Last updated:

‘The Turbulent History of Our Cookery Book’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 9, 2010. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Alison Wishart.

This is a peer reviewed article.

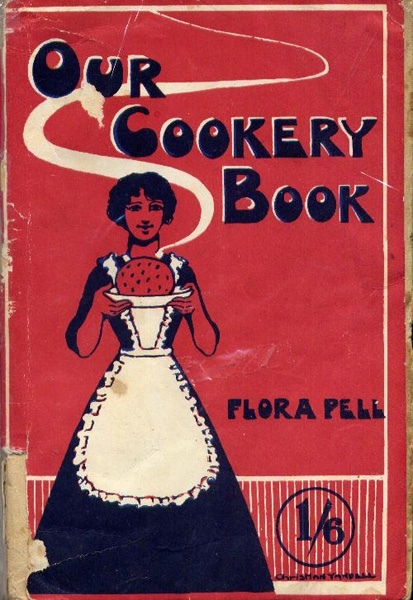

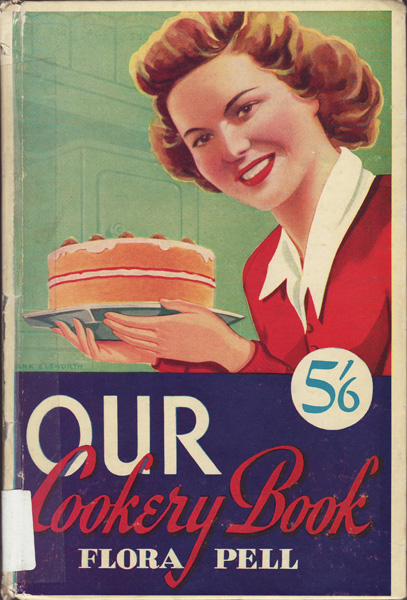

In 1916, Melbourne’s George Robertson published Our cookery book by Flora Pell. It was so popular that it remained in print until the 1950s and went into at least twenty-four editions. However its author, a long-serving employee of the Victorian Education Department, became a victim of departmental officiousness and was reprimanded and punished for showing initiative and skill. Our cookery book was also censured by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) as it contained recipes with alcohol, even though its author shared the same social and moral goals as the WCTU. The vexed history of Our cookery book, which brought to an end the thirty-five-year teaching career of Miss Pell, is documented in the correspondence, memos and departmental marginalia of a Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) file that is deceptively named ‘Red Cross Special case’.

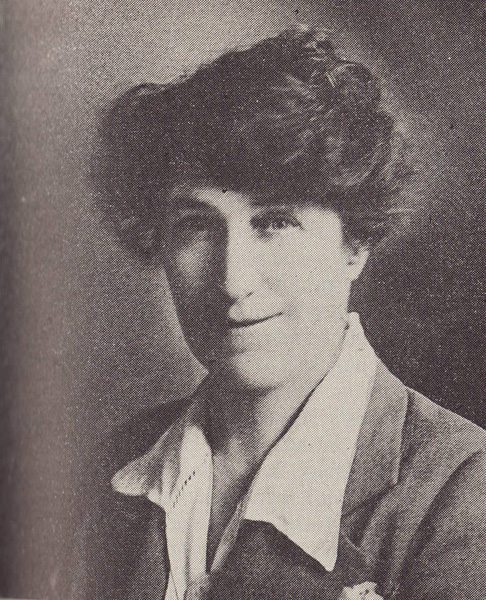

Miss Flora Pell, Teacher and Author

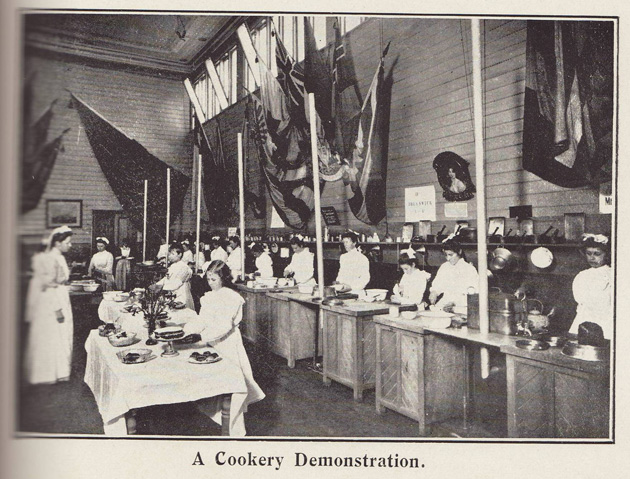

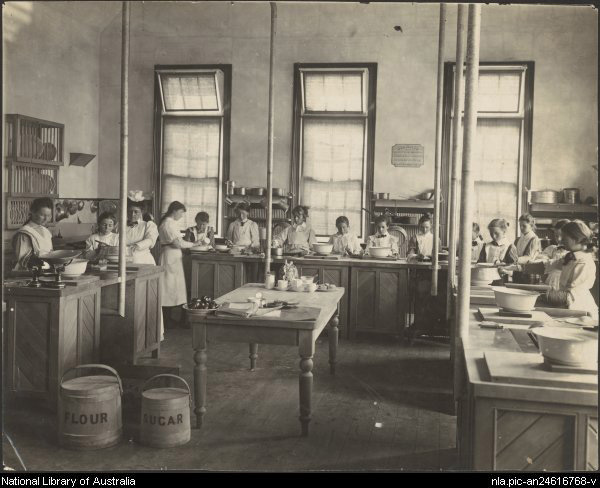

Flora Pell was born in Melbourne on 12 March 1874 and commenced work as a probationary teacher when she was only fifteen years old. She passed her teacher’s exams and became an Instructor in Cookery at schools in Geelong, Bendigo and then Carlton. This prepared her to organise the cookery section at the State Schools Exhibition in 1906.[1]

From CR Long (ed.), Record and review of the State Schools Exhibition … 1906, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1908, facing p. 68. Copy in National Library of Australia.

When Pell was appointed Supervisor of Cookery at the Melbourne Continuation School in 1908, her superiors stated that:

[Pell] has undertaken the training of the first cookery teachers. Exceedingly hard-working, capable, interested, reliable, enthusiastic, tactful. Miss Pell is a valuable public servant.[2]

From CR Long (ed.), Souvenir book: the aims and work of the Education Department, [Education Department], Melbourne, 1906, facing p. 24. Copy in National Library of Australia.

Pell continued to rise through the ranks of the Victorian Education Department, becoming headmistress of the Collingwood Domestic Arts School when it opened in 1915.

Photograph courtesy John Young.

While she was in charge of this school, Pell seized the opportunity of a meeting in Melbourne in June 1918 of all the State Education Department directors and organised for her cookery students to prepare and serve a four-course luncheon. The Victorian Premier, Minister for Education, Director of Education, and Mayor of Collingwood also tasted the students’ achievements and were most impressed.[3] Pell knew that good cooking could be persuasive and strategic.

Flora Pell’s career followed the expansion of systematic instruction in cookery – one of the technical subjects that broadened the emphasis of schooling beyond basic literacy. Judging by the annual reports Pell submitted to the Director of Education, it appears that she oversaw the development of cookery and sloyd centres (woodwork was called sloyd then) in state schools around Victoria from 1912. In 1914 she reported that there were forty-seven centres in full working order and that sixteen new centres had opened in that year.[4] These centres were usually attached to the local high school. In 1924, Pell was appointed Inspectress of Domestic Arts Centres throughout Victoria, a position she held until her retirement due to ‘ill-health’ in 1929 at the age of 55 years.[5]

The domestic arts movement was actually a transnational one, and however isolated Australia may have seemed in a geographical sense, the movement was not removed from developments elsewhere. The United States as well as England provided inspiration and models, and the interplay between external influences and local experiences is apparent in Pell’s own work. In 1923, she embarked on an ‘extensive tour of America’ to examine the domestic arts schools in that country. It is likely that Pell organised and funded the tour herself, as there is no information in the Education Department records to indicate otherwise. She concluded that while the equipment and facilities in American colleges were ‘magnificent’, schools in Melbourne had ‘nothing to learn’ from them. However, she did think that Australians would benefit from incorporating aspects of the American diet, which included salad with almost every meal, far less red meat, and ‘dainty’ breakfasts of ‘grapefruit or oranges and freshly made rolls and coffee’.[6] As she toured the United States, she gave lectures about cooking and Australia.

In 1916, Our cookery book was published by George Robertson in Melbourne. By this time Pell had been teaching cookery in Victorian schools for nearly twenty-five years. She felt there was a need for a cookery textbook to replace the recipe cards that the students (all girls) invariably lost and to provide more recipes and information. Our cookery book became the informal cookery textbook and at least twenty-four editions were published between 1916 and the 1950s. New editions of the book continued to appear even after her death in 1943.[7]

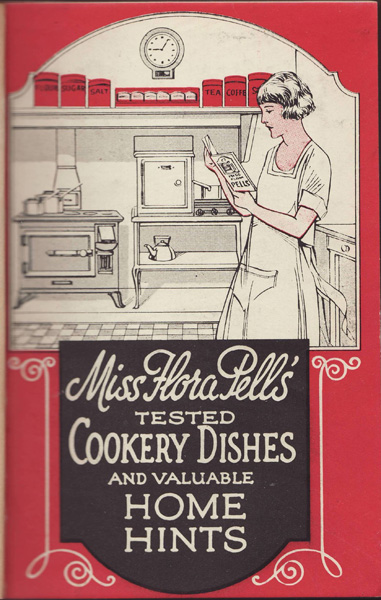

By 1925, Flora Pell’s reputation had grown to the extent that her publishers (now Specialty Press) thought it would be profitable to issue a book with her name in the title: Miss Flora Pell’s tested cookery dishes and valuable home hints.

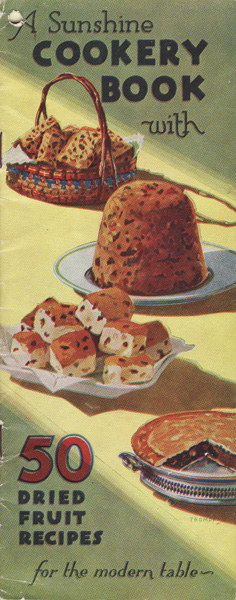

Pell’s reputation as a cookbook author continued to grow and led to the Victorian State Dried Fruits Board asking her in 1926 to compile a recipe book with fifty recipes containing only dried fruits. The result was A sunshine cookery book.

This cookbook was distributed free of charge to encourage Australians to eat more dried fruits. Australians were only consuming about one-third of the fruit grown in the country, much of which was cultivated by returned soldiers. These two publications created more demand for Pell and she soon found herself being invited to speak to women’s, business and charity groups.[8] From 1925 to 1928 she had a regular spot on Melbourne’s 3LO radio where she discussed cooking tips and domestic economy. Her ideas were often aired in the press, particularly by her friend Mrs Stella Allan who used the pseudonym ‘Vesta’ to write the weekly ‘Women to Women’ column in the Argus. Pell was on the airwaves, in print and in the papers. She may have been Australia’s first celebrity chef!

Copy in National Library of Australia.

Photograph by Alison Wishart.

Through royalties and her career, Pell gained financial independence, something only a minority of women of her age and era experienced. She did not marry until she was sixty years old in 1935. It is uncertain whether she chose a career over marriage, though given her attitudes towards the importance of motherhood and a woman’s duty to fulfil her ‘heaven-appointed’ mission to be a ‘wife and home-maker’, this seems unlikely.[9] Family circumstances meant that she was the bread-winner, as her father re-married following the death of her mother and had four more children before he died in 1893.[10] It is probable that as the only surviving child from her father’s first marriage, Pell was actively involved in caring and providing for her four step-siblings. Their mother, Charlotte (née Jeffreson) did not re-marry.[11]

Photograph by Alison Wishart.

Photograph by Alison Wishart.

The Turbulent History of Our Cookery Book

Our cookery book was a source of both great pride and distress for its author. It stands as a significant historical resource because its very purpose was to teach the general principles and techniques of contemporary cookery – the basic preparations for meals that were common at the time. It was used by mothers and daughters alike. However, by including a few recipes with alcohol in Our cookery book, Flora Pell raised the ire of the temperance movement and witnessed their lobbying strength. Its popularity as an unofficial textbook in school cookery centres and domestic arts colleges also exposed her to the full force of the Education Department’s wrath and power and led to her premature retirement in 1929.

The genesis of Our cookery book came from Pell’s extensive experience as a cookery teacher in Victorian schools. The Education Department required cookery students to purchase a set of 30 recipe cards for 1 shilling per set, with replacement cards costing 1 pence each.[12] Pell saw the need for a cookery book with more recipes and information about nutrition, cuts of meat, economising with food and leftovers, cooking for invalids and general cooking tips. She wrote her cookbook, found a publisher and wrote to the director of the Education Department on 20 December 1915 seeking his permission to bring out a book to replace the recipe cards.[13] When director Frank Tate replied that he did not want students to have to purchase a book, Pell was undeterred. Our cookery book was published, and at a retail price of 1s 6d was quickly taken up by cookery teachers and students.

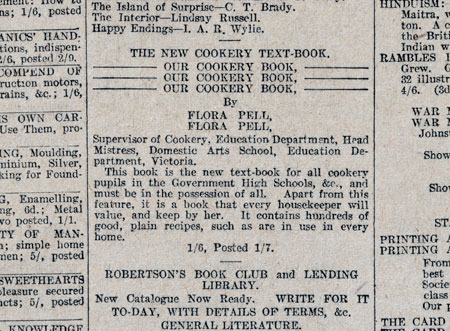

Image courtesy National Library of Australia.

Publicity for the cookbook in the newspapers proclaimed: ‘this book is the new text-book for all cookery pupils in the Government high schools and must be in the possession of all’.[14]

When the Education Department saw the press, Pell received a strongly worded letter from her employer demanding to know on whose authority she had issued a textbook. She replied that she had worked on the cookery book in her own time, did not authorise the use of the words ‘text-book’ in the advertising and then went on the offensive, quoting an independent reviewer who opined in the Argus: ‘it is doubtful whether any cookery book has yet been issued which would make the work as easy as this does for young housekeepers’.[15] The department wrote back to Miss Pell on 26 August 1916 stating that Our cookery book was not approved by the minister and could not be recognised as a textbook. This was intended to close the matter.[16]

Image courtesy National Library of Australia.

It is unclear whether Pell actively encouraged the use of her cookery book in schools or neglected to discourage it, but in any case Our cookery book gradually replaced the department’s recipe cards. Its use may have gone unnoticed by the department if not for the vigilance of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). In 1926, ten years after Our cookery book was first published, the Victorian branch of the WCTU wrote to the Director of Education, concerned that school children were being taught to make trifle using sherry. The director asked Pell if any such recipes were in use in schools and she replied that wine was not used in any recipes that were taught in cookery classes. Technically, this was true, as the recipes in Pell’s book which do contain alcohol, ‘namely rich fruit cakes and pudding with a little brandy which enables the sauce to be kept for a length of time … take five hours to cook without allowing time to prepare so can not well be included in a day’s cookery practice’.[17] However this was not good enough for the WCTU, who wrote to the director again on 21 May 1928 ‘respectfully requesting’ and ‘urging’ him to make good his ‘definite promise’ made at a conference held at Bell Street Domestic Arts College in November 1927 to remove the cookbook ‘which includes intoxicating liquor in recipes’.[18] Pell’s popular cookbook, which was not approved for use in schools, was causing embarrassment to her employer. When asked to explain, Pell realised that she could not stand up to the might of the WCTU and promised to make arrangements with her publisher to have all the offending recipes removed from subsequent editions.[19] This victory was announced in the newsletter of the Victorian branch of the WCTU.[20]

The WCTU started in the United States in the 1870s and spread to Australia in 1882. It attracted middle-class women of modest education from Protestant Christian backgrounds whose churches generally opposed alcohol.[21] The motto of its newsletter, The white ribbon signal,[22] was ‘For God, Home and Humanity’, which showed its strong Christian roots. While prohibition of alcohol was its main goal, over the course of its history the WCTU also campaigned for women’s suffrage, women’s right to stand for political office and to work as Justices of the Peace, Aboriginal land rights, and peace, and opposed the vices of gambling and tobacco.[23] It was closely aligned with the National Council of Women and the Housewives Association, which also supported the temperance movement, and members sometimes belonged to all three organisations.[24] The membership of the Victorian branch of the WCTU nearly trebled during the 1920s from 3,118 members in 1920 to 9,776 in 1930, making it the largest state branch.[25] Their political power was evident after they successfully campaigned for the closure of Victorian hotels and public bars at 6 pm in 1916 and helped to convince 47% of adult Victorians to vote for the reduction or abolition of liquor licenses in a referendum in 1920.[26] When they agitated from 1926 to 1928 for the removal of recipes containing alcohol from Pell’s cookery book, they had an expanding supporter base that politicians and bureaucrats would have been foolish to ignore.

Ironically, Flora Pell’s reports for the Education Department and the preface or introduction to her cookery books indicate that she subscribed to the ideals and principles of the WCTU and the Housewives Association. All three encouraged women to continue in their traditional domestic role and elevated the importance of the housewife. Pell realised that ‘the housekeeper is in a position to wield a tremendous influence on the mind and body, hence upon the family, society, and the nation’.[27] Values of thrift, efficiency, stewardship of resources (for example fuel, cloth, food), fidelity, hard work and fair dealing were promoted by the Housewives Association and by Flora Pell.[28] Pell argued that women and girls did not have an innate knowledge of the skills required for their ‘heaven-appointed’ mission to be a ‘wife and home-maker’ and that they needed to be trained in the ‘scientific and business principles needful for the organization of the modern household’.[29] This was becoming increasingly important as more girls moved out of domestic service and into factory work from the 1890s onwards.[30]

Both the WCTU and Pell were seeking to describe and empower women as ‘nation builders’. In 1897, Elizabeth Nicholls, speaking at a WCTU convention, said that the members of the WCTU who were ‘the representatives of the organised motherhood and sisterhood … are equally entitled to the name of “Nation Builders”’.[31] Pell also believed that nation-building started in the kitchen and wrote in 1906: ‘the teaching of domestic economy is to be the power that makes the happy home, and the happy home means a prosperous nation, because, from the home, we must recruit our citizens’.[32] Pell called on the government to protect ‘the integrity and dignity of home life … as a factor of national prosperity’.[33] This is precisely what the WCTU was seeking to do through the prohibition of alcohol.

Flora Pell, the WCTU and the Housewives Association were all proponents of ‘domestic feminism’ and upheld socially conservative gender roles. When Pell gave her farewell address at the Vere Street Domestic Arts Centre in June 1924 (she had been promoted to the position of Inspectress of Domestic Arts Centres in Victoria), she stated that girls were ‘the guardians of the future’. She believed there was a link between training girls to be wise mothers who ran efficient and effective households and who cared for the physical, mental and moral health of their children, and the prevention of juvenile crime.[34] Women might be allowed to work outside the home in a limited range of occupations but their most important work would take place in the home.

While Pell was espousing the moral steadfastness of a continuing education for girls in household economy and domestic science, community leaders in Melbourne and the WCTU were concerned about the return of soldiers from World War I with venereal diseases who drifted in and out of employment.[35] They feared that young girls, who finished school in their fourteenth year but were not allowed to start work in factories until they turned fifteen, and the returned soldiers would drift towards each other. Programs that trained girls in the principles and practices of motherhood were seen as one way of helping to control the spread of VD.[36] To prevent young girls from developing lazy, and possibly even immoral habits, Pell advocated that girls should be kept under the control of the Education Department and made to attend domestic arts centres for at least a couple of days a week.[37] However, as secondary education grew in the inter-war years, more girls chose to take up academic rather than domestic arts/science courses in senior years.[38] The WCTU was also concerned about the moral education of young girls and established the Frances Willard Club for girls and the daisy chain ‘recruit a friend’ campaign.[39] Pell and the WCTU thus shared the same moral values and Christian principles, but the latter was the more politically powerful and believed prohibition was the best way to achieve a society characterised by justice, peace and purity.

The popularity of Our cookery book, in schools as well as homes, was once a source of pride, pleasure and profit for Pell and her publisher. It now became a nightmare. It was the catalyst for the end of her forty-year teaching career. After the WCTU had alerted the Education Department to the continued use of Our cookery book in schools, the new director, Mr NP Hansen, questioned how the book came to supplant the recipe cards, and whether Pell had the right to receive royalties for a book that was published using her departmental title of ‘Supervisor of Cookery, Education Department and Headmistress, Domestic Arts School’ and later ‘Inspector of Schools’. The department was annoyed that 1,900 sets of its recipe cards were sitting unused and unsold at the Government Printing Office, while Pell and her publisher were reaping rewards. Pell was called before the director and the two top bureaucrats in the Education Department on Saturday 14 July 1928 and informed of the ‘undesirability of officers being interested financially in books of which they could officially influence the use, and advised to apply for permission to accept royalties’.[40]

The publisher, Specialty Press, feared that this profitable cookbook, which was in its 11th edition, could be banned and wrote to the department on 11 June 1928 requesting permission to continue to publish the book but with no recipes containing alcohol and no advertisements. They submitted a proof of the cookbook for approval in July. The department sent this copy to Miss RS Chisholm, headmistress of the Emily McPherson College of Domestic Economy, seeking her opinion on the suitability of Our cookery book as a school textbook. One month later Miss Chisholm submitted her confidential report. She cattishly stated in her cover letter: ‘if I had not been selected for this post [of headmistress] I should probably have asked for your cooperation in some such scheme, as it is I am the more qualified to do it’. She planted a seed in the director’s mind by suggesting that the cookbook could be re-written and expanded to include general household hints ‘by a little group of whom I could be one’. In the body of her four-page report, Chisholm admitted that ‘I have myself taught from it in Domestic Arts Schools and cookery schools and used it in home cookery, … and sold many copies’. She concluded that ‘until a better text book is written, or this is revised as indicated, Our Cookery Book is a fairly suitable text for girls of 12-15 [years]’ (emphasis in original).[41]

Based on this advice, the Director of Education recommended that Our cookery book be used as a school text, provided it was published without any advertisements or recipes containing alcohol. He had already received the government’s permission for Pell to receive royalties, although this was never communicated to Pell. However, the Minister for Education chose to go against the advice of his director and the confidential report prepared by Miss Chisholm and in September 1928 he ordered that schools revert to using recipe cards, which they had not used for thirteen years, until all the remaining 1,900 sets of cards were distributed. In the meantime, a committee of experts, including Miss Pell and Miss Chisholm, was to write a new textbook on ‘cookery, laundry and dietetics, and housewifery’ that the department would publish. The minister was presented with figures showing that, based on the current retail price of 1s 6d, and the demand for 10,000 books per annum, the department expected to make a profit of £311 5s each year.[42]

Pell was outraged by the minister’s directive and wrote a strongly worded letter to the director on 9 October 1928 stating that it would be a retrograde step to use the cookery cards that were printed twenty-seven years ago. She was so keen that Our cookery book remain in schools that she was prepared to forgo some of her profits, writing that ‘if it is a matter of royalties, perhaps some arrangement could be made’. She told the director that Our cookery book was used by students in Tasmania and that exchange teachers visiting from London and Leicester purchased extra copies to take home and use in their schools. She said that there was no need for another book, such as the one that was proposed by the department.

Pell’s letter was acknowledged but ignored. So too was a letter from Miss Grace McLaren, headmistress of the domestic arts college at Geelong, who wrote on behalf of all headmistresses of domestic arts colleges urging the continued use of Our cookery book.[43] Pell was asked to attend a meeting with the co-authors of the new domestic arts textbook on 29 October 1928 and instructed by her superior, Miss Flynn, Chief Inspector of Secondary Schools, to work on the cookery chapters with another cookery supervisor, Miss Keiller.[44] This must have been quite humiliating for Pell to be told to work on the cookery section with another expert after she had written three successful cookery books herself. Sometime in the week following, Flora Pell went on three months’ sick leave.

While on sick leave, this highly motivated and passionate teacher still felt obliged to answer correspondence and check over exam results. When asked by the departmental secretary if she would be able to fulfil her commitment to write her section of the new textbook, she replied that, given she had to continue working while on leave, she felt able to return to work on 14 December and planned to finish her section of the book before the new school year commenced in 1929.[45]

When Pell returned to work, she found that her good friend and colleague Miss Grace McLaren had been doing some lobbying on her behalf. She had sent a circular around to all the cookery centres and domestic arts colleges in Victoria which stated: ‘I urgently request that the use of “Our Cookery Book” be continued in our Cookery Schools’. Senior staff were asked to sign the circular, add their own comments and send it back to Miss McLaren. Most of these circulars were included with McLaren’s letter to the director in October, but sixteen were sent in late and were shown to Pell. One circular was signed by Miss Keiller, a fellow author on the new textbook. When a new Minister for Public Instruction was appointed with the change of government on 22 November 1928,[46] Pell seized the moment and wrote to the Director of Education on 22 December enclosing the circulars, asking that the matter be reconsidered and ‘respectfully and strongly requesting’ the continued use of Our cookery book in schools, now that all recipes containing alcohol and all advertisements had been excised.

Pell’s campaign backfired. The director accepted the advice of his senior officers to adhere to the decision of the former minister and called Pell in for an interview with himself and the three most senior bureaucrats – a tactic he had used six months earlier. The typed notes of the meeting record that Pell defended herself admirably and denied any prior knowledge of Grace McLaren’s actions in sending out the circulars, which were interpreted as undermining the department’s authority. Pell was again reprimanded for allowing Our cookery book to be used in schools and accepting royalties without the department’s permission. She was instructed to continue working on the new textbook.

As an ‘obedient servant’ of the department, Pell worked with her co-authors and submitted her section outline of the new textbook on 12 February 1929. This proposed textbook was never published by the Education Department. On 19 February she arranged for the distribution of the remaining 1,900 sets of cookery cards to the ten metropolitan domestic arts colleges, at the bargain price recommended by the department of 6 pence per set. Ironically, or perhaps mischievously, two headmistresses wrote back to the department to say that they could not purchase their allocation of cookery cards as the students had already purchased Our cookery book.[47] Pell retired from teaching due to ill-health on 8 November 1929. It is not known how long she had been on sick leave before this date.[48] Her friends organised a party in her honour at the Berkeley tea rooms in Little Collins Street on 11 April 1930 to ‘give friends of Miss Pell an opportunity to meet her’.[49] It is amazing to think that a seemingly innocuous cookbook could cause so much trouble and lead to the downfall of a competent and highly regarded teacher and administrator.

From E Sweetman, Charles R Long and J Smyth, History of state education in Victoria, Education Department of Victoria, Melbourne, 1922, p. 260.

When Flora Pell was promoted to Inspectress of Domestic Arts Colleges in 1924, the Argus reported that ‘probably no woman has had greater influence than her on the promotion of domestic happiness among the younger generation in Victoria’, which by that time comprised ‘the greater proportion of householders of today’.[50] Young girls’ limited opportunities to learn the domestic arts provided a strong argument for their place in the curriculum, and the elevation of the home as a ‘dignified activity of national importance’ supported this. Beyond being a blueprint for meals, the turbulent history of Our cookery book attests to the political power of the temperance movement in the 1920s and the authoritarian rule of large government departments. One wonders if loyal, highly skilled teachers with passion and enthusiasm who rise through the ranks of the Education Department would be treated in the same way today.

Endnotes

[1] The Centennial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1888, for example, provided the occasion for the production of a small book, later used by students of the author. MJ Pearson, Cookery recipes for the people, 3rd edn, H Hearne, Melbourne, 1893.

[2] PROV, VPRS 13719/P1 Database Index to Teacher Record Books, 1863-1959, Teacher Record Card 11684 (Flora Pell).

[3] Argus, 7 June 1918, p. 8.

[4] F Pell, ‘Report of the supervisor of cookery’, in Report of the Minister for Public Instruction, 1913-14, Appendix L, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, p. 80.

[5] PROV, VPRS 13719/P1, Teacher Record Card 11684.

[6] Argus, 17 November 1923, p. 21.

[7] J Young, The school on the flat: Collingwood College 1882-2007, Collingwood College, Melbourne, 2007, p. 29. Flora Pell, Our cookery book, George Robertson, Melbourne, 1916. If any readers have used Our cookery book, or know of anyone who has used this book or other cookbooks written by Flora Pell, please contact the author.

[8] Argus, 22 March 1927, p. 14 and 15 November 1928, p. 15.

[9] F Pell, ‘Cookery’, in CR Long (ed.), Record and review of the State Schools Exhibition … 1906, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1908, p. 69.

[10] Federation Index, Victoria 1889-1901: Indexes to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, August 1997 (CD-ROM).

[11] Edwardian Index, Victoria 1902-1913; Great War Index, Victoria 1914-1920; Death Index, Victoria 1921-1985 (all published on CD-ROM).

[12] PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 892/PO Special Case Files, Unit 105, Special Case Number 1213, letter from Pell dated 5 September 1928. I am indebted to Kerreen Reiger for a footnote on page 63 of her book Disenchantment of the home: modernizing the Australian family, 1880-1940, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985, which led me to this file.

[13] ibid., letter from Pell dated 20 December 1915.

[14] Argus, 8 July 1916, p. 6. Additional publicity was in the Argus on 16 July 1916 and the Herald on 11 July 1916.

[15] PROV, VPRS 892/PO, Unit 105, Special Case Number 1213, letter from Pell dated 28 July 1916; Argus, 16 July 1916.

[16] Our cookery book was subject to the Copyright Act 1911 which meant that if Pell did write the book in her own time, then she owned the intellectual property in the work and was entitled to receive royalties. The Education Department had no legal right to prevent her from receiving royalties. However, the way the book was promoted as a textbook written by an experienced and senior cookery teacher was a moral issue they were entitled to comment on.

[17] PROV, VPRS 892/P, Unit 105, Special Case Number 1213, letter from WCTU dated 24 August 1926 and letter from Pell dated 24 August 1926.

[18] ibid., letter from WCTU dated 21 May 1928; The white ribbon signal: offical organ of the Women’s Temperance Union of Victoria, 8 June 1928, p. 85.

[19] PROV, VPRS 892/P, Unit 105, Special Case File 1213, memo from Pell dated 24 May 1928.

[20] The white ribbon signal, 8 September 1930, p. 136.

[21] P Grimshaw, ‘Gender, citizenship and race in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union of Australia, 1890 to the 1930s’, Australian feminist studies, vol .13, no. 28, 1998, p. 201.

[22] Supporters of prohibition were encouraged to wear a white ribbon, hence the name of the newsletter.

[23] Many of these issues and more were discussed at the WCTU annual conventions: see The white ribbon signal, 8 December 1927, pp. 182-3.

[24] P Grimshaw, ‘Only the chains have changed’, in V Burgmann & J Lee (eds), Staining the wattle, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1988, p. 77.

[25] J Smart, ‘A mission to the home: the Housewives Association, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Protestant Christianity, 1920-1940’, Australian feminist studies, vol. 13, no. 28, 1998, p. 219.

[26] ‘Referendums and plebiscites held in Victoria’, in Victorian Parliamentary Handbook, compiled by Victorian Parliamentary Library, 2001. About 43% of Victorians voted to abolish liquor licenses in Victoria in 1930.

[27] F Pell, Miss Flora Pell’s tested cookery dishes and valuable home hints, Specialty Press, Melbourne, 1925, p. 5.

[28] The values of the Housewives Association are discussed in Smart, ‘A mission to the home’, p. 217.

[29] Pell, ‘Cookery’, in Long, Record and review of the State Schools Exhibition, p. 69.

[30] R Ward, Concise history of Australia, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1992, p. 209.

[31] ‘Nation builders’ is a term that was used to describe the men who attended the Convention on Federation. Nicholls quoted in Grimshaw, ‘Gender, citizenship and race’, p. 204.

[32] Pell, ‘Cookery’, p. 69.

[33] Pell, ‘Report of the supervisor of cookery’, p. 80.

[34] Argus, 4 June 1924, p. 6, article by ‘Vesta’, ‘Training of girls’.

[35] Smart, ‘A mission to the home’, p. 220.

[36] J Smart,’The Great War and the “scarlet scourge”: debates about venereal diseases in Melbourne during World War I’, in J Smart & T Wood (eds), ANZAC muster: war and society in Australia and New Zealand, 1914-1918 and 1939-1945, Monash University Publications in History: 14, Clayton, Vic., 1992, p. 69.

[37] Pell quoted by ‘Vesta’ in the Argus, 4 June 1924, p. 6.

[38] Reiger, Modernizing the home, p. 63.

[39] The white ribbon signal, 8 June 1928, pp. 85, 92.

[40] PROV, VPRS 892/PO, Unit 105, File 1213, Education Department file note dated 14 July 1928.

[41] ibid., confidential report submitted 10 August 1928.

[42] ibid., departmental memo dated 5 September 1928.

[43] ibid., departmental memo dated 10 October 1928, letter from Miss McLaren dated 15 October 1928, and memo dated 17 October 1928.

[44] ibid., departmental memos dated 10 October 1928 and 29 October 1928.

[45] ibid., correspondence dated 30 November 1918 and from Pell dated 10 December 1928.

[46] Victorian Premier Edmond Hogan resigned on 20 November 1928 after a no-confidence motion and a censure were carried in the Victorian Parliament. The Leader of the National Party, Sir William Murray McPherson was called to form government, which he did until the Legislative Assembly election of 30 November 1929.

[47] ibid., memo from Miss Flynn dated 18 February 1929; correspondence from Pell dated 19 February 1929, from Richmond Domestic Arts School dated 11 February 1929, and from Fitzroy Domestic Arts School dated 21 February 1929.

[48] PROV, Teacher Record Card 11684.

[49] The party was advertised in the Argus on 17 March 1930, p. 17.

[50] Argus, 31 May 1924, p. 20.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples