Last updated:

‘Making Their Case: Archival Traces of Mothers and Children in Negotiation with Child Welfare Officials’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 11, 2012. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Shurlee Swain.

This paper looks at the ways in which child welfare records held by PROV can cast light on the interaction between poor women and welfare authorities as seen through the operations of the variously named predecessors of the current Department of Human Services. It contests the notion that mothers were uncaring and children were unwanted, showing how mothers and the predominantly female inspectors with whom they interacted were able to moderate many of the harsher, punitive aspects of welfare policy.

Christina Twomey’s book Deserted and destitute: motherhood, wife desertion and colonial welfare makes a convincing case for the influence of mothers on the shaping of Victoria’s child welfare systems.[1] Through some political activism and to a far greater extent by presenting their cases in the courts, mothers were able to show that Victoria needed a system to support children whose male providers had failed them. The Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864 marked the beginnings of that system, establishing the Industrial and Reformatory Schools Department, one of the first state children’s departments in the world. In older western countries children were dealt with as a sub-section of much larger poor relief systems. But the Australian colonies were determined not to introduce a poor law, so different provisions had to prevail.

The records of the Industrial and Reformatory Schools Department (which was not a department but a section of the Chief Secretary’s Office), later called the Neglected Children’s Department, the Children’s Welfare Department, the Social Welfare Department, and eventually the Department of Human Services, are, as the recent Ombudsman’s report makes clear, scattered and disorganised.[2] What I will focus on in this article are two identifiable sets of records, one well known and relatively easy to navigate, the other more obscure, and consider what light they throw on the lives of poor women forced to turn to the state for assistance in supporting their children.

The operation of the system was premised on a set of assumptions many of which seem alien to us today:

- Parents were anxious to be rid of their children and needed to be deterred from doing so

- Parents were a malign influence on their children and hence should be kept as far away from them as possible

- Parents who expressed an interest in their children should be treated with suspicion

- Children needed to be trained so that they would be able to earn their living and hence not become dependent on charity as their parents had.

In the early years when children were congregated in large, and often makeshift institutions, parents were only allowed to visit once a month and had to see and converse with their children in the presence of an officer of the institution. However, resourceful parents found ways to improve their access. In the case of single mothers it is clear that some were able to join the staff of such institutions as wet nurses, retaining contact with their own infants in this way. There were widows, deserted wives, and women with incapacitated husbands who were also able to find employment as attendants, a fact which was cited as a reason for closure by those who were opposed to the schools. The decision, implemented during the late 1870s, to close almost all the institutions and board children out with families across the colony, was designed, at least partially, to break any such contact. Parents were then not able to visit their children, indeed they were denied knowledge as to where their children were placed. Although letters could be forwarded via the central office, and, with supervision, vested in voluntary ladies’ committees, the department came to play a minimal role in children’s lives. Recordkeeping was not a high priority.[3]

Ward Registers

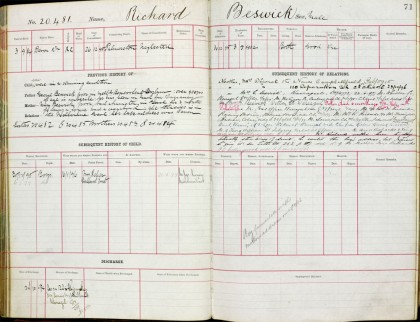

The leather-bound volumes of ward registers (some of which pre-date the usage of the term ward) were the focus of departmental recordkeeping and are the main source of records we currently have about children in care for the period prior to the 1920s.[4] In the registers each child is accorded a double-page spread. One side provides the basic identifying details of the child, the means by which it came into care, and the list of subsequent placements. The other page was used to detail any contacts with the department during the child’s time in ‘care’. The mother exists as a subject in these volumes but rarely as an actor. The identifying details for the child include name, address, occupation and marital status of the mother at the time of the child’s admission. The explanation of why the child came into care may provide more detail, sometimes positive, more often negative about the mother’s situation. While there was considerable effort expended in tracing paternity (so that maintenance could be collected) the only time a mother’s movements would be traced was if subsequent children were admitted to care (in which case there is an attempt to cross-reference, as indeed there is cross-generationally) or if she applied to have her children returned to her.

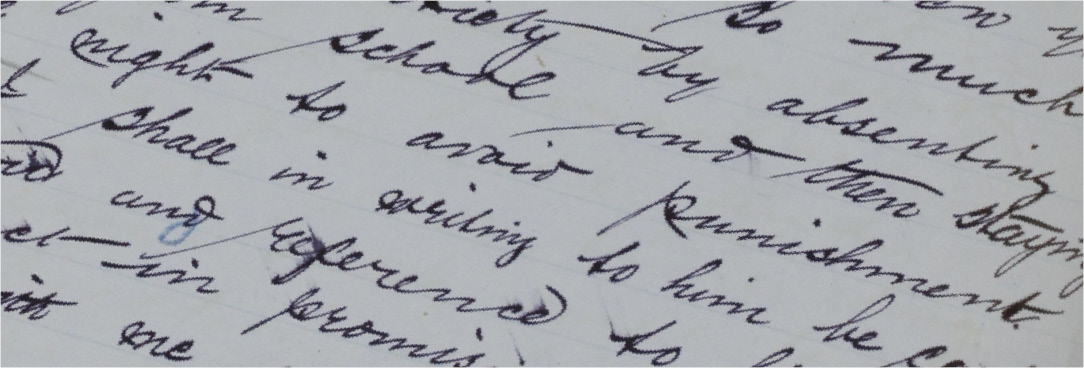

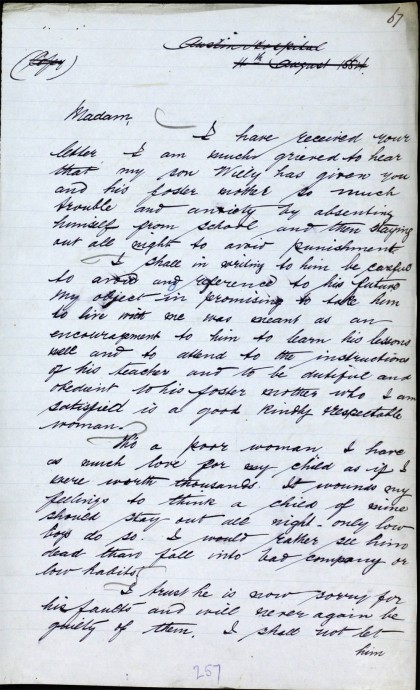

These records are similar to later case files in that they are problem-based, and hence generally negative. What is recorded is what is wrong with the mother that she is unable to provide for her own children. The comments or contact page is little better. We read there what other people say about the mother: clerks in the office describe face to face communication when mothers come in to seek contact with their children or obtain information; occasionally someone of influence in the community attempts to intervene on a mother’s behalf; or, more usually, a policeman, sent to enquire following an application to have a child home released, reports on what he has found. The mother’s voice in such documents is highly mediated indeed. Even when a clerk or policeman claims to be quoting a mother, the quote is taken out of context, designed to support whatever conclusion the reporter is trying to justify.

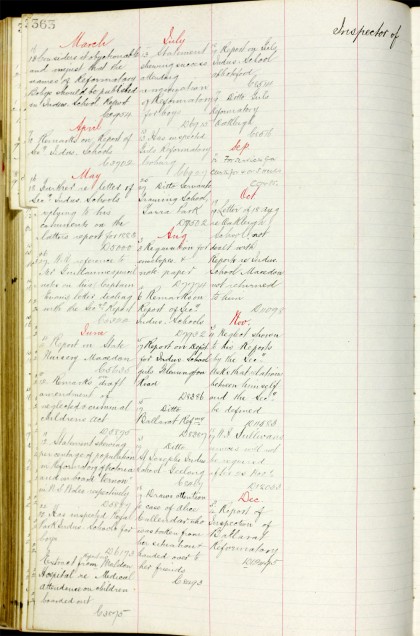

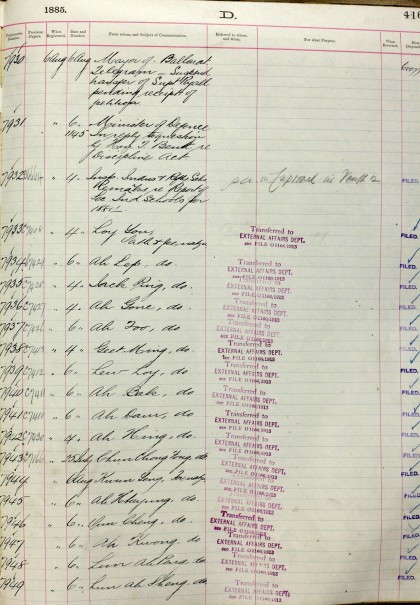

Chief Secretary’s Correspondence

Despite its high degree of decentralisation, or perhaps because of it, a system as large as this generated far more documentation than is retained in the ward registers. Because the Industrial Schools Department and later the Neglected Children’s Department and the Children’s Welfare Department were in fact nested in the much larger Chief Secretary’s Department, correspondence and other related documentation can be found among a range of other records related to the very diverse responsibilities which that office had.[5] There are grand indexes with neat headings like Infant Life Protection[6] and Industrial and Reformatory Schools (a heading which survives long after the buildings themselves have disappeared) but the index directs the researcher to an item in a trail of correspondence. In line with nineteenth century recordkeeping practices, the entire correspondence trail was filed according to the number of the final item. The indexes associated with these recordkeeping systems lead to entries in registers through which the trail of correspondence can be retraced to arrive at the final item number and thereby locate the item in the actual correspondence series. Sometimes it is easier to simply order a box where you think the item you are after might be included, then make your way through all the material it contains. There is no guarantee that this tactic will produce the specific piece you were after, but it will almost always produce other files that relate to child welfare matters.

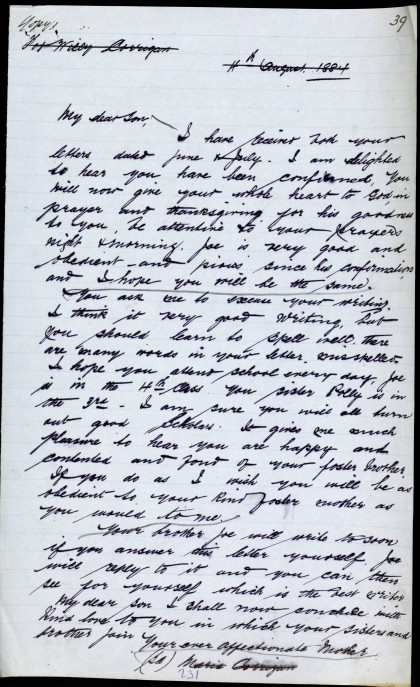

It is in these sources that the voices of mothers are to be found, for filed away here are the letters which they wrote on their own behalf. The correspondence files also give some insight into the boarding-out/foster care system and its place in the broader community. Here also is a second group of women, foster mothers, who in a way are also clients of the welfare system. Somewhere there are probably traces of the correspondence generated by the ladies’ committees, but that is a treasure yet to be located. Nell Musgrove is the only historian, so far, who has made systematic use of these records, and her work makes clear that the mothers who emerge in them bear a closer resemblance to Christina Twomey’s sympathetic descriptions than to the punitive assumptions on which the system was based.

This material shows the ways in which mothers worked around the intentions of the legislation to get temporary care for their children and to negotiate their release when their immediate need had passed. It shows members of the visiting committees assessing competing views as to the fitness of foster parents. Mothers wrote seeking to portray their families as upstanding, their partners as having overcome whatever problems had drawn them into poverty in the past. They also protested their separation from their children, demanding to be given reasons why they were being kept apart. There are also instances where mothers expressed their gratitude for the care that their children were receiving, even if such letters were filled with longing for the child who was away from their care. There are letters too from children attempting to make contact with the mothers from whom they had long been separated.[7]

The structure of Victoria’s boarding-out system was admired both nationally and internationally. Politicians in other colonies admired its economy, because although the foster mothers were paid, there was little in the way of central overheads. Advocates of boarding-out admired its demonstration of the value of engaging ‘motherly’ women to both care for and supervise what they liked to describe as ‘children of the state’. However, I would like to posit another reason why the system, with all its harshness, had some admirable features: namely, the woman-to-woman interaction which was at its base. Ladies’ committees were drawn from local benevolent associations, and brought with them all the prejudices that such a philanthropic approach encoded. Yet, many of the members were also mothers, and at some key moments we can see their identity as mothers slipping through and facilitating policy change. I would like to end by proposing three of their significant achievements.

1. Members of the ladies’ committees could recognise a happy child. Hence they became fierce defenders of boarding-out. When opponents committed to the older institutions depicted that model as being more efficient, as providing more consistent training and allowing for a greater paternal influence, the ladies’ committees responded that the children who were boarded out looked happier. When governments suggested cutting the boarding-out allowance as an economy measure, they went into battle, even, in some cases, threatening to strike, arguing that the happiness of the children should be above government cost-cutting.

2. They were prepared to innovate. Faced with the problem of young single mothers who were not only unable to support but also to mother their infants, they came up with a scheme which boarded both mother and child out with an experienced foster mother, whose task it was to mother them both. Although this scheme appears to have produced no reduction in infant mortality, for those who survived it did cement the mother-child bond. Although the child may still have spent substantial periods of its life in care, in adulthood it was far more likely to have continuing contact with its mother (and almost certainly its foster mother) when wardship ended at eighteen.

3. Thirdly, and most importantly, they were able to identify with at least some of the mothers who were threatened with the loss of their children through poverty. It was ladies’ committees which questioned the wisdom of paying a foster mother when a similar amount paid to the child’s own mother would mean that they could stay together. This revolutionary change, pioneered at the instigation of mothers at the Brighton orphanage, slipped into the government system from the 1880s. It went against all the assumptions of conventional charity, yet to the ladies’ committees it had an obvious appeal, and the more they saw of the happiness of children who were boarded out to their own mothers in this way, the more fiercely they defended the practice when it came under attack. By the mid 1890s more wards were boarded out with their mothers than with strangers, laying the basis for the social security schemes that would be established to assist mothers in this way from the 1930s on. Unfortunately this practice too is under-documented (or the documentation has yet to be found) but it should be celebrated as evidence again that poor women actively argued that their ability to mother should not be judged by their ability to generate an income.[8]

For a researcher with the time there is clearly more to be found in this rich resource, but to this point what is already clear is the strength of the mother-child bond, and the lengths both parties would go to maintain and restore it.

Endnotes

[1] C Twomey, Deserted and destitute: motherhood, wife desertion and colonial welfare, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2002.

[2] Victorian Ombudsman, Investigation into the storage and management of ward records by the Department of Human Services, March 2012, available online (accessed 10 July 2012). To be fair, the paucity of wardship files that have survived to the present day is a legacy of inappropriate recordkeeping policies that have a long history. The Final report of the Royal Commission on the State Public Service, published in 1917, contained an Appendix, ‘The Departmental Record Systems. Report by Mr. H. O. Allan’. Allan described the recordkeeping systems in use at the various Victorian Government departments at the time, but his most scathing criticism was for the records created by the Department of Neglected Children, which he described as the worst he had seen. A major complaint was that there was no central file created about wards: ‘Every child’s history should be complete on main file, even when it is necessary to divide files. If an officer requires to trace a child’s history he will encounter the following difficulties: – He must (1) get the commitment, or mandate, as it is called; (2) [get the] boarding-out file; (3) [get the] transfer of child [file] from one home to another (perhaps the child’s case is embraced in a general report); (4) [get the] rate of pay file; (5) [get the] service file, i.e after boarding-out the child is placed in service.’ Allan also indicated that the department had ‘Just started to destroy old records’. See Victoria. Legislative Assembly. Papers presented to Parliament, Session 1917, vol. 2, no. 15, pp. 130-1. I am indebted to Charlie Farrugia, Senior Collections Advisor at PROV, for this information. For further details see his reference to the destruction of wardship records 1864-c.1935 in his entry on the PROV Wiki entitled Destruction of Victorian Public Records Before the Establishment of the Public Records Act 1973 (accessed 28 August 2012).

[3] N Musgrove, ‘”The scars remain”: children, their families and institutional “care” in Victoria 1864-1954’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2009.

[4] See PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 4527 Ward Registers (microfilm available in Victorian Archives Centre Reading Room). The detailed case files which survive to the present day are contained in PROV, VPRS 10071 State Ward Case Files, Single Number System. While these mostly date from the 1920s onwards there is some evidence to suggest that some of the earlier records were destroyed: see the PROV Wiki cited above.

[5] See PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 3991 Inward Registered Correspondence II, and VPRS 3992 Inward Registered Correspondence III.

[6] Children in care under Infant Life Protection were not made wards unless the parents became delinquent with their payments.

[7] Two categories added in the Neglected Children’s Act 1887 allowed for the care of children under sixteen found residing in a brothel or associating/dwelling with a prostitute (para. 21), and uncontrollable children (para. 23). Prior to 1887 these were defined as neglected children. In 1919 the Maintenance of Children Act added a new category, children without visible means of support. This was effectively a ‘poor law’ to prevent the ‘abandonment’ of children.Up until then, mothers and grandmothers sometimes went to great lengths to ‘abandon’ children because this was the only way to get them into the system if the family could no longer care for them in a crisis.

[8] For a fuller discussion of these points see S Swain, ‘The Victorian charity network in the 1890s’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 1976, available online at the University Library Digital Repository, The University of Melbourne (accessed 10 July 2012).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples