Last updated:

‘Losing the Plot: Archaeological Investigations of Prisoner Burials at the Old Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge Prison’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 10, 2011. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jeremy Smith.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This paper presents the results of archaeological investigations and historical research into the burials of all prisoners executed in Melbourne from 1880 onwards. Over the past fifty years the knowledge of the location of these prisoner burial sites had become confused or forgotten, and was not accurately represented in official records. Much of the confusion dates back to 1929 when, following the closure of the Old Melbourne Gaol, approximately thirty burials were exhumed and the remains relocated to Pentridge in chaotic circumstances.

Recent archaeological excavations at the Old Melbourne Gaol and former Pentridge prison have done much to disentangle the complex history of the prisoner burials and it can now be reported that all burial sites at the Old Melbourne Gaol and former Pentridge prison from 1880 onwards have been located.

This paper was written prior to 1 September 2011, when the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine announced the results of its DNA analysis of Pentridge remains. These remarkable findings are included here as a Postscript.

Background

In March 2002, archaeologists from La Trobe University, working at the Old Melbourne Gaol site, made a surprising discovery. They unearthed an intact coffin buried against a bluestone wall in the area of the former gaol hospital.[1] This unexpected find set in train a series of investigations into the history of prisoner burials at the gaol and at the former Pentridge prison in Coburg, which led to a number of significant outcomes, including the discovery of a ‘lost’ burial ground at Pentridge,[2] the recovery of the skull stolen from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1978, and the identification of the remains of Colin Ross, who was executed in 1922, exhumed and reburied in 1937, and pardoned in 2008.

The history of Melbourne’s prisoner burials is not a straightforward one. Following the closure of the Old Melbourne Gaol in the mid-1920s the remains of all executed inmates that could be located were exhumed, transferred to Pentridge, and re-interred in mass graves. The first of these relocations took place in April 1929, when the remains of approximately thirty individuals were exhumed in the grounds of a former Old Melbourne Gaol labour yard. In 1937, four additional coffins were unearthed in a different area, adjacent to the former gaol hospital, and were also taken to Pentridge for reburial.[3] Additionally, between 1932 and 1967 ten inmates were executed and buried at Pentridge.

A number of significant, if notorious, historical figures are among those whose remains were almost certainly moved from the Old Melbourne Gaol to Pentridge. Ned Kelly is recorded as being one, as is Australia’s worst nineteenth-century serial killer, Frederick Deeming,[4] and the ‘baby-farmer’ Frances Knorr.[5] However, despite the historical significance of many of the executed prisoners, the knowledge of the precise location of the burial ground at Pentridge was lost or forgotten. When the former Pentridge prison site was sold by the state government in 1999, the location of the burial ground could not be established with certainty, and an area adjacent to the east end of the D Division building – and which was known to contain the remains of Ronald Ryan (executed in 1967) – was wrongly designated as the likely location of all the burials.

The key event in the convoluted history of Melbourne’s prisoner burials took place at the Old Melbourne Gaol, shortly after its closure, in 1929. On 12 April the first of a number of graves was exposed during construction work for the extension of the Working Men’s College (now RMIT University).[6] The college had acquired part of the gaol property which had been used as a prison yard and as the burial area for inmates executed between 1880 and c. 1916. On 13 April 1929, the Argus published an article titled ‘Ned Kelly’s grave. Discovery in Old Gaol. Schoolboys seize bones’, which reported that:

When the steam shovel was lifting earth and stones last week Mr. H. Lee, of Lee and Dunn, the contractors for the building, had his attention directed to the name ‘E. Kelly’ carved in a stone in the wall, together with the imprint of a broad arrow. The excavation work was continued with the steam shovel, and the workmen kept a lookout for the coffin [which] was unearthed at noon yesterday. The edge of the shovel ripped off the lid of the coffin, which was made of redgum, and a skeleton was revealed.

As soon as this gruesome discovery was made a crowd of boys who had been standing round expectantly while eating their luncheons rushed forward and seized the bones. The workmen intervened, but in the scramble portions of the skeleton were carried off, including even the teeth. The grave and the coffin were still powdered with quicklime. After nearly 50 years the skeleton remained intact when it was unearthed.

Mr. Lee intends to hand the skull to the police for the medical school at the University… Another coffin was seen protruding through the broken earth near the same spot. Arrangements have been made for the disinterment of this and such others as may be discovered with due respect for decency. (p. 20f)

On 17 April, the Argus followed up this story with an article titled ‘Gaolyard graves. Stolen bones recovered. Reinterment at Pentridge’, which reported:

Following the warning given by the Chief Secretary (Dr. Argyle) on Monday that those who had removed the bones of the bushranger Ned Kelly from his grave in the Old Melbourne gaol yard, when it was opened last week during building operations, most of the bones were returned to officers of the Penal department yesterday. Many were returned by those who had taken them away, but others were recovered by detectives who investigated the case…

Since it has been established that the bones of executed criminals buried in the gaol yard have not been destroyed by the quicklime in which they were buried, it was decided by the State Cabinet yesterday to open the remaining graves, and remove the coffins to the Metropolitan Gaol at Pentridge. (p. 7h)

A further report in the Argus on 19 April quoted the Secretary of the Building Labourers’ Union, who confirmed that ‘apparently no attempt had been made to identify the remains, which had been placed in sacks about the works’.[7] Following the chaotic discovery and disturbance of the first graves, a professional undertaker was engaged to oversee the exhumation and re-interment of the remaining burials. The undertaker Josiah Holdsworth, of Lygon Street in Carlton, was assisted by Charles and Leslie Brown from the Melbourne General Cemetery.[8] The Argus report of 19 April stated that Holdsworth was in charge of works at the site and he had explained that all remains were to be placed in coffins and taken to Pentridge. Holdsworth was aware that sets of remains had already been relocated to Pentridge.

Two issues of particular significance emerge from the events at the Old Melbourne Gaol in April 1929. It is clear that the initial process of exhumation, the sorting and packing of bones, and their relocation to Pentridge was carried out in a disorganised manner, particularly in the week prior to the engagement of Holdsworth. It is possible that some mixing or commingling of remains took place during the exhumation process and while bones were ‘lying in sacks about the works’. At the same time, information about which remains had come from particular coffins and grave sites may have become confused. The theft of remains believed to be those of Ned Kelly on Friday 12 April and their recovery at the start of the following week may have resulted in the loss of some material or even the substitution of other bones.

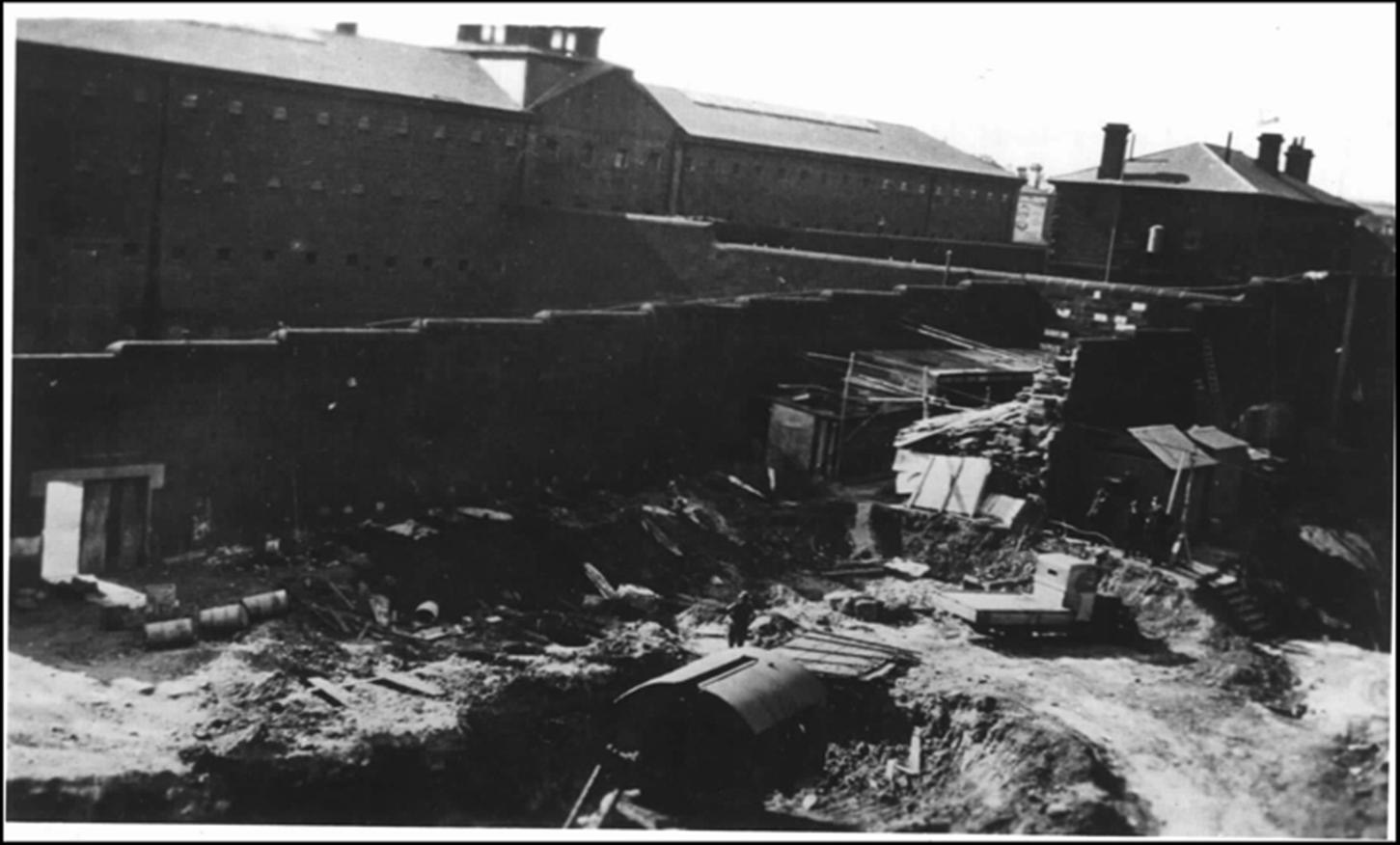

A remarkable image exists of the former Old Melbourne Gaol burial ground being disturbed in April 1929 (Image 1). The picture shows the dismantling of the southern bluestone wall of the yard. The bluestone blocks were destined for re-use in the construction of sea walls stretching from Brighton to Beaumaris as part of depression-era civic works. In the yard, the initials of each executed inmate and the date of his or her execution were carved into the wall adjacent to the burial plot. As a result, at three known places along the sea wall it is possible today to see clusters of bluestone blocks with carved initials and dates (Image 2). In all cases the initials and dates correlate with the name of an inmate and the date of execution.[9] The April 1929 image also portrays the ‘scramble’ so vividly reported in the Argus. Open grave sites can be seen, and coffins and coffin lids lie strewn across the site. On the left-hand side of the image a pile of square wooden boxes is visible. In 2009, what are probably the very same boxes were discovered in a mass grave at Pentridge, containing prisoner remains.

The exhumations that took place in the former yard of the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1929 were undertaken to allow extensions to the Working Men’s College. In 1937 it was decided that the four burials located in the grounds of the gaol hospital should also be exhumed and transferred to Pentridge. The hospital grounds had been used for burials from approximately 1912 until 1924.[10] We now know that there were five, rather than four, coffins buried in the grounds of the hospital in the early twentieth century and that one of these was not found by the team engaged to relocate the burials in 1937. It was this one remaining burial which was unearthed by the La Trobe University archaeology team, sixty-five years later in March 2002, as they were monitoring landscaping works being conducted by RMIT.[11]

Excavations at Pentridge

Following the work by the La Trobe University team, and the developing understanding of the sequence of exhumations at the Old Melbourne Gaol, Heritage Victoria’s attention turned to the former Pentridge prison site, which had recently been sold by the government to private developers. Historical evidence suggested that Pentridge was the location for approximately forty-four burials: thirty sets of remains transferred from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1929, an additional four burials relocated in 1937, and ten burials of inmates executed and buried at Pentridge between 1932 and 1967.

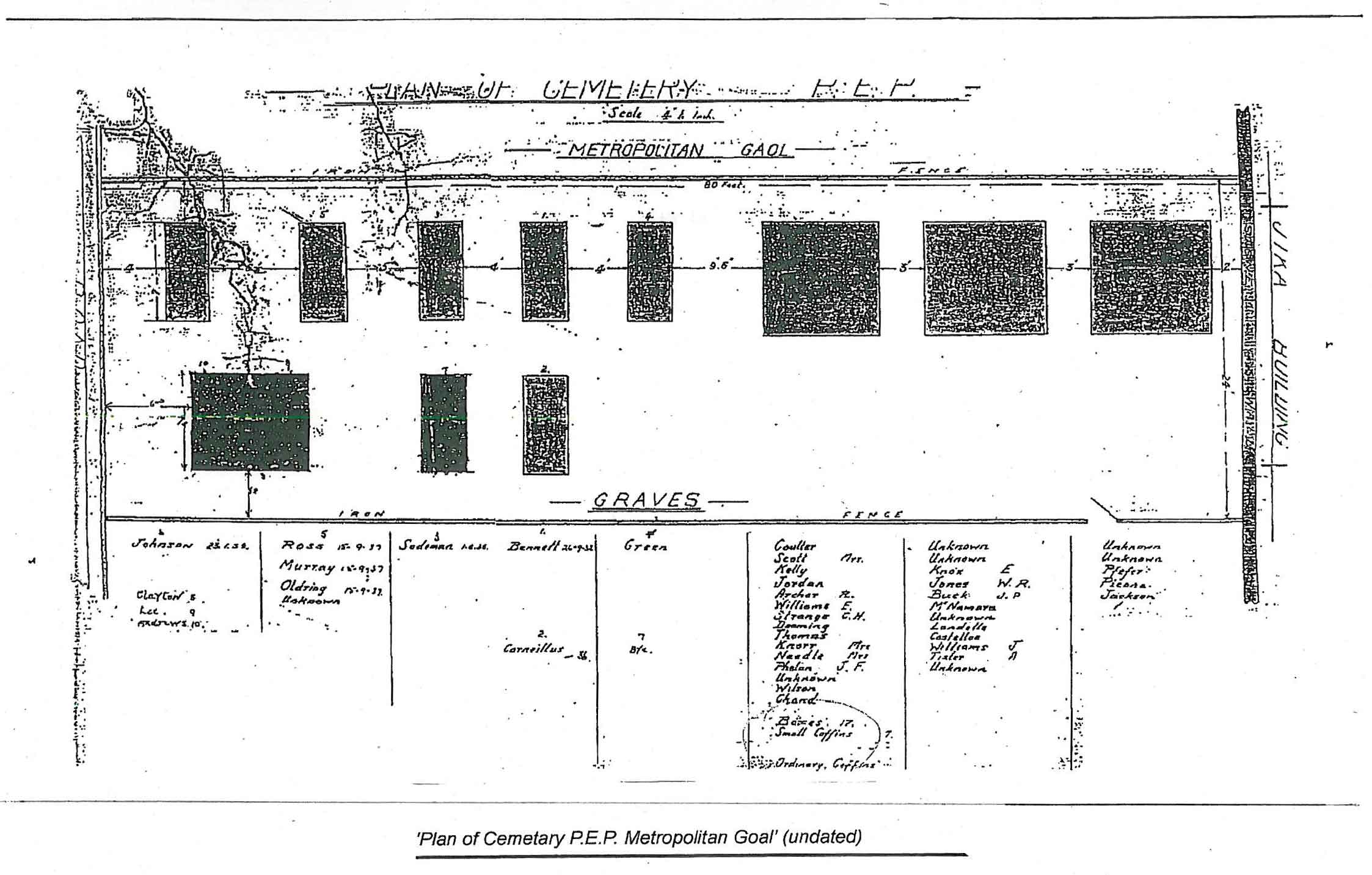

As part of the research into the history of the single burial unearthed at the Old Melbourne Gaol site in 2002, the La Trobe team obtained copies of a couple of different versions of a plan that seemed to show the layout of a burial ground at Pentridge. One version of the plan was obtained from a Department of Corrections file.[12] A similar plan, reproduced here (Image 3), was obtained from a National Trust staff member and shows a rectangular area (with marked dimensions of 80 feet x 24 feet) located within an iron fence and with a gate in one corner. Two things are immediately interesting about this plan. The first is that the burial location of Ronald Ryan (executed in 1967) is not shown; the second is that the burial area is of a very different size and shape from the triangular-shaped area adjacent to the end of D Division, which had long been regarded as the Pentridge cemetery site, and which was known to contain Ryan’s remains. What the plan does show are three large mass grave sites containing individuals from the 1929 relocation, a smaller mass grave possibly relating to the 1937 re-interments, and individual plots of the nine inmates who were executed and buried at Pentridge between 1932 and 1951.

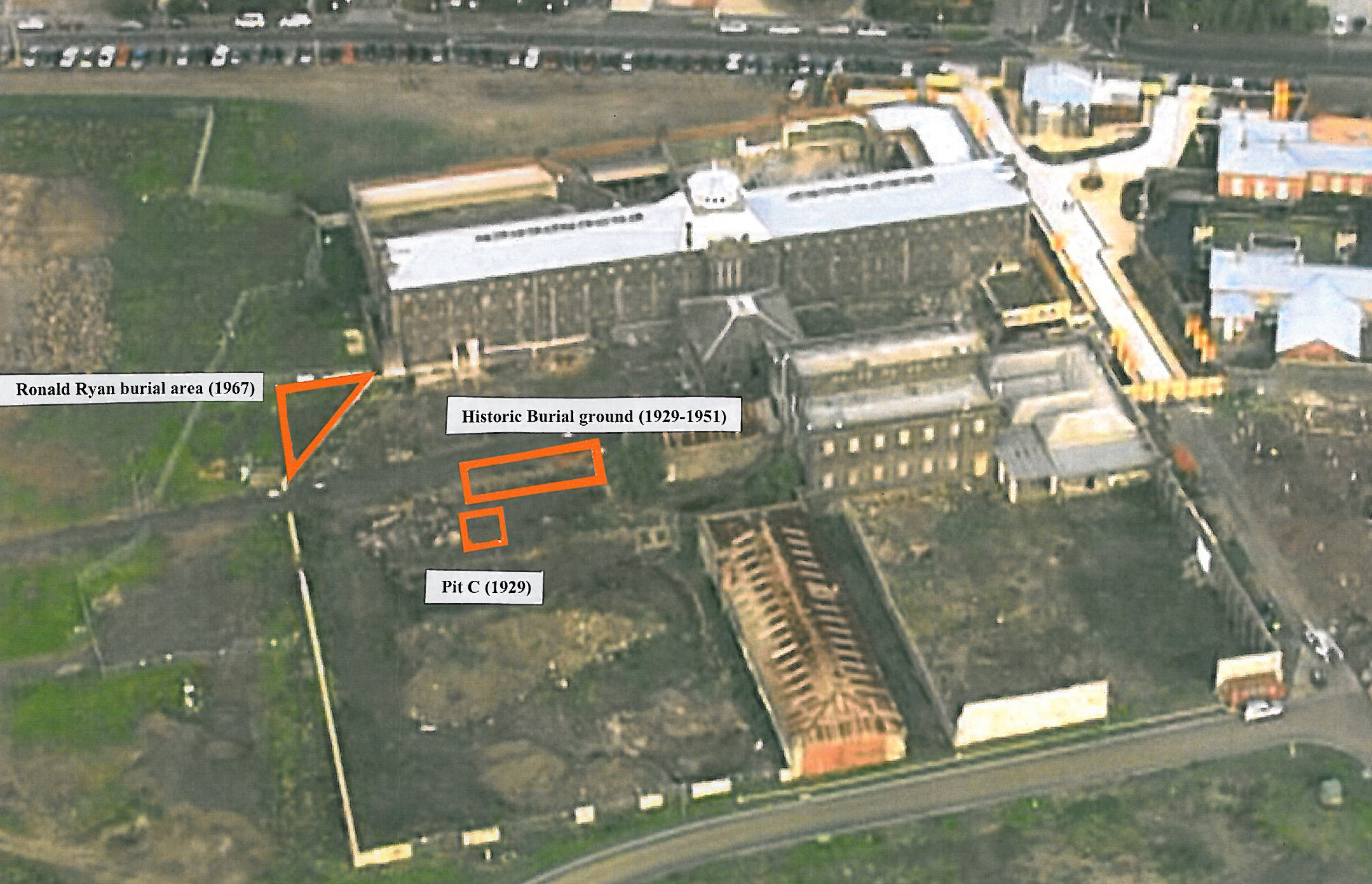

So in 2006, based on the evidence of this plan and suggestions from former prison staff that there may have been an earlier burial site separate from that of Ryan’s, Heritage Victoria determined that archaeological testing of the Pentridge cemetery site was warranted.[13] The aim of the testing was to confirm that all of the former Old Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge burials could be accounted for, and to define the precise location and extent of the burial area. In September 2006, consultant archaeologists Terra Culture, led by senior archaeologist Catherine Tucker, conducted detailed testing across the cemetery site. They demonstrated conclusively that this area contained only one burial, believed to be that of Ronald Ryan.[14] It was then apparent that the burial locations of as many as forty-four individuals, including some of the most significant figures in Australia’s criminal and general history, were not known.

What followed was a detailed program of historical research, through a range of prison and other records, to try and establish the location of the Pentridge burial ground. The most important breakthrough came from an examination of a series of aerial images from the 1955 ‘Airspy’ series (Image 4). One image covered the Pentridge prison site which, when magnified, showed a rectangular yard, unused and overgrown with weeds, enclosed by a corrugated iron fence (Image 5). The dimensions of the yard matched the size and shape of the burial ground shown in the old prison records plan.

Terra Culture were again engaged to conduct archaeological investigations in the area identified in the aerial image. Over the course of a few weeks they located the grave sites of the nine prisoners executed and buried at Pentridge between 1932 and 1951 and a single mass grave, believed to contain the remains of the four individuals relocated from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1937. At this time no actual disturbance to the graves or exhumations took place, as the archaeologists’ brief was only to establish the location of the burial ground. The burials relocated from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1929 were not identified as part of this phase of testing, and it was noted that the area at the western end of the site (the area indicated on the burial plan as being the location of the three large mass graves) had been extensively disturbed by mid-twentieth-century sewerage and drainage services. The satisfaction that the burial ground had been successfully located was tempered by the likelihood that the earliest burials containing significant figures such as Kelly and Deeming had been disturbed and removed during building works in the grounds of Pentridge in the 1960s (Image 7).

In March 2008, following discussions with the Department of Human Services[15] and the Office of the State Coroner,[16] it was determined that the burials located by the Terra Culture team should be exhumed.[17] The archaeologists’ brief was to establish whether the individuals interred in the burial ground at Pentridge could be identified, and to record all significant features of the burials. Any remains that could not be positively identified were to be delivered to the coroner’s office. It was also determined that any remains that could be identified were to be exhumed from the burial ground and re-interred in the area at the end of the D Division building (where Ryan had been buried until his remains were exhumed and handed to his family in early 2008). The site owners, Pentridge Village, made a large area of land available in this part of the site for the reburial of all recovered remains, and for the development of an appropriately designated, managed and interpreted cemetery area.

During March 2008 the Terra Culture archaeologists conducted detailed investigations and exhumation work across the former burial ground.[18] The remains of the nine inmates executed at Pentridge between 1932 and 1951 were identified. These remains were found in individual burial plots and in separate coffins with metal name plates.[19] As all of these burials were clearly identifiable there was no requirement for the remains to be forwarded to the coroner, and they were re-interred in the designated burial area adjacent to the D Division building.

As they continued their investigations, the archaeologists also located and exhumed remains believed to be those transferred from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1929 and 1937. The first of these to be uncovered was a small plot containing four coffins. It was likely these were the remains moved from the grounds of the gaol hospital in 1937. The prison records plan lists Ross, Murray, Oldring and one ‘Unknown’ as being re-interred in this small mass grave. However, as there were no name plates attached to any of the coffins it was not possible to identify any of the individuals at the time of exhumation, so these remains were delivered to the coroner’s office.[20]

At the western end of the burial area, in the part of the site shown on the plan as the location of the three mass graves containing the prisoner remains relocated from the gaol in 1929, the archaeologists found only two mass graves. These graves had not been identified during their earlier testing phase because they were located at a greater depth than the other burials.

One of the mass graves contained twelve wooden coffins and was designated by the archaeologists as Pit A. The condition of the coffins and their contents varied greatly, but in many cases was good. A few metres to the west of Pit A, the second mass grave was found and was designated as Pit B. Pit B was slightly smaller than Pit A and contained only five coffins. Generally, the condition of the Pit B coffins and remains was comparable with the material found in Pit A, suggesting that they were associated with the same process of relocation. Large amounts of lime had been packed into the coffins in both of the mass graves, presumably to accelerate the deterioration of the remains. However, inside the coffins the lime had set as a solid mass or cast and had instead preserved the bones. No name plates or identifying features were located on or within any of the coffins in either of these mass graves. Accordingly, the remains from both Pit A and Pit B were exhumed and delivered to the coroner.

Despite conducting extensive investigations within the area of the historic burial ground, and particularly in the direct vicinity of the two large graves, the third mass grave (as shown on the burial plan) could not be located. By the end of March 2008, a large rectangular area measuring more than 30 m x 10 m had been excavated down to the undisturbed subsoil, to prove that there were no more burials in the area designated on the prison records plan.

In general, the positions of the graves accorded well, if not exactly, with the details shown on the historic plan: the graves were located in two lines running on an east-west orientation, and the three burials of Clayton, Lee and Andrews were found directly adjacent to each other. However, the burials of almost all of the other twentieth-century prisoners were not shown in their correct relative locations; only Sodemann’s burial was correct. Other features shown on the plan, such as the iron perimeter fence, were also demonstrated as being correct by the archaeologists, who found evidence of the fence-line structure. The main discrepancy between the plan and the archaeological findings was the absence of the third mass grave, although there remained the possibility that this feature had once existed, as shown on the plan, but had been disturbed or relocated in the mid-to-late twentieth century.

It is significant to look in detail at the numbers of burials discovered in the two large mass graves. Pit A contained twelve burials, and Pit B contained five. These numbers accord exactly with the details shown for two of the mass graves on the burial plan. The mass grave shown on the plan as the middle of the three plots is listed as containing twelve burials.[21] The plot at the end of the burial ground lists five names.[22] The twelve burials in Pit A seem generally to consist of inmates executed at the Old Melbourne Gaol in the period 1889 to 1904, while the five burials in Pit B are more likely to be from the period 1912 to 1916. There were no executions in Melbourne between 1905 and 1911. In some cases it is possible to speculate on the identities of those listed as ‘Unknowns’, based on the list of Victorian executions. For example, the names of William Colston (executed at the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1891) and George Syme (executed 1888) do not appear on the burial plan, although it is likely that their remains were included with the material exhumed and relocated in 1929.

As a result of the Terra Culture fieldwork it was considered likely that the large mass grave that remained unaccounted for was the largest plot, and would have contained approximately fifteen burials, including the oldest sets of remains dating back to 1880, but that the other two mass graves from 1929 had been found.

Ned Kelly’s Skull

Throughout 2008 there was considerable media interest in the investigations at Pentridge. Unsurprisingly, much of this attention focused on the search for Ned Kelly’s bones. The media coverage resulted in many enquiries to Heritage Victoria, with some unexpected results. In mid-2008 Mr Tom Baxter contacted Heritage Victoria, claiming that he knew the location of the skull that was stolen from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1978. The skull, which was on display at the gaol at the time of the theft, was one of four that had been given to the National Trust (the managers of the gaol) in 1971 by the Institute of Anatomy in Canberra. It is believed that the ‘Baxter skull’ and three others were given to Colin McKenzie, the founder of the Australian Institute of Anatomy, soon after the 1929 exhumations took place. One theory suggests that Mr H Lee, whose firm of Lee and Dunn, building contractors, worked in the gaol yard in April 1929, collected the skulls – thought to be those of Kelly, Deeming, Knorr and Needle – when their coffins were first exposed (see excerpt from the Argus, 13 April 1929, quoted earlier).

When he contacted Heritage Victoria, Mr Baxter asked whether Ned Kelly’s remains had been discovered, and what plans there were for the reburial of any identified remains. Although it was not possible for these questions to be answered at that time, Mr Baxter was encouraged to contact Heritage Victoria again in the future to discuss the progress and results of the project. It was also suggested to him that he should consider handing the skull in to the coroner, as it was potentially a significant item in its own right and might assist with the identification of other remains recovered from Pentridge.

In November 2008 Heritage Victoria invited Mr Baxter to visit the site of the Ann Jones Inn, Glenrowan, which was undergoing archaeological investigation. He was again encouraged to consider releasing the skull to the appropriate authorities. A year later, Mr Baxter contacted Heritage Victoria and stated that he had decided to deliver the skull to the coroner, and he subsequently did so on 11 November 2009.[23] The Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine was able to establish that the skull was that of a robust adult male and commenced DNA analysis.

Colin Ross

Another significant outcome from the project concerns Colin Campbell Ross, who was convicted of the notorious ‘Gun Alley Murder’ on 25 February 1922 and executed two months later. On 27 May 2008, following forensic investigations which discredited key police evidence, Colin Ross received a posthumous pardon from the Governor of Victoria. On hearing of the discovery of the burial ground at Pentridge, the descendants of Colin Ross asked whether his remains could be identified and whether they could be returned to the family.

Colin Ross was the second-last inmate executed at the Old Melbourne Gaol, and historical evidence suggests that he was one of the five individuals originally buried in the grounds of the gaol hospital. It was likely, as the burial plan suggests, that his remains were located in the small mass grave at Pentridge that contained four burials relocated from the gaol in 1937, and so the chances of making a definitive identification were strong.

On 1 September 2010, the coroner issued a determination stating that the remains of Colin Campbell Ross had been successfully identified, and directing that his remains be released to the senior next of kin.[24] The cremated remains of Colin Ross were handed to his family at a ceremony at the Old Melbourne Gaol in October 2010.

The Missing Mass Grave

While the recovery of the Baxter skull and the identification of Ross’s remains were proceeding, a final discovery was unfolding. On 23 February 2009, Heritage Victoria was contacted by the Pentridge site owners to inform them of the unearthing of additional burial boxes located not far from the historic cemetery area. The boxes had been uncovered during site trenching work, although the burials had not been disturbed. After inspecting the site it was clear that the exposed feature consisted of more than just one or two coffins and was in fact another mass grave. Following consultation with the coroner’s office and the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, Heritage Victoria’s historical archaeology unit agreed it would investigate the discovery and manage any burials and human remains in accordance with the protocols previously established for the Terra Culture work.[25]

The archaeologists worked throughout March 2009 to exhume and record the burials from what proved to be the largest of the mass graves at Pentridge. The plot (designated Pit C) contained two layers of burials, totalling twenty-four burial boxes. In some cases the remains of one individual were found to be spread across more than one box, with bones from the upper body located in one box and bones from the lower part in another. It is likely that the partial or nearly complete remains of approximately fifteen individuals were contained within these twenty-four burial boxes. The top layer of Pit C consisted of eleven wooden boxes, three medium-sized coffins and one small coffin (Image 8). The bottom layer contained six wooden boxes and three coffins (Image 9). It is almost certain that this was the missing plot that had not been found during the archaeological investigations a year earlier. Intriguingly, the mass grave was not located in the area shown on the historic burial plan, but was discovered approximately thirty metres away from its recorded position. It is possible that this mass grave was originally located within the burial ground, as shown on the plan, but was disturbed and relocated, perhaps during the 1960s when drainage pipelines were installed across this part of the site.

Pit C is likely to have been the first mass grave established at Pentridge, containing the remains of inmates executed from 1880 to the mid-1890s, and it probably represents the initial phase of exhumation and relocation work undertaken in chaotic circumstances by the building contractors prior to the appointment of the undertaker Holdsworth. The Argus reports the initial discovery of the ‘Kelly’ grave site taking place on Friday 12 April 1929, and Holdsworth is in charge on site by the following Friday 19 April, so it is almost certain that the reburial of the oldest set of remains in the first mass grave took place at Pentridge between 15 and 18 April 1929.

The conditions of reburial noted in Pit C differ markedly from those observed in Pits A and B, further suggesting that Pit C contained the first burials relocated to Pentridge prior to Holdsworth’s appointment. Significantly, Pit C was found to contain a large number of wooden boxes, which had been used for the reburial of human remains. It is likely that the contractors picked surviving bones from the remains of deteriorated wooden coffins and placed them in the boxes for relocation and reburial at Pentridge. Holdsworth, as a professional undertaker, may have insisted on the use of new coffins, as seen in Pits A and B.

Research on the boxes found in Pit C has shown that they were originally used for a range of industrial purposes. Four of the boxes were made for axe handles, imported from the American Mann Edge Tool Company (Image 10). Two others were manufactured in Australia for bottles of lamp kerosene by the Commonwealth Oil Refineries (Image 11). An annotation which reads ‘Boxes: 17 Small Coffins: 7‘ appears on the historic burial plan, directly beneath the names listed in the largest of the mass graves (see Image 3 above). Exactly seventeen boxes and seven coffins were identified by Heritage Victoria in Pit C (Images 10 and 11). This further supports the identification of this feature as the mass grave of the first inmates exhumed at the Old Melbourne Gaol and relocated to Pentridge, probably at the start of the week of 15 April 1929, as does the discovery in one of the boxes of paper fragments of the Argus dating from 3 April 1929 and 12 April 1929.

During post-fieldwork analysis in Heritage Victoria’s Conservation and Research Centre, very fine lead-pencil markings were noted on the lids of a small number of the Pit C burial boxes. The details written on the three lids were: John Thomas Phelan; William Colston 91; and John Conder 28-8 94. Phelan’s name is shown on the historic burial plan, and his execution date in Melbourne in 1891 places him within the chronological range expected for the earliest of the mass graves. Neither Colston’s nor Conder’s name is listed anywhere on the burial plan, but their dates of execution (Colston in 1891 and Conder in 1893) place them in the middle of the range of dates noted for the other burials in the mass grave. It is possible that Colston or Conder could be the ‘Unknown’ listed on the plan between the names of Phelan and Wilson. The name ‘Coulter’ does appear on the burial plan, even though no-one of that name was ever executed in Victoria. Interestingly the date of Conder’s execution is written on the lid as 28-8 94, but Conder was actually executed on 28 August 1893.

Final Steps

On 2 September 2010, the State Coroner announced that she was satisfied that the human remains recovered from the mass graves at the former Pentridge prison site were the remains of judicially executed prisoners, originally interred at the Old Melbourne Gaol, and that no formal inquest was required.[26]

In October 2010, the (then) Attorney General, Robert Hulls, announced funding for the forensic profiling and testing of all of the former Old Melbourne Gaol remains that were relocated to Pentridge in 1929 and 1937.[27] Forensic investigations are currently underway but it is not yet known whether it will be possible to obtain viable DNA samples from the remains, which in many cases are highly deteriorated. If DNA can be obtained from the Pentridge remains, and if family descendants choose to come forward and submit samples for cross-referencing, definitive identification of some or all of the remains may be possible. In the next few months, following the completion of the forensic work, it is likely that the remains will be reburied, in individual plots. This will probably take place at the former Pentridge site in the area set aside by Pentridge Village, where the remains of the nine other inmates executed and buried at Pentridge between 1932 and 1951 (whose identities are known) have already been re-interred. This space will not celebrate the lives of those who are buried there, but they are, by any reckoning, significant historical figures and a site interpretation scheme will present the stories of the Old Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge burials.

Although the final project outcomes are still to come, much has already been achieved. The remains of Ronald Ryan and Colin Ross have been formally identified by the coroner, and returned to their families for private burial. The skull that was stolen from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1978, and believed by some to be that of Ned Kelly, has been handed in and is now undergoing analysis. At the former Pentridge prison site in Coburg all burials are now accounted for and the burial ground that was last used in 1951, and seemingly faded from general memory soon after, has finally been rediscovered.

Postscript

On 1 September 2011, the Attorney General Robert Clark announced the results of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine’s investigations into the Pentridge remains. The team had made remarkable findings relating, firstly, to the skull handed to the coroner by Tom Baxter and, secondly, to the remains of Ned Kelly.

The forensic team obtained DNA from more than thirty sets of the Pentridge remains. Samples of DNA were also taken from the ‘Baxter’ skull, and from the great-grandson of Ned Kelly’s sister.

The most significant findings were:

- The ‘Baxter’ skull is not that of Ned Kelly, but its DNA matches another of the Pentridge burials. Odontological analysis (which assesses teeth and facial bone structures) and comparisons with death masks suggests that the skull is that of Frederick Deeming.

- The DNA of the Kelly relative matched with the remains from one of the axe boxes in Pit C (see Image 10 above). These are the remains of Ned Kelly. Surprisingly, the skeleton was found to be almost complete, missing only the majority of the skull, a few vertebrae and some smaller bones. The discovery of part of Kelly’s skull in the burial proves that a single intact skull no longer exists.

- The bones of Ned Kelly showed clear evidence of the injuries he received at the Glenrowan siege in June 1880. A round hole caused by a gunshot wound was visible in the top of his right tibia and two metal gunshot pellets were lodged inside the bone. There was clear evidence also of gunshot wounds to the left arm and right foot, consistent with the injuries reported by Dr Andrew Shields, who tended Kelly after his capture.

The results of the forensic analysis confirm some of the theories associated with the Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge burials, but throw others into question. For example, the Argus stories from April 1929 that report the ransacking of Kelly’s grave are belied by the largely intact condition of his burial, which is among the most complete of all the Pentridge remains. It seems that the ‘crowd of boys’ who ‘rushed forward and seized the bones’ targeted the wrong burial. However, the theory that Pit C was likely to contain the remains of the first burials exhumed from the gaol (including Kelly’s) has been shown to be correct.

Now that Ned Kelly’s remains have been identified, Heritage Victoria has begun discussions with relevant parties, principally the family, regarding their appropriate reburial.

Endnotes

[1] See R Wright, ‘Report on burial; designated F85 from the former Police Garages on Russell Street, Melbourne’, Report to Heritage Victoria and RMIT University Property Services, April 2002; G Hewitt, Archaeological investigations at the former Police Garage site, Russell Street, Melbourne. Final report, Part 1, Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, February 2003; G Hewitt and R Wright, ‘Identification and historical truth: the Russell Street Police Garage burials’, Australasian historical archaeology, vol. 22, 2004, pp. 57-70; K Zygmuntowicz, ‘Old Melbourne Gaol Hospital and Warders’ Yards: research on the history of the Police Garage site Russell Street, Melbourne’, prepared for RMIT Asset Management Group and Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, May 1998.

[2] The burial grounds contained the remains of all inmates executed in Melbourne between 1880 and 1951, except for Edward Leonski, an American serviceman who was executed at Pentridge in 1942. His remains were returned to the American military and he was buried on the island of O’ahu, Hawaii.

[3] It is likely that the first burials within the Old Melbourne Gaol took place in 1865, following the enacting of the Criminal Law and Practice Statute 1864. This statute required the burial of executed inmates within the grounds of the prison in which they were last incarcerated. Eighteen executions and presumably burials took place at the gaol from 1865 to 1879 inclusive. The locations of these burials are not known, but it is possible that they were interred in a large square labour yard in the south-west corner of the gaol precinct (see The Argus, 17 April 1929, p. 7). See also MMBW Detail Base Plan 1022, 1895, and MMBW Detail Plan 1022, c. 1910, Maps Collection, State Library of Victoria (821.09E). The passing of the Crimes (Capital Offences) Act 1975 (Victoria), which abolished capital punishment, means that the provisions of the 1864 Act no longer apply.

[4] Frederick Bailey Deeming was executed in 1892 for the murder of Emily Mather in Windsor. It is likely that he was also responsible for other murders in England and South Africa, where bodies were discovered in houses he had occupied. See R Weaver, The criminal of the century, Arcadia/Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, 2006, and PROV online exhibition Bigamy, theft and murder: the extraordinary tale of Frederick Bailey Deeming.

[5] J Main, Hanged: executions in Australia, BAS Publishing, Seaford, 2007, pp. 128, 248.

[6] It is likely that the authorities did not expect to find the burials largely intact, owing to the practice of adding quicklime in order to hasten decomposition. Ironically, the lime may have had the opposite effect, contributing to the preservation of coffins and remains. See PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 3992/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence III, Unit 1858, File W4499.

[7] ‘Gaol skeletons. Delay in removal. Builders’ labourers cease work’, The Argus, 19 April 1929, p. 9b.

[8] D Chambers, The Melbourne General Cemetery, 150 years, Hyland House, Melbourne, 2003, p. 201.

[9] The bluestone wall is on the Victorian Heritage Register, no. H2206. See ‘Former Old Melbourne Gaol burial markers’, in Victorian heritage database (accessed 18 August 2011).

[10] See advice from Joseph Akeroyd, Inspector General of Penal Establishments, to Chief Commissioner of Police regarding location of five burials in hospital grounds, PROV, VPRS 3992/P0, Unit 1858, File W4499. Initially there were difficulties locating the burials in the hospital grounds and a retired former chief warder was asked to provide advice. See also The Argus, 17 April 1929, p. 7.

[11] See Hewitt and Wright, ‘Identification and historical truth’. The remains exhumed by the La Trobe team were re-interred at Fawkner Cemetery on 26 April 2002.

[12] One version of the plan was obtained from the Department of Corrections, see K Zygmuntowicz, ‘Old Melbourne Gaol Hospital and Warders’ Yards’, appendix D.

[13] C Tucker (Terra Culture), Pentridge prison burial ground archaeological assessment, Report to Pentridge Village and Heritage Victoria, July 2006.

[14] Following a request from his family, Ronald Ryan’s remains were exhumed in December 2007. After confirmation of his identity, the remains were given to his family in early 2008.

[15] In Victoria, the Department of Human Services administers the Cemeteries and Crematoria Act 2003.

[16] In Victoria, the Office of the State Coroner and the Coroner’s Court administer the Coroners Act 1985. On 1 November 2009, the Coroners Act 2008 came into operation.

[17] The Coroners Act 1985 requires that all unidentified human remains must be made available to the coroner, who will determine whether the death(s) is ‘reportable’ and whether an inquest(s) is needed.

[18] The Terra Culture work was conducted under the terms of Department of Human Services Exhumation Licence No. 65/2007. The field team was assisted by Dr Soren Blau, forensic anthropologist, from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (VIFM). In collaboration with VIFM and Heritage Victoria, the team developed and followed detailed protocols to ensure the careful and thorough exhumation of all burials, the avoidance of commingling of remains, and detailed recording of site evidence.

[19] Remains were those of David Bennett (executed 26 September 1932), Arnold Sodemann (1 June 1936), Edward Cornelius (22 June 1936), Thomas Johnson (23 January 1939), George Green (17 April 1939), Alfred Bye (22 December 1941), Robert Clayton (19 February 1951), Norman Andrews (19 February 1951) and Jean Lee (19 February 1951).

[20] S Blau, Human skeletal remains recovered from Pentridge: 2009 forensic anthropology report, Human Identification Services, Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, June 2009. On Arthur Oldring see K Close, ‘The demise of Bicycle George: a life of crime’, Provenance, no. 9, 2010.

[21] Spelling of Landells on the burial plan is incorrect. Robert Ladells was executed on 16 October 1889.

[22] Spelling of Pfefer on the burial plan is incorrect. Joseph Pfeiffer was executed on 29 February 1912.

[23] The circumstances of Tom Baxter’s acquisition of the skull were never discussed with Heritage Victoria, and he never requested or received any indemnity from prosecution.

[24] Determination of the State Coroner, 0926/08 made on 1 September 2010.

[25] The investigations of the mass grave (Pit C) were undertaken by Heritage Victoria archaeologists Jeremy Smith, Brandi Bugh, Anne-Louise Muir, Rhonda Steel and Hanna Steyne with assistance from Catherine Tucker and Richard Marshall (Terra Culture). Background historical research was undertaken for Heritage Victoria by Helen Harris OAM and Carlotta Kellaway.

[26] Determination of the State Coroner, 3080/10 made on 2 September 2010.

[27] Sunday Herald Sun, 24 October 2010, p. 42. These were the only government funds that were allocated to this project. All other research, fieldwork and analysis were carried out as part of the core operations of Heritage Victoria, the coroner’s office and VIFM.