Last updated:

‘Mud, Sludge and Town Water: Civic Action in Creswick’s Chinatown’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 11, 2012. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Elizabeth Denny.

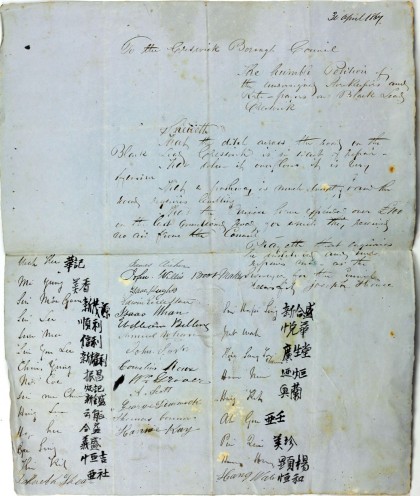

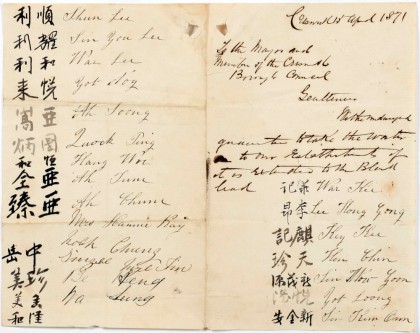

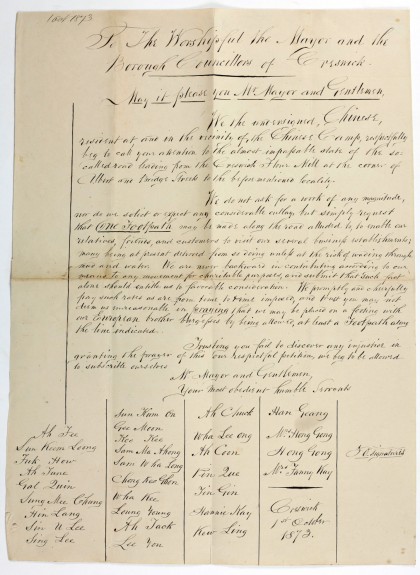

This article examines four petitions written by the Chinese community on the Black Lead in Creswick between 1867 and 1873. The petitioners wrote to their local council requesting a water supply to their settlement as well as infrastructure to improve access and drainage. The petitions contain signatures in Chinese, which may be useful for family history research and for the study of networks of Chinese in colonial Victoria. The documents show that Chinese residents were willing and able to participate in the processes of local government.

The four petitions are among the records of the Borough of Creswick, now held in the Ballarat Archives Centre. While court and mining records have already been well utilised to study the Chinese on the goldfields of central Victoria, this article shows that municipal records can also be a valuable resource. They provide a context for understanding why three of the four petitions failed and why the Chinese community in the area declined after the 1870s.

Finding the Chinese community in early Creswick municipal records

During the 1850s gold rush, the town of Creswick, located in west-central Victoria about sixteen kilometres north of Ballarat, had a population of over 25,000 including 4000 Chinese. Today, the whole population of Creswick is around 3000, and the only tangible traces of the nineteenth-century Chinese population are memorials in the cemetery and a plaque on a footbridge in Calembeen Park.

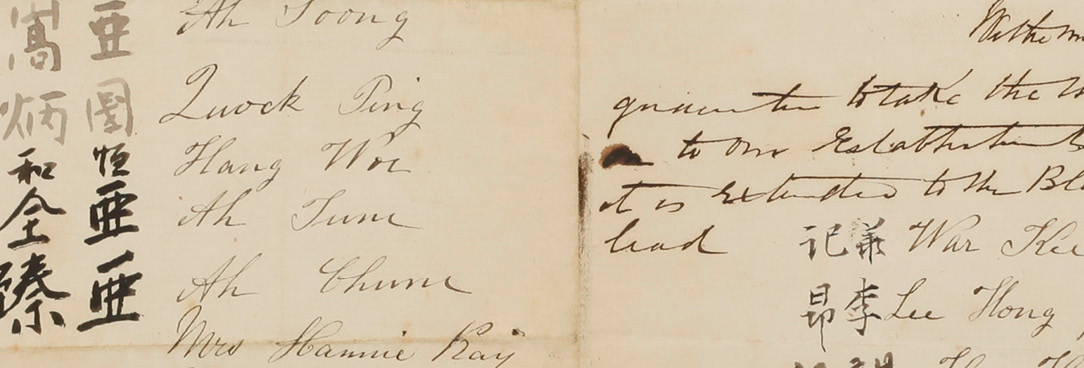

In the files at the Ballarat Archives Centre is a petition from Chinese residents on the Black Lead, dated April 1871, asking the Creswick Borough Council to supply town water to their premises. The petition interested me for several reasons. The petitioners’ names are given both in an English form and in Chinese characters, and among the names I recognised those of several Chinese settlers who had made their mark in nineteenth‑century Australia.[1]

Kathryn Cronin’s classic study Colonial casualties[2] describes the difficulties faced by Chinese immigrants who were attempting to establish themselves in colonial Victoria, so I was curious to find out whether the petitioners succeeded in getting the water laid on. I found the answer when I looked into the municipal records of the time.

Petitions from Chinese residents are rare survivals in the colonial records, but three other petitions from the Black Lead community exist in the files. These petitions, when read together with the minutes, contract books and rate books of the Borough of Creswick,[3] show that a group of prosperous Chinese from the camp at Black Lead were using the local political system with confidence and skill. What was once the Black Lead Chinatown is now under the lake and lawns of Calembeen Park, but the petitions survive and preserve the voice of that vanished community.

After the 1870s there are no more petitions from the Chinese community at Creswick. I wondered whether there was a reason for this, apart from a possible loss of the records. Perhaps there were changes within the Black Lead community and it had become less confident or less politically active.

Petitions and Civic Action

Petitions were a standard device of politics in colonial Victoria and hundreds were sent to the colonial government and can be found in the archives at PROV. The Chinese, with a long history of urban, literate and bureaucratic government, were familiar with the use of petitions within their own political culture, and used them to represent their views and wishes to the authorities. Anna Kyi’s two articles in Provenance in 2009 investigated such petitions in the 1850s and 1860s. Her discussion includes consideration of the value of petitions for understanding the political activity of the Chinese in colonial Victoria, and the importance of bilingual records for both family research and the study of various communities of Chinese residents.[4]

Petitions from residents were the standard way to get municipal services and infrastructure, but comparatively few of the many surviving petitions from municipal ratepayers and residents are from Chinese communities. One such petition, held at the Bendigo Regional Archives Centre, was composed by the Chinese market gardeners of Bendigo in 1899. The purpose of the petition was to ask the city’s mayor and councillors to provide better lighting at the fruit and vegetable market.[5]

The four Black Lead petitions similarly show local Chinese residents dealing in municipal politics. The petitions help us to understand the experience of Chinese residents on the Victorian goldfields as towns and a civic culture were established in the area. They give a glimpse of politics at the municipal level, and of a large ‘outsider’ group working to be recognised and accommodated within the mainstream political system.

The Petitions from the Black Lead

The ratepayers of the Black Lead requested civic infrastructure and repairs. They wanted paths and roads built or remade, the overflow of the sludge channel dealt with, and the town water extended to their properties.

Three of the four petitions sent to Creswick Borough Council between 1867 and 1873 by residents of the Black Lead contain the names of Chinese residents in Chinese characters. The characters show a range of literacy, from the competent to a barely literate scrawl. In this they are similar to the range of literacy found on petitions from European residents. Most of the Chinese characters on each petition are written by one or two persons, and so the names tend not to be personal signatures, which is typical of petitions from Chinese groups in this period.

While the petitions from the Black Lead contain both Chinese and European signatories, Chinese signatories are not found on petitions from other neighbourhoods in Creswick. There are no women’s names on the first petition, unlike the later three. For transcriptions of these petitions and some general background, see the PROV Wiki Chinese language records at PROV.

The Black Lead Camp

What was the Black Lead like when it was identified as the centre of the Creswick Chinese community by both the Chinese residents and the local council of the Borough of Creswick in 1871? In a detailed report on Creswick in 1864, the Argus only briefly mentions the Chinese camp: ‘They have one of their large, miserable, ricketty encampments just outside the town, and round about they have numerous market-gardens …’[6]

The petitions and associated records of the Borough of Creswick, including minutes, municipal rate books and contract books, can be used to sketch in more details of the large Chinese camp on the Black Lead. In the 1864 rate records the buildings on the Black Lead are rated at a low value, and frequently described as ‘tenement’. No brick or stone buildings are recorded. This does not change over the next decade. The Black Lead camp seems to have consisted of simple wooden buildings. Shops, workshops and dwellings and a large number of saloons are the most common buildings listed. Lodging houses, opium dealers, smiths, cooks, a goldsmith, a barber, a tailor, doctors, chemists, herbalists, a fruiterer and a fish dealer were also to be found in the camp.[7]

Lack of Infrastructure on the Black Lead

The petitions tell us that the residents of the Black Lead found it difficult to get around in wet weather. On 30 April 1867 ‘the undersigned Storekeepers and Rate‑payers on Black Lead Creswick’ pointed out:

That the ditch across the road on the Black Lead Creswick is in want of repair – That when it overflows it is very offensive [-] That a pathway is much wanting and the road requires levelling[.]

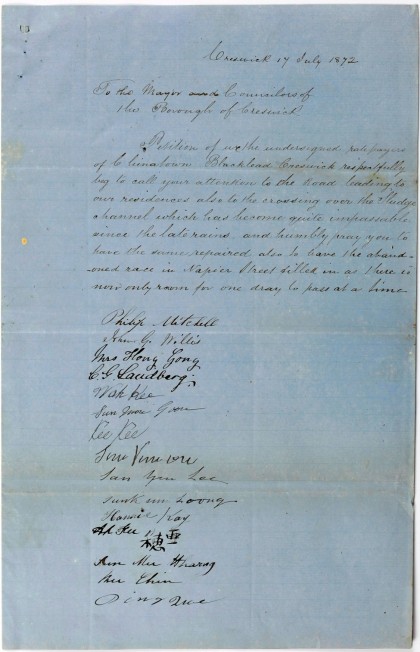

On 17 July 1872, five years later, another petition stated that

… we the undersigned ratepayers of Chinatown Blacklead Creswick respectfully beg to call your attention to the Road leading to our residences also to the crossing over the Sludge channel which has become quite impassable since the late rains, and humbly pray you to have the same repaired also to have the abandoned race in Napier Street filled in as there is now only room for one dray to pass at a time.

The council agreed to build a footbridge for the Black Lead community.[8] However, a year later the residents were still waiting and requested in a further petition on 1 October 1873 that

One Footpath may be made along the road alluded to, to enable our relatives, friends, and customers to visit our several business establishments; many being at present deterred from so doing unless at the risk of wading through mud and water.

The petitioners pointed out that they were full citizens of the Borough of Creswick:

We promptly and cheerfully pay such rates as are from time to time imposed, and trust you may not deem us unreasonable in praying that we may be placed on a footing with our European brother burgesses …

Not everyone who lived in Creswick was a burgess and entitled to vote in the municipal elections. The council minutes of 1872 and 1873 recorded the decisions of the yearly Borough Revision Court as it updated the Burgess Roll.[9] The Burgess Roll recorded those ratepayers, or burgesses, who were eligible to vote in municipal elections because they owned property of sufficient value in the Borough of Creswick to qualify, had paid their rates, and wished to be included on the roll. The roll listed the name of each burgess, profession, property details and the number of votes each was entitled to, depending upon the amount paid in rates.

Living in a Mining District

The Black Lead camp during the winter of 1872 had developed a serious problem with contaminated water and poor drainage directly related to the mining industry that dominated the town. The Borough Inspector was instructed to visit the camp with the Health Officer,

at the rear of which, owing to the imperfect state of the drainage they found a large quantity of water in a putrid state which they believed must be injurious to the health of parties residing in that neighbourhood.[10]

Two weeks later the council was told that the inspector had found more problems at Black Lead, notably

the ground subsiding, caused by the mining at the rear of the Chinese stores and dwellings. In one place the ground sunk 4 feet carrying with it a brick chimney and the corner of a wood building, probably had the house been built of stone the disaster would have been most serious to the inmates.

In several places large holes were to be seen where the ground had given way at the surface which led him to conclude that the place had been completely undermined; in consequence of which the drainage had become very imperfect, and the whole of the waste water and filth from the store dwellings and pig sties was forming one large unsightly stagnant pool which was very offensive, and would be extremely so if allowed to remain until the summer season it would render the place unfit for human habitation.[11]

Black Lead was not the only place in Creswick with drainage problems and the inspector

next called attention to the low land at the back of Montgomery and Riordan’s Hotels where the drainage was very bad and suggested that the Board might visit this place when proceeding to inspect the Black Lead.[12]

If the Black Lead was as muddy in winter as the petitions claim, then it was probably dusty in summer. It would have been crowded and busy, with pigsties[13] and stables adding to the noise and smells.

The Chinese Community in Creswick

Creswick had a large Chinese community, and the contemporary rate books show that in the decade before the petitions from the Black Lead, the Chinese population was not confined to Chinatown, but was also scattered throughout the town of Creswick and the surrounding mining leads.

The rate books in the early decades of the borough provide minimal details about the properties listed. They do not describe the number of rooms in each building. They record only the ratepayer of each property, and do not indicate if any other people – family members, tenants, employees – lived on the premises. The rate books cannot therefore be used to give reliable figures for the actual Chinese population in any part of Creswick. They can however show patterns of habitation in the Borough of Creswick, and locate individuals who were ratepayers.

Chinese businessmen had properties in the main street, Albert Street, which had a number of substantial shops, hotels and other public buildings:

The town consists of a main street – Albert-street – of great width, of an anabranch entitled Victoria-street, and of two or three little-used cross thoroughfares. We stroll through it, and return with a general impression of people who have not too much to do, of Chinamen and Chinese stores, of heavy boots, jumpers, and moleskin trousers…[14]

Three Chinese residents, with names written in Chinese and English, are listed as ratepayers in Albert Street in rate records from 1860.[15]

Chinese Residents Move to the Black Lead

The rate records indicate that throughout the period the petitions were compiled, Chinese residents of Creswick were moving to the Black Lead settlement from other locations in the town. Peng Que, a local mining entrepreneur and business man,[16] and two of the families with names on the petitions – Lee Hang Gong and Sarah Hang Gong,[17] and Hannie and Frances Kay – moved into the camp during this time.

Peng Que

Peng Que, who signed three of the petitions, had been renting expensive premises in Albert Street in the years from 1867 to 1870. In 1870 his name is crossed off the water rate list for Albert Street, and he is not listed in the Creswick Borough rate books of that year. In 1872 he is listed as owner of a tenement on the Black Lead.[18]

Hannie and Fanny Kay

Hannie Kay, interpreter, his wife Frances (Fanny) and their family lived in South Hill and South Parade for several years. The family moved in 1867, and the rate books from 1867 to 1874 list both Hannie Kay and Fanny Kay as storekeepers and property owners on the Black Lead.[19] The Kays, one or both, were involved in all four petitions.

Sarah Hang Gong and Lee Hang Gong

Sarah and Lee Hang Gong lived in Napier Street Creswick, although they had businesses on the Black Lead. By 1871, however, it seems the family had moved into Chinatown and their fourth child, Selina, was born there.[20]

Black Lead Chinatown

In 1870, 1871 and 1872, up to fifty-seven rateable properties were listed on the Black Lead and nearly all were owned by Chinese residents or European women married to Chinese residents. The Black Lead was clearly identified as a Chinese community by both the Chinese in their petitions and in the local council minutes, and the rate books confirm it as the biggest grouping of Chinese residents in the town.

Town Water

In 1864 the Borough of Creswick, just one year old, planned to establish a town water supply, and expected that this would be a profitable enterprise. The Argus reported that

Creswick is not yet supplied with gas or water, but the latter it is speedily to have. The Government some time back handed over to the municipal council one of the gold-fields reservoirs, constructed in Bullarook Forest, eight miles away, together with a grant of £3,000 towards the conveyance of the water. Iron pipes have now been laid down to a distributing reservoir, at the White‑hills, a mile from the town, and 100ft. above its level; next year it is proposed to spend some £1,200 or £1,500 in bringing the water right into the township. At present, the only use it is put to is by the Chinese, who rent two sluice‑heads from the council, for which they pay £10 per week. Indeed the council appear likely to make a very profitable thing out of their waterworks, and believing so, they have declined letting them to the Chinese, who have offered to take them off their hands. The capacity of the distributing reservoir is 1,000,000 of gallons, and it is calculated that this filled once a week will supply the town, leaving a great volume to be let for mining purposes. If ‘John’ can make a good thing in this way, the council think they can too.[21]

By 1880 the Victorian municipal directory was reporting that the Borough of Creswick had

a good water supply brought from two reservoirs, one eight miles distant and the other five miles, through pipes and open aqueduct. Length of mains and aqueduct conveying water to the town eleven miles thirty chains; length of streets reticulated nine miles, thirty three chains.[22]

In their petition of 15 April 1871, twenty‑two Chinese residents of the Black Lead assured the Creswick Borough Council that they would ‘take the water to our Establishments if it is extended to the Black lead’. The petition is brief and businesslike, as are similar petitions for town water from other neighbourhoods in Creswick.[23] It was important that petitioners guaranteed that they would take up the water once it was supplied. The council had to cover the cost of administration and public works with rates and licence fees and with special grants from the Victorian Government. The water rates made up a significant part of the council’s total income from rates.

The council received £421 in water rates and standpipe use payments in 1870, and spent £500 on extending the town water supply.[24] In 1871, the European residents of Hard Hills in Creswick petitioned the Borough Council to extend the municipal supply water out to their homes. No Chinese names appear on this petition, even though the rate books show that clusters of Chinese were living in Hard Hills. These petitioners did not state that they would actually take up the water, and in fact, only one of them was willing to pay when the council piped water into the area. Councillor Jebb, on the Water Extension Committee, brought this up at the council meeting of 10 May 1871, and the Town Clerk was told to hunt up all the Hard Hills petitioners and get them to take up the water and pay for it.[25]

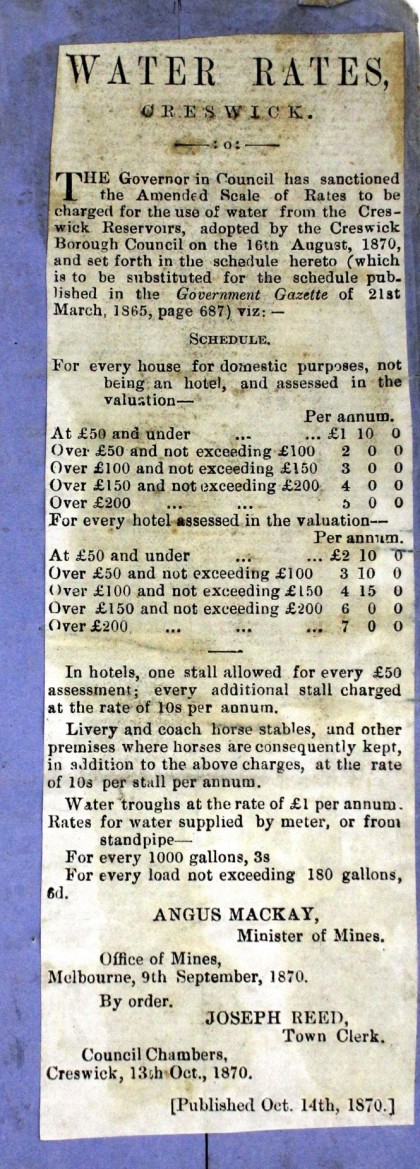

Not everyone was able to afford the water rates and have water connected to their premises. The water rates were high, as the printed schedule shows (see image below)[26] and reticulated water was still a luxury in Creswick in the 1870s. People were using standpipes in the streets even when the water supply system had been extended to individual properties in their neighbourhood.

Extending the Water to the Black Lead

By 1871 the council had organised the source of the town water, set up infrastructure to bring it to the township, and established a Water Extension Committee to handle requests for water supply. The process of supplying residents who wanted the water extended to their premises seems to have been fast and efficient.

The community on the Black Lead asked for water in April, and the work was completed in May, a week before the date set in the contract.[27] On 10 May 1871 the Town Surveyor reported to council that the tender process for the extension of waterworks to Black Lead was underway.[28] Then, on 24 May he reported that the contract had been carried out and that water had been laid on to twenty-two premises in the Chinese camp.[29] According to the water rate receipts of 1871, all the signatories of the 1871 petition took up the water newly supplied to Black Lead and paid for the water that they had requested. These petitioners possessed property on the Black Lead rated between £16 and £26, and they often owned more than one property.

Twenty‑one people in the camp signed the petition, however it is worth noting that more than thirty other ratepayers on the Black Lead, listed in the 1871 rate book, did not sign the petition or pay water rates.[30] The twenty-second name on the petition was Quock Ping, who is discussed below.

The Black Lead Petitioners

The petitions reveal a group of residents at the Black Lead camp who were politically competent and active. Three of them were men who were well known in Creswick for their professional work or entrepreneurial success. Lee Hang Gong and Peng Que, prosperous local businessmen, and Hannie Kay, the interpreter, obtained Victorian naturalisation and were on the Burgess Roll. They were reported on, often respectfully, in contemporary newspapers. Hannie Kay has been remembered in a plaque in Calembeen Park – the only individual of the thousands of Chinese residents of Creswick so honoured.

Hannie Kay and Lee Hong Gong both established resilient families in Australia through their marriages to local women.

Henry Quock Ping appears only once on a petition. He signed the 1871 petition for town water. A Chinese‑trained doctor, his name is not in the Creswick rate books or in the payment for water rates in 1871. He may have been operating a practice out of premises on the Black Lead when he signed the petition, but I first found him as a ratepayer in 1873 in Ballarat East.[31] He married Anna Jane Glenister in Ballarat in 1874 and the couple’s two sons, Henry James Quock Ping and Albert William Quock Ping, were born in 1875 and 1877 in Ballarat East.[32]

In June 1875, Henry made a formal application to the Victorian Medical Board to be registered as ‘a duly-qualified medical practitioner under the Medical Practitioners’ Statute 1865’.[33] Although he claimed to be equally qualified by his Chinese training as the European medical practitioners in the colony, the Board refused to accept his Chinese qualifications. His appeal to the Victorian Supreme Court later that year, against the Medical Board’s decision, also failed.[34] The following year, Quock Ping is listed as a doctor and owner‑occupier in Victoria Street, Ballarat East. When he died in 1877, he left his young family a large house in Ballarat East.[35]

The Women Who Signed the Petitions

Fanny (Frances) Kay and Sarah Hang Gong seem to have been particularly competent and adventurous women. They put their names to three of the petitions from the Black Lead, those of 1871, 1872 and 1873. There are many petitions addressed to the Borough council from other Creswick localities in the decade contemporary with the four Black Lead petitions, but these public petitions are signed only by men. Fanny Kay and Sarah Hang Gong were listed separately from their husbands as individual property owners and rate payers. Sarah was enrolled as a burgess in Creswick.[36] Judging from the Creswick records, Sarah Hang Gong and Fanny Kay were unusual women in their community.

Sarah and Fanny maintained successful marriages to men outside their own culture, at a time when such marriages received strong public criticism. In an age of high child mortality they raised their children to adulthood and established strong families continuing over more than one generation. Kate Bagnall describes a wide range of experiences and lifestyles in her study of marriages between Chinese men and non‑Chinese women in colonial Australia.[37] It is possible that Sarah and Frances found that differences between the Chinese and European cultural definitions of women and their roles as wives left them unusual opportunities to act and define themselves within their marriages and within their community.

Conclusion: Changes in the Black Lead Community after 1873

Kathryn Cronin describes the 1870s and 1880s as a period of discouragement, both economic and social, for the Chinese in Victoria, and notes that there was a large migration out of the colony over these decades.[38] In Creswick the petition for water in 1871 was promptly followed up by the council, but the other three petitions, requesting better access and drainage for the Chinese settlement, show a continuing problem with lack of infrastructure and growing impatience with the council’s response.

As far back as 1867, the Chinese petitioners had pointed out that they had already paid £100 for road works that were a borough responsibility. Five years later, in 1872, after a very unfavourable report on health and safety from the Borough Inspector, the council decided that the Black Lead community should be moved into a new settlement on higher ground. The council continued correspondence with the Central Board of Health and with the Department of Lands and Survey to have a new camp surveyed and the community moved, despite objections from the Black Lead residents.[39]

In 1873 the Chinese burgesses of Black Lead had pointed out to the council that they paid their rates promptly and contributed to local charities. They argued that the council should place Chinese ratepayers ‘on a footing with our European brother burgesses by being allowed, at least a Footpath’. The Creswick Council was clearly not going out of its way to support its Chinese residents to live in Creswick on their own terms.

Because political participation in Creswick Borough proved to be such a disappointing experience for the Chinese, many may have decided to find their fortunes elsewhere. In December 1873, in nearby Clunes, a miners’ strike developed into a riot when Chinese miners, quite possibly organised by Creswick Chinese entrepreneurs, were brought to Clunes to replace the striking miners.[40] Contemporary newspaper reports of the riot discuss increasing economic problems in the goldmining industry, and point out that where Chinese and European interests were in conflict, despite the legal and political rights of Chinese residents, a European majority prevailed.[41]

The economic opportunities in the town and surrounding district shrank as the easy gold was mined out. Creswick was offering fewer opportunities for its Chinese residents to engage successfully in the developing political and economic systems of colonial Victoria after the gold rush years. In addition, Victorians were hardening their attitudes to both Chinese residents and Chinese culture. As noted above, Henry Quock Ping ’s application to be registered as a doctor in Victoria was rejected. In 1875 Peng Que moved his business to the far north of Australia, and by 1880 the Hang Gong and Kay families had also left Creswick looking for opportunities in other Australasian colonies.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VA 657 Creswick I (Municipal District, 1858-1863; Borough 1863-1934), VPRS 5921/P0 Miscellaneous Council Files and Records, Unit 2, Petitions to Council no. 2.

[2] K Cronin, Colonial casualties: Chinese in early Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1982.

[3] PROV, VA 657 Creswick I, VPRS 3730/P0 Council Minute Books 1858-1934; VPRS 3704/P0 Contract Books 1859-1933; VPRS 3726/P0 General Rate Books 1864-1934.

[4] A Kyi, ‘Finding the Chinese perspective: locating Chinese petitions against anti‑Chinese legislation during the mid to late 1850s’, and ‘The most determined, sustained diggers’ resistance campaign: Chinese protests against the Victorian Government’s anti‑Chinese legislation, 1855-1862’, Provenance, no. 8, 2009, pp. 58-63, 16-28. M Chin, I Chin and C Scott, Chinese in the Creswick cemetery: headstones and transcriptions, a cultural interpretation, Chinese Heritage Interest Network, Blackburn South, Victoria, 2009, also provides a very helpful discussion of these issues in the context of the remaining Chinese inscriptions in the Creswick cemetery.

[5] Petition by ‘Chinese Market Gard[e]ners, Fruit Growers, Hawkers, Dealers and others’, dated April 1899, available in facsimile and transcription on the Bendigo Regional Archives Centre website (accessed 20 June 2012).

[6] ‘Country sketches. No. XII – Creswick’, The Argus, 30 September 1864, p. 6.

[7] PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Unit 1 Special Rate Book 1864-1870, Unit 2 General Rate Book 1864-1870, and Unit 3 General Rate Book 1870-1878.

[8] PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 9 Council Minute Books 1870-1872, p. 416.

[9] ibid., Reports of Creswick Borough Revision Court, Monday 15 July 1872, pp. 399-400; VPRS 3730/P0 Unit 10 Council Minute Books 1872-1874, Reports of Creswick Borough Revision Court, Wednesday 16 July 1873, pp. 196, 197 and 198.

[10] PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 9, pp. 424-6.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] The Central Board of Health recommended that no more pigs be kept in the Chinese camp: PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 10, p. 87; and on Wednesday 6 August 1873, Key Key asked the council’s permission to extend his water pipe to his pigsty at Black Lead to keep the sty clean: ibid., p. 211.

[14] ‘Country sketches. No. XII – Creswick’.

[15] PROV, VPRS 5921/P0, Unit 2, Rates General 1861-1931, see booklet titled Creswick assessment notices 1860 containing assessments in Albert Street that includes Chinese characters.

[16] For a biography of Ping Que see T Jones, ‘Ping Que: mining magnate of the Northern Territory, 1854-1886’, Journal of Chinese Australia, issue 1, May 2005, available online (accessed 20 June 2012).

[17] For a family history of Lee Hang Gong and Sarah Bowman, see V Lee with J Godwin and A O’Neil, ‘Lee Hang Gong/Sarah Bowman family history research: a progress report’, Journal of Chinese Australia, issue 1, May 2005, available online (accessed 20 June 2012).

[18]PROV, VPRS 5921/P0, Unit 2, Rates General 1861-1931. Peng Que’s name is crossed off the index of a booklet of water rate receipts for 1871, and replaced by the name of Pickles. The receipts include the names of all the Black Lead water petitioners. Their names are not in the index, however this may have been compiled before they were signed up to take the water. PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Unit 3, Rate no. 629 shows that in 1870 Peng Que was not in Albert Street and Hang War had taken on the lease, and in 1871 no Chinese names are listed in Albert Street.

[19] For a biography of Hannie Kay see S Couchman, ‘Kay, Henry (c.1828-1907)’, in the online database Chinese-Australian historical images in Australia (accessed 20 June 2012). For movements of the Kays around Creswick, see PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Units 1-3: 1868 Hannie Kay, interpreter, owner occupier Black Lead (rate number 381); 1869 Hannie Kay, storekeeper, owner occupier Black Lead (rate number 430); 1870 Frannie Key [sic], owner, Hong Gong is occupying tenant Black Lead (rate number 413); and 1870 Hannie Kay, miner, owner occupier Black Lead (rate number 420).

[20] Lee et al., ‘Lee Hang Gong/Sarah Bowman family history report’. For property owned by the Hang Gong family on the Black Lead in 1871 see PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Unit 3.

[21] ‘Country sketches. No. XII – Creswick’.

[22] Victorian municipal directory and gazetteer for 1880, Arnall & Jackson, Melbourne, 1880, p. 31.

[23] PROV, VPRS 5921/P0, Unit 2 contains petitions from Camp Hill, dated 10 February 1872, and from Hard Hills (undated, [1871]), requesting water in similar terms to the petition from Black Lead.

[24] PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Unit 3, see figures for estimated revenue and expenditure 1870.

[25] PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 9, p. 144, Council meeting 10 May 1871.

[26] PROV, VPRS 5921/P0, Unit 2, Rates General 1861-1931 contains a booklet of water rate receipts for 1871 with a printed schedule of water rate fees attached to the inside front cover.

[27] PROV, VPRS 3704/P0, Unit 1, pp. 111-12.

[28] PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 9, p. 132.

[29] ibid., p. 149.

[30] PROV, VPRS 5921/P0, Unit 2, Rates General 1861-1931, see booklet of water rate receipts for 1871; PROV, VPRS 3726/P0, Unit 3, see rate records for Black Lead in the years 1870 and 1871.

[31] See the rate books of Ballarat East for the years 1873 to 1877: PROV, VPRS 7258/P0.

[32] Anna Jane Glenister married Henry Quock Ping in 1874 (Pioneer index, Victoria 1836-1888: index to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, 3rd rev. edn, 1999 (CD-ROM), marriage registration no. 3701R). Henry James Quock Ping was born in Ballarat in 1875 (Pioneer index, birth registration no. 20874).

[33] ‘A Chinese doctor’, The Argus, 5 June 1875, p. 8.

[34] The Argus, 12 July 1875, p. 1c-d.

[35] Henry Quock Ping’s will and probate papers at PROV have been digitised and are available online.

[36] In 1872 new additions to the Burgess Roll included Hannie Kay, Sarah Hang Gong and Peng Que: PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 9, pp. 399-400.

[37] K Bagnall, ‘Golden shadows on a white land: An exploration of the lives of white women who partnered Chinese men and their children in southern Australia, 1855-1915’, PhD thesis, University of Sydney, available from Sydney digital theses (accessed 20 June 2012).

[38] Cronin, Colonial casualties, see the chapter ‘Chinese after the “Golden Age”’, pp. 124-32.

[39] PROV, VPRS 3730/P0, Unit 10, p. 17: in a meeting of 23 October 1872, the council recommended the removal of the Chinese camp; ibid., p. 49: on 6 December 1872, the Chinese petitioned the Commissioner Lands & Survey to be allowed tremain where they were, and a copy of that petition was reported to be enclosed in a letter from the Central Board of Health to the Creswick council; ibid., p. 87: on 8 January 1873 the council was still discussing the relocation of the Chinese camp.

[40] In her article on the Creswick Chinese camp, Carol Scott discusses the possibility that the recently developed contract Chinese labour force engaged by Chinese consortiums to work in the Creswick mines might have been that employed to work for the Lothair mine in Clunes (M Chin et al., Chinese in the Creswick cemetery, p. 85).

[41] Articles in the Argus, 11 December 1873, p. 4, and 15 December 1873, pp. 6-7 give a contemporary viewpoint of the Clunes riot.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples