Last updated:

‘Everything Changes: Piecing Together Evidence for a Story of Loss and Absence’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 9, 2010. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Janet Marles.

When a World War I veteran, who has been blinded in one eye on the battlefields of France, drives his car into a tram, he is killed. He leaves behind a wife and three daughters. It is 1937. Tragically, less than four years later the girls’ mother dies from a mysterious illness, and the girls are boarded in a succession of houses hundreds of kilometres away, disconnected from their past. More than sixty years go by, and the youngest daughter is handed a shoebox containing documents that fill in some of the pieces of her story. This sets in train a journey of discovery that is at once geographical and emotional. After locating inquest documents at PROV, the woman’s daughter makes an interactive online documentary about the shoebox, and an online audio dramatisation of the car accident as a pivotal event in her mother’s life. The present article describes the process of unlocking the evidence, both personal and archival, to produce this work.

A Family Tragedy

On a wet September evening in 1937, Donald McDonald drives his car into a tram and dies instantly. He leaves behind a wife and three daughters. Less than four years later, his wife Clara dies from a mysterious illness. The girls, Gwendoline aged seventeen, Marjory aged fourteen, and Heather aged ten, are put under the guardianship of their father’s brother, Uncle Jock, a stock and station agent who lives in Kaniva, in central-western Victoria.

A silence descends over the family, as the old ones feel it is best not to upset the girls by talking about their unfortunate situation. Uncle Jock insists the girls are not to be separated. Yet it is the World War II and accommodation of any sort is very scarce. So they are boarded in a succession of houses hundreds of kilometres away in Geelong. For Heather, the youngest, it is a dozen homes in eleven years. With only scraps of information and two small photographs, she ponders her origins and the cause of her mother’s death for over sixty years until, unexpectedly, at the age of seventy-two, she is handed a shoebox containing documents that fill in some of the pieces of her story.

As Heather’s daughter I share her desire to uncover more of the family history. Inspired by the detailed information contained in the shoebox, together we undertake a genealogical and emotional journey that involves visiting relatives, historical buildings, community halls, cemeteries, archives and key locations from her childhood. Gradually fragments of evidence are unearthed until a more precise picture of her past can be drawn.

The Shoebox

Over the Easter break of 2002, my mother Heather visited Kaniva, a small town in the wheat-growing district of the Wimmera, in order to meet relatives as yet unknown to her. One of her grown nephews accompanied her. She had lost touch with her country relatives since her parents’ deaths and had only returned to the district three times between 1950 and 2002.[1] On this, her fourth trip, a most extraordinary event occurred.

At one of the family dinners arranged for Heather and her nephew they met, for the first time, Heather’s guardian Uncle Jock’s grandson, Grahame McDonald. The following day Grahame decided to finally eradicate the white ants in his mother’s shed. As he was cleaning out the contents of this shed Grahame came across a fifty-year-old shoebox. On the lid, written in pencil, were the initials DN & JAS McD.

Grahame sifted curiously through the contents in the shoebox, but could not recognise any of the names referred to in the papers. Taking the shoebox inside, he asked his mother about it, who thought it might perhaps belong to the parents of Heather, the distant relative Grahame had met the night before.[2] Grahame immediately took the shoebox to where Heather was staying. He confessed later that the contents of the shoebox seemed so personal he felt he was prying, and was anxious to deliver it to Heather as soon as possible.[3]

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Inside the shoebox Heather discovered records: account books, cheque butts, letters, and other documents stored by her guardian Uncle Jock relating to her and her sisters’ board and keep. The shoebox also contained the wills of both her parents plus probate documents filed at the time of their deaths. There were documents concerning land taxes and Donald’s horse-breeding activities, and the purchase documents dated 1937 for the Moolap property where Heather was living when her father died. This property known as Abdullah Park is a fifty-acre horse stud located just outside Geelong. The sale documents revealed Heather’s father died just eleven weeks after the family moved from the Wimmera to Abdullah Park.

The documents in the shoebox were all dry fiscal records dating from 1922 to 1950, yet to Heather these papers were a tangible link to her long deceased parents. Their discovery enabled her to touch and scrutinise items used and written by her mother and father more than sixty years before. As Margaret Gibson explains in her book on memory and mourning, ‘for the bereaved objects can transpose into quasi-subjects, moving into that now vacant bereft place’.[4]

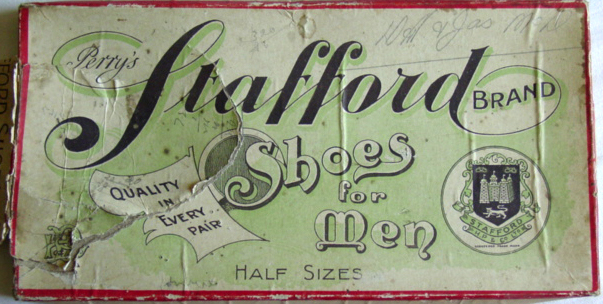

Photograph by Janet Marles.

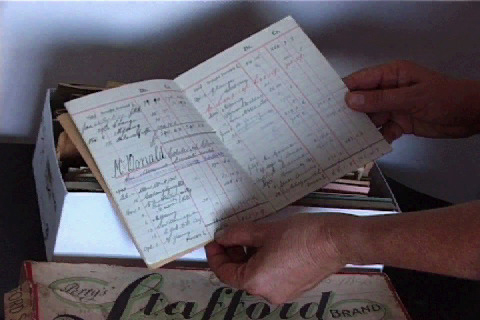

This humble collection of papers told Heather much about the choices that had been made for her as an orphaned child. There were ledgers with dates indicating when the girls moved from one boarding house to another and itemisations of their costs and weekly board. There were letters to bank managers and letters from the girls themselves requesting funds from Uncle Jock. One cheque butt for twenty pounds dated 31 July 1941 had Uncle Jock’s poignant notation: ‘advance to carry on’. This cheque was written ten weeks after the death of Heather’s mother Clara.

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Heather’s recall for the events of her childhood is fragmentary. Being so young when she was orphaned, she was frequently unaware of situations occurring around her and was often not told what was happening or why. The shoebox, too, is full of fragments, tiny time capsules of information and random records. There is no chronology, no diary, no personal memoir or intentional biography. It is just a collection of documents, the daily detritus we usually discard once it is no longer useful.

Yet these documents were kept, and serendipitously presented to Heather, initiating her quest to discover more. She had always been hungry for knowledge and details about her parents, details that were not forthcoming even from family members who were older and who had witnessed events as they transpired. Now, here finally was some information and it whetted her appetite to uncover more. Why had particular decisions been made? What motivated certain actions? Was it now possible, after such a long time, to find the answers to some of her questions?

A Genealogical Journey

I started to document Heather’s process of discovery, and began the lengthy task of searching for photographs and records, conducting interviews, visiting key localities and piecing together explanations for missing portions of her history.

One of my first archival searches was with the Geelong Historical Society. Although Heather and her sisters did not attend either parent’s funeral, Heather knew precisely the dates on which each had died. The Geelong Historical Society located the relevant death and funeral notices for her parents from the local newspaper the Geelong advertiser: Donald Neil McDonald (23 October 1893 – 9 September 1937) and Clara McDonald née Bell (3 September 1898 – 20 May 1941).[5]

Nothing new surfaced to clarify the mysterious illness that killed Clara at just forty-two years of age. However the Geelong advertiser did contain two small articles on Donald’s motor vehicle accident and these both referred to an inquest being opened to investigate the circumstances of his death.[6] Heather had not known an inquest had been conducted and believed her guardian, Uncle Jock, was also unaware.[7]

Inquest Opened

An Inquiry into the death of Donald McDonald, aged 44 years, married, of Moolap, who was killed when his motor car came into collision with a tramcar in Ormond road, East Geelong, on Thursday evening, was opened yesterday by Mr. F.G.H. Ritchie, deputy Coroner. Evidence of identification was taken, and the inquest was adjourned to a date to be fixed. The Deputy Coroner inspected the wrecked motor car and damaged tram.

With this newfound knowledge and with so many strands of Heather’s childhood story beginning to come together, she and I planned another trip to the Wimmera in November 2005. On this occasion my eldest sister accompanied us. Anna Haebich explains this type of travel:

The quest for the past has spawned a new tourist niche – genealogical, roots or homeland tourism – that sits somewhere between pilgrimage and heritage tourism. The search engines of the world wide web are the departure points for these journeys. The destinations are off the beaten track, places where travellers seek emotional, personal and even spiritual contact with the past, as well as museums and archives where they search for genealogical and historical facts to embellish their memories.[8]

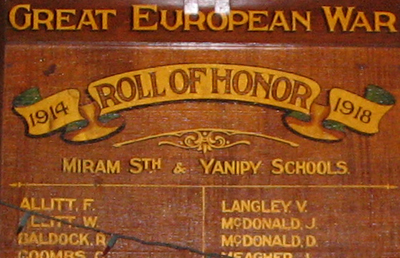

Flying into Melbourne and hiring a car, the three of us drove 400 kilometres northwest to Kaniva. We went to the relative Heather and her nephew had stayed with in 2002. From there we met family and visited districts Heather remembered from her childhood. We visited the 2500-acre property at Miram South where Heather lived until she was six years old, and the one-teacher primary school at Bill’s Gully she attended for her first year of schooling. Now a community hall, this building houses a roll of honour naming the men from the district who fought in the World War I. Heather’s father Donald McDonald and his older brother James are both listed.

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Earlier that day we had visited the Kaniva cemetery. The cemetery has impressive entrance gates and two distinct areas of burial, one for Catholics, the other for Protestants. All the McDonalds were in modest, unadorned graves that reflected their Protestant origins, except for Heather’s grandparents John and Mary McDonald (née McLean) whose grave was comparatively stately. It was adorned with a tall marble column between the two graves, crowned with a draped urn.[9]

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Among the McDonald clan headstones we found the grave of James McDonald. James was one of Donald’s five brothers. He was five years older than Donald and the only other McDonald brother who fought in the World War I. Both James and Donald were badly injured at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916; they made it home, yet both died prematurely. James remained unmarried and died aged forty-eight on 15 July 1937, coincidently just eight weeks before Donald. The initials JAS on the shoebox lid (see image above) refer to James McDonald’s deceased estate.

Leaving Kaniva we travelled east forty kilometres to the region around the town of Nhill where Heather’s mother’s clan, the Bells, hailed from. Heather’s maternal grandparents Tom and Margaret Bell (née Rainer) raised eight children on their property at Kinimakatka – six girls in a row followed by two boys. Heather’s mother Clara was their youngest daughter.

In Nhill we were treated to a family reunion dinner with a gathering of twenty-seven relatives. Some of Heather’s cousins had travelled from as far away as South Australia and Perth to be there to meet her. This gesture of unity had profound significance for Heather who, as an orphaned child, had often felt disconnected, distanced, vulnerable and fragmented.

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Reading the Inquest at PROV

After some days with the Nhill relatives we journeyed back to Melbourne. My sister flew home, and Heather and I drove to the Public Record Office in North Melbourne. Weeks before I had ordered the inquest documents of Donald McDonald’s fatal car accident of 9 September 1937, and we were scheduled to view them. Arriving at the PROV building I was relieved to be through the unfamiliar Melbourne traffic and eager to see the inquest documents.

Heather, however, was becoming increasingly reticent. She was suddenly disinclined to see these documents. Not wanting to upset her I suggested we get a coffee in the cafe adjacent to the entrance. This she readily accepted. Heather’s reticence stemmed from her childhood of grief and her family’s disinclination to speak to the girls about their tragic situation. They were boarded with strangers hundreds of miles from the rest of the extended family and discouraged from asking questions. Heather received no grief counselling and had been brought up with the philosophy, common for the time, of ‘just get on with it’.

Yet there was so much she wished to know. What ailment had killed her mother? Was it grief and stress or a disease of some sort? What were her parents like as people? How did they get along together? How was her father able to surge ahead financially when he had been so badly injured in the war? Was there any truth to the family whisper that her mother’s grandmother was Aboriginal? Why hadn’t Aunty Addie and Uncle Alec taken the sisters in when they moved to Geelong to retire?

These questions and many like them are the kind of enquiries children make in an attempt to understand their parents, their families, who they are, and how they too fit in. With Heather’s family’s unwillingness or inability to talk to the girls about their situation, these questions and many more remained unanswered.

Once we had finished our afternoon tea Heather agreed we should go to the reception counter. Two attendants greeted us. I showed one of them the file number I had been sent[10] and the letter identifying that we were here to view documents. Again Heather hesitated but the staff, in their professional way, had begun to process us. The force of the bureaucracy took over and we passively followed. We were shown into a side room, asked to leave our bags in a locker and to wear the white gloves provided. Once ready we were shown through a locked door and instructed to walk the length of the room to the last counter where our file would be retrieved for us.

The document viewing room is a large space; to the left are rows of tables and chairs similar to libraries before the digital era, to the right the staff have their offices surrounded by rows of files and cabinets. We approached the last counter where a man in his late twenties greeted us. We told him why we were there and showed him our document number. He asked us to wait while he located our file. A short time later he returned with a plastic bag containing a few sheets of paper and indicated we could go to one of the tables to view the documents. He kindly suggested we take as long as we needed.

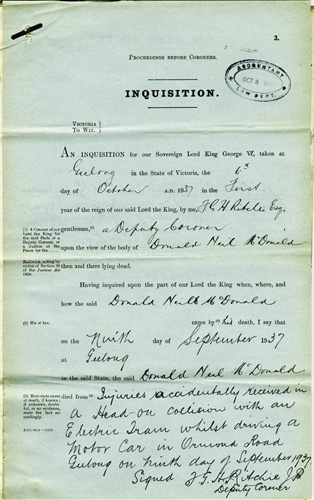

Heather held the plastic bag containing the documents and we sat at one of the tables. She opened the bag. There were sixteen pages, twelve handwritten and four typed. We read each page carefully. Heather occasionally read aloud or expressed small surprise, but other than this she remained calm, contained, stoic. Her emotions were held tightly in. This was the first time either of us had seen inquest documents and we were amazed at the precise details they contained. There was a cover page with the document number, date, place, name of deceased, and name of the coroner, followed by a statement of cause of death as determined by the deputy coroner. The language used in the documents dispelled any possible doubt that these were significant papers.

Proceedings Before Coroners

Inquisition

Victoria

To WitAn Inquisition for our Sovereign Lord King George VI, taken at

Geelong in the State of Victoria, the 6th

Day of October A.D. 1937 in the First year of the reign of our Lord the King, by me,

F.G.H. Ritchie Esq,

A Deputy Coroner

Upon the view of the body of Donald Neil McDonald

then and there lying dead.

Having inquired upon the part of our Lord the King when, where and

How the said Donald Neil McDonald

came by his death, I say that

on the Ninth day of September 1937

at Geelong

in the said State, the said Donald Neil McDonald

died from Injuries accidentally received in

a head-on collision with an

Electric Tram whilst driving a

Motor Car in Ormond Road

Geelong on ninth day of September 1937.

Signed J.G.H. Ritchie JP

Deputy Coroner

There was a report from police constable WW Kuhne who attended the scene of the accident; a report from the deputy coroner requesting an autopsy; an identification statement sworn and signed by Donald’s brother John Fraser McDonald (Uncle Jock); one witness report from Lewis O’Sullivan, the licensee of the Criterion Hotel Geelong, who was the last person to speak with the deceased; three witness reports from Herbert Deller, the driver of the horse-drawn dray involved in the accident; a report from the medical practitioner James Ernest Piper who conducted the post mortem; two witness reports from Percival Wallis Fuller, the driver of the tram that collided head-on with Donald’s automobile; one witness report from Keith Martin Atkins, the conductor of the tram; a second statement from 1st Constable William Walter Kuhne of East Geelong Police; and a backing page with identification and file record numbers. All in all, sixteen pages containing the opinions, evidence, and statements from eight people.

These pages of the Coroner’s Inquest, stored in the archives for sixty-eight years, revealed some surprising details. Donald had consumed three small gins at the Criterion Hotel approximately half an hour before the accident. The publican Lewis O’Sullivan considered him to be perfectly sober, however, and made the comment that Donald only had sight in his left eye. Donald had sustained a severe head injury during the war, resulting in the loss of sight in his right eye.

At the time of Donald’s car accident the weather conditions were wet and windy, daylight was fading and visibility was poor.[11] Heather’s guardian John Fraser McDonald identified the deceased as his brother Donald on 10 September 1937. He stated that the last time he had seen Donald was on 17 July 1937. This was two days after their brother James McDonald had died. Donald had returned to Kaniva to attend James’s funeral.

Police Constable Kuhne, who attended the scene of the accident, reported that the front portion of the car and engine were driven back into the vehicle, jamming the driver who appeared to be dead. The autopsy report found severe and deep lacerations on the legs, body and head. Both legs and the right humerus were broken. Several ribs were also broken and one had pierced the heart. The stomach smelt strongly of alcohol. The cause of death was given as direct injury to the heart, combined with shock.

When Heather had read every page she folded them back into the plastic bag and said, ‘Right, let’s go’. I was quite surprised. It had taken an enormous amount of emotional energy to get us there and now she just wanted to leave. I had expected we would read over the documents again and possibly chat about some of the content, but Heather just wanted to go. I suggested we acquire a copy of what we had just read. She was disinclined. She did not see the need to have copies. I went to enquire how much the copies would cost. They were less than one dollar per page and PROV would post them to us. I ordered one set.

Once outside I felt drained but also slightly elated. We had managed to navigate this difficult emotional journey and had discovered so much more than we had imagined. The minute details contained in the Coroner’s Inquest provided a wealth of information. During the drive to our hotel we talked about other things and began to relax. A little later Heather said, ‘Now I know more than anyone else. Even Uncle Jock didn’t know there was an inquest. He said there wasn’t one’.[12]

Photograph courtesy of Heather McDonald.

Return to Abdullah Park

The following day we drove to Geelong for the next part of our expedition. Here we were keen to locate the numerous boarding houses Heather resided in as an orphan lodger. We had also arranged to visit Abdullah Park. Heather recalled a family story of how her father bought the property. Prior to the sale the surveyors calculated the land area as three acres less than the vendor Mrs Eleanor Gibb had indicated. Donald said he was not paying for land that was not there and Mrs Gibb would not change her price. A stand-off ensued, until Donald suggested they toss for it. The bank manager thought this was outrageous, declaring ‘You’re not tossing in my office!’, so they all went outside onto the pavement. Donald won the toss. He leased the 2500-acre wheat farm in Miram South and moved the family 400 kilometres to Abdullah Park. Eleven weeks later he was dead.

At the time, Heather knew her father had died in a car accident but it was not until she read the inquest documents that she discovered the details. With these precise particulars, and with Heather’s memories and the documents from the shoebox, we can now piece together how the accident occurred.

It was the evening of Thursday 9 September 1937. Donald had a business meeting at the Criterion Hotel in Geelong just seven kilometres from his new home at Moolap. When he failed to arrive home by sunset, Clara rang the hotel and was told that Donald had left half an hour earlier. Concerned, she kept ringing around to find out where Donald could be. Finally the police came over the telephone line. ‘There’s been a collision between a car and a tram on Ormond Road. It’s your husband Donald.’

A horse and dray with no light on the vehicle was on Donald’s side of the road.[13] He swerved his 1936 Ford to miss it, but, with only one eye, fading light, and rainy weather conditions he misjudged the distance and ran into a tram that had just left the East Geelong terminus on its way to town. He was killed instantly. That night Clara told the girls there had been an accident outside Mrs White’s house. It was their Dad, she said, and he was being looked after. The next morning the girls were told their father had died. It was Gwen’s fourteenth birthday. Clara was thirty-eight, Marjory was ten, and Heather had just turned seven.

Recently moved and suddenly without the head of the family, Clara and the girls continued to live at Abdullah Park. Then, unthinkably, less than four years later Clara was taken to the Geelong hospital suffering from an unknown illness. Critically sick for one month, she died in hospital leaving her three daughters orphaned.

Photograph by Janet Marles.

Two months later, on 10 August 1941, the girls packed up their belongings from Abdullah Park and moved into Geelong with a friend of their mother’s, Mrs Pearse. Heather continued to attend the local school along with the children of the family who moved into Abdullah Park, yet, as she recalls with some surprise, she never spoke to these children about Abdullah Park and never even enquired about the cats they had had to leave behind. Such was the all-pervading pressure not to speak of her ordeal.

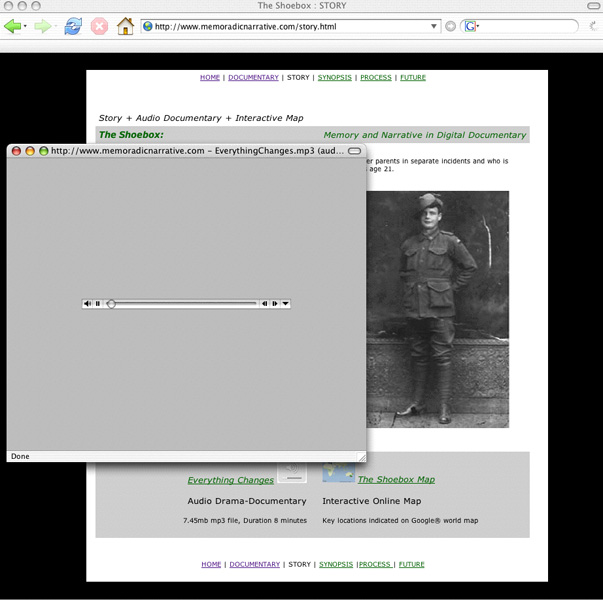

Everything Changes: An Audio Drama-Documentary

With this portion of our genealogical journey completed, Heather and I returned to our respective homes. I began collating the information, documents, newspaper reports, interviews, and photographs we had uncovered and started developing a script for an interactive online documentary of Heather’s unique story, called The shoebox.[14] It was clear Donald’s accident was crucial to the sequence of events and I decided to write this part of the story as an audio drama-documentary.[15]

Sound design is a central feature of online documentary production and I wanted to explore this re-enactment as audio only, allowing the audience to picture the scenes with their individual mind’s eye. I gave this sequence the title Everything changes. It consists of nine scenes and is termed a drama-documentary because it is a dramatisation of reality. As Cohen et al. state, ‘this genre of documentary blends drama and fact with dramatic stories – involving either real persons, or actors confronting real issues – presented as being true’.[16]

Everything changes describes Heather’s family’s relocation from the Wimmera to Abdullah Park in Moolap in July 1937 and Donald’s fatal car accident eleven weeks later.

Image by Janet Marles.

Conclusion

Like detectives, historians and documentary-makers need to find the evidence – the piece of paper, the record, the statement, or photograph – that can verify the story they are building. These, sometimes tiny, pieces come together to provide texture, depth, and clarity to the narrative content. The act of uncovering these portions can in turn be surprising, tedious, fascinating, traumatic and cathartic. I have experienced all of these sensations as I sifted through various databases and archives searching for historical records and accumulating the numerous fragments of evidence to piece together my mother’s life story – a story that began to emerge with the discovery of a shoebox and expanded with archival research into a website and audio drama-documentary.

Endnotes

[1] Interview with Heather recorded 2005.

[2] Interview with Heather recorded 2005 and confirmed in my meeting with Grahame McDonald and his mother on a trip to the Wimmera in November 2005.

[3] Conversation between Grahame McDonald and the author in November 2005.

[4] M Gibson, Objects of the dead, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2008, pp. 47-79.

[5] Copies of the Geelong advertiser for 1937-1941 were examined in the Geelong Historical Society Newspaper Archives in November 2005.

[6] Geelong advertiser, Saturday 10 and Sunday 11 September 1937.

[7] Interview with Heather recorded 2005.

[8] A Haebich, ‘A long way back: reflections of a genealogical tourist’, Griffith Review, 6, 2004, p. 181.

[9] A draped urn often symbolises the death of an older person: see, for example, the Art of Mourning website, available at <http://artofmourning.com/symbolism.html>, accessed 22 October 2010. John McDonald died in 1922 at the age 73, Mary died aged 77.

[10] PROV, VPRS 24/P Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 1339, File 1937/1288.

[11] This statement is corroborated in the the Geelong Mechanics’ Institute meteorological station registrations reported in the Geelong advertiser: rain (from 6 pm) to 9 am (night of 9/10 September) – 34 points.

[12] Interview with Heather recorded 2005.

[13] PROV, VPRS 24/P, Unit 1339, File 1937/1288, pp. 7, 8.

[14] J Marles, The shoebox: memory and narrative in digital documentary, containing a Synopsis, available at <http://www.memoradicnarrative.com.story.html>, accessed 22 October 2010, and a Documentary, available at <http://www.memoradicnarrative.com/doco.html>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[15] Everything changes can be accessed online as an MP3 audio file, available at <http://www.memoradicnarrative.com/Clips/EverythingChanges.mp3>, accessed 22 October 2010.

[16] H Cohen, JF Salazar & I Barkat, Screen media arts: an introduction to concepts and practices, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2009, p. 304.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples