's review (Melbourne), various issues (1917); Life Magazine (Melbourne), various issues (1916–1919); Helen Pearl Adam, International cartoons of the war, E P Dutton & Co., New York, 1916; Louis Raemaekers, Raemaeker’s cartoons, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1916; Ambrose Pratt, 'Why should we fight for England?', Australian Industrial and Mining Standard (Melbourne, 1917). On Norman Lindsay’s posters see Jelena Gvozdic, 'The legacy of wartime propaganda', Parts 1 and 2, Public Record Office Victoria Blog, available at <https://www.prov.vic.gov.au/about-us/our-blog/legacy-wartime-propaganda-part-1> and <https://www.prov.vic.gov.au/about-us/our-blog/legacy-wartime-propaganda-part-2>, accessed 8 March 2017.

[15] Curious was the absence, in 1917 and 1918, of numerous physical files. Although the numbering on extant files shows that they originally existed, there are a large number that have not been retained for those years, files relating to particular aspects of the council’s operation had been removed at some point significantly affecting our ability to analyse the material. These include very little correspondence from the Defence Department and Federal Government, job applications, prosecutions in breach of legislation and none relating to noxious trade licences, factory applications, applications for places of entertainment, suitability for the production of foodstuffs, registration of private hospitals and other types, which all reappear in 1919.

[16] WK Hancock, Australia, The Jacaranda Press, London, 1930.

[17] Ernest Scott, The official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, Vol. XI: Australia during the war, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1936.

[18] Michael McKernan, The Australian people and the Great War, Nelson, Melbourne,1980, p. 10.

[19] Bill Gammage, The broken years: Australians in the Great War, Penguin, Melbourne, 1974; Martin Crotty & Christina Spittel, 'The one day of the year and all that: Anzac between history and memory', Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 1, 2012, p. 126.

[20] James Bennett, 'Breaking out of the nationalistic paradigm: international screen texts on the 1915 Gallipoli campaign', Continuum, vol. 28, no. 5, 2014, p. 642.

[21] Christina Twomey, 'Trauma and the reinvigoration of Anzac: an argument', History Australia, vol. 10, no. 3, 2013, pp. 85–108.

[22] Frank Bongiorno & Grant Mansfield, 'Whose war was it anyway? Some Australian historians and the Great War', History Compass, vol. 6, no. 1, 2009, pp. 62–69.

[23] Andrew Bonnell & Martin Crotty, 'Australia’s history under Howard, 1996–2007', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, vol. 617, 2008, pp. 149–165.

[24] Phillip Payton, Australia in the Great War, Robert Hale Ltd, London, 2015.

[25] Joan Beaumont, '"Unitedly we have fought": imperial loyalty and the Australian war effort', International Affairs, vol. 90, no. 2, 2014, p. 399; Joan Beaumont (ed.), 'Introduction', in Australia’s war 1914–18, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, p. 995.

[26] Pierre-Yves Saunier, 'Introduction', in Pierre-Yves Saunier & Shane Ewen (eds), Another global city: historical explorations into the transnational municipal movement, 1850–2000, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2008, pp. 1–18. Brown-May’s chapter in the book is particularly relevant, as it demonstrates the importance of a renewed and localised focus on the impact of municipal governance: Andrew Brown-May, 'In the precincts of the global city: the transnational network of municipal affairs in Melbourne, Australia', pp. 19–34.

[27] See for example Belinda Davis, Home fires burning: food, politics, and everyday life in World War I Berlin, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill & London, 2000; Maureen Healy, Vienna and the fall of the Habsburg Empire: total war and everyday life in World War I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004.

[28] Winter & Robert, Capital cities at war, p. 4.

[29] Kate Darian-Smith, On the home front: Melbourne in wartime, 1939–1945, University of Melbourne Press, Carlton, 1990.

[30] J McQuilton, 'A Shire at war: Yackandandah 1914–1918', Journal of the Australian War Memorial, vol. 11, 1987, pp. 3–15; John McQuilton, Rural Australia and the Great War: from Tarrawingee to Tangambalanga, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2001. See also Raymond Evans, Loyalty and disloyalty: social conflict on the Queensland homefront, 1914–18, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1987.

[31] Michael McKernan, Victoria at war: 1914–1918, New South Publishing, Sydney, 2014, p. 4.

[32] Janet McCalman, 'War and Peace I', in Struggletown: public and private life in Richmond 1900–1965, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1985, pp. 89–119; John Lack, 'Footscray at war', in A history of Footscray, Hargreen Publishing Company, Melbourne, 1991.

[33] Peter Yule (ed.), Carlton, a history, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2004, p. xii.

[34] Maxwell N Waugh, Soldier boys: the militarisation of Australian and New Zealand schools for World War I, Melbourne Books, Melbourne, 2014.

[35] Elizabeth Nelson, Homefront hostilities: the First World War and domestic violence, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2014, pp. 41–42.

[36] Judith Smart, 'A divided national capital: Melbourne in the Great War', The La Trobe Journal, vol. 96, 2015, p. 32.

[37] Annie Woodburn, Secretary, Women’s Brigade & Battalion Depots to Town Clerk, 7 October 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 288, Item 4959: 'as our funds are depleted by the Christmas boy’s comfort’s fund & also that our cause is for Empire. We having made the greatest of all sacrifices, nay "it is a glorious privilege". We are asking to have the Hall free. ... Yours for King and Empire'.

[38] David Duncan to the Town Clerk, 12 July 1915, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 258, Item 6.

[39] Military Registrar Melbourne Sub District 44 to the Deputy Town Clerk, 1 October 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 287, Item 4737.

[40] Thomas W Tanner, Compulsory citizen soldiers, Alternative Publishing Co-Operative Limited, Waterloo, 1980; John Barrett, Falling in: Australians and ‘boy conscription' 1911–1915, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1979, pp. 2–4.

[41] Waugh, Soldier boys, p. 95.

[42] A Jerome to Town Clerk, 7 August 1914, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 198, Item 5048; Hon. Secretary Imperial Boy Scouts to Town Clerk, 13 August 1914, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 198, Item 5152.

[43] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 198, Item 5223; VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 198, Item 5228; VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 199, Item 5262.

[44] For example PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 291, Item 5406: when the Police Charity Carnival requested that the account for electric light supplied be withdrawn as proceeds were to be given to Hospital Saturday (to raise money for local hospitals), the City Electrical Engineer replied that 'it is not the practice for the Department to make concessions except for lighting for Patriotic purposes'.

[45] PROV, VPRS 3183 P/1, Unit 269, Item 1979.

[46] Town Clerk to Honourable Secretary, The Field Naturalists’ Club of Victoria, 3 August 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 291, Item 5591; The Town Clerk to Secretary, Ball & Welch Pty. Ltd., 8 December 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 291, Item 5614.

[47] Judith Smart, 'A divided national capital: Melbourne in the Great War', The La Trobe Journal, vol. 96, 2015, pp. 49, 53.

[48] Graeme Tucker, 'The Melbourne Town Hall: the City’s meeting place?', in Graeme Davison & Andrew May (eds), Melbourne centre stage: the Corporation of Melbourne 1842–1992, special issue of Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 63, nos 2 & 3, 1992, p. 40.

[49] Peter Stanley, 'Society', in John Connor, Peter Stanley & Peter Yule, The war at home, Volume IV: The centenary history of Australia and the Great War, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2015, pp. 165–169.

[50] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 201, Item 5672.

[51] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 200, Item 5525, p. 2.

[52] Barbara Rosenwein, 'Review essay: Worrying about emotions in history', American Historical Review, vol. 107, 2002, p. 842.

[53] Alida Green argues that urbanisation and the outbreak of war created a vibrant ballroom dancing culture in South Africa. Alida Green, 'The Great War and a new dance beat: opening the South African dance floor', Historia, vol. 60, no. 1, 2015, pp. 60–74.

[54] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 200, Item 5528.

[55] Malcolm D Prentis, The Scots in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2008, pp. 147,198, 210; Susan Cowan, 'Contributing Caledonian culture: a legacy of the Scottish diaspora', Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 76, 2003, pp. 87–95.

[56] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 264, Item 1138, p. 4; Nelson, Homefront hostilities.

[57] Lieutenant, OC Recruiting Depot, Town Hall to Town Clerk, 13 November 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 291, Item 5493; O.C. Recruiting Depot, Town Hall to Town Clerk, 27 November 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 293, Item 5725.

[58] For further reading on the globalised economic system of the British Empire during this time, see Mark Brayshay, Mark Cleary & John Selwood, 'Interlocking directorships and trans-national linkages within the British Empire, 1900–1930', Area, vol. 37, no. 2, 2005, pp. 209–222.

[59] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 218, Item 712, pp. 1, 17; Thomas W Tanner, 'Lord Kitchener and the consolidation of compulsion' in Compulsory citizen soldiers, Alternative Publishing Co-Operative Limited, Waterloo, 1980, pp. 163–178.

[60] Lack, A History of Footscray, p. 213.

[61] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 288, Item 4176.

[62] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 279, Item 3624, p. 4.

[63] 'Huns in public life: Graphic’s elimination campaign', Graphic of Australia, 25 August, 1916. p. 14.

[64] Gerhard Fischer, 'Fighting the war at home', The enemy at home: German internees in World War I Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2011, pp. 18–22.

[65] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 200, Item 5876, p. 2.

[66] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 207, Item 6771.

[67] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 258, Item 65, p. 2.

[68] Robert Wuchatsch, Wesgarthtown: the German settlement at Thomastown, Robert Wuchatsch, Melbourne, 1985.

[69] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 241, Item 4502.

[70] Henry F Dunne & C Mitscherlich to Town Clerk, 11 August 1914, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 198, Item 5080. Dunne, who had shops in the Eastern Market asked, 'In view of the slackness and uncertain state of trade occasioned by the present war and the serious depression which will follow, we ... would take it as a gracious and patriotic act if your committee would hold in abeyance the proposed increase of rent ...'; M Healey to Town Clerk, 25 August 1914, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 199, Item 5410, Healey asks for his Victoria Market shop rent to not be raised until the war has ended due to slackness in trade.

[71] Applications for position to the Chairman of the Public Works Committee, 12–16 October 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 289, Item 5108. In the applications for a temporary position as architectural draftsman in the City Engineer’s Office to replace the draftsman who is on active service, 'preference [was] given to returned soldiers, married men with families, men over military age and those unfit for military service'.

[72] Clerk of Disbursements to Town Clerk, 24 January 1917, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 295, Item 6014; Clerk of Disbursements to Town Clerk, 18 October 1916, PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 289, Item 5026. This did not include men called up for service by proclamation.

[73] PROV, VPRS 3183/P1, Unit 307, Item 4930, p. 13; 'The dawn of peace’, Age, 7 November 1918.

[74] Jay Winter, 'The practices of metropolitan life in wartime', in Winter & Robert (eds), Capital cities at war, p. 3.

[75] University of Melbourne, The everyday war: World War I and the City of Melbourne, available at <http://www.emelbourne.net.au/everydaywar/>, accessed 30 March 2017.

[76] Diggers to veterans: a history, Facebook page, available at <https://www.facebook.com/groups/DiggersToVeterans/>, accessed 21 March 2016.

[77] PROV, Battle to farm: WWI soldier settlement records in Victoria, available at <http://soldiersettlement.prov.vic.gov.au/>, accessed 28 April 2016; Soldier on: WW1 soldier settler stories, exhibition at Old Treasury Building, 9 November 2015 to 15 August 2016.