Last updated:

‘Local History from 8000 Miles Away: Early Colac Court Records in the United States of America’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 10, 2011. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Mitchell Fraas.

This article examines a volume of Colac court records from the mid-nineteenth century now held in the United States. It details the contents of the volume with an eye towards the nature of local justice in early Victoria and the ways in which legal records can provide a window into the past. In addition, the article calls attention to the increasingly global nature of local history studies. In sharing the story of this trans-oceanic ‘discovery’ and its subsequent digitisation, it provides a possible model for future directions in archival research.

Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) has long served as the first stop for genealogists, local historians and others researching Victoria’s past. However, no history is purely local. The state’s history is closely intertwined with countless others, whether of Australia as a whole, the wider British world, or greater south-east Asia. Accordingly, it is no surprise that records relating to the history of Victoria and its inhabitants are spread out across the world. Yet, while one might expect to find important documents on the state’s history in archives and libraries in London, Sydney, Dublin or Edinburgh, they also exist in much more unlikely places. This article tells the story of one of these far-flung historical records and also shows how archives, libraries, historians and interested citizens are taking advantage of new technology to bring these documents and their stories home.

Unlike other Provenance authors, I have never been to PROV, nor have I set foot in Australia. For much of the past decade I have lived and worked as a historian in Durham, North Carolina in the southern part of the United States. My engagement with Victoria’s history and PROV began in the summer of 2010 during my time as an intern in the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library (RBMSCL) at Duke University in Durham. While working there one July morning I received an email from Dawn Peel, a historian of the Colac district and Victoria generally.[1] She wrote to enquire about an item she had stumbled across in Duke’s online catalogue. The catalogue entry for the item had piqued her curiosity as it mentioned Colac and seemed to be a book of court records from the period about which she had written extensively. What exactly was in this book and how had it come to be at Duke, she asked?

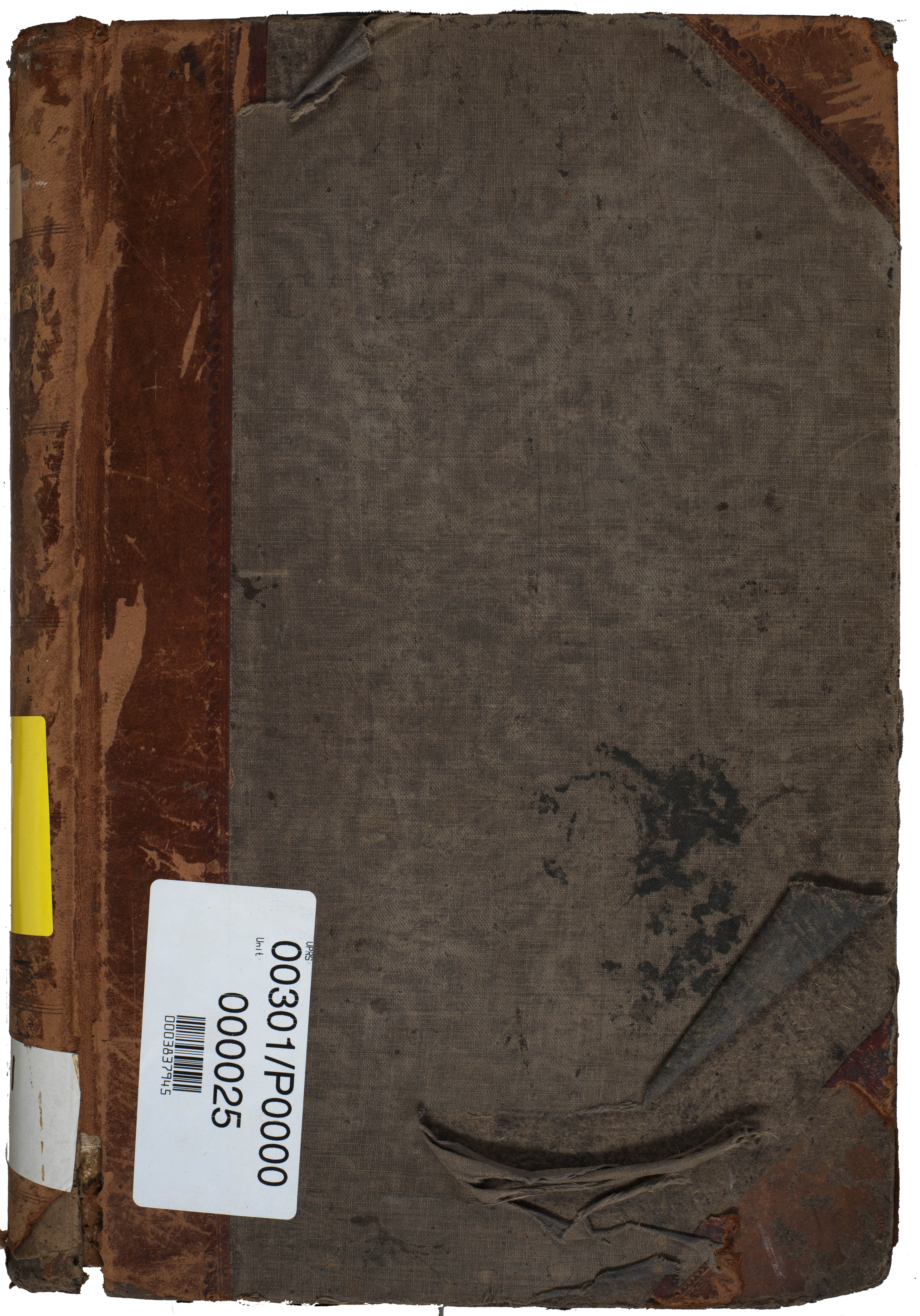

My academic specialty is the legal history of the British Empire, so I was immediately intrigued by her question and the mention of court records. I rushed into the stacks to retrieve the volume from a pile of various ledgers, American Civil War letterbooks, and other assorted bound manuscripts, brought it to the reading room and began to examine it. The document was in the form of a bound ledger with a leather spine and marbled boards, bearing the Duke shelfmark ‘F[olio]-759’. It measured 40 cm tall by 25 cm wide with the word ‘JOURNAL’ crudely cut into its spine. Though the volume contained 310 numbered pages, only pages 1-240 had been used for writing. Opening the cover I saw an old index card pasted into the volume labelling it as the original minutes of the Court of Petty Sessions at Colac from 1849 to 1865.

The Colac Court of Petty Sessions first opened in 1849 and, as such, the Duke volume contains the earliest legal records from Colac.[2] There is something intrinsically exciting to a historian about court records. Besides serving as a goldmine of genealogical information, court documents reveal the everyday lives of countless people otherwise ignored in the historical record. The Colac petty sessions records do not disappoint, providing a window on life in early Victoria. The Duke volume takes up the story of early Colac from the morning of 9 April 1849 when the court appears to have met in front of the public for the first time.[3]

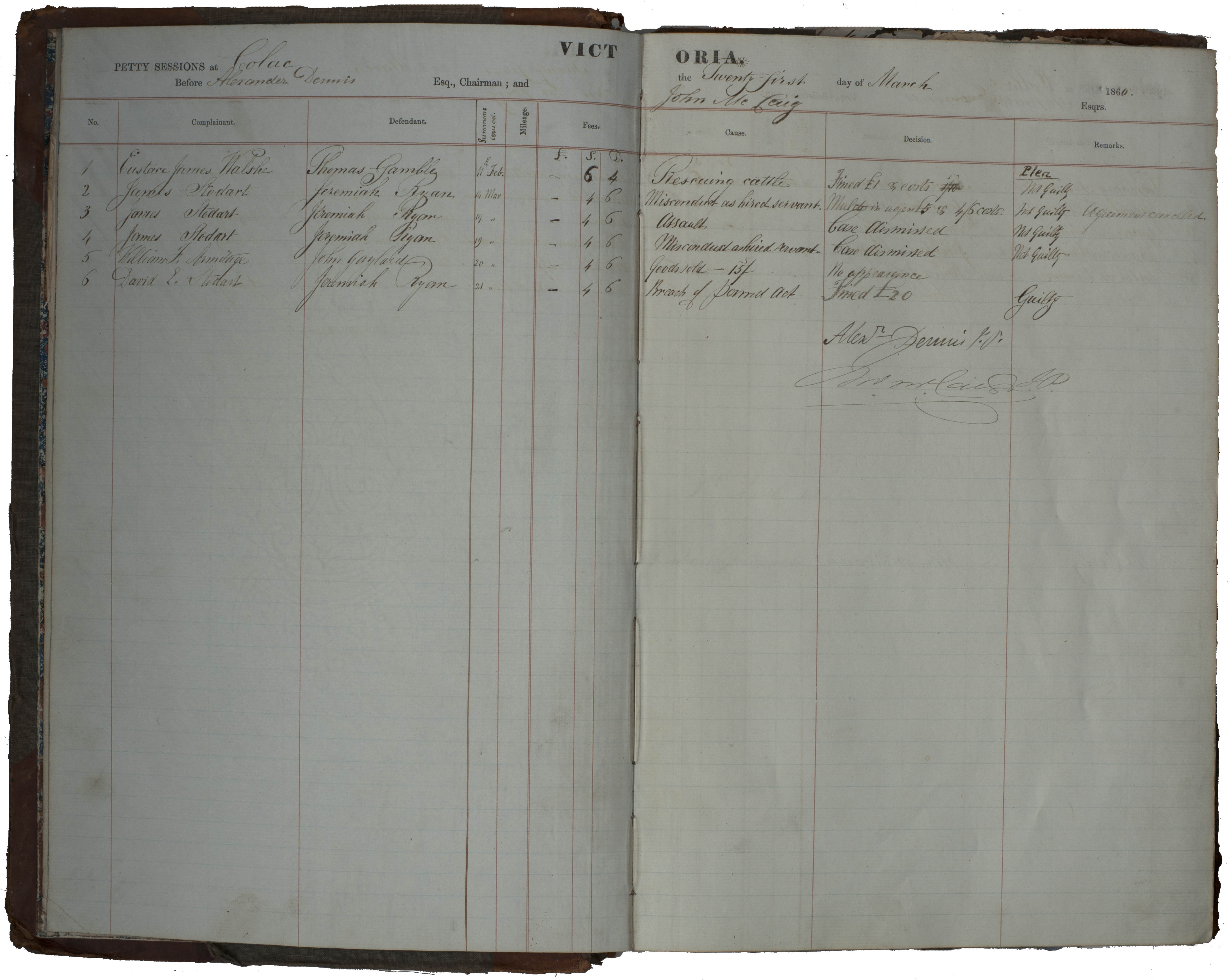

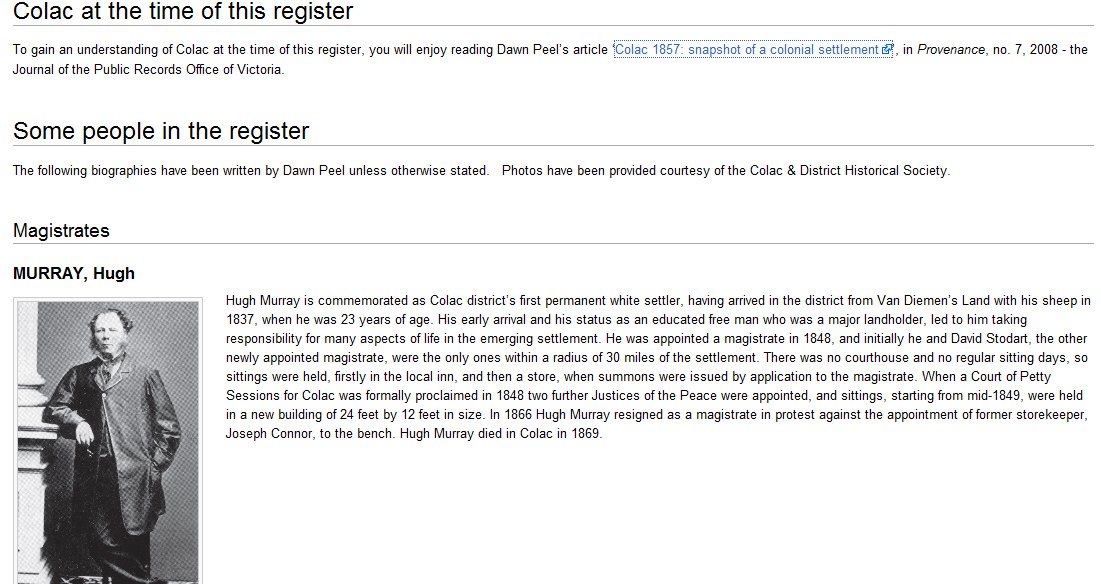

Like most local courts throughout the British Empire, the petty sessions at Colac depended on local notables and elites to oversee law and order and execute justice.[4] The court’s first magistrates included Hugh Murray, the founder of Colac, and other landowners who provided speedy resolution to the mundane problems encountered by the town’s mid-nineteenth-century residents. Judging from the minutes of the court, the magistrates appear to have called the sessions to order as frequently as twice a week or as infrequently as once a month - there are, for instance, no entries at all for July 1849.

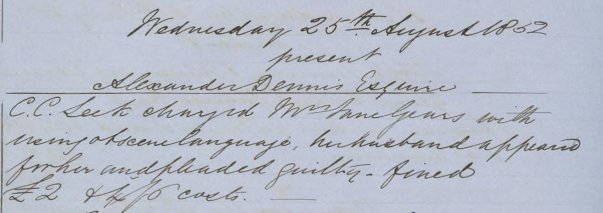

The Colac magistrates spent most of their time meting out punishment for petty crimes and settling small financial disputes between residents. Most of the criminal offences mentioned in the minutes are of a decidedly more minor nature, as in April 1850, when the aptly named William Fox was brought up on the charge of ‘stealing a duck’.[5] For these smaller criminal offences or other robberies the convicted could expect to be fined, sent to work on the roads, or transported to gaol in either Geelong or Melbourne.[6] Serious felonies like rape and murder are rarer in the court’s proceedings and it appears the magistrates usually sent those accused to Geelong or Melbourne for trial after an initial hearing as there were no regular jury trials at Colac.[7]

The minutes of the court are also full of cases relying on the infamous masters and servants Acts which provided strict penalties for labourers and servants who absconded or proved troublesome.[8] In 1849, for example, the court sentenced a sheep shearer to two months in the Melbourne gaol for absenteeism.[9] There are also numerous references in the minutes to the rather inebriated tendencies of many of the residents. In January 1850, for example, two scofflaws were brought before the court by a resident for ‘violently assaulting him and demanding spirits’.[10] In a similar vein, the court minutes detail ‘sly grog selling’, ‘walking onto the public road in a state of nakedness’, and the sad case of a man found dead, ‘presumed to have drowned while in a partial state of intoxication’, near an establishment called the Crook and Plaid. Early Colac watering holes such as the Crook and Plaid seem to have been a particular menace in the eyes of the magistrates and citizenry. For example, Colac businessman Michael Lyons registered his pub, The True Briton, with the court in 1849, only to appear at court countless times in subsequent years for various transgressions and assaults arising from his establishment.

The proceedings in the Duke volume are dominated by a small cadre of the first European settlers and contain only the faintest glimpses of non-European Australians living in the area. For example, in 1852 we find ‘Andrew Murray Esq.’, the younger brother of Hugh Murray, asking the court for a warrant to seize a Chinese washerman named Loopooh [sic] who had run away from his employer.[11] More tragically, in November 1850 the court minutes show the chief constable of Colac accusing ‘John and Jerry, two aboriginals’ of assaulting John Buckley, one of Hugh Murray’s servants.[12] When Buckley died as a result of this so-called ‘affray with the blacks’, the magistrates committed the two unfortunate accused for trial, the proceedings of which are not recorded in the Duke volume.[13]

The magistrates decided these cases based on what little legal knowledge they had, occasionally citing English statutes and those Australian law books they had on hand.[14] In other instances the judges looked to local custom. In 1857, for example, two residents brought a complaint over a stone wall to the court. The court eventually decided that not enough evidence about local custom existed to adjudicate the dispute and the plaintiff dropped his complaint. More often than not, the magistrates simply applied their own judgement of witnesses’ and defendants’ characters to render verdicts, a process common to local systems of justice throughout the British world.

Never having heard of Colac prior to her email, I knew Dawn would probably find even more of interest in the volume than I had and I immediately sent her reproductions of a few representative pages from the text. She replied enthusiastically that many of the names in the volume were familiar to her and asked with some incredulity how such a document could have ended up in North Carolina. Indeed, it appears that all other records of the Colac court of petty sessions are located at PROV in VPRS 301. The answer most probably lies in the nature of local justice and authority in nineteenth-century Australia. There was no regularised system of government archives at the time and perhaps one of the magistrates or clerks of the court simply kept the volume amongst his own possessions. The descendants of that official may then have sold or given away the document and it ended up in the inventory of the antiquarian book dealer Berkelouw in Sydney around 1961. The Duke University library bought the volume that year to add to its extensive holdings of British Imperial history and no notice seems to have been taken of it until Dawn’s email in 2010.

After Dawn and I established that the Colac volume was of significant local historical interest, we contacted the staff at PROV as well as Tim Pyatt, the then interim director of RBMSCL at Duke. In earlier decades, all parties would have had to work out some way for Australian researchers to use the volume, either by encouraging travel to Durham or through some sort of physical reproduction, either on paper or microfilm. Now, given the technological resources at our disposal, the staff at RBMSCL decided to make the volume available in a digitised format to allow the broadest possible access to its content. Fortunately, over the spring of 2010 the Digital Production Center of Duke University Libraries had begun to work with the Internet Archive to digitise some of the library’s collections. It seemed natural then to use this free and universally available web platform to display a digital copy of the Colac records. Over the next few months the digital productions staff took up the project with gusto and were able to deliver the entire manuscript in digitised form suitable for the Internet Archive. The volume is now available in its entirety through Duke University’s digital collections.[15]

However, the work of making this valuable historical record more accessible has not stopped with the digitisation on Duke’s part. In the weeks after Duke put the document online, Dawn reached out to a team of dedicated researchers and genealogical specialists to inform them of the find. Under the leadership of Susie Zada, these volunteers from various societies and family history groups managed to create a complete index to all proper names in the volume as well as a 351-page searchable PDF containing a transcription of the text.[16] Susie and her team also created a PROV Wiki guide to the digitised volume complete with brief biographies, background information and links to relevant PROV resources, all within the space of a few months.[17]

Now when historians of Colac, colonial law, or Victoria generally utilise PROV archives they have access not only to manuscript records held locally but to a complete searchable version of Colac’s earliest court from the other side of the world, virtually home again after a long absence. One can only hope that this kind of collaborative project, using the expertise and resources of institutions, scholars and citizens on two continents, will become increasingly common in coming years - facilitating ‘local’ history from anywhere in the world.[18]

Endnotes

[1] See her excellent work on Colac’s nineteenth-century history in D Peel, Year of hope: 1857 in the Colac district, Dawn Peel, Colac, 2006, and D Peel, ‘Colac 1857: snapshot of a colonial settlement’, Provenance, no. 7, 2008, available at: <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2008/colac-1857>, accessed 26 March 2020.

[2] As the area around Colac attracted more and more immigrants, the Colonial Secretary in Sydney officially established a court there for resolving local criminal and civil disputes as of New Year’s Day 1849. See The Argus, 12 January 1849, p. 1 for this announcement. For the best account of early Colac see Peel’s Year of hope.

[3] The volume begins with a page listing the appointments of various court officers, starting with the clerk of the petty sessions appointed on 1 January 1849. The minutes of the court itself begin on page 3. Beginning in 1860 (page 189) the nature of the volume changes: it ceases to be a minute book and instead consists of transcribed depositions, licenses, and brief references to court sittings. The complete digitised volume can be viewed here.

[4] For a fascinating comparative example see L Edwards, The people and their peace, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2009, which examines local justice in the nineteenth-century American south.

[5] See p. 24 in F-759, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University. All subsequent references are to this volume unless otherwise noted.

[6] For two men convicted of robbery being sentenced to labour on the roads see pp. 148-9 (25 March 1857). There are many instances of prisoners being sent to the Geelong or Melbourne prisons: see for example pp. 11, 40, 58.

[7] See p. 27 (24 April 1850) and p. 29 (17 May 1850) for just two examples of prisoners remanded to Melbourne for trial.

[8] As part of New South Wales until 1851, the Colac court depended initially on that colony’s statute of 9 George IV no. 9 (1828) and later on Victorian statutes such as 16 Victoria no. 2 (1852), 18 Victoria no. 16 (1855), and 27 Victoria no. 198 (1864). For the best scholarly treatment of these laws see M Quinlan, ‘Australia 1788-1902, a working man’s paradise?’, in D Hay and P Craven (eds), Masters, servants, and magistrates in Britain & the Empire, 1562-1955, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2004, pp. 219-50.

[9] Case of Mr Mogg as superintendent for Mr Harding against the shearer Frederick Castles, pp. 10-11 (9 October 1849).

[10] James Marr and William Brightwell pled guilty to this offence. See p. 17 (2 January 1850).

[11] See the case of Loopooh, p. 72 (2 June 1852).

[12] See pp. 42-3 (27 November, 2 and 3 December 1850).

[13] For an examination of conflicts between indigenous Australians and European settlers in the area as well as the role of the courts, see S Davies, ‘Aborigines, murder and the criminal law in early Port Phillip, 1841-1851’, Historical studies, vol. 22, 1987, pp. 313-35.

[14] See p. 17 where the magistrates cite the English statute 9 William IV c. 14 (1833) as well as Thomas Callaghan’s collection of statutes and laws applicable to Australia: T Callaghan, Acts and Ordinances of the Governor and Council of New South Wales, 1824-1844, and Acts of Parliament enacted for and applied to the Colony, 2 vols, Sydney, William John Row, Government printer, 1844-46.

[15] See <http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/books_Victoria.CourtOfPettySessionsRecords1849-1865/>.

[16] The index to the register has been added to the Geelong and District Database, while the full text transcription is available on the PROV website. This work was done by Joan Davis and Di Russell from the Winchelsea Historical Society, Pam Jennings and Susie Zada from the Bellarine Historical Society & Geelong Family History Group, and Dorothy Moore from the Bellbrae Family History Group. This monumental effort earned the Colac and District Historical Society a 2011 Sir Rupert Hamer Records Management Award.

[17] PROV Wiki, Colac Court records: on the other side of the world.

[18] This project would not have been possible without Dawn Peel, Tim Pyatt, Naomi Nelson, Mike Adamo, Seth Shaw, Noah Huffman, Josh Larkin-Rowley, Elizabeth Dunn, Susie Zada, Jill Vermillion, and many others.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples