Last updated:

‘Victoria Police Involvement in the Infant Life Protection Act 1893-1908’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 9, 2010. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Helen Harris.

This paper looks at the involvement of Victoria Police, from 1893 to 1908, in registering and supervising women who came under the control of the Infant Life Protection Act of 1890. The Act was established to regulate ‘baby farming’, a system in which single mothers would pay other women to look after their infants, while they themselves went back to work to earn enough income for both to live on. It points the researcher to a collection of relatively unknown and previously untapped sources, which provide intimate detail of the lives of working-class women who became ‘nurses’ and of the mothers who used their services.

Legislation enacted in nineteenth-century Victoria, in attempts to both assist and monitor the destitute, reflect the local situation of a colony of immigrants. In the United Kingdom destitute people were assisted to return to the parish of their birth, where local officials would provide shelter and food, more often than not in the shape of admittance to a workhouse.[1] This practice did not exist in Victoria, and so a variety of actions were taken by the colonial government, particularly with reference to destitute children. A good description of the various Acts passed in this regard can be found in Neglected and criminal: foundations of child welfare legislation in Victoria,[2] while Single mothers and their children: disposal, punishment and survival in Australia[3] is the most comprehensive work on the subject. This paper is an attempt to bring to the notice of researchers a vast collection of relatively unknown material that can be used to learn more about the lives of working-class women and their children, and, incidentally, the attitudes of law enforcers of the day.

The Public Health Amendment Act of 1883[4] was the first attempt by the Victorian government to regulate ‘baby farming’, the system where mothers of (mainly illegitimate) infants and small children paid other women a small weekly fee to house and feed their children in the carer’s home. While the Act itself came into operation on 5 November 1883, Part 3, relating to Infant Life Protection, was not to come into effect until six months later, presumably to allow for the preliminary documentation to be organised. Under the Act, a woman who wished to look after children under the age of two years had to apply to register her house with the local Board of Health, and, if successful, keep a register or roll book of the details of the infants under her control. The local Board had also to keep a record containing the names of those applying to register a house, and a description of the premises. The Board had the power to refuse to register a house if they were not satisfied that it was suitable for the care of infants, and to strike out the registration if they were subsequently unsatisfied with the manner in which the care of the infant/s was conducted. There was no mention in the Act of a requirement for regular inspections of either the houses or the infants in them.

The death of any child in a registered house had to be notified to the nearest coroner within twenty-four hours, and an inquest was mandatory, unless a medical certificate certifying the cause of death could be produced. Burial of a child was illegal without the necessary coroner’s or justice’s certificate.

Failure to comply with the provisions of the Act meant a penalty of up to six months’ gaol or £5. Interestingly, although the baby farmers or ‘nurses’ were overwhelmingly women, the Act used the male pronoun ‘he’ to describe them.

In July 1890 a further Health Act was passed.[5] The only change brought by this Act, with regard to the Infant Life Protection section (Part 7), was that henceforth local councils would be responsible for the registration and supervision of the system (this was an early attempt at cost shifting with which present-day local governments are all too familiar). Later that year a separate Infant Life Protection Act was passed by parliament, coming into effect on 31 January 1891, and superseding the earlier legislations.[6] In the new Act several conditions were tightened, financial penalties were increased to a maximum of £25, and the Chief Commissioner of Police was given the overall responsibility for registration and supervision of the scheme.

As always, however, the devil was in the detail, and as the Argus newspaper pointed out in November 1892, the Act was ‘practically a dead letter’ because no regulations prescribing how the Act was to be implemented had ever been passed by government.[7] While the editor was pleased that the authorities said they were at last preparing the required regulations, he pointed to recent events in Sydney, where a baby farmer had been implicated in the deaths of a number of children, as a cause for urgent action in Victoria. Two months later he asked pointedly, ‘How much longer is the public to wait?’[8] The answer was shortly forthcoming, with the regulations being gazetted on 9 January 1893.[9] Under these regulations, registers of premises used by nurses were to be kept at major police stations: Russell Street in Melbourne, and in thirty country towns.[10]

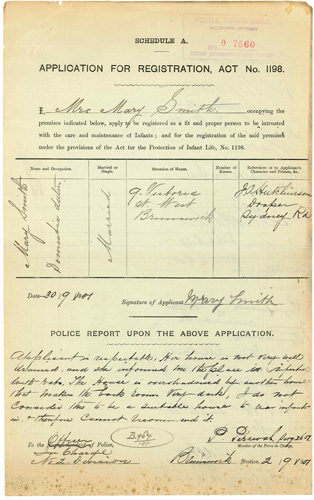

The number of infants who could be taken in by a nurse depended on the available floor space of a house, fifty square feet being the minimum requirement. Any house could be inspected ‘from time to time as occasion may require’. A special form was to be completed by the nurses when applying for registration. It recorded the name, marital status, occupation and address of the applicant, and included a column in which to list the people supplying references. Details of any child in the applicant’s care were to be listed, including its name and age, as well as the name of the person from whom she had received the child, and whether it was nursed (that is, wet-nursed), maintained or adopted.

The police department was to supply a roll book to each person registered under the Act, in which the names of all the children who were taken in was recorded, as well as the date of their departure and the manner in which they left. The book was to be returned to the department when the nurse retired. Each nurse had to renew her registration yearly, every December.

On 6 September 1893, police arrested Frances Knorr, née Thwaites, a Victorian baby farmer, and charged her with the murders of three infants whose bodies were found buried in the backyards of houses she had occupied in Brunswick. Knorr was subsequently tried, found guilty and hanged.[11]

Although Frances Knorr was not registered as a nurse under the Act, police command decided that the house and children of every registered nurse in the state should be inspected immediately, and a memo to this effect was issued to all police districts.[12] Each police district contained a number of police stations, and each station was instructed to provide the details of homes and children. Some police simply reported the number of registered nurses and the children they had: for example, Geelong had four nurses; Hamilton had two nurses with eight illegitimate children, but only named one of them. The North-East District and Benalla, Daylesford, Echuca, Port Fairy and Warrnambool stations reported that there were no registered nurses there. Other police went into great detail about the nurses, their homes, and the children boarding with them. The records thus produced are the only known surviving listing of registered nurses and the children in their care in this early period of the Act (all names have been extracted and reproduced on a webpage – see below).

Some institutions were exempt from the Act, and could give infants to nurses who were not obliged to register. These institutions – the Victorian Infant Asylum in East Melbourne; the Salvation Army Maternity Home in North Fitzroy (The Haven); the Lying-In Hospital in Madeline Street, Carlton; and the Female (Carlton) Refuge in Keppel Street, Carlton – were also visited, and reports compiled. The officer who did the inspections reported that the Infant Asylum and Salvation Army children were returned every month for inspection, while those who lived some distance away were regularly visited by committee and other members. In the case of the Female Refuge, however, the situation was different:

the infants were kept with the mothers for some time, but between 4-12 months, if a situation cannot be obtained for the mother where she can have her child with her, the child is boarded out to a suitable person selected by the Matron, but the authorities at the Female Refuge have nothing to do with the child from the time it leaves the institution.[13]

Clearly the situation at the Refuge was not satisfactory, and after police met with the Matron, Mrs Thompson, and the Ladies Committee, it was agreed that all infants boarded out would have to be returned for inspection once a month, unless they were with country nurses. In those cases ‘some competent person’ connected with the Refuge would visit them in their homes.

Creches, in Richmond run by Miss Gilly Turton and in Collingwood run by Miss Clara Langley, were also inspected, but as the children were not kept overnight, the Act was not relevant to their situation.

In December 1893, the following institutions were also exempted from the Act: the Benevolent Asylum and Female Refuge at Ballarat; the Bendigo Benevolent Asylum; and in Geelong, the Convent of Mercy Female Orphanage, St Augustine’s Male Orphanage, the Geelong Protestant Orphanage, the Female Refuge and the Salvation Army Home.[14]

To assist with the inspections, Chief Commissioner HM Chomley selected a number of female volunteers who were to inspect the nurses’ homes regularly. This plan did not work in practice, however, as middle-class women would not visit working-class areas, and most volunteers were of the former class while most nurses were of the latter.

In January 1898 the Chief Commissioner provided a summary of the administration of the Act. He felt that it needed an amendment

so as to prevent a nurse adopting a child for a lump sum. So long as she received a small weekly allowance for its care it was to her interest to keep the child alive, but, having received a lump sum, there was no longer the same incentive.[15]

There are newspaper reports of an amendment to the Act being discussed in parliament late in 1899, but it does not appear in the list of Victorian Acts.[16] Certainly the provision regarding lump sum payment was changed, as numerous files make clear.

In 1898 Victoria Police took over the entire administration of the Act, added extra requirements, and in the process generated a huge volume of paperwork. Police made detailed and minute notes of the cases they investigated. The background of each applicant for registration as a nurse, the number of people living in her home, and its physical dimensions were all recorded. Nurses were now also subjected to fortnightly visits by a local constable (in plain clothes), who inspected both her home and the infants within it. The responsible constable had also to compile a monthly return of every nurse in his district, listing their names and addresses, the children they had with them, the next of kin of the children, and the condition of the children’s bedding and feeding bottles. These monthly returns were submitted to headquarters, and are to be found today within police correspondence records.[17]

While most of the nurses were from the inner suburbs of Melbourne, the children they cared for came from a wide variety of places. For example, in 1898 Ella Harding of Brunswick had Ellen Jeffers, whose mother was in Mooroopna,[18] while in 1901 Harriet Lawson of Collingwood had Grace Tracy McAlpine, whose mother was in Myrtleford, and Mrs E Cameron of Richmond had Edward Braybrook, whose mother was in Loch, Gippsland.[19]

The Act had an impact not only on the lives of nurses and children, but also on statutory processes such as the registration of births. Ordinarily, a child had to be registered within six weeks of birth. Under the Infant Life Protection Act, however, an illegitimate child’s birth was required to be registered within three days.[20] Given that the mother might not be well enough to do so, the requirement fell on the occupier of the house in which the child was born.

Failure to comply with these requirements meant that the local Registrar informed police. An investigation of the circumstances took place, with a view to prosecution in the local Court of Petty Sessions. The mother was interviewed, and also the person in whose home the child had been born, as it was the latter who would be charged. Details of the paternity of the child are often given in these cases. Although a breach of the Act had occurred, the Chief Commissioner used his discretion when there were extenuating circumstances, and some cases were never proceeded with, as the following case shows.

Ileen May Davey was born in Footscray in 1903. When her mother, Caroline Annie Maddox (née Hall) went to register the birth, she found she was in breach of the Act, as it was more than three days since the birth. The father of the child, Reg Davey, a baker, of Hopkins Street, Footscray, was interviewed, and claimed ignorance of the requirements of the Act. A prosecution brief was prepared, but Caroline Maddox visited the local station and pleaded her case with Constable Charles Dwyer, who duly reported:

She appears to be a respectable person in a small business in Footscray. She has 3 other girls, born in wedlock, the eldest is 14 years. I think this is a case in which a summons should not issue, as Mrs. Maddox is a hard-working industrious woman and has been shamefully treated and deserted by her husband six years ago.

Exposure of her private life could have been ruinous for Caroline’s business, as the Chief Commissioner was quick to realise, and the prosecution brief lapsed.[21]

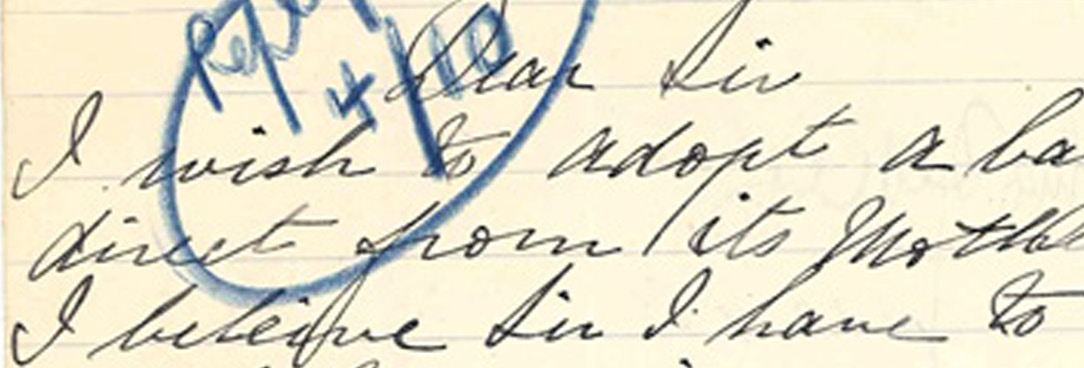

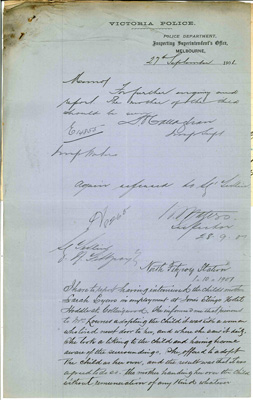

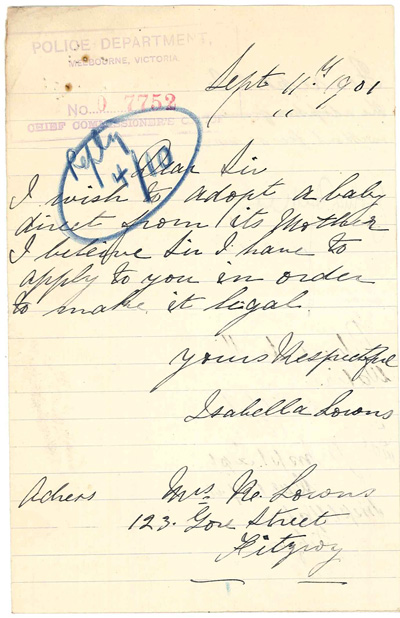

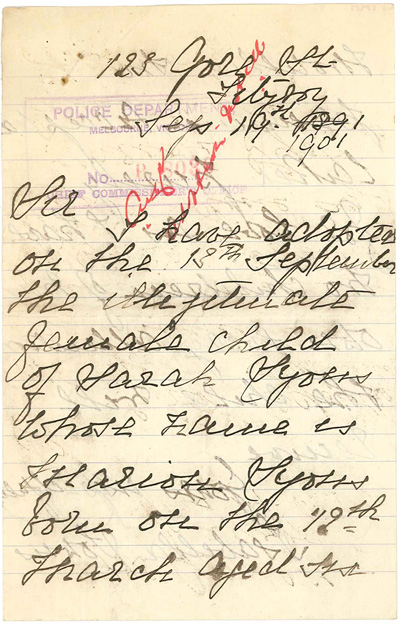

Many single women had neither the ability to care for the child themselves, nor the means to continue to pay a baby farmer, so had no objection to the child being adopted. The only requirement under the Act, regarding adoption, was for the adoptive parent to write to the Chief Commissioner of Police, seeking approval.[22] He would refer the letter to local police, who would then compile a report on the applicant. Upon confirmation of the bona fides of the adoptive parents, permission would be given, via a letter, and a note made on the file. Occasionally a solicitor also drew up a formal statement signed by both parties, and a copy was given to the department.

An example of the type of information that can appear with adoption papers is that of Sarah Lyons, who gave birth to an illegitimate child in Richmond in 1901. Sarah was a widow, her husband having died fifteen years previously. She had been deserted by the father of the child in Adelaide, and had a blind son to maintain there. Like a number of women she travelled interstate to give birth, and thus avoid a scandal (some women came from as far away as New Zealand). Sarah left the child with a nurse in Melbourne, and in the same year Isabella Lownes successfully applied to police to adopt it.[23]

Not all the adoptions were of illegitimate children; some mothers were simply destitute and had a number of other children to support. In at least one case there is reason to suspect a society cover-up occurred in the process of adoption.

In November 1901 the Chief Commissioner received a letter from Dr David Egryn Jones of Collins Street, the husband of Dr Constance Stone:

Sir,

a boy named John Francis Barkle is now boarded out with Mrs. Nichol at 1 Downshire Rd. Elsternwick under police supervision. An opportunity occurs to get him adopted, without any money consideration whatever, by people who will thoroughly look after him and the adoption will be very greatly to the boy’s advantage. There are circumstances which make it desirable that the police should not interfere with him in his new home, if that is at all possible. I am willing to give a personal guarantee that the child will be well treated, and if necessary to bring him before you, if at any time enquiry should be considered necessary.

I would beg that the police at Elsternwick should be informed that it is not desirable to give any information in regard to parentage to anyone. Should this rather vague arrangement not be satisfactory to you I shall be pleased at any time to call at your office and make full verbal statements. Trusting my request may receive your favourable attention …

Chief Commissioner Chomley did ask for more detail, and on the back of the letter noted:

Dr. Jones has explained all the circumstances to me and I should be glad if the police complied with the request of Dr. Jones, not to give information about the parentage of this child to anyone.

The file went to Elsternwick police station, on 9 November, where the request was duly noted by the officer in charge, who replied that the directions would be

strictly observed at this Stn. I have also requested Mrs. Nicol to refrain from giving any information concerning the child.

The arrangements did not find favour with the nurse, however, and a letter from her to the Chief Commissioner arrived on the same day:

Sir,

I have this day given up charge of Jack Franklin Barkle, aged two years & seven months old, to a strange man whose name I do not know, & he has gone where I have no idea. I was written to by Dr. Constance Stone who told me to take the little boy into her rooms in Collins St., & this strange man would be there. When I asked him to sign the book, he refused, saying Dr. Stone had told him Dr. Jones had been to Mr. Chomley & there was no need to tell any name or where he was going. I made him repeat this statement before Dr. Clara Stone, who told me she was sure it was all right, tho I strongly objected to the whole thing. I hope I have not done wrong; but to my mind it is a strange thing that influence can let off one person & a poor servant girl has to tell all her business, or she is religiously hunted up. I have cared for this child since he was a fortnight old, & loved him as a mother & today I saw him carried off screaming down the street, it was cruel. No one has ever been to see him, save once, this man called last December, it is a cruel thing to take him at this age, amongst strangers. You will remember it was this case that Dr. Stone refused to give the mother’s name to me, and it had to be seen to afterwards. Trusting you will see he is well cared for, I remain yours sincerely,

Margaret S. Nicol.

The file reveals that the child went to the principal of the Daylesford primary school, but nowhere is the parentage mentioned.[24]

By 1906 over 500 nurses were registered,[25] and the police department was being overwhelmed by the amount of time and paperwork that was involved in regulating the Act. As well as checking the new applications to register, each nurse’s home had to be inspected fortnightly, and monthly returns compiled. Children who had left a nurse’s care had to be followed up, adoption applications had to be checked, and breaches of the Act prosecuted. Constables complained that they could not undertake other work because they were devoting so much time to fulfilling the requirements of the Act.

The surviving indexes to correspondence back up the constables’ claims.[26] They show that twenty pages per year, of one-line entries, were devoted just to the Infant Life Protection Act requirements. In November 1907 the Act was amended, and the Department of Neglected

Children was given the responsibility for its regulation.[27] In February 1908 the first paid Female Inspector, Marie Madeline Maxwell Murray was appointed, at a salary of £120 per annum.[28]

As the above examples show, the correspondence files contain a wealth of fascinating material. Locating this material is problematic, however. There is no index to police correspondence prior to 1901. After that date, where there is an index entry and a file number, trying to locate the file within VPRS 807 (Inwards Correspondence to the Chief Commissioner, 1894 onwards) is a hit-and-miss exercise, with about a 50% success rate. Many files are simply not where they should be; Criminal Offence Reports, which used the same numbering system, have been mixed up with correspondence files; and some files have been placed in Units which have no relationship to either the file number or the year of the event. As well, there are around 200 Units of miscellaneous correspondence which have never been catalogued, any one of which can contain material from a wide range of years, from 1853 to 1940. Some years ago I listed the names of all people referred to in the indexes from 1901-1908 and released a series of microfiche indexes, along with a listing of the Units in which they should (but not necessarily would) be found. A copy of the microfiche is held in the PROV reading room at North Melbourne. Since then I have listed many names and basic details found about them on my website: see Infant Life Protection Act Indexes.[29]

This article has focused on just one of a number of different bodies of information that can be found in police correspondence files, mainly those within VPRS 807. Given the paucity of records showing the intimate and private lives of working-class women, both married and single, and their surroundings, these files are a treasure trove of primary source material. They can provide the researcher, whether family historian or academic, with the opportunity to solve long-standing questions about paternity, adoptions, and family and work arrangements. Sometimes the answers are written in the women’s own hand, and sometimes the women are quoted verbatim.

Endnotes

[1] Except for widows and married women, who were sent to their husband’s birthplace. See ‘The Workhouse’, available at <http://www.workhouses.org.uk/>, accessed 22 October 2010, for details of the British scheme.

[2] D Jaggs, Neglected and criminal: foundations of child welfare legislation in Victoria, Phillip Institute, Bundoora, Vic., 1986.

[3] S Swain & R Howe, Single mothers and their children: disposal, punishment and survival in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Oakleigh, Vic., 1995.

[4] An Act to Amend the Laws relating to Public Health, No. 782. All Acts mentioned here can be accessed online via the Victorian Historical Acts database, available at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[5] Health Act 1890. An Act to Consolidate the Law relating to Public Health, No. 1098.

[6] Infant Life Protection Act 1890, No. 1198.

[7] Argus, 23 November 1892, p. 5a.

[8] Argus, 4 January 1893, p. 4h.

[9] The regulations appeared in both the Victoria Government gazette, 13 January 1893, p. 145 and the Victoria Police gazette, 18 January 1893, pp. 19-20.

[10] These were: Ararat, Bairnsdale, Ballarat, Beechworth, Benalla, Bendigo, Castlemaine, Daylesford, Echuca, Geelong, Hamilton, Horsham, Jamieson, Kilmore, Kyneton, Mansfield, Maryborough, Mildura, Nhill, Omeo, Palmerston, Port Fairy, Portland, Sale, Shepparton, St Arnaud, Stawell, Wangaratta, Warragul and Warrnambool.

[11] M Cannon, The woman as murderer, Today’s Australia Publishing Co., Mornington, Vic., 1994.

[12] PROV, VA Victoria Police, VPRS 937 Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 348, Bundle 1.

[13] ibid.

[14] Victoria Police gazette, 13 December 1893, p. 334.

[15] Argus, 15 January 1898, p. 11f.

[16] Argus, 25 September 1899, p. 4; 9 October 1899, p. 4.

[17] PROV, VA 724 Victoria Police, VPRS 807 Inwards Correspondence to the Chief Commissioner.

[18] ibid., Unit 1274, No. 3155.

[19] ibid., Unit 164, No. 9388.

[20] Infant Life Protection Act 1890, Section 18.

[21] PROV, VPRS 807, Unit 1226, No. 6046.

[22] Section 22 of the Act.

[23] PROV, VPRS 807, Unit 160, No. 7752.

[24] ibid., Unit 164, No. 9435.

[25] ibid., Unit 323.

[26] PROV, VA 724 Victoria Police, VPRS 10257. The Index to Correspondence is in a subject-based format.

[27] An Act to Amend the Infant Life Protection Act, No. 2102.

[28] Victoria Government gazette, 12 January 1908, p. 971.

[29] Helen Doxford Harris, ‘Infant Life Protection Act’, available at <http://helendoxfordharris.com.au/historical-indexes/ilpa>, accessed 22 October 2010.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples