Last updated:

‘The Pope House, Williamstown: A Case of Adverse Possession in 1840s Melbourne’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 12, 2013. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Fay Woodhouse

The history of a derelict house in Aitken Street, Williamstown is an intriguing story of adverse possession. The Pope family, who had lived in the house since about 1842, claimed ownership by adverse possession in 1887 when they decided to sell the property. Victorian law then and now allows for the acquisition of land belonging to another person: the latest successful claim of adverse possession was in 2002, and some of the elements of proving the case are common to both stories. In 2006 the current owner of the Aitken Street property wanted to realise his asset by demolishing the house and selling the valuable land, but Hobson’s Bay Council could not grant permission until it had been established definitively when the house was built, as it already had a heritage overlay. This essay reflects on the outcome of my research to establish the date of construction and the means by which I found this information. Some of the key documents supporting the Pope family’s claim of adverse possession are held at PROV.

Background

In 2006 I was commissioned by Hobson’s Bay Council to investigate the history of a derelict house in Aitken Street, Williamstown. The house had not been occupied since the 1960s and was boarded up, falling down and covered in graffiti. It did have a local heritage overlay, however, and tourist buses drove past to show visitors the oldest house in Williamstown.[1] One block back from Nelson Place, the large parcel of land had been used as a dumping ground for contaminated 44-gallon drums, but still had enormous re-sale value. When the owner wanted to sell his valuable asset, Hobson’s Bay Council was required to establish the age of the house before permission could be granted for the building to be demolished. A previous study had not been able to establish a date of construction.[2]

After a lengthy search through deeds and memorials at Land Victoria, the research trail led me to PROV to examine a statutory declaration forming part of an 1887 claim of adverse possession of the Aitken Street property. Finding the musty old box of documents at PROV was exciting and the contents of the box contained many surprises. Ultimately, I was able to date the house’s construction to 1842, confirming that it was indeed one of the oldest timber houses built in Williamstown.[3] Willys Keeble has subsequently undertaken forensic research of the physical fabric of the building. Her investigations prove beyond doubt that it was built in the early 1840s and is a rare example of a rough sawn timber construction built with Tasmanian timber probably sawn on the site.[4] I eagerly await the publication of this research.

I have remained fascinated by the story of this house, and seven years after researching its history I have revisited the original documents. While my aim in 2006 was simply to establish the date of construction, this essay tells about the complex land title system in Victoria. When a new system of registration of land sales was introduced into the colony in 1862, vendors had to prove ownership of their land in order to convert the old title into the new Torrens system.[5] The story of ownership by adverse possession was played out when the owner of 43 Aitken Street (then Little Nelson Street) wanted to sell the property and had to prove continuous ownership for thirty years. The Pope House therefore remains an intriguing story of adverse possession which began in 1842. The last successful claim of adverse possession in Victoria was Guggenheimer v Registrar of Titles in 2002 and few of the requirements to prove a claim have changed in the past 170 years.

Early Melbourne and Williams’ Town

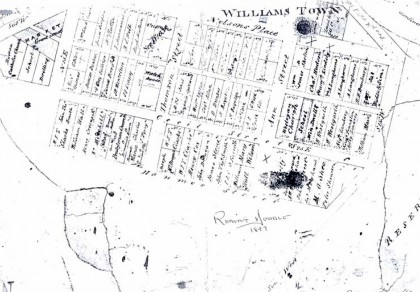

It is well documented that the city of Melbourne and the port of Williams’ Town (now Williamstown) were both surveyed in March 1837 by Robert Hoddle. Primitive conditions, wheeling and dealing and great excitement were all part of the first sale of Melbourne land on 1 June 1837.[6] The earliest maps of these districts are those drawn by Hoddle prior to the first land sales.[7] Hoddle’s 1837 plan, updated with each subsequent land sale, includes the names of purchasers of all the Williamstown allotments. Twenty years later, J Jones of the Surveyor General’s Office, Melbourne, lithographed one of the earliest surviving plans of Williamstown. Dated 20 November 1855, as well as marking the location of churches, the electric telegraph office, the watch house, Customs Reserve and the Old Pier, it also includes the names of the first owners of properties in each section of the Parish of Cut-Paw-Paw in the County of Bourke and is an excellent aid to historical research.[8] Speculators and well-known Melbourne identities who purchased land at Williams’ Town include the major landowner William JT Clarke, stockbroker JB Were, merchants Alfred Langhorne and Henry Cox, solicitor James Purves, pioneer William Westgarth, and merchant and politician Captain George Ward Cole.[9]Once it was opened for settlement in 1835, the Port Phillip District was a popular destination and in 1838 the population was 3511. From 1840 the majority of arrivals came direct from Britain, and the ‘Port Phillip boom made it the most magnetic’ of the Australian districts. By 1841 the population had risen to 20,416.[10]

Source: HV File No. 603436, Heritage Victoria.

The property at 43 Aitken Street was originally part of Williamstown allotment number 17, section number 2, sold at public auction on 5 January 1841. Facing Nelson Place between Thompson and Cole Streets, it consisted of 1 rood 36 perches. The purchaser, or Crown Grantee, was James Cain, who had arrived in Port Phillip from Launceston on the Tamar on 31 August 1840.[11] Cain paid the sum of two hundred pounds sterling for the land.[12] We know that Cain was a merchant, born in London in 1803 and that prior to his departure for Australia he was an associate of the merchant Robert Brooks of St Peter’s Chambers, Cornhill, London.[13] Information gleaned from the contemporary diary of Georgiana McCrae, newspaper articles, births, deaths and marriages records, the deeds and memorials found at Land Victoria, and Cain’s will, reveal that he had arrived in Melbourne alone and a widower. His two sons, James William (born 1830) and George (born 1835) remained in England until 1846.

Cain first found accommodation in Collins Street, where one of his neighbours was Captain George Ward Cole who had arrived from Sydney in July 1840.[14] The meeting was probably advantageous to Cain, as Ward had also set himself up as a merchant in Melbourne. Cain quickly began to advertise, selling tea chests and half chests, tobacco, ‘Negrohead, Colonial Brandy and Rum’ in hogsheads, Port and Sherry in hogsheads and cases, ‘Sheet, lead, loaf sugar, Mauritius loaf sugar, hay, oats and flour’.[15] Subsequent advertisements indicate he sold schooners and other naval equipment as well as wine and general merchandise. By 1842 Cain had become a Justice of the Peace. His name appears on the Melbourne Electoral Role twice in 1847 at both his residence in Bourke Lane and at a freehold residence in Flinders Street, close to Queen’s Wharf, one of his business addresses.

The Marriage of James Cain and Jane Williamson

Four years after arriving in Melbourne, on 14 November 1844 James Cain married Jane Williamson, the daughter of James and Isabella Williamson, pastoralists of Edinburgh and ‘Viewbank’, Heidelberg. ‘Viewbank’, named after a Scottish property, was built in 1839 and was one of the first grand homesteads on part of a large 1830s pastoral holding at the confluence of the Yarra and Plenty rivers on the outskirts of Melbourne.[16] The marriage took place at St James Church of England, then located on the corner of King and Collins Streets.[17] The artist and diarist, Georgiana McCrae, noted in her diary that when solicitor James Graham dined with the McCraes that evening, he commented that he had seen Captain Cain and Miss Williamson’s wedding party ‘going to the church this forenoon’.[18] James and Jane had two children, Isabella Jane (born 1846 and named after Jane’s mother) and Hannah La Protier (born 1847).[19]

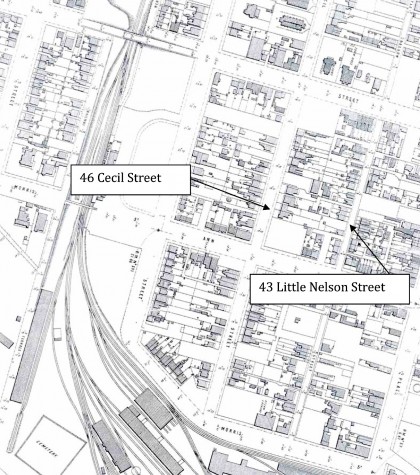

Cain’s business prospered in Melbourne and, serving the pastoral industry as a merchant, it made sense for him to own warehousing in Geelong and Melbourne. From 1846, all of Cain’s property transactions were linked to Elizabeth Miles, the grandmother of his two sons who had brought the boys with her to Melbourne. He provided for her, ‘in gratitude for care and affection bestowed … upon his sons James William and George Cain’ because, having emigrated to Australia, she had been ‘obliged to relinquish a certain annuity’ when she left England. Her interest in the properties included collecting all the rents until her death, when they passed to James William and George.[20] In 1847 Robert Towns purchased two properties from Cain, one in Williamstown and one in Corio for the sum of ₤450.[21] This purchase divided the original Williamstown property of 1 rood 36 perches into two equal size blocks. One became the property at 46 Cecil Street, Williamstown and the outline of a large Victorian house is visible on the 1855 Plan of Williamstown.

Source: University of Melbourne.

The Sudden Death of James Cain

On 27 January 1848, Cain celebrated the arrival from London and the launching of his new clipper, the Jane Cain, named after his wife. Georgiana McCrae noted that the brig was launched ‘in the presence of six thousand people’.[22] This fine beginning to the year was shattered when James Cain died, probably suddenly, on 27 June 1848 at the age of 45. It was widely reported that Cain had died ‘on Tuesday afternoon at five o’clock’and that his death was ‘deeply regretted by a numerous circle of friends’.[23]On the day of his funeral, Mr Charles Smith of Little Collins Street West invited his friends to ‘meet at three for half-past three in this day, to accompany his remains from the residence of Mr Charles Smith … to their last resting place’.[24] A few days later the Port Phillip gazette provided more detail of his demise:

THE LATE CAPTAIN CAIN – The remains of this gentleman were conveyed to their final resting place on Thursday last, and we have to mourn the departure of one whose enterprising spirit would have prompted the development of colonial resources, whilst from his great experience there could have been little fear of his judgment erring in the means adopted to attain that end. The Jane Cain, a splendid instance of the enterprise to which we have referred, in which the deceased gentleman had contemplated paying a visit to his native land, will in all probability sail for her destination in about a week from this date; some little difficulty has, we believe, arisen in consequence of the unfortunate deceased being the only party thoroughly acquainted with what cargo was actually on board the vessel, but a particular clause introduced on the bills of lading signed by the Captain has we believe remedied the difficulty.[25]

While the newspapers failed to state the cause of death, this notice is nevertheless informative. That Cain had not fully conveyed the details of the cargo to anyone may suggest his death was sudden. It may have been coincidental that his last will and testament was written only two months prior to his death. Alternatively it might suggest he was ill when he wrote his will.[26] We will never know.

In his will dated 3 May 1848, Cain bequeathed to Jane ‘the clear annual sum of one hundred and fifty pounds by equal quarterly payments’, even if she remarried. A sum was held in trust for his daughters, Isabella and Hannah, ‘and any future born child’. Probate was granted to his executors Robert Brooks, Charles Smith and Jane Cain on 22 July 1848. The executors declared that his property and effects did not exceed the value of £8,000.[27] Jane Cain did not remarry; she died as Jane Cain at the age of 69 in 1879.[28] Of Cain’s sons, James William died in Melbourne, aged 20, on 28 April 1850. George Cain attained the age of 21 on 22 February 1855, and while Elizabeth Miles still legally owned the properties he inherited, George was involved in the later subdivision of the Williamstown land.

Unravelling the Mysteries of Land Titles in Victoria

Diverting our attention now from the late James Cain, we must consider the complex legal system of land registration in nineteenth-century Victoria. There are still two systems of title in Victoria: the old (General Law) system and the current Torrens System. The former and current systems of property titles, then and now, allow for claims of adverse possession – a situation arising from the uninterrupted occupation of property belonging to someone else.

Old (General Law) System

Until 1862 when the Real Property Act came into effect, the principles of conveyancing in Victoria were the same as those used in England at the time. Under this system all land granted (that is, alienated from the Crown) was initially conveyed by means of a Crown grant in the form of a deed. Subsequent transactions (such as transfers, mortgages, leases or other dealings) were recorded by the creation of further deeds or memorials. Proof of title consisted of all documents relating to past transactions concerning the land. When selling land, a vendor must be able to trace an unbroken chain of dealings containing a deed at least thirty years old. This deed must be one which purports to deal with the whole legal and equitable interest in the land, for example conveyance of the fee simple or a first mortgage. One problem which arose from the use of this system was the existence of informal dealings for which no records were kept.

The historic documentation of early Crown grants is contained in bound volumes (known as memorials) and records of dealings in the Registrar-General’s office, now part of the Department of Sustainability and Environment. These documents must be consulted to trace the current Torrens title back to its original source. This was the methodology I used when investigating the history of 43 Aitken Street, Williamstown.

The Torrens System

Robert Richard Torrens (1814–1884), the Collector of Customs, and later Registrar-General of South Australia, devised the Torrens System of land sale.[29] Torrens introduced his system into South Australia through the Real Property Act 1857; it was enacted in Victoria under the Real Property Act of 1862 and subsequently introduced into other Australian colonies. The Torrens System recorded land ownership on a public register which detailed when the land was first sold by the Crown and listed all subsequent owners. This replaced the General Law System which relied on the execution of deeds and required individuals to prove ownership.[30]

So, from 1862 to the present, proof of title derived from early deeds can be confirmed by consulting the documentation relating to each current (Torrens) certificate of title and through searching the old General Law System of deeds and memorials contained in register books held at the Titles Office, Land Victoria. As indicated, documentary evidence used to the date the property at 43 Aitken Street included a series of deeds and memorials (from the old General Law System), current titles (volume and folio), and statutory declarations and annexures supporting a claim of adverse possession.[31]

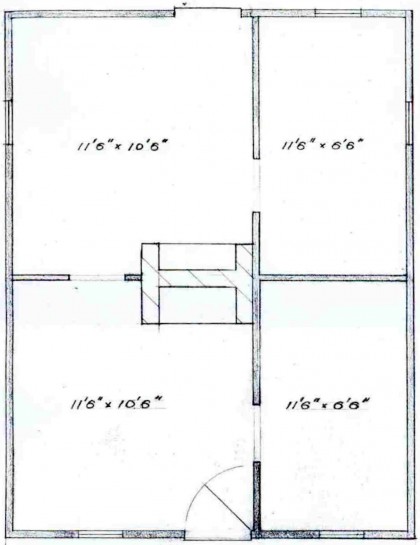

Floor Plan to 43 Aitken Street in Blunden, Salter & Winikoff, ‘Domestic Building in Williamstown before 1870’, History 4 thesis, 1964, Department of Building and Architecture, University of Melbourne, p. 28.

The First Occupier, William Pope, Shipwright, 1842

As Melbourne grew in the late 1830s, a step toward better administration occurred with the establishment of one of the first civic authorities, the Melbourne Town Hall, in 1842. However, few funds were available because of the economic depression that descended upon Australia at this time. Unemployment was high, and was made worse by the continued arrival of immigrants. Poverty and hunger were partly alleviated by the establishment of charitable institutions, but land prices slumped, commercial enterprises collapsed, and many firms and individuals wound up in the Insolvency Court. At the same time, Melbourne’s settlement was spreading and small villages were springing up around the central city. Richmond, Melbourne’s first suburb, emerged at this time. The most important ‘suburb’ was Williamstown, which had ‘about one hundred buildings, including two hotels, [and] ten mercantile stores’.[32] It also had a small pier for ships, and a lighthouse. The offices of the harbour master, boarding and customs officer, and the pilots of the port and river provided work for many men who moved to Williamstown.

Following the establishment of the Melbourne Town Hall, a revised list of electors for the Electoral District of Port Phillip, in the County of Bourke, and in the Police District of Melbourne, was published in the Port Phillip gazette on 31 May 1843. On that list William Pope, who appears as the owner of a ‘dwelling house, Williams Town’, was one of twenty-five persons on the electoral roll residing in Williamstown.[33] At the time of our story, the population of Williamstown was approximately 400 residents.[34] Ownership of a property meant Pope could vote in Melbourne’s Town Council elections. The individuals named in the list of electors in 1843 were either owners of ‘freehold’ land or a ‘dwelling house’. How did Pope prove ownership of the land he was probably squatting on?

As the registered owner of a dwelling house, from 1843 William Pope was ‘regarded as the owner’ of the land.[35] Williamstown became a municipal district in 1856, and from this date rate books recorded owners and occupiers of every residence and piece of land. When Pope died, his widow, Mrs Clara Pope, was recognised as the owner and occupier of the property at 43 Little Nelson Street.[36] Sands & Kenny’s Commercial and general Melbourne directory was first published in 1857, and Mrs Pope is found at this address. Based on the rate books and Directories, the 1990 (revised 1993) conservation study by Stearns, Butler and McBriar concluded that the house dated from 1856 (although it looked older) and that the first resident was Mrs Clara Pope.[37]

Searches in the Victorian births, deaths and marriages registers failed to reveal any registration of William Pope’s death. In his last will and testament dated 8 September 1850 (which was declared invalid because it was only witnessed by one person), William Pope declared himself ‘in full possession of my intellect’ but ‘decayed in bodily health’.[38] Pope bequeathed ‘my house and premises in which I now reside’ to his wife for the term of her natural life and, after her decease, to his sons William and Thomas. Along with bequeathing her all his ‘goods, chattels, working tools, furniture and moveables’ he allowed his wife ‘to let the said premises on lease (should she think fit) for a term not exceeding seven years’.[39] This was, in fact, what Clara Pope did during her lifetime. When she died in 1877, her son Thomas became the owner and sometime occupier of the property – he, too, let the property to tenants. However, for an undisclosed reason, even though he resided there for many years, he gave up his interest in the property, and his brother William became the sole proprietor.

The proposition that James Cain sold part of his land to William Pope in 1842 and did not register it has always been an intriguing one. It is hard to believe that the merchant and businessman, James Cain, would not have registered a sale of part of his Williamstown land – a practice he adhered to for other land purchased in the eight years he lived in Melbourne. If the ‘sale note’ for part of allotment 17 section 2 at Williamstown is genuine (see below), it was not registered with the Department of Lands and Survey under the old General Law System and therefore deeds and memorials do not exist. In 1842, if Cain had sold the land to Pope it would have been defined as ‘an informal dealing’ on the property. It was possible to acquire an estate in fee simple without registration because it was not compulsory, but it was a prudent course of action to do so.[40] Is it coincidental that this ‘sale note’ is dated 15 May 1842 and that exactly one year later, in mid-May 1843, Pope’s name appears on the list of electors? I propose that Pope used the ‘sale note’ dated ’15 May 1842′ to prove purchase of the land in Little Nelson Street, and that he had already constructed a house on the property.

The Successful Claim of Adverse Possession 1887

Because a sale of land between Cain and Pope was not registered, when he wanted to sell his property William Pope junior had to submit an Application to bring land under the operation of the ‘Transfer of Land Statute’. A claim of adverse possession meant that Pope had to prove his family’s long-standing occupation of the property. He did this by filing such a claim.

Three long-term residents of Williamstown, men who had known Pope’s father from the 1840s or 1850s, William Stone (the purchaser), William Hall and Thomas Mason, all made statutory declarations to support Pope’s claim. Together they verified the Pope family’s long-term occupation.[41]

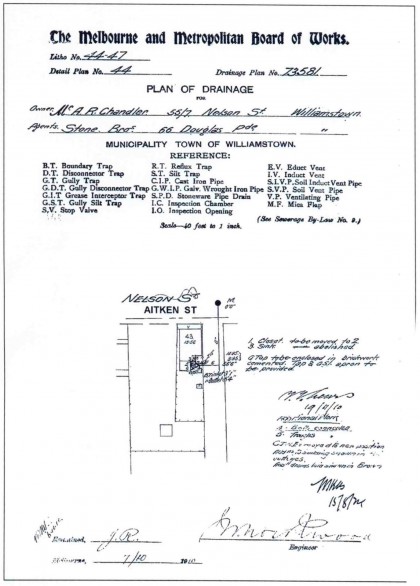

Source: Casey Inspection Service.

William Pope’s statutory declaration dated 21 February 1887 states that ‘on or about 15 May 1842’ his late father, William Pope, purchased a piece of land from Captain Cain. A ‘sale note’, he claimed, was found amongst his father’s papers and is attached to his statutory declaration as Annexe A.It is clear the ‘sale note’ is very old, the paper is very thin, the writing on the document is very faint, and some words are incomplete or abbreviated. It reads:

Bought of Capt’n Caine a piece of ground on the 15 of May 1842

23 feet of frontage x 96 feet back at Wms Town on Nelson Street in the County of Bourke the front of the ouse bearing north by the mid part of the ouse bearing S at S by East

For the sum of £50-0-0.[42]

The measurements of the land described correspond fairly accurately to the certificate of title. Reference to ‘the front of the ouse bearing north’ indicates that the house had already been constructed in 1842, the year of purchase. This supports further statutory declarations that the house and fences were built by William Pope. Did Pope build the house on the perimeter of Cain’s land before Cain was aware of it during the Depression, and, when it was discovered, did Pope made an offer to purchase the land? Annexe B is a ‘receipt’ from James Cain to William Pope for ‘the sum of twenty one pounds account of his agreement’ dated 23 October 1843.[43] This could have been anything, but the two documents were pinned together in the file when I first found them, making it look as if Pope paid Cain £20 of the £50 he owed him for the ‘sale’ of his land. Annexe C is the ‘Last Will & Testament of William Pope’ dated 8 September 1850 and another doubtful document.[44] As mentioned, a death certificate was not found, so it is unclear exactly when Pope died. Thomas Mason and William Hall both claim to have known Pope since 1844 and 1845 respectively. Although Hall declared that Pope died in 1846 or 1847, a will written in 1850 is inconsistent with this date. It is worth noting here that William Pope junior does not shed any light on the year his father died.

The three statutory declarations by Pope’s friends are all written more than thirty years after his death and forty years after his acquisition and supposed purchase of the land and construction of the house. William Hall of The Strand Williamstown, a shipwright like Pope senior, states that he had been ‘well acquainted with William Pope since 1845’ and that

He was then residing in a house erected on part of Crown Allot. 7 [sic] Sec. 1 [sic] Little Nelson Street. The house and fences were erected by said William Pope who was regarded as the Owner. Declared has resided in Williamstown since 1845 and the house and fences are in the same position now as then. [underlining in original]

William Pope died about 1846 or 1847 and declarant attended his funeral. Declarant has no interest in the application.[45]

The glaring error in this statement is that the allotment and section number are incorrect (it was Crown allotment 17 and section 2), which led to problems for Pope a few months later. Nevertheless, Hall’s statement that the house and fences were standing in 1845 when he first arrived in Williamstown supports William Pope’s argument that his father occupied the land and house in 1842.

The second friend, Thomas Mason, states that he had resided in Williamstown since 1844, that he knew William Pope who was residing in Little Nelson Street on the land that was the subject of the application, and that ‘such house was built by the said William Pope’.[46]

Finally, the purchaser of the house and land, the builder William Stone of Osborne Street Williamstown, stated that he had lived in Williamstown since 1854 and that he had known Mrs Clara Pope since 1858, having resided on an adjoining allotment. Of Mrs Pope, Stone stated that ‘She was always reported to be the owner of the house and land she occupied’ and Stone himself ‘frequently did repairs to the house for her’.[47]

To prove adverse possession in 1887, a period of thirty years of occupation had to be established. Perhaps he was not aware of it, but one important piece of evidence was not included in William Pope’s application: his father had become a registered property owner in May 1843 and was entitled to vote. Pope did submit a rate notice dated 1862 which proved his mother lived there at the time. The only other evidence used was the ‘sale note’, ‘receipt’ and last will and testament (albeit invalid). With these documents Pope successfully argued that the ‘period of continuous possession by his Father, Mother and himself covered 44 years’.[48] That is, that his family had been in possession of the land from circa May 1842 (or at the latest 1843) to February 1887. In lodging a claim of adverse possession, I propose that William Pope junior knew that the land on which his father built the family home had been acquired illegally in 1842.

Conclusion

Whether owing to James Cain’s neglect of his land or his own audacity, William Pope acquired the land in Little Nelson Street by some means in about 1842. If a sale actually took place, it was not registered and was never converted into a legal title. It is clear the house was constructed by 1843 because Pope, as noted above, was listed as one of the electors of the Port Phillip District. His widow, Clara Pope, was listed in the rate books as the owner and occupier of the house and land. Pope had built fences around the house and paid his rates since 1856, clearly taking possession of the land, either informally or illicitly. The judge presiding accepted that there was sufficient evidence that the Pope family had occupied the land in Little Nelson Street since around 1842, and William Pope’s claim of ownership by adverse possession was granted in 1887.[49]

On the most recent claim of adverse possession, Her Honour, Judge Balmford ruled that for a continuous period of fifteen years the Guggenheimer family had possessed the subject land from the person or persons who had a right to recover that land. They had enclosed the land and paid rates on it since 1980, necessary prerequisites to claim adverse possession. However, she also ruled that ‘While Mr Guggenheimer’s history does not give confidence in his credibility, his evidence was not challenged…’.[50] If Pope’s claim was submitted today, would a similar judgement of his credibility have been made?

Endnotes

[1] Hobson’s Bay City Council’s Heritage Online dates construction of the house as ‘prior to 1857’.

[2] Kinhill Stearns in association with G Butler and M McBriar, City of Williamstown conservation study, revised edn by D Hackworth, City of Williamstown, 1993, pp. 24–5. At the time of writing, the property is listed for auction on 12 October 2013.

[3] The Victorian Heritage Database also lists the property with the date ‘built prior to 1857’. See, however, ‘Our oldest house? Demolisher’s delight’, The Age, online edition, 23 April 2009, which gives the correct date of construction as c. 1842.

[4] W Keeble, personal conversation with the author, 18 February 2013.

[5] See P Cabena et al., The lands manual: a finding guide to Victorian lands records 1836–1983, 2nd edn, Royal Historical Society of Victoria, Melbourne, 1992, pp. 68–9.

[6] D Garden, Victoria, a history, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1984, pp. 34–6.

[7] The sale was advertised in the New South Wales Government gazette and the Sydney gazette: see WH Elsum, The history of Williamstown from its first settlement to a city, 1834–1934, facsimile edn, Williamstown City Council, 1985, p. 10.

[8] See Robert Hoddle’s 1837 plans at the State Library of Victoria (MAPS M 821.09 A 1837-56 HODDLE) and Plan of Williamstown, County of Bourke, Parish of Cut Paw Paw, Surveyor General’s Office, Melbourne, 20 November 1855 (State Library of Victoria, available online. There is also an amended version dated 1864 at Land Victoria.

[9] In addition to the plans of Hoddle and Jones, I also consulted the Plan, Williamstown: shewing streets at present formed or in progress of formation, drawn by A Jackson, Survey Office, Williamstown, 186-? (State Library of Victoria, MAPS X 821.08 Williamstown 186-?).

[10] Garden, p. 37.

[11] ‘Cain (Capt), Tamar, (from Launceston) 31 August 1840′, in A Romanov-Hughes (comp.), Coastal passengers to Port Phillip 1839–1845, Taradale, Victoria, c.1995 (microfiche).

[12] Land Victoria, Document No. 4795, ‘Cut Paw Paw Shire of Wmstown Allot. 17 Sec. 2, Grantee James Cain of Melb. 36 ps ₤200 5 Jan. 41, Lot 8 p. 1168′ and Town Purchase No. 11, p. 64, Grantee James Cain, dated 5 January 1841.

[13] Brooks was also a friend and an executor of his will.

[14] W Bate, ‘Cole, George Ward (1793–1879)’, Australian dictionary of biography, vol. 1, Melbourne University Press, 1966.

[15] Port Phillip gazette, 9 September 1840, p. 1.

[16] ‘Viewbank’, VHR Register No. H1396, File No. 501981: see Victorian Heritage Database.

[17] Pioneer index, Victoria 1836–1888: index to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, 3rd rev. edn, 1999 (CD-ROM).

[18] Georgiana’s journal: Melbourne 1841–1865, edited by H McCrae, 3rd edn, William Brooks, Sydney, 1978, p. 159.

[19] Pioneer index.

[20] Land Victoria, Examiners Notes, Application 4795b.

[21] Land Victoria, Application No. 54793.

[22] Georgiana’s journal, p. 157; Port Phillip gazette, 29 January 1848, p. 3.

[23] ‘Died’, Melbourne observer, 29 June 1848, p. 120. See also Port Phillip patriot, 29 June 1848, p. 6; Port Phillip herald, 29 June 1848, p. 1.

[24] Port Phillip herald, 29 June 1848, p. 3.

[25] Port Phillip gazette, 1 July 1848, p. 2; reprinted in the Geelong advertiser, 4 July 1848, p. 2.

[26] PROV, VPRS 7592/P1 Wills and Probate and Administration Files, Unit 2, File A/215.

[27] PROV, VPRS28/P0, Probate and Administration Files, Unit 3, File A/215.

[28] Pioneer index.

[29] H Doyle, ‘Torrens title’, in Oxford companion to Australian history, ed. G Davison et al., revised edition, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001, p. 643. Torrens was a supporter of the Wakefield system of colonisation and land settlement: see H Doyle, ‘Wakefield system’, in ibid., p. 668.

[30] Cabena et al., The lands manual, pp. 68–9; Doyle, ‘Torrens title’.

[31] Land Victoria, Certificate of Title vol. 2821, fol. 051 and Certificate of Title vol. 9254, fol. 562.

[32] Garden, pp. 45–6.

[33] ‘Electors for the District of Port Phillip’, Port Phillip gazette, 31 May 1843, p. 1.

[34] Garden, p. 46.

[35] PROV, VA 862 Office of the Registrar-General and the Office of Titles, VPRS 460/P0 Applications for Certificates of Title, Unit 2173, Statutory Declaration 17656, William Pope [junior], 21 February 1887, Search Certificate No. 22584 in relation to Application No. 32617, p. 1.

[36] PROV, VA 2535 Williamstown, VPRS 2132/P0 Rate Books, Unit 1 1864–1865.

[37] City of Williamstown conservation study.

[38] PROV, VPRS 460/P0, Unit 2173, Annexe C to Statutory Declaration 17656.

[39] ibid.

[40] F Burns, ‘Adverse possession and title-by-registration systems in Australia and England’, Melbourne University law review, vol. 35, 2011, footnote 88, p. 785.

[41] PROV, VPRS 460/P0, Unit 2173, Statutory Declarations 17656 (21 February 1887), 18931 (24 March 1887), 19838 (14 April 1887) and 20796 (11 May 1887).

[42] ibid., Annexe A to Statutory Declaration 17656.

[43] ibid., Annexe B to Statutory Declaration 17656.

[44] ibid., Annexe C to Statutory Declaration 17656.

[45] ibid., Statutory Declaration 18929, William Hall, shipwright, 24 March 1887, p. 4.

[46] ibid., Statutory Declaration 18930, Thomas Mason, 24 March 1887.

[47] ibid., Statutory Declaration 17657, William Stone, 21 February 1877, p. 3.

[48] ibid., Statutory Declaration 17656, p. 2.

[49] PROV, VPRS 460/P0, Unit 2173, Application No. 32617.

[50] Paul Vincent Guggenheimer et al v Registrar of Titles, in the Supreme Court of Victoria, Melbourne, 22 April 2002, Victorian Government Reporting Service, p. 6.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples