Last updated:

‘“New History from below” captured within the records of the Bendigo Regional Archives Centre’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 11, 2012. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Michele Matthews.

Bendigo Regional Archives Centre (BRAC) is the caretaker of records created by six former councils, now all under the umbrella of the City of Greater Bendigo. Established in 2008, it is a rich resource for genealogists and local historians. The three sections in this article – Gender, Court Records, and Racism – each elaborate upon the central argument that local records held at BRAC allow researchers to tell ‘New History from below’ – that is, to research the stories of women, children and minority ethnic groups who have been omitted from local and wider history writing, partly because the records now housed at BRAC were previously difficult to access. That hurdle is no longer an issue.

The newly established Bendigo Regional Archives Centre (BRAC) had its genesis in the 1980s, when locals, including the editor of the Bendigo advertiser and myself, argued that Bendigo needed to have its own archives centre (and museum) to house the region’s rich history dating back to the Victorian gold rush. The culmination of many local grassroots meetings was the establishment of BRAC in 2008 as a Place of Deposit (POD) to care for permanent public records, as specified in the Victorian Public Records Act 1973. As well as having POD status, BRAC aims to collect and acquire private records from regional individuals and organisations.

BRAC’s establishment is definitely unique, being a joint partnership between the City of Greater Bendigo, PROV and the Goldfields Library Corporation. Each partner provides expertise and/or funding. Such a partnership has never occurred before in Victoria. We know that other regional centres are watching BRAC’s development with interest.

The reading room and the on-site repository, which houses half a kilometre of high-usage records, are located upstairs at the Bendigo Library, physically cheek-by-jowl with the Library’s Research Centre. This means that any researcher taps into the expertise of Margaret Sawyers (archivist), myself (historian), and the wonderful research librarians.

I contend that the use of local and regional archival records, for any academic or non‑academic research purposes, add a depth to the telling of Australian history that is still lacking in work undertaken in this country today. Grassroots perspectives of key events in our history – ranging from the development of white settlement outside Melbourne prior to 1900, to Federation, to the post World War I influenza epidemic and the Great Depression – all exist within the varied, inter-related series housed at BRAC. Hundreds of fresh stories await eager postgraduate students (and any other researchers) who want to move away from more mundane history writing that only focuses on prominent individuals and capital cities, and instead delve into what historian Martyn Lyons recently called the ‘New History from below’.[1]

BRAC records allow any historian, professional or amateur, to ‘hear’ the voices of working‑class women and men, of minority residents from other countries (Cornish, German and Chinese in the case of Bendigo and district), of people who have never made it to the pages of any local history publication, let alone a wider Australian study – truly ‘New History from below’ waiting to be told.

To this day, there has still been only one all‑encompassing history of Bendigo written, and it was first published in 1973.[2] Frank Cusack, its author, privately bemoaned the fact to me that, when he was researching that work, he had to rely on records held at the State Library of Victoria – pre PROV – and on microfilm of our long‑established newspaper, the Bendigo advertiser. He could not gain access to any local government records in the 1960s.

This anecdote leads me to the important issue of access to the many records now held at BRAC. Prior to 2008, these sources were housed and cared for by the records staff employed by six former individual councils – the City of Bendigo, the Borough of Eaglehawk, and the shires of Huntly, Marong, McIvor and Strathfieldsaye (the smaller boroughs of Raywood and Heathcote had earlier been absorbed into Marong and McIvor shires respectively).[3] The time constraints and the skills of those staff determined whether or not any historians were permitted to use the records. Charles Fahey’s 1978-81 PhD research on ‘social mobility’ within Bendigo and north central Victoria in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a unique example. He told me he used both Bendigo and Eaglehawk’s rate books during the course of his research.[4]

My own honours work in 1983, which saw me searching for surviving correspondence and minutes about Bendigo’s response to Federation, was a rare instance where permission was given to use the former Sandhurst/Bendigo Council’s extensive nineteenth‑century correspondence collection (the care of which is now a rewarding part of my duties at BRAC).[5] The only person I know of who used Bendigo Council’s twentieth‑century correspondence, also in the early 1980s, was Charlie Fox, for his ground‑breaking analysis of the Great Depression’s politicisation of workers in Bendigo, Ballarat and Geelong.[6]When Michael Roper conducted his Masters research in 1984, focusing on cultural traditions in Sandhurst between 1852 and 1886,[7] I supervised his access to the collection, because I was then employed by Bendigo Council to write a catalogue for their nineteenth‑century correspondence. Bendigo’s town clerk allowed me to do this work after I explained to him how such a catalogue would ensure easier access to the correspondence for researchers and staff alike, as well as help to preserve the documents by reducing their handling.[8]Since joining BRAC in 2008, I have been able to type up an accompanying index to this catalogue, with subjects and individuals cross‑referenced; this index makes the nineteenth‑century correspondence even more accessible to staff and researchers.

The following sections of this article – Gender, Court Records, and Racism – show how the stories of forgotten individuals can be brought to light using the records housed at BRAC. These accounts are of course only the tip of the iceberg; many more stories wait to be told.

Gender

Even short autobiographical accounts by local female correspondents in their own words and handwriting give us insights into the issues that concerned female ratepayers and residents of nineteenth‑century Bendigo. A minority wrote letters of complaint about issues they had with their local council.

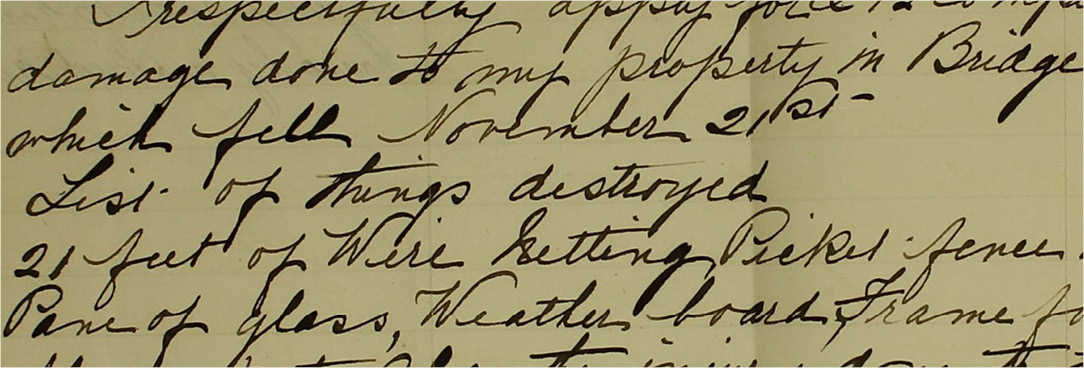

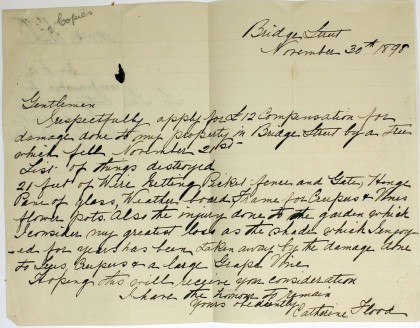

Catherine Flood made a detailed complaint about the state of her Bridge Street home and garden in November 1898, after a street tree fell into her property. She made it very clear to the councillors which damage bothered her the most: ‘the injury done to the garden which I consider my greatest loss as the shade which I enjoyed for years has been taken away by the damage done to Trees, Creepers & a large Grape Vine’.[9]

There were hardship letters from women like the widow, Eliza Haythornwaite. In 1886, she asked for a refund of the two lots of impound fees she had paid council because of her wandering cow and calf. She assured the councillors this would no longer be an issue because she had sold the carefree cow, but the refund was necessary because ‘I am a poor Widow with 8 children to support…’.[10] The Sandhurst rate books show that from 1882 to 1890 she was the owner and occupier of her home at the corner of Thistle and Rowan streets, with the land and house valued at £14.[11]

In contrast, BRAC records contain examples of local women who were more than comfortably off. One such example came to light when descendants of Amelia Burstall visited BRAC in 2010. They believed the family may have had money in the past, but had no details. The Sandhurst rate books showed that in the two decades 1868-1888 Amelia owned numerous blocks of land, culminating in ownership of nine blocks in 1884, all being geographically located within the one suburb of White Hills.[12] In 1873, she owned and lived on a farming property, valued at £40, located in the Parish of Lockwood within the Shire of Marong. Her occupation is delightfully recorded as ‘farmeress’.[13]

Our own ladies’ petition, dated 12 November 1873, is a rare example of large numbers of Sandhurst’s women expressing their deep concerns about an issue. In this case it was an attempt to use a section of the city’s central public recreational space, Rosalind Park, for sports activities which interfered with their use of this public retreat. This petition was signed by a total of 146 women who called themselves ‘Wives & Daughters of the Ratepayers’.[14] Their stated addresses were tightly concentrated in the very middle‑class residential blocks within walking distance north of the park (only a sprinkling of addresses were further afield).

The wording of this petition’s prayer is very powerful, particularly points 2 and 3 which assert their rights:

2. That such destruction of the ground would be depriving us of the only outdoor pleasurable place of resort within the City and is a deliberate interference with our domestic rights and priveleges.

3. That your petitioners earnestly hope your Council will see the absolute necessity for voting against the proposals … and your petitioners … will be for ever grateful.

Mothers and daughters like Jane Vahland and her three girls signed in familial order. They were the respected family of the city’s most famous architect, Wilhelm Carl Vahland. Surprisingly, the daughters were born in 1864, 1866 and June 1873, so the older girls were aged only nine and seven, and the youngest five months old, at the time this petition was created![15]

The sports activities these women objected to did not eventuate. The city’s main sports ground located in Rosalind Park, now our Queen Elizabeth Oval, was not commenced until the 1890s and is located in the southernmost corner of the park, not the lower section referred to in the petition.[16]

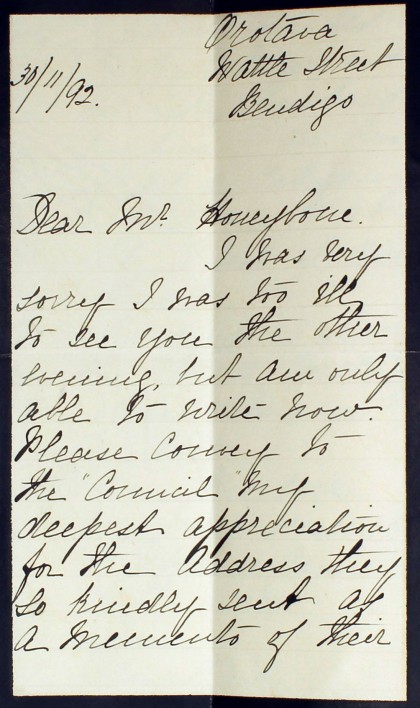

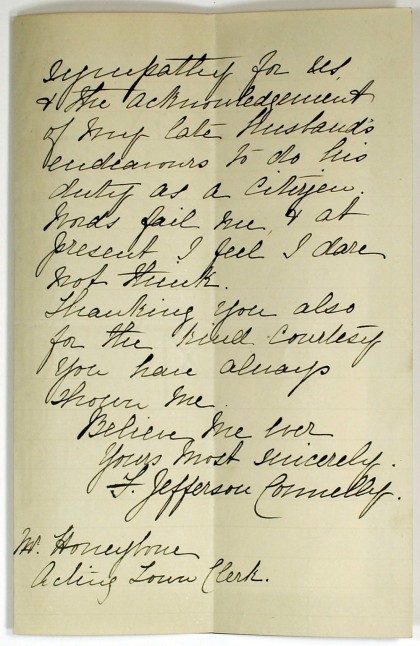

Examples of mourning or bereavement letters, complete with black edging, from female residents to the council have also survived. The young Frances Connelly, wife of Thomas Jefferson Connelly who was the city’s first native‑born and to this day its youngest mayor (aged only twenty-nine when he wore the mayoral robes), thanked Acting Town Clerk Honeybone for ‘the Address they so kindly sent as a memento of their sympathy for us and the acknowledgement of my late husband’s endeavours to do his duty as a citizen’.[17]

The ‘us’ refers to their three young children, aged only seven, six and four at the time of their father’s death. The enormity of her personal loss explains her concluding comment: ‘Words fail me, & at present I feel I dare not think.’ Connelly died of apoplexy, at the age of only thirty‑four, on 18 October 1892. This nearly unknown young champion of Australian Federation passed the national baton on to his friend and fellow stalwart believer, Dr John Quick.[18]

Bendigo even has its own local female suffrage petition, signed by women and men, and penned by the same Dr John Quick on 2 July 1894. Quick was, perhaps, Bendigo’s answer to John Stuart Mill. He was definitely the writer of the petition’s prayer and the first signatory; as his only biographer, I would recognise his unique scrawl anywhere.[19] The twenty‑one petitioners asked the Mayor to convene a public meeting ‘for the purpose of considering the advisability of extending the franchise to women’.[20] Relative to the fact that South Australia, the first colony to grant women suffrage rights, did not do so until 21 December 1894, five months after this local petition, means this small local document is historically intriguing.

Our recently launched Petitions of the people online project not only allows genealogists to find missing pieces of their family tree puzzles; there are also petitions that capture stories and individuals who do not appear in other primary or secondary sources. One such example is Jane Ruff. The Pioneer index told me that she married Raymond Ruff in 1870, and was the mother of seven children born between 1871 and 1886.[21] But Jane did not appear in her own right in the Sandhurst rate books. Her husband was the owner of the family home. However, they were struggling financially, as an extra note in the 1878 rate book showed ‘Insolvent. No Assets’.[22] Perhaps this financial situation prompted Jane to tender for the Sandhurst Council’s dust cart contract in 1880. She was successful, and held the contract for ten years. This was a most unusual occupation for a woman to undertake at that time in a provincial city.

It is only the fact that her tender was unsuccessful in 1890, leading sixty‑nine fellow citizens to petition the council to reverse its decision, that we have these details about Jane’s working life as recorded in the petition’s prayer.[23] There is also a surviving letter from Jane herself, dated 5 September 1890.[24] She makes similar arguments to those in the petition: she had served the city ‘faithfully’ for ten years; she had purchased an extra cart assuming that her tender would be renewed; and there was only £1 difference between her tender and that of the successful tender.[25]

This letter left one clue that proved fruitful. I cross‑referenced the date of Jane’s letter against the minutes of the council’s finance committee because she had addressed the letter specifically to them. At a meeting held one week after Jane’s letter is dated, a fiery meeting of this committee took place. Councillors were divided over the way this tender had been handled. Finally, a motion was moved and seconded, and ‘Jane Ruff’s tender was recommended for acceptance’.[26]

Occasionally a male correspondent wrote to the council about protecting the sensibilities of female residents. In March 1892, the Wade Street district’s local councillor, DB Lazarus (a mining magnate), was told that the sexual activities of McManara’s bull were inappropriate because ‘the cows from the district is [sic] served in gaze of all the Children and Women of the Neighbor[hoo]d’.[27]

A unique extra column appears in the Bendigo rate books from 1910 which lists the number of residents living in each household within the boundaries of the City of Bendigo; from 1926 this column is then split further into the total number of males and females within each household.[28] Together with the usual information recorded for each property, this extra column provides us with fantastic detailed census data about Bendigo families. This is the only series of rate books housed at BRAC which contains this extra column. The data has already proved useful to our genealogy researchers. I look forward to it being used further in numerous types of studies.

Court Records

The court records for the busy Bendigo Court, as well as those for the neighbouring townships of Eaglehawk, Elmore, Heathcote and Huntly (and the further afield Rochester, Kyabram and Echuca) are all physically located at BRAC and have been processed by us. The legal transfer of these ninety‑one series into BRAC’s care is occurring at the time of writing. These records span the years 1858-1980s, and encompass all the different types of courts which existed over this long period – mines, insolvency, licensing, petty/magistrates, Supreme and Commonwealth branches.

While processing these records, I undertook some research using the Bendigo Court of Petty Sessions Cause List Books – Criminal Cases. During the nineteenth century, as today, crimes against a person such as abuse of a wife by her husband, rape, murder, and suicide were the province of the criminal sittings. But sprinkled throughout these entries were the many unexpected cases which dealt with children. It was during hearings, of what were deemed criminal cases in the nineteenth century, that ‘neglected’ children were told by the magistrate that they were to live in the Sandhurst Industrial School, which existed from 1868 to 1885.[29] Later, they were sent to other industrial schools located in or near Melbourne. Often the children arrived at court in sibling clusters – and they were not always orphans.

One such case, found in my study of 1875 as a sample year, was the Murphy boys – Thomas, Edward, John and James. The four of them, aged three, five, six and eight years, appeared together in court on 4 November 1875. The magistrate ruled that they were all to be ‘Committed to the Industrial School until attaining the age of 15 years’.[30] Unlike all of the other children found in my sample year, their father, John Murphy, was still living in June 1875 when he had a warrant issued for his arrest for lack of ‘Maintenance of 4 children.’[31] Just in that one calendar year, thirty‑four children – twenty‑one girls and thirteen boys – appeared in front of the Sandhurst bench charged with being ‘neglected’. In every case, except one, these innocent members of society were sent to an industrial school.[32]

Racism

What we term racism, as seen through twenty‑first century eyes, is abundantly evident within numerous records housed at BRAC. It is the fact that racism does not permeate all our local government series that is perhaps surprising. The main offender was Sandhurst/Bendigo City Council. Their series of voters’ rolls, which span the years 1896 to 1914, lump all local Chinese ratepayers together at the end of each ward’s lists of ratepayers, rather than placing them in correct alphabetical order as was done for all the Anglo‑Saxon ratepayers. The Borough of Heathcote rate books often did not even bother to give the Chinese landowner’s name; he was just referred to as ‘Chinese’.

Surviving, detailed reports to Sandhurst Council from its own health officer show that he was expected to regularly inspect the ‘Chinese quarters’, located close to the city’s central business district throughout the nineteenth century.[33] In November 1881, for example, Dr Cruikshank reported in detail that ‘On the occasion of my visit no prostitutes were observed by me nor men suffering from the effects of opium. Everything seemed orderly.’[34] Ironically, today this area is the site of the popular tourist attraction, the Bendigo Golden Dragon Museum.

In August 1882, the Central Board of Health in Melbourne sent an A3‑size poster to Sandhurst Council, being a ‘Sanitary Notice in the Chinese language’ to be displayed about the city.[35] The stereotypical idea of the Chinese as immoral, dirty opium smokers is truly reinforced by this surviving correspondence.

What about the city’s most prominent Chinese resident, James Lamsey, acting as guarantor for two other Chinese men who wanted to sluice a section of Bendigo Creek in 1895?[36] White applicants never needed a guarantor when they applied to the council to undertake similar activities.

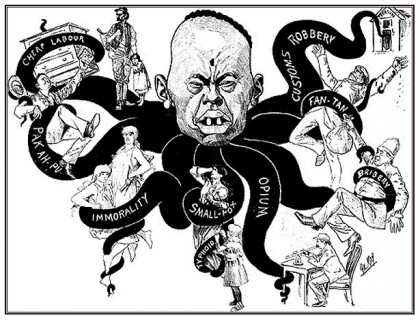

While these documents are obvious examples of administrative racism, it was intriguing to find, within the smaller Borough of Heathcote rate books, open listings for an ‘opium house’ within its boundaries in the 1870s.[37] How enterprising for that local council to happily collect revenue from establishments which are represented in the infamous contemporary Bulletin cartoon ‘The Mongolian Octopus’ as one of the key factors behind Anglo‑Saxons’ dislike for the Chinese population who inhabited the colonies during those years!

In contrast, our Petitions of the people site contains one pair of petitions which display the antithesis of racism – unity between Chinese and Anglo‑Saxon residents undertaking the same occupations. Stallholders and their suppliers, who worked at the Bendigo Council’s market, were in agreement that the lighting at the market was inferior, especially in the early hours of the morning when they were trying to set up their produce stalls. Two petitions were duly dispatched to the council in April 1899. One was signed by fifty-eight local ‘Chinese Market Gard[e]ners, Fruit Growers, Hawkers, Dealers and others’, with one of them as the witness to all the others’ signatures. The second petition was signed by eighty-seven Anglo‑Saxon ‘Fruit Growers, Market Gard[e]ners, Dealers, Hawkers and others’. The unexpected feature of this second petition was that these petitioners also witnessed each other’s signatures.[38]

Conclusion

The regional records housed at BRAC are rich in detail and full of historical insights. By their very nature, they contain the ‘New History from below’ – stories that are worthy of being told not just for their own sake, but as a means of adding grassroots depth to Australian history writing.

Processing continues at BRAC; the big task at the moment is to identify the more than 300 petitions within the Bendigo correspondence series, in order for them to be progressively digitised, transcribed and researched over coming months. The first petition prayer themes highlighted have been 1) the concerns of people with the same occupation 2) women, and 3) issues with the chimes of the post office clock. To date, we have processed 133 series – 42 local government series (rates, minutes, staff records), and 91 court series. This totals 1500 volumes – and we are not finished yet!

BRAC is becoming increasingly well known locally, in Victoria and interstate. Our statistics show that in the 2009-10 year, 186 researchers used 821 records, while in 2010-11, 258 researchers used 1241 records. Over these two financial years, Victorian researchers have doubled from 38 to 83, and interstate researchers have doubled from 15 to 29. In this latest financial year 2011-12, with two months to go, we have already exceeded both the researcher and records usage figures for the previous year.

Margaret Sawyers and I pride ourselves on the service we offer our clients, whether in person, via the telephone, or by email. Together with the research librarians, the top floor of the Bendigo Library is a true ‘one stop shop’ for anyone who visits us. Our researchers have varied skills and backgrounds. City of Greater Bendigo staff have prepared conservation reports and heritage studies. Genealogists seek any information they can find about their ancestors. La Trobe University Bendigo undergraduate and postgraduate students have researched aspects of the city’s history, architecture and planning using BRAC records. Professor Rod Home, the authority on the life of Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, was thrilled to be told about the surviving correspondence from Mueller to Sandhurst Council. These letters will now be included in his mammoth biography of Mueller.

Martyn Lyons observed rightly, I believe, that historians have too often been content to use only the writings of ‘educated people’ to tell the past, and to rely on ‘indirect sources’ for the stories of the ‘silent masses’.[39] This omission can now be redressed because researchers can access and make full use of the unique local records housed at BRAC.

Endnotes

[1] M Lyons, ‘A New History from below?: the writing culture of ordinary people in Europe’, History Australia, vol. 7, no. 3, December 2010, p. 59.1.

[2] F Cusack, Bendigo: a history, Heinemann Australia Pty Ltd, Melbourne, 1973.

[3] These six councils were merged to form the City of Greater Bendigo in 1994. The City of Sandhurst existed from 1856 to 1891. In April 1891 a poll of ratepayers voted in favour of changing the city’s name back to Bendigo.

[4] JC Fahey, ‘Wealth and social mobility in Bendigo and north central Victoria 1879-1901’, PhD thesis, Department of History, University of Melbourne, 1981.

[5] MS Maslunka, ‘Bendigo: one community’s response to Federation’, BA Hons thesis, Department of History, University of Melbourne, 1983 (this thesis was written under my maiden name).

[6] C Fox, Fighting back: the politics of the unemployed in Victoria in the Great Depression, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 2000 (this was the published version of his 1983 PhD work).

[7] M Roper, ‘The invention of tradition in Sandhurst 1852-86’, MA thesis, Department of History, Monash University, 1986.

[8] I have blessed the late Professor Greg Dening often for his wonderful archives workshop which I undertook as an honours subject at the University of Melbourne in 1983.

[9] Bendigo Regional Archives Centre (BRAC), VA 4862 Sandhurst Council and VA 2389 Bendigo Council, VPRS 16936/P1 Inwards Correspondence, Unit 47, Bundle 8-30 November 1898, Catherine Flood to Bendigo Council, 30 November 1898.

[10] ibid., Unit 23, Bundle 17-30 June 1886, Eliza Haythornwaite to Sandhurst Council, 18 June 1886.

[11] BRAC, VA 4862 Sandhurst Council and VA 2389 Bendigo Council, VPRS 16267/P1 Rate Books, Units 26-34 (1882-1890).

[12] ibid., Unit 28 (1884).

[13] BRAC, VA 2464 Marong (Shire 1864-1990), VPRS 16266/P1 Rate Records, Unit 10, Rate Book 1873, p. 8, Rate No. 197.

[14] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 12, Bundle 12 November 1873, Wives and Daughters of the Ratepayers to Sandhurst Council. This petition can be viewed online as part of BRAC’s Petitions of the people digitisation project.

[15] BM Jackman (comp.), Bendigo Advertiser personal notices, vol. 1, 1854-1880, self‑published, Bendigo, 1992, pp. 47, 55, 78.

[16] While I did not have the time to pursue this story myself, an interested researcher could trace it through the connections between this petition, Council’s minutes and the Bendigo advertiser.

[17] As she was writing in a formal capacity, Frances signed her name here as Mrs Thomas Jefferson Connelly. BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 35, Bundle 21-30 November 1892, Mrs T Jefferson Connelly to Bendigo Council, 30 November 1892.

[18] MS Matthews, ‘A forgotten father of Federation: Sir John Quick 1852-1911’, MA thesis, School of Arts and Education, La Trobe University, Bendigo campus, 2003, chapter 5, pp. 73-5.

[19] ibid.

[20] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 40, Bundle 1-14 July 1894, Dr Quick to Bendigo Council, 2 July 1894. This petition is available online.

[21] Pioneer index, Victoria 1836-1888: index to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, November 1998 (CD‑ROM).

[22] BRAC, VPRS 16267/P1, Unit 22, p. 175.

[23] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 31, Bundle 16-30 September 1890, Petitioners to Sandhurst Council, September 1890. This petition is also available online.

[24] I have compared the letter and the prayer; the handwriting is not the same, which means that the petition was written by someone else.

[25] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 31, Bundle 1-13 September 1890, Jane Ruff to Sandhurst Council’s Finance Committee, 5 September 1890.

[26] BRAC, VA 4862 Sandhurst Council, VPRS 16342/P1 Committee Minutes, Unit 18, 12 September 1890, p. 552.

[27] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 35, Bundle 1-15 March 1892, George Knight to DB Lazarus Esq, 1 March 1892. (This letter was attached to a petition objecting to McManara’s piggery; the bull issue seems to have been an afterthought.)

[28] BRAC, VPRS 16267/P1, Units 55, 70.

[29] F Cusack, Candles in the dark: a history of the Bendigo Home and Hospital for the Aged, Queensberry Hill Press, Carlton, 1984, Chronology.

[30] BRAC, VA 3008 Bendigo Courts (previously known as Sandhurst Courts), VPRS 16736/P1 Court of Petty Sessions Cause List Books – Criminal Cases, Unit 11, May 1875 – January 1876, 4 November 1875.

[31] BRAC, VA 3008 Bendigo Courts, VPRS 16735/P1 Court of Petty Sessions Cause List Books – Civil Cases, Unit 13, February 1875 – July 1875, 10 June 1875.

[32] BRAC, VPRS 16736/P1, Units 10 and 11, 1874-1876. These volumes match perfectly the entries contained in PROV, VPRS 4527 Children’s (Ward) Registers.

[33] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 17, Bundle 17-30 November 1881, Health Officer to Sandhurst Council, 18 November 1881.

[34] ibid., Dr Cruikshank, Health Officer, to Sandhurst Council, 25 November 1881.

[35] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 19, Bundle 17-31 August 1882, Central Board of Health to Sandhurst Council, 19 August 1882.

[36] ibid., Unit 42, Bundle 1-12 November 1895, James Lamsey to Bendigo Council, 12 November 1895.

[37] BRAC, VA 2686 Heathcote I (Borough 1863-1892), VPRS 16334/P1 Rate Books, Unit 3 1872-1881, p. 68, Rate No. 494 (1876).

[38] BRAC, VPRS 16936/P1, Unit 48, Bundle 4-28 April 1899, Petitioners to Bendigo Council, April 1899. These petitions are also available online.

[39] Lyons, p. 59.4.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples