Last updated:

‘Family and Social History in Archives and Beyond’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 9, 2010. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Kath Ensor.

This is a peer reviewed article.

In the past, patients in mental institutions or asylums were often estranged from their families. Next of kin were often listed as ‘unknown’. In this paper I show how it is possible to reclaim lost family histories by using primary records in the public domain.

Dolly Stainer was a long-time resident of Kew Cottages. By drawing on archival records frequently used by genealogists to add facts to their own family histories, I was able to discover aspects of the lives of her parents, siblings and grandparents. Many hours were spent scouring government and other sources for references to her family, each discovery offering a clue to further resources. Finally, my searches led me to a published diary of one of her grandfathers, which offered insights into her family that would not be found in official documents.

This paper shows not only how names and dates can be discovered from careful research in the archives, but also how these lost family stories can illustrate aspects of the social history of the day.

We all have a right to know our family history and to understand who we are. In recent decades there has been an explosion of interest in this quest, seen in biographical-style writing, television shows searching for lost family members,[1] and an increased use of archives and libraries. Historian Graeme Davison has argued that the post-1970s boom in family history stems from ‘a widely felt need to reaffirm the importance of family relationships in a society where mobility, divorce and intergenerational conflict tend to dissolve them’.[2]

For many this search for identity is relatively easy. Most of us have at least an oral history and know the names of some of our ancestors. However, this is not so for those who have been separated from their families for many years, incarcerated in an institution. Is it possible to reconstruct their lost family stories, and if so what can these stories tell us about the broader social history of the times?

Dolly Stainer, Little Girl Lost

Kew Cottages: the world of Dolly Stainer[3] launched Dolly into the public domain, introducing her to an audience that previously did not know of her existence. Written by Cliff Judge and Fran van Brummelen, a medical officer and a social worker respectively at Kew Cottages, one of the major institutions for the mentally disabled in Victoria, they reflected on Dolly’s seventy-five years living at the cottages by searching in-house archival material available to them together with oral histories that had been collected. One of the assertions that ran through this book was that Dolly’s birth had not been registered.

What a challenge this presented to me as an historian and genealogist to locate Dolly’s birth record and discover some of her family background. Who was Dolly and where had she come from? With few family details available I decided to see what I could discover from publicly available sources.

At the time of writing this paper any official records pertaining to Dolly’s care and admission to Kew Cottages as well as any possible birth certificate are closed to the public under various Acts relating to access of information at both the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages as well as PROV.[4] My interest therefore turned to Dolly’s mother, Mary, as her records fall outside these closed periods.

For many, the footprints they leave behind are restricted to their entries in the civil records of births, deaths and marriages. Here in Victoria we are very fortunate to have the system of civil registration, which began in 1853 and was devised by William Archer, the first Acting Registrar-General.[5] Each certificate may record extensive family details, and for researchers these details provide great clues as to what other sources should be sought out for information about the family’s history. However, it must be remembered that the information recorded is only what the informant knew and in some cases is very scant or incorrect.

Mary Stainer (née Vincent): Charged with Neglect

I started this research into the life of Mary with just a few pertinent statements gleaned from the previously mentioned biographical work. Firstly, that her name was recorded as Mary Cecelia Stainer (née Vincent). Secondly that she was a ‘notorious prostitute’ with an extensive police record, and finally that she had not registered Dolly’s birth.[6]

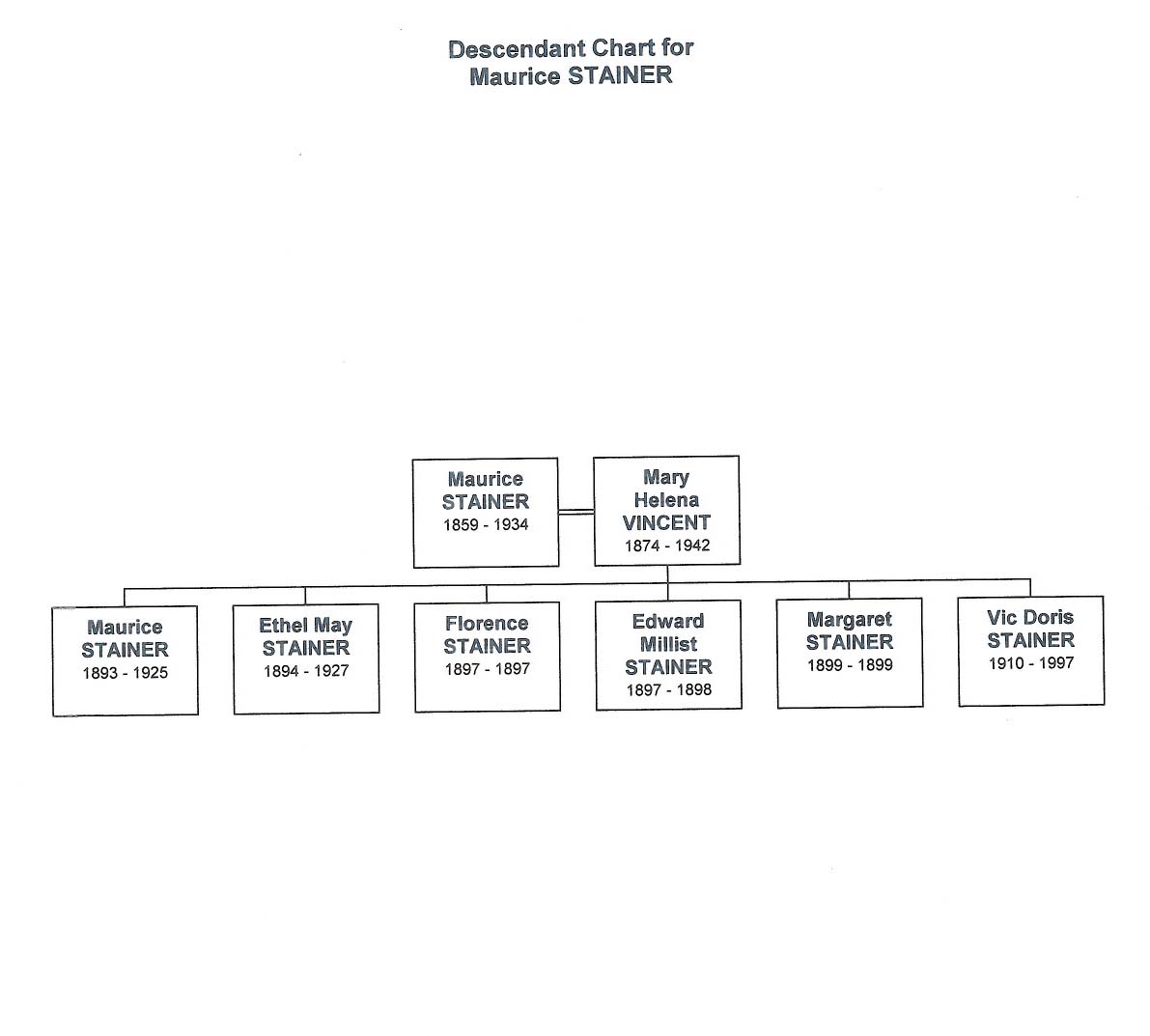

The confusion over her daughter’s birth registration was easily solved. Dolly was recorded on the indexes to births as Vic Doris (sic) Stainer in 1910 and at this time the mother’s name was recorded as Mary Helena rather than Mary Cecelia.[7] I consulted the civil indexes once more to see if I could find any other references to Mary Stainer (née Vincent) but could find neither her birth nor a positive record of her death. Mary had married Maurice Stainer in 1891[8] and Dolly was their sixth child.[9] Three children died as infants[10] and on the occasions of recording the children’s births and deaths Mary’s name was recorded as Mary Ellen, Mary Hellena, Hellena or simply Mary.

The most informative civil record was the marriage certificate, which showed that Mary had married Maurice Stainer, twelve years her senior, on 22 September 1891 in Richmond, Victoria.[11] Mary was just seventeen years old and her place of birth was recorded as Aldershot, England. This explains why her birth could not be located on the Victorian indexes. However, consultation of the indexes to births recorded in the General Registry Office (GRO) in England for several years either side of her reputed birth date also failed to locate this record in either Aldershot or in any other part of England. So, it appears that although it had been alleged that Dolly’s birth was not registered this was in fact incorrect. Instead there was no birth record of her mother Mary Vincent.

In true detective style I set about searching for any references to Mary outside of the civil records. Working from the details given on her marriage certificate I could deduce that she was the daughter of Millist and Margaret Vincent (née Smith) and, as already noted, she may have been born in Aldershot, England around 1874.

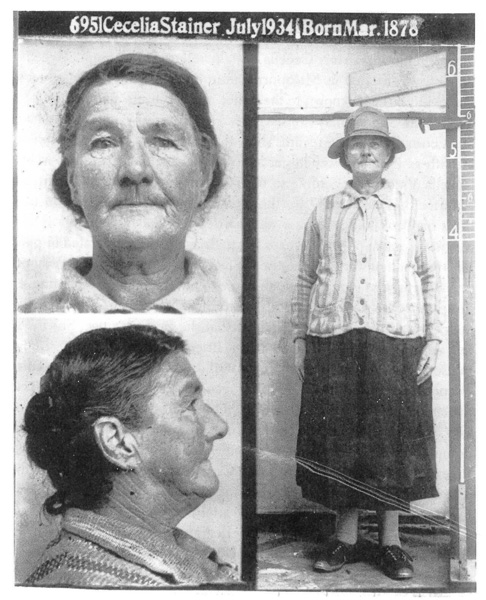

While I did not find any evidence that Mary was a ‘notorious prostitute’, the suggestion that she had an extensive police record could be confirmed by consulting the Victoria Police gazette; there were numerous entries relating to her release from custody, from her first recorded offence in 1903 until at least 1935. She used many aliases including Cecelia Stainer, Cecelia Staines and Mary Vincent, suggesting that the discrepancies in her name that I had noted previously were not accidental.[12] These entries listed not only her many names but also her physical appearance, age, crime and sentence.

Mary was not a hardened criminal; she was an alcoholic and frequently had difficulty supporting herself. After losing three of her children as infants, in 1901 her eldest two children, Maurice and Ethel, at the ages of eight and six both became wards of the state under the Neglected Children’s Act 1887 and were removed from Mary’s care.[13] This Act was responsible for the care of all children in Victoria who were deemed to be neglected or in need of protection by the state. This included children who were begging, wandering at large or found to be living in a brothel.[14] For the first time children in need of care were separated from those who were deemed to be criminal.[15] The secretary of the newly formed Department for Neglected Children became their legal guardians and the children later became known as Wards of State.[16]

The entry in the ward register for Ethel and Maurice reads thus:

Mother: Mary Eleanor Stainer at present in the Salvation Army House. She is of drunken habits and unfit to have charge of the children.[17]

Mary had commenced a downward spiral and these children would never be returned to her. Her mothering skills had failed the community’s, and more importantly the state’s, expectations although she would have one more opportunity to succeed with this after the birth of Dolly (Vic Doris Stainer) in 1910.[18]

An online digitised index to female prisoners in Victoria confirmed her entry as 6951, as recorded in the Victoria Police gazette.[19]

There was a record of a death of a Mary Stainer in 1942 in Victoria[20] but initially there were not enough details to prove that this was the record that I was seeking. The age was correct and the place of birth was given simply as England but the person giving the information on the certificate did not know names of parents, children or spouse. Fortunately, as this Mary Stainer died as a result of an accident there was a coronial inquest into her death.[21]

In summing up, the coroner Arthur Coyte Tingate concluded that Mary Stainer, aged sixty, late of Regina Coeli Hostel, 149 Flemington Rd, North Melbourne,

... died from the effects of injuries received on the 18th day of April 1942 at Flemington Rd near Abbotsford Street North Melbourne in Victoria when she was accidentally knocked down by an electric tramcar.

Some of the evidence that he had heard included a comment from John Richard Barry, a passenger on the tram, who reported:

There was a faint smell of Methylated Spirits about the woman’s person.

Constable Terence Stephen Bible, who was also a passenger on the tram and a witness to the accident, noted:

The deceased was dressed in dark clothing, and visibility was bad owing to brown-out conditions.

This comment suggests that Mary may have been an indirect casualty of the ‘brownouts’ that were common in Melbourne in the middle of World War II and were believed to be responsible for a dramatic increase in traffic accidents.[22] Kate Darian-Smith in her study of Melbourne during this period states that the brownout conditions were policed strictly, all windows were blocked out by curtains and blinds, neon and street lighting was turned off and public transport travelled in darkness.[23]

The voices of the witnesses to Mary’s accident conjure up a picture of her and the circumstances under which she died that would not be found in the indexes of public records. Another clue to her condition is her place of abode, Regina Coeli Hostel. This was a hostel established in 1938 for homeless women.[24] It was Mary Keating, matron of this hostel who identified Mary Stainer’s body.[25]

I believe that there is no doubt that this Mary Stainer was the mother of Dolly and the person whose death I was seeking. It appears that in her later years, after developing a dependence upon alcohol and having over thirty years of brushes with the law, she had become one of the many homeless and destitute living in Melbourne. She died alone, without the support of any family and was buried in the Roman Catholic section of Fawkner Cemetery as Mary Stainor.[26] Even in death her name was recorded incorrectly.

Maurice Stainer, Husband: An Unremarkable Life

Where was Maurice Stainer during these years of Mary’s downfall? Unlike his wife he did not leave a long trail of records that could be consulted. Most references to him that I have found are restricted to births, deaths and marriages. His birth is recorded as being in Ballarat in January 1859, the fourth child of James and Blanche Stainer.[27] His marriage certificate reveals more details. From this document we learn that he married at the age of twenty-nine and his occupation was given as ‘driver’, with his usual address being Latrobe Street, Melbourne.[28]

We have already noted that Maurice was recorded as being the father of six children born in Victoria between 1893 and 1910 and was also registered again as the father when three of them died as infants. His final appearance on these indexes was in 1934 when he died from senility and heart failure at the Victorian Benevolent Home and Hospital for the Aged and Infirm, Royal Park.[29] The authorised agent at the hospital who was the informant on the certificate stated that Maurice was married to Eleanor Vincent (is this yet another alias name or just a simple error?) and that he did not have any children. Such omissions or errors are commonly found on death certificates. Maurice was also buried at Fawkner Memorial Park, but his name was recorded as Maurice Staines (another misspelling) and he was buried in a public grave in the Presbyterian Section.[30]

Civil records are simply facts that are documented in response to a set of questions. Many people do not write diaries, or if they do these are not preserved; they do not appear in newspaper articles or leave behind other written records of their lives. Such was the case with Maurice Stainer. I found just a few other references relating to him outside of the civil indexes. Firstly, he was admitted to the Ballarat Hospital at the age of eleven years in 1869.[31] His last entry in the Sands & McDougall directory is in 1901 when his residence is given as 7 Elizabeth Street, Northcote.[32] Following this all that is known of him is gleaned from welfare files relating to his family. Maurice Stainer himself presumably stayed on the right side of the law, was not brought to the attention of other government departments and no files were created relating to him.

No Happy Home: The Children of Mary and Maurice Stainer

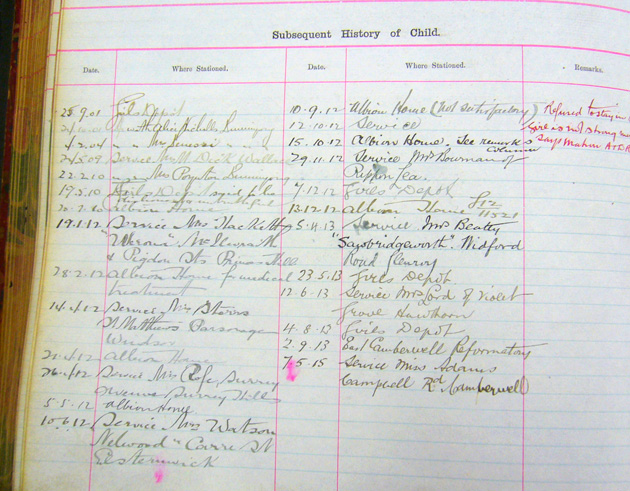

Records created for Mary and Maurice’s eldest two children, Maurice junior and Ethel, when they were removed from their parents’ care in 1901 and became wards of the state, offer glimpses into aspects of their lives. Under the heading ‘Subsequent history of relations’ there are three entries, one noting their mother’s first stay in Coburg Gaol in 1903, another the following year noting that their mother had visited them at their foster home in an intoxicated condition, and a third in 1905 giving their father’s address as care of Mr J Henderson, dairyman, Heidelberg Road, Fairfield.[33] No other instances of family contact are recorded here although they may have taken place.

For Ethel it seems that after her short time boarded out with her brother she was then moved to another family for the next five years. At the age of fourteen she began her working life in service for various families. Over the next six years she worked in service in at least eleven situations, intermingled with several stays at the Royal Park Girls’ Depot. There is just one comment in the remarks section where in 1912 the matron noted ‘Girl not strong in the mind’.[34]

Ethel does not appear on the electoral roll, nor are there any entries for her in the postal directories. She died in 1927 at the Austin Hospital, Heidelberg, aged 33 years.[35] She was single and had no issue. An authorised agent was the informant and did not know Ethel’s usual occupation nor her usual address. It was however recorded that she had suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis for five years. She was survived by both of her parents and younger sister Dolly, but we do not know if they were made aware of her fate. She was buried at Heidelberg Cemetery.[36]

As for Maurice junior, from becoming a ward of the state at the age of eight until his death his life is well documented in public records. After being separated from his sister Ethel, he returned briefly to the Boys’ Depot and then was sent to live with another family for six months until in September 1904 at the age of eleven he was sent to Bayswater House,[37] a home run by the Salvation Army for Protestant boys.[38] This would be the main place that he would call home until he turned twenty.

In the 1908 report for this Salvation Army home it is noted that the boys were rewarded for good behaviour by being allowed home to their families on Sundays. Some boys were monitored in trial work situations while others were placed on probation with their parents. There would be no such rewards for Maurice. He was reported as absconding on several occasions and was returned to the Boys’ Depot for short stays. He had several brushes with the law for fire lighting and on 4 March 1910 he appeared in the Children’s Court in Lilydale accused of having set fire to some private property in Ringwood.[39] He was found guilty and committed to the reformatory school. However, most telling are the comments written in the remarks section of the register of convictions, orders and other proceedings in the children’s court at Lilydale:

Is a bad boy and has developed cunning and has a propensity for fire raising. Has escaped from places several times.[40]

This misdemeanor and the court report would affect his life forever. Two years later, just before his wardship expired, his case was reassessed by the chief secretary’s department. This earlier court report together with two medical reports formed the evidence that was considered in determining his future placement.

He has a congenitally deformed head, a foolish expression: says he burnt down a haystack because his master would not give him more wages, but admits he never asked for more. Cannot say what year this is, nor how much twice five is, altho’ he is (and looks) about nineteen years old. Seems to have depraved sexual tendencies.

Medical certificate signed by J Sandison Yule MD, BS, FRCSE, of Royal Park.

He is a degenerate and has a silly vacant grin on his face and cannot add two and three together correctly though he has been a Ward of the State for several years. He admits writing a most disgusting letter to his sister but does not know why or when he did it.

Medical certificate signed by Dr Gerald Sheahen FRSSE of Brunswick.[41]

He was certified as insane and transferred to Sunbury Hospital for the Insane where his admission is recorded on 28 January 1913.[42] His mental disorder at this time was described as ‘congenital mental deficiency sans epilepsy’ with the supposed cause being alcoholic heredity. We are left wondering if this was a problem that all of Mary’s children inherited and today would have been called foetal alcohol syndrome. Or could this have had a more sinister cause such as syphilis as reputedly suspected, but not proven, at Kew Cottages?[43] Maurice died on 8 December 1925 at the age of 32 years.[44]

By researching the Stainer family as a family historian might research their own family history I was able to unfold a previously unknown story of Mary Stainer (née Vincent) and her immediate family. Mary and Maurice had faced infant mortality on three occasions, and their surviving three children, including Dolly, all suffered from varying degrees of mental disability and were removed from their parents’ care as neglected children. Mary was in and out of gaol frequently for minor offences and right up until the inquest into her death she left a trail of records in the public domain relating to her alcohol addiction.

Similarly, owing to their mother’s alcoholism and lack of mothering skills her children also left a trail of records that have been carefully preserved in the archives. There are detailed ward files containing brief, harsh comments which allow us to read between the lines to imagine some of the situations that the children faced during their childhood. Then there are the relevant records relating to Maurice junior’s admission to the mental health system and his subsequent twelve years spent at Sunbury Mental Asylum. This documentation was created for recordkeeping purposes and only notes minimal observations of him through others’ eyes; nowhere do we hear his voice.

Were the authorities who were charged with Dolly’s care from 1915 to 1997 aware of this tale of a marginalised family, the one Dolly had been removed from? I imagine not. More importantly, what would this information have meant to Dolly herself? Given their history of lost connections, family breakdown and resulting lost family memory, I do not believe that any of Dolly’s immediate family could have answered the question ‘Who do you think you are?’ with much certainty.

What further information could be discovered about the family that Mary married into and her own birth family?

The Stainer Family: Tragedy and Institionalisation

Gold was first discovered in Victoria in 1851, just months after the fledgling colony had officially separated from New South Wales. News of the potential fortunes to be made travelled fast and it was not long before many were fleeing the British Isles to make their fortunes in a land half way across the world.

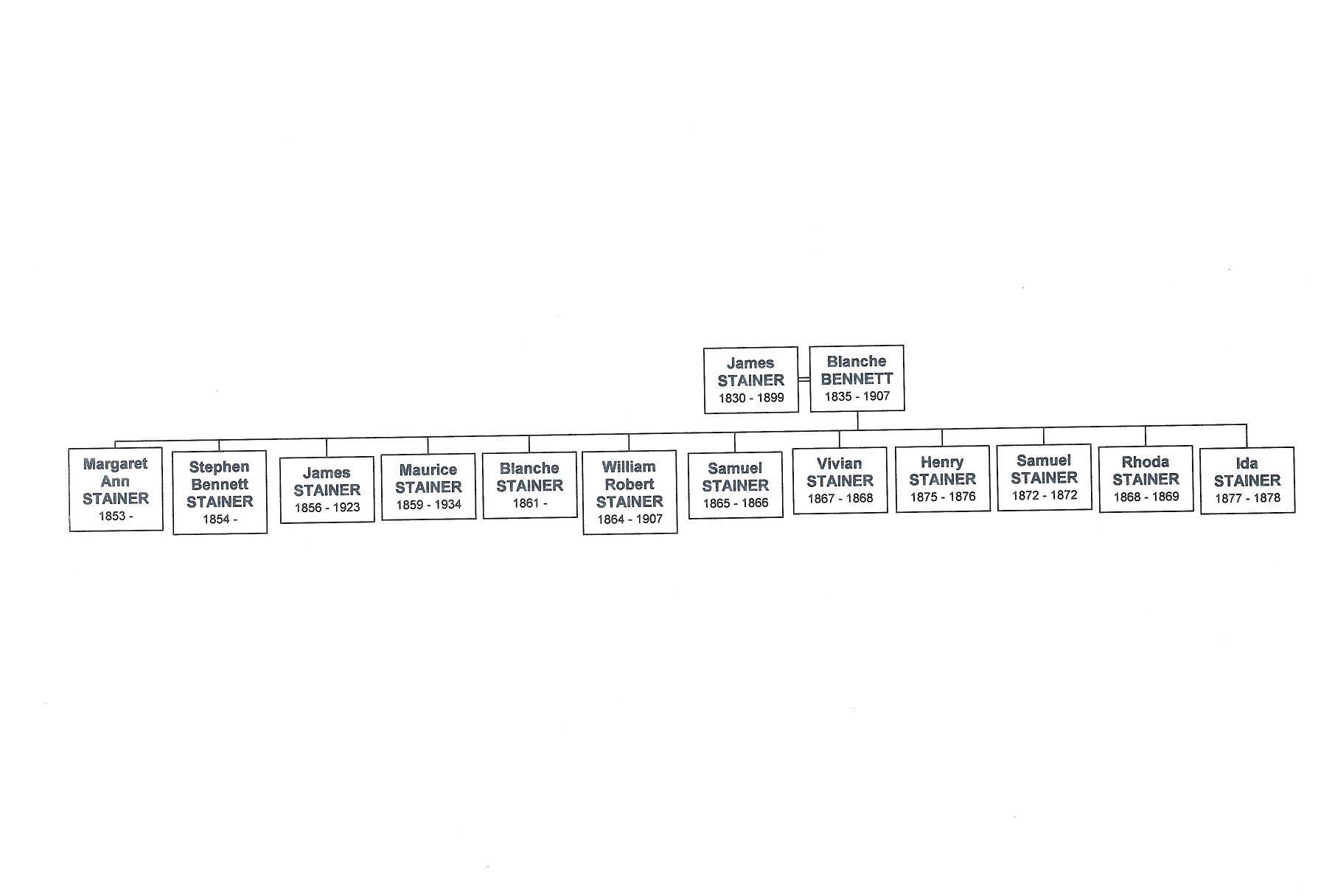

Such was the case with the young couple James and Blanche Stainer of Cornwall, England. They had married in 1853 in Penzance[45] and the birth of their third child James[46] was either imminent or had just occurred when James Stainer senior set sail from Liverpool on 22 July 1856 as a paying passenger on the Mermaid.[47] While onboard he, together with many others, decided to disembark in Geelong.[48] Perhaps they had consulted a map showing routes to the goldfields and realised that this would speed up their journey.[49]

The young parents had spent twelve months apart when Blanche as a twenty-one year old, together with their three children under the age of four years set sail on the Undaunted in August 1857 as assisted migrants.[50] Presumably they were travelling under a scheme to reunite families and Blanche did not have to incur the full fare that James had paid. Perhaps they were covered by a short-lived immigration scheme that Broome refers to whereby settlers could nominate family and friends to join them for a nominal fee and the Victorian Government would pay the difference. This scheme led to huge migration figures over the years 1856 and 1857 but was discontinued because the workforce already in the colonies perceived there to be a work shortage.[51]

In January 1859, in Ballarat, Victoria, the birth of the next baby born to Blanche and James Stainer was recorded.[52] Maurice would be the first of their nine Australian babies born over the next eighteen years. However, consultation of the indexes shows that the last six of these children died in their first year of life.[53] For most of the twenty-six years from the time of her marriage in 1853 until the death of her last child in 1878, Blanche would have been either pregnant or breast-feeding. She would also have been grieving for her six babies who died – a fate that, sadly, was not uncommon for women in this period.

Maurice’s birth certificate is the first documentary evidence we have that his father James Stainer was a miner. By the time their youngest child Ida was born in 1877 the Stainer family had moved from Ballarat to St Arnaud and James was no longer a miner, the gold mining boom had passed and he was now described as a store keeper.[54]

To locate further information about James Stainer during these years I needed to look beyond the civil records. I discovered that he did not make his fortune on the goldfields nor as a shop keeper and was listed in the Victoria Government gazette as becoming insolvent on at least two occasions, in 1869 and 1875.[55] At these times he was described as a hawker. In 1881 he appears once more in the Victoria Government gazette as having applied for an auctioneer’s license.[56]

Times must have become hard for James Stainer, as they did for many Victorians during the 1890s depression, and on 16 March 1898 he was committed to Melbourne Gaol for having ‘no visible means [of support]’.[57] Four months later, at the age of sixty-eight, he was transferred to the Bendigo Benevolent Asylum.[58] This asylum, where he spent his last year, had originally been set up in the 1860s to care for destitute and distressed miners.[59] By the late nineteenth century the majority of the inmates were homeless unemployed rural workers.[60] The authorised agent who gave the information on James’s death record did not know the names of his parents, wife or children.[61]

As for his widow Blanche, we know little about her after her child-bearing days. She was obviously separated from her husband in his last years but we do not know if this was because of economic or health reasons. She died in South Yarra on 20 March 1907 at the age of seventy-two[62] and was buried at Oakleigh Cemetery,[63] survived by five adult children. The lives of some of Maurice’s brothers and sisters can be partially tracked through the indexes of births, deaths and marriages in Victoria. However two branches disappear from the Victorian records; perhaps they were lured to another state in search of work.

This was not the case for James Stainer junior. He did not leave Victoria. His death certificate dated 3 October 1923[64] shows that he died aged sixty-seven at the Hospital for the Insane at Sunbury. This location gave the clue to tracing other public records relating to aspects of his life.

On 29 May 1884, at the age of twenty-eight, James had been admitted to Kew Asylum. The admission book notes that he was a grocer’s assistant and had been born in Cornwall, England.[65] He would remain at this asylum for sixteen years until, on 19 December (just days before Federation), he was transferred to Sunbury.[66] Thirteen years later his nephew, Maurice Stainer was similarly transferred to this asylum. It seems that the information that accompanied James Stainer had not been updated since his original admission in 1884, as the places of residence given for his family members were out of date and he was still described as a grocer’s assistant.

The next record of significance for James is twenty-three years later when an inquest was carried out to determine his cause of death. Here again he is described as single, a grocer’s assistant, and his original diagnosis is noted as ‘chronic mania’.[67] The coroner also noted that ‘he had no known relatives’. Had he had any visitors during his thirty-nine years in asylums or had he been abandoned by his family? We cannot determine the answer to this question just as we cannot tell if his relationship with his nephew Maurice, who was a fellow patient, was ever acknowledged.

It seems that the fortunes, or rather misfortunes, of Dolly’s immediate paternal family had not gone unnoticed and some aspects of their lives had been preserved in official records. The brief notes of their case workers, doctors and justice recordkeepers give us a glimpse of how others perceived them. These perceptions together with the entries in the civil records of births, deaths and marriages have enabled me to discover some of the dynamics of this marginalised family and place them before a backdrop of social history.

Millist Vincent: Mary’s Father Speaks for Himself

What of Mary’s own birth family, the Vincents? I felt confident that I had located the death of Dolly’s mother, Mary Stainer (née Vincent) in 1942.[68] I had also extracted information about her place of birth – Aldershot, England – and the names of her parents Millist and Mary Vincent (née Smith) that she had given at the time of her marriage in 1891.[69]

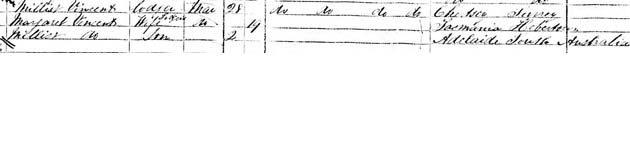

Mary’s father was reputedly a soldier and had an unusual forename, Millist, which was also given to one Mary’s sons, Edward Millist Stainer.[70] I decided to search some of the historic databases for this name and discovered two people called Millist Vincent in the 1871 census of England living at the same address in Sheffield, Yorkshire.[71] They were father and son. Millist Vincent was a soldier aged twenty-eight years who was born in Chertsey, Surrey. His nineteen-year-old wife Margaret was born in Tasmania while Millist Vincent junior was listed as a two-year-old son having being born in Adelaide, South Australia. With this unusual name, correct occupation of soldier and with an Australian connection circumstantial evidence was mounting that this was Mary’s family.

The information contained on these three lines was a great find. Firstly, it explained the absence of Mary’s birth registration in the indexes, as records relating to this family during their father’s military career in the British army would most likely be found in the regimental returns rather than in civil records.[72] It also suggested that further research may be needed in Australia and England.

I was hoping to discover aspects of Mary’s parents’ life stories to gain a deeper understanding of her family background before her marriage. Firstly, I would need more evidence before I could conclude that this family that I had discovered in the 1871 Census was the correct one. I checked for the birth of Millist junior in the indexes to South Australian births[73] without success and had similar negative results in the South Australian and Tasmanian indexes searching for the marriage of his parents. This lack of registration in the civil records for both of these events once again suggested I should look in the regimental returns. The birth of Millist Vincent senior was much easier to trace. His birth was recorded in the GRO indexes to births in England as having occurred in the first quarter of 1843 in Chertsey, Surrey.[74] I still needed to prove that this was Mary’s family that I was researching before I leapt back another generation.

Searching divergently I then located a published memoir of a Millist Vincent in the State Library of Victoria, 21 Years in the Queens Army.[75] Could this be the clue that I was searching for? The discovery was invaluable. It not only confirmed that this was the family that I was seeking but also gave me the voice of Millist Vincent himself rather than someone else’s perception of him.

This book had been published in 2007 by one of Millist’s descendants and was a memoir he had written himself based on his diaries between 1860 and the 1880s and also included some personal details of his life before and after his time in the army. Of major relevance to me was where he was in 1874 when Mary was allegedly born. In his memoir he notes that on 12 September 1873 the regiment left by rail for Aldershot, mentioning that ‘all the women and children’s stores and sick left Chester the day before for Aldershot’ (p. 77). This not only placed Millist but his whole family in Aldershot, Mary’s reputed place of birth. There was no doubt that this was the correct family. What other clues to the family’s life story could I discover from this memoir?

When talking of his own birth the author confirms that he was an only child, born on 28 February 1843 in Chertsey, Surrey (p. 1). His father died two years later and his mother when he was ten years old (p. 2). He comments about his mother, ‘I had a good kind and loving mother who was very fond of me’ (p. 2). This simple statement tells us more about his relationship with his mother than would be recorded on her death certificate.

After being orphaned Millist spent time living with various contacts of his extended family and worked as an apprentice groom. This was not a happy time for him and he was treated harshly. However life changed dramatically for him after he walked to London with a friend to join the 43rd Regiment (p. 14). Over the next two decades his service in the Imperial Army took him to places as diverse as Ireland, New Zealand, Australia, Afghanistan and India (pp. 16-57). He was involved in military service across the globe from the Maori Wars in New Zealand to the Afghan Wars and served alongside General Kitchener, who later gave him a reference (see introduction).

For a researcher interested in military history this memoir was clearly invaluable. However, my interest was in his family history and it was personal references for which I was searching.

A significant family event occurred in 1868 while Millist was posted in Hobart. Here he met Margaret Smith who was to become his wife. At the same time he was offered a contract to sign up to the regiment for twenty-one years in return for £10 and two weeks’ leave (p. 62). The young couple took advantage of this leave and they were married. Millist wrote in his memoir:

So on 28th February 1868 I got married to a young girl who has made me one of the best of wives and mothers a man could be blessed with. (p. 62)

Once again this personal comment says much more than an entry in an index or on a marriage certificate.

He notes briefly that their eldest son was born in Adelaide on 27 March 1869 (p. 67). This was Millist Vincent junior, who had appeared on the 1871 census in England. Family details such as children’s births were not meant for this memoir and do not feature. However, in summing up his memoir in an entry which appears to be dated around 1913, Millist writes: ‘We have had a family of 16 children three of whom are dead and 13 alive and as well we have 4 grandchildren’ (p. 114). Could these grandchildren be the children of Mary and Maurice Stainer living in poor conditions in Victoria or was he referring to other grandchildren?

Millist ends his memoir with a firm statement about their financial affairs:

Me and my wife has often found it very hard to make ends meet with our large family but we can say like the Village Blacksmith that we owe not any man for we don’t owe a penny to anyone in Hobart and I hope that we never will. (p. 114)

A Family History Discovered and Connected

My research into Mary’s family and the family into which she married has revealed much. Mary Stainer is no longer just the mother who neglected her children. She is no longer just a homeless woman with a long criminal record who was knocked down by a tram while she was intoxicated. By researching her family tree she can be placed in the context of her family and the social times.

Mary had been born into a family that travelled the world with her father’s regiment for many years. As a teenager she left the security of her family that had settled in Tasmania and made her way to Victoria where she married at the age of seventeen with the permission of a justice of the peace.[76] We do not know if she maintained any contact with her parents or large birth family, although it is noted on her certificate that a William Vincent was a witness to her marriage. She certainly would not receive much if any support from the Stainer family into which she had married.

Mary and Maurice saw three of their infant children die, the other three removed from their care, and two of these certified as insane. Alcohol dependence was Mary’s downfall. This illness, together with the economic depression of the 1890s, saw her fall upon the mercy of the welfare and criminal systems. It is through these sources that we see others’ perceptions of her. Similarly her two eldest children who were placed in care are recorded in the welfare books and her son then left a trail of records in the mental health system. We will have to wait for several years until the records of her youngest child Dolly are available for public scrutiny.

Without these welfare records our knowledge of the Stainer family would have been limited to the entries in the civil indexes to births, deaths and marriages. By thinking divergently I have been able to retrieve and retell some of this marginalised family’s history. However, in contrast to this the Vincent family is well documented through both military and personal records. By combining these with other resources I have been able to recreate an image of their history over three generations.

My interest in this family was initially sparked by trying to discover who Dolly Stainer was. Her biographers Cliff Judge and Fran van Brummelen had explored her life in an impressive piece of historiography against a backdrop of Kew Cottages from her admission date in 1915 until her death in 1997. The baton passed to me and I have shown how it was possible to trace aspects of the family story of her grandparents, parents and siblings. This not only gives Dolly a family history outside of the mental health system but also makes her ancestors players in scenes of migration to Australia, gold mining, military history, infant mortality, mental health services and much more.

Endnotes

[1] For example, the British series Who do you think you are? (Wall to Wall, 2004- ) and its offshoots, and the Australian series Find my family, screening on the Seven Network.

[2] G Davison, The use and abuse of Australian history, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 2000, p. 82.

[3] C Judge & F van Brummelen, Kew Cottages: the world of Dolly Stainer, Spectrum Publications, Melbourne, 2001.

[4] Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1996, Public Records Act 1973. Privacy laws restrict public access to birth certificates for 100 years or until the person has died, whichever is the greatest: see Access policy on the Births, Deaths and Marriages website, available at <http://www.bdm.vic.gov.au/utility/about+us/legislation+and+policies/access+policy/>, accessed 13 June 2013.

[5] See History of the Registry, on the Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages website, available at <http://www.bdm.vic.gov.au/utility/about+us/history+of+the+registry/>, accessed 13 June 2013.

[6] Kew Cottages: the world of Dolly Stainer, p. 7.

[7] Victorian Edwardian Index 1902-1913 on CD-ROM, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Melbourne, 1997.

[8] Federation Index, Victoria 1889-1901: Indexes to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, August 1997 (CD-ROM).

[9] ibid. The births of Dolly’s five elder siblings are listed as: 1893/16249, 1894/19692, 1897/14070, 1898/17153, 1899/16249.

[10] ibid. Deaths 1897/10344, 1898/18097, 1899/5052.

[11] ibid. Marriage 1891/6373.

[12] Victoria Police gazette, 1903 Supplement following p. 497; 1905 Supplement following p. 471; 1907 Supplement; 27 February 1909, p. 3 of Supplement; 23 August 1934, p. 880; 20 December 1934, p. 1315; 20 December 1935, p. 406.

[13] PROV, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Registers, Unit 62, Item 26743, and Unit 62, Item 26744.

[14] D Jaggs, Neglected and criminal: foundations of child welfare legislation in Victoria, Phillip Institue of Technology, Melbourne, 1986, p. 25.

[15] ibid., p. 55.

[16] ibid., p. 57.

[17] PROV, VPRS 4527/P, Unit 62, Item 26743.

[18] Victorian Edwardian Index, 1902-1913, Birth 1910/1517.

[19] PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 10879/P0 Alphabetical Index To Central Register of Female Prisoners 1857-1948, Unit 2, p. 108. This index has been digitised and can be viewed on the PROV catalogue, available at <www.access.prov.vic.gov.au/public/component/daPublicBaseContainer?component=daViewSeries&entityId=10879&consignment=P0000>, accessed 11 June 2013.

[20] Victorian Death Certificate 1942/4433.

[21] PROV, VPRS 24/P Inquests into Deaths in Victoria, Unit 1444, File 1942/606. Further evidence discussed in the text is also from this inquest.

[22] A Brown-May & S Swain (eds), The encyclopedia of Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2005, p. 92.

[23] K Darian-Smith, On the home front: Melbourne in wartime 1939-1945, 2nd edn, Melbourne University Press, 2009, p. 19.

[24] See A O’Brien, A call to mission: Catholic agencies and older homeless people, Catholic Services Victoria, 205, p. 21. This paper is available on the CSSV website, available at <http://www.css.org.au/papers.html>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[25] PROV, VPRS 24/P, Unit 1444, File 1942/606.

[26] Fawkner Memorial Park, Roman Catholic Compartment GA Grave 324. Details of deceased persons at Fawkner Memorial Park can now be searched online, available at <http://www.fcmp.com.au/index.asp?page=deceasedstandard.asp>, accessed 13 June 2013.

[27] Victorian Birth Certificate 1859/2351.

[28] Victorian Marriage Certificate 1891/6373.

[29] Victorian Death Certificate 1934/4315.

[30] Fawkner Memorial Park, Presbyterian Compartment C Grave 1226.

[31] Ballarat Hospital Admissions Register 1856-1913, published by the Genealogical Society of Victoria, 2003.

[32] Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and suburban directory for 1901, Sands & McDougall Ltd, Melbourne, 1901, p. 432.

[33] PROV, VPRS 4527/P, Unit 62, Item 26743.

[34] PROV, VPRS 4527/P, Unit 62, Item 26744.

[35] Victorian Death Certificate 1927/5958.

[36] ibid.

[37] PROV, VPRS 4527/P, Unit 62, Item 26743.

[38] PROV, VA 1467 Children’s Welfare Department, VPRS 5690/P0 Annual Reports of the Secretary and Inspector of the Department for Neglected Children and Reformatory Schools, Report for 1908.

[39] PROV, VPRS 4527/P, Unit 62, Item 26743.

[40] PROV, VA 4099 Lilydale Courts, VPRS 1422 Children’s Court Registers, Unit 1, Item 1/1910.

[41] PROV, VA 2843 Sunbury Hospital for the Insane, VPRS 8259/P1 Admission Warrants – Male Patients, Unit 7, Item M 1532.

[42] PROV, VA 2843 Sunbury Hospital for the Insane, VPRS 8236/P1, Register of Patients, Unit 3, Item 185.

[43] Judge & van Brummelen, Kew Cottages, p. 24.

[44] Victorian Death Certificate 1925/155225.

[45] General Registry Office (UK), Marriages, Jul qu. 1853, vol. 5c, p. 573.

[46] General Registry Office (UK), Births, Jul. qu. 1856, vol. 5c, p. 290 (these certificates from England were not obtained as the information contained on them would add little to the family story apart from giving a specific date for the events).

[47] PROV, Index to Unassisted Inward Passenger Lists to Victoria 1852-1923, searchable online via the PROV website, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/unassisted-passenger-lists>, accessed 26 March 2020.

[48] PROV, VPRS 7666 Inward Overseas Passenger Lists (British Ports) 1852-1923 (microfiche), Fiche 114, p. 002.

[49] For example, JB Philp (lithographer), Map of the roads to all gold mines in Victoria, Melbourne, c.1853.

[50] PROV, Index to Assisted British Immigration 1839-1871, searchable online via the PROV website, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/assisted-passenger-lists>, accessed 26 March 2020.

[51] R Broome, Arriving, The Victorians, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, McMahons Point, NSW, 1984, p. 89.

[52] Pioneer index. Victoria 1836-1888: index to births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, Registry of Births, Deaths and Mariages, Victoria, 1998 (CD-ROM), Birth 1859/2351.

[53] ibid., Deaths 1866/181, 1868/2979, 1869/272, 1872/147, 1876/4251 and 1878/3553.

[54] Victorian Birth Certificate 1877/14235.

[55] Victoria Government gazette, 11 June 11 1869, p. 877 and 1 October 1875, p. 87.

[56] ibid., 29 April 1881, p. 1149.

[57] PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 515/P0, Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 51, p. 464. This page has been digitised and can be viewed on the PROV website, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/justice-crime-and-law/register-male-and-female-prisoners-1855-1947>, accessed 26 March 2020.

[58] Bendigo Benevolent Asylum: inmates register 1860-1941, Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies, Bendigo Branch, 1995, Book 2 (microfiche).

[59] ibid.

[60] C Fahey, ‘Abusing the horses and exploiting the labourer’, Labour History, no. 65, November 1993, p. 109.

[61] Victorian Death Certificate 1898/12364.

[62] Victorian Death Certificate 1907/2917.

[63] Oakleigh Cemetery Database, record 1949, plot 1652.

[64] Victorian Death Certificate 1923/16956.

[65] PROV, VA 2840 Kew Asylum, VPRS 7398/P1, Case Book of Male Patients 1871-1912, Unit 9.

[66] PROV, VPRS 8236/P1, Unit 2, p. 87v, no. 762. This record has been digitised and can be viewed through the PROV catalogue, available at </archive/RG8236-P0001>.

[67] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 1034, File 1923/287 Inquest into death of James Stainer.

[68] See note 20 above.

[69] See note 11 above.

[70] Victorian Birth Certificate 1897/14070.

[71] 1871 Census Return of England and Wales, Class: RG10; Piece: 4663; Folio: 91; Page: 16; GSU roll: 847222. UK Census Collection available through ancestry.com.au, available at <http://www.ancestry.com.au>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[72] E Galford, The genealogy handbook: the complete guide to tracing your family tree, Marshall Editions Ltd, London, 2001, p. 69.

[73] South Australian births, registrations 1842 to 1906, South Australian Genealogy & Heraldry Society, 1998 (CD-ROM).

[74] General Registry Office, Births, 1st qu. 1843, Vol. 4, p. 76.

[75] M Vincent, 21 years in the Queen’s army, ed. by MV Genery, Mark Genery, Coburg, Vic., [2007]. Further references to this work are given in the text.

[76] Victorian Marriage Certificate 1891/6373.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples