Last updated:

‘The black sheep: Robert Herdman of Paisley, Scotland and Australia’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Marilyn Kenny and Anne Herdman Martin.

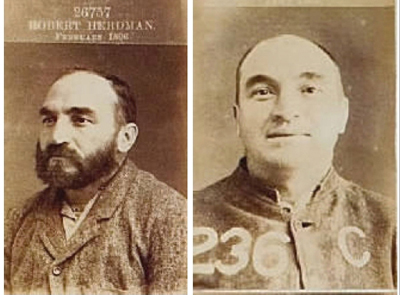

Family historians often come up against brick walls in the shape of lost family members. In 2007, British family researcher, Anne Martin, challenged herself to find her great-uncle, Robert Herdman. Born in Scotland in 1861, Robert had gone to sea and no word of his destiny had reached the family. Fortunately, this lost sheep was also a black sheep and left traces of his activities in government records now held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV). By using, firstly, a general family search list, Anne made contact with local researcher, Marilyn Kenny, who was able to elicit from PROV records that Robert had a criminal record. From that beginning, and using a variety of online sources, Anne and Marilyn were able to track Robert’s life journey from the time he left Scotland in 1891 as a shilling-a-month man working his passage to Australia. Robert, a baker by trade, travelled around south eastern Australia working as a shearers’ cook. On at least two occasions, he was before the court and served a sentence at HM Gaol Pentridge. Marilyn Kenny sourced Robert’s prison photograph from PROV records and provided family members with their first sight of the lost sheep in over 100 years. Robert became a patient of Dr John Elder Butchart at the Austin Hospital and died there in 1914. The research demonstrates how much, and how varied, is the social and individual information available in public records.

Family historians frequently encounter lost ancestors, those who have dropped off the family tree. The Herdman family of Paisley had such a son, whose fate was still puzzled over more than one hundred years after he was last seen in Scotland. Fortunately this lost sheep was also a black sheep and so left traces of his doings in government records now held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).

In 2007 British family researcher Anne Martin, née Herdman, decided to try locating her great-uncle Robert Herdman, who was born on 18 February 1861 in Paisley. Robert Herdman was the second, but oldest surviving, son of Robert Herdman and Isabella Lockhart (1854–82). The Herdmans had been Paisley folk since 1801 and counted amongst their number a bagpipe reed maker and a silk shawl weaver. ‘Old’ Robert Herdman, born in 1829, made good as a baker and businessman. After training and working as a journeyman, he became a master baker and moved to Saltcoats to work at the bakery and granary, which he bought in 1875. Robert was a highly competent baker and a shrewd businessman. He built a quality bakery and tearoom business that was run successfully by his descendants until 1968.[1]

Old Robert was a respected member of Trinity United Presbyterian church and had such a good relationship with the Minister, George Philp, that he named one of his daughters after him and appointed the Minister as one of the trustees of his will. Robert and Isabella had eight children, four of whom, including young Robert, trained as bakers. Other daughters worked in the baker’s shop and tearooms. Young Robert shows up in the 1881 British census working as a baker in his father’s business. The next year his mother Isabella died an untimely death and Robert then seems to disappear from local records.

No detail about his fate had been passed down except that he was lost, perhaps ‘gone to sea’. Anne looked at all types of records in her efforts to find young Robert, with nil return. She then did what many searchers do: she googled the name. Amongst the 1,440 hits was one from the Index to Missing People found in Victoria Police correspondence records.[2] This indicated that solicitor James Campbell of Saltcoats, Scotland was seeking Robert to convey to him his share in Mr Herdman’s estate. Anne then posted a query on a Victorian mailing list with a family history focus. Several responses offered leads and amongst these was one that looked promising. This was for a Robert Herdman, born 1861 in Scotland, listed in the Victorian Prisoners’ Index.[3] Reference to the relevant volume in the Registers of Personal Descriptions of Prisoners[4] was critical in establishing that this was indeed her great-uncle.

The record stated that this man had arrived in Victoria in 1892 per the Loch Catherine. No such ship showed up in the PROV Index to Inward Passengers.[5] However, Nicholson’s Log of Logs[6] indicated the existence of a Loch Katrine, which was listed as arriving in Melbourne in February 1892. Robert’s name was not amongst the seven passengers, but Campbell’s letter had said that Robert was known to be a ship’s steward so it was possible that he had arrived as a member of the crew. The Loch Katrine was part of the Glasgow, Loch Line. Aitken, Lilburn &. Co.[7] began operating a line of ironclad clipper sailing ships to Australia in 1870. The usual course was to take on cargo and passengers at Glasgow and then sail to Adelaide. In Melbourne or Sydney wool or grain was loaded and routed to London.

The company never changed to steamships but persisted with sail.[8] Passengers, however, preferred the speed and comfort of steamers and freight rates dropped. The ships usually managed one round voyage to Australia per year and half of this time was unprofitably spent in port. The Loch Line had the reputation of being unlucky, as eighteen vessels out of the fleet of twenty-five were wrecked, went missing, sank in collisions, were destroyed by fire or were the casualty of wars. The Loch Katrine was built in 1869 and was a three-masted, 1,252 tonne ship. Robert certainly found the ship unlucky as he later complained of memory loss caused by head injuries sustained when a ship’s block fell on his head.[9]

Anne obtained the Agreement and Account of Ship’s Crew for this voyage of the Loch Katrine.[10] This recorded that Robert had signed ship’s articles in November 1891 in Glasgow. He was one of a crew of twenty who agreed to conduct themselves in an orderly, faithful, honest and sober manner, be diligent in their duties, accept the scale of provisions [no spirits allowed] and use only safety matches on board. Robert claimed to have been previously a crew member on the SS Warwick, a 400 passenger vessel on the United Kingdom to North America run. The crew of the Loch Katrine signed on for an expected voyage of two years’ duration. Robert, however, made a mutual agreement with the Master to be discharged in Melbourne. He was paid only a shilling a month for his work as an assistant cook so this was the equivalent of working his passage. The ship departed November 1891 on its twenty-sixth trip with a cargo of iron for its 106-day voyage to Melbourne, arriving 21 February 1892. At the Mercantile Marine Office Robert received his wages and was discharged. His discharge certificate shows that Robert received a ‘very good’ stamp for ability and conduct.[11]

Anne and Marilyn could not find any records relating to Robert’s movements until he is reported in 1894 at Deniliquin in New South Wales. On 1 September 1894 Robert was involved in the Wanganella riot, one of many civil disturbances in the 1894 Shearers’ Strike. This dispute was one of Australia’s most violent industrial conflicts. The Pastoralists Association attempted to cut pay and conditions and employ free or non-union labour and was strongly resisted by the Australian Workers’ Union representing the shearers.[12] As reported in the Pastoral Times[13] a party of non-union labour proceeded through Deniliquin bound for Wanganella Station. A band of thirty unionists on horseback shepherded the convoy ‘howling and threatening’. The Billabong Bridge was blockaded and unionists surrounded the strikebreakers, waving sheets of iron, trying to stampede the horses. The animals drawing the vehicles bolted, drays overturned and were smashed. The riot was quelled by a magistrate armed with a revolver who threatened to shoot anyone who impeded the police trying to open a passage on the bridge. The newspaper states that at the height of the tumult police took special notice of the conduct of several men who played a prominent part in the disturbance. Later that night police with warrants came into the shearers’ camp and arrested three men, one of whom was Robert Herdman.

The first trial ended with his acquittal on a technical point. He was then re-arrested, charged with riot or tumultuous assembly and affray, and committed for trial by a higher court.[14] Robert was bailed with two sureties of £40 and stood trial at the Sessions Court on 5 October. The plea was not guilty.[15] His evidence was that he was a baker and shearers’ cook and had left the camp with all the union shearers. The shearers had gone to blockade the bridge and deter the convoy of non-union labour. Robert however had gone first to the hotel, then down to observe the action. At the bridge he had invited one of the non-union men in the coach to come back to the hotel with him, which he had done. Herdman denied creating a disturbance and the man who went to the hotel with him testified that he was not frightened. The jury after deliberating from 6.30 pm to 8.40 pm delivered a not guilty verdict.

A week later on 12 October 1894[16] Robert arrived in Echuca with a gang of men travelling on the train from Deniliquin. They alighted to wait for the Bendigo train. Herdman asked one of the passengers, John White, whether he would shout drinks. White was then enticed to leave the railway station bar and come for a drink at another hotel in the town. Several witnesses stated that they observed Herdman trying to remove items from White’s pocket and roughing him up. White blacked out and when he came to he found his cash, pay cheques and personal items were missing. He went to the police station and it was while he was later searching the town with a constable that he came across Robert, who had been taken in charge, arrested for drunkenness in yet another of the town’s hotels. There were reports from several of the town publicans that Robert had been one of the men trying to cash White’s pay cheques. Robert was charged with feloniously taking and carrying away cheques to the value of £28, and £42 in cash and a number of other articles.[17] Robert stood trial before Judge Arthur Wolfe Chomley (1837–1914) at the Circuit Echuca General Sessions Court on 8 November. Chomley had been assistant Crown Prosecutor in the trial of Ned Kelly in 1880.

Robert was defended but his barrister was unsuccessful in the application that the £1 7s 6d found on Robert be handed over to assist with his defence. The prosecutor stated the £1 was part of the stolen goods. Robert could not give a clear account of events. He explained that while working on board ship a block had fallen on his skull and a drink or two caused him to lose his memory. He had been working but after getting his cheque had ‘scattered it broadcast’ and it was ‘hard to say what had become of it’. In his defence Robert seemed to indicate that others were involved but was unable to produce witnesses, ‘being but newly arrived’. The newspapers[18] reported that Judge Chomley ‘summed up greatly against the prisoner’ and the jury after a short retirement returned a guilty verdict. Robert was convicted of ‘larceny from the person’. He was sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour and transferred to the Bendigo Gaol and then Pentridge.

In the register of persons received as prisoners at Pentridge he is described as five feet five inches in height, with a stout build, 12 stone 12 lb in weight, a ruddy complexion and a round visage. He had hazel eyes and medium features; his dark brown hair was receding from his forehead. A scar on his forehead perhaps confirms his story of an accident at sea. The record gives his native place as Glasgow, his religion as Wesleyan and trade as baker. He was able to both read and write. His description highlights his previous maritime background, as under distinguishing marks he was noted to have tattoos of a tombstone engraved with ‘In memory of my mother’ on his right arm, a sailor on his lower right arm, a star on his right hand, a heart, cross and anchor and wreath on his left arm and an anchor on his left hand. His conduct in prison was described as only fair, and by committing three offences whilst in prison, including the use of improper language, he experienced a total of five days’ solitary confinement. He served the full term and was released on 7 March 1896.[19]

Herdman’s name appears on the 1903 Federal electoral rolls as a cook on a station ‘Ennerdale’ at Darlington in the Western District. There seems to have been frequent turnover of the staff employed there by the grazier, but Robert Herdman’s name is constant over the period 1903–1909. After this time he takes up the itinerant life that would have been common to many working men of the period. This lifestyle is detailed in records that date from September 1913.

When James Campbell wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Police in September 1913 he explained that he had attempted to trace Robert in 1910.[20] Robert’s father died in 1886, gifting the bakery business in its entirety to his eldest daughter Jeanie. This was an unusual move which may be linked to young Robert’s alienation from the family. Old Robert’s personal estate of £1260[21] was to be divided among his children. The family had not heard from young Robert but had managed to track his discharge from the Loch Katrine in Melbourne. In 1910 the siblings applied to the Ayrshire Sheriff’s Court for an ‘assumed dead’ judgement and for Robert’s share in the estate to be distributed. The sheriff ordered that a search be made for Robert. An advertisement in the Argus resulted in a letter from Victoria indicating that Robert was working on a property at Woorndoo near Hamilton. Campbell had, however, come to a dead end in following this up.

Three years later, the siblings re-approached the Sheriff’s Court but were again ordered to advertise in Victoria and New South Wales. This advertisement resulted in a letter from the manager of ‘Warrowe’, Irrewarra near Colac. He wrote that from 1 March to 24 June 1912 Herdman had been working there as a cook /baker at a rate of 25 shillings, plus keep, per week. He enclosed a copy of an agreement between Robert and the owner Charles Lamond Forrest, MLC. Campbell as solicitor for the trustees then wrote to the Chief Commissioner in Melbourne requesting assistance. A ‘missing friend’ inquiry was put in place by Victoria Police. The police correspondence file indicates that from November 1913 to January 1914 police from four different districts instituted thorough inquiries. The matter was advertised in the Police Gazette[22] where it was noted that ‘a legacy awaits him in Scotland’.

The police at Beac interviewed the manager of ‘Warrowe’ and also a man who was supposed to have been on a train with Herdman in December 1912. However, this man was not acquainted with Herdman and was not sure whether it was him! The information obtained pointed to the Koroit district. Police there could find no current trace but they were informed that Herdman had been at Mundiwa Station near Deniliquin. He was reported to be in bad health and in October 1913 a mate had left him in Melbourne where he was attending one of the city hospitals. Robert then planned to go on to Mount Violet. When in Melbourne he normally stayed at Mr Watts’s Antonio’s Hotel. At this point Constable No. 4274 Thomas Henry Haigh at Bourke Street West police station took up the case. Haigh (1862–1928) had joined the force in 1890[23] and was to prove most persistent with this inquiry. He established that Herdman was very well known at Antonio’s Hotel at 444 Flinders Street, his usual haunt whenever he came to town with a few pounds. Herdman was known as Scotty Bob, Aberdeen Lad or Ayrshire Lad and ‘spoke very Scotch’. Before leaving Melbourne in October 1913 Robert had had an operation performed on him at the Melbourne Hospital.

The file was transferred but Colac police could find no trace of Robert at Mount Violet, nor had he been treated at Colac Hospital. The file returned to Melbourne where Constable Haigh referred it to Ballarat police so that they could make enquiries of the Australian Workers’ Union. It was assumed that Herdman would have a union ticket and could be traced by that means. However, the name of the missing friend did not appear on the union rolls for Victoria and Herdman had not been treated by the Ballarat Hospital. By late January the Chief Commissioner was asking for a progress report on the matter. Constable Haigh was confident that Herdman would come to the hotel ‘any day and I am sure I will trace him before long’, but he suggested an advertisement in The Worker, a paper circulated amongst labouring men in town and country. On 6 February 1914 Haigh reported that ‘I have traced Robert Herdman. He is staying at Antonio’s Hotel, his fixed address. On being shown the [Mr Campbell’s letter he placed his affairs in the hands of Mr Evans and Masters, Queen St Melbourne.’

James Campbell was so informed by the Chief Commissioner. By 23 March Campbell was writing that he had heard from the Melbourne solicitors and offered to pay for any outlays in connection with the enquiries. Robert would have received at least £180 from the estate. This probably was used to make his last months comfortable for he had been diagnosed with cancer in August 1913. The Austin Hospital reports[24] show that Robert was admitted on 15 July 1914. At this time the Austin Hospital was for ‘incurables’, and was the only hospital to admit this category of patients. The medical superintendent Dr John Elder Butchart (1867–1927) examined applicants for admission each week at the Melbourne Hospital or visited them at home if they were bedridden.[25] There were at this time 214 patients at the Austin and Robert was one of 11 new patients who were admitted in that fortnight. Some of the Herdman legacy may have gone towards hospital expenses. At this time those patients who had means did pay fees. In the year 1914 patients contributed £917 to the hospital costs of £19,373.[26] The superintendent’s fortnightly report[27] indicates that Robert Herdman died on 18 October 1914, one of eight deaths in that period. He was buried in a private plot in the Presbyterian section of Pine Ridge Cemetery, Coburg.

Marion Button’s index indicated that there were two photographs of Robert Herdman included in the Central Register of Male Prisoners.[28] However at the time this research was being done this record was unavailable for ordering. Pam Sheers at PROV advised that this volume was being digitised and that it was only a matter of time before it could be accessed. A few months later the PROV newsletter announced that this volume was now online. Robert Herdman’s family were finally able to be re-united with him across time and hemispheres and could gaze at their black sheep. Bad Uncle Bob has used his time in gaol to grow his beard!

Endnotes

[1] The information in the foregoing paragraph is based on the recollections of Robert Herdman’s great-niece, Anne Herdman Martin. Anne was born in 1943 and until 1952 lived in the family bakery in Dockhead Street, Saltcoats. She now lives in Yorkshire, England. Oral family history and several photographs were passed down to her by Robert Herdman’s sister-in-law (Annie Crawford Currie Herdman, 1888–1962) and by his younger sister (Isabella Lockhart Herdman Baillie, 1871–1960). Following the death of her parents, the bakery business passed to Anne and her brother, Douglas. Anne’s second source of oral family history and photographs, Isabella Herdman (Aunt Belle), lived in the neighbouring town of Ardrossan, Ayrshire.

[2] A sequence of correspondence dating from 1912 to 1914 regarding Robert Herdman’s whereabouts can be found in PROV, VA 724 Victoria Police, VPRS 807/P0, Inward Correspondence Files, Unit 1297, File number O 11801. The index to missing persons was compiled by Helen Harris OAM, and is available online at <http://members.ozemail.com.au/~hdharris/>, accessed 30 August 2009.

[3] Marion Button (comp.), Victorian Prisoners’ Index 1850-1900 (Males), M Button, Gisborne, Vic., 1995, provides access details to a number of Victorian Public Record Series relating to male prisoners.

[4] PROV, VPRS 10858/P0, Registers of Personal Descriptions of Prisoners Received, Unit 9, Folio 964, Prisoner Number 26757.

[5] PROV Index to Unassisted Inward Passenger Lists to Victoria 1852-1923, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/unassisted-passenger-lists>, accessed 26 March 2020.

[6] Ian Nicholson, Log of logs: a catalogue of logs, journals, shipboard diaries, letters, and all forms of voyage narratives, 1788 to 1988, for Australia and New Zealand and surrounding oceans, Yaroomba, Qld, the author jointly with the Australian Association for Maritime History, 1990-98. A copy of this and many of the other publications cited in this article are held in the Victorian Archives Centre reading room library.

[7] The Ships List website <http://www.theshipslist.com/>, accessed 30 August 2009.

[8] The Loch Line of Glasgow website <http://www.thelochlong.info/Aitkenlilburn.htm>, accessed 30 August 2009.

[9] These events were recalled by Anne Herdman Martin – see note 1 above.

[10] Crew Agreement Index, Maritime History Archive, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John’s, Canada, available online at <http://www.mun.ca/mha/holdings/searchcombinedcrews.php>, accessed 30 August 2009.

[11] PROV, VA 606 Department of Trade and Customs, VPRS 558/P0, Seamen’s Discharge Certificates (Mercantile Marine Office), Unit 19, Book 213.

[12] Banjo Paterson composed ‘Waltzing Matilda’ in January 1895 when he was staying on a Queensland property where, in September 1894, a woolshed had been burnt down during the strike, and a shearer died.

[13] Pastoral Times, 8 September 1894, The Shearing Troubles.

[14] Pastoral Times, 15 September 1894, Deniliquin Police Court.

[15] Pastoral Times, 6 October 1894, Deniliquin Circuit Court.

[16] Echuca and Moama Advertiser, 10 November 1894, General Sessions. A microfilm copy of this newspaper is available at the State Library of Victoria.

[17] Echuca and Moama Advertiser, 8 November 1894, General Sessions.

[18] Unfortunately the brief relating to Robert’s trial in Victoria does not appear to be in PROV custody. Records created by the Echuca Courts, PROV, VPRS 3018/P0, Judges Note Books, Unit 16, or PROV, VPRS 3016/P1, Verdict Books, Unit 1, do not provide any details regarding the case.

[19] PROV, VPRS 10858/P0 Registers of Personal Descriptions of Prisoners Received, Unit 9, Folio 964, Prisoner Number 26757.

[20] James Campbell, Ayrshire, Scotland, to the Chief of Police, Melbourne, Australia, dated 25 September 1913, PROV, VPRS 807/P0, Unit 1297, File number O 11801.

[21] Herdman Robert 29/01/1887 Baker, Saltcoats, d. 17/05/1886 at Saltcoats, testate Ayr Sheriff Court Wills SC6/46/18. Herdman Robert 31/01/1887 Baker, Saltcoats, d. 17/05/1886 at Saltcoats, testate Ayr Sheriff Court Inventories SC6/44/48. Located through Scotland’s People website at <http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/search/SearchResults.aspx>, accessed 30 August 2009.

[22] Victoria Police Gazette, no. 52, 24 December 1913, p. 646.

[23] Index to Members of the Victorian Police 1853-1953, Victoria Police Historical Society, Melbourne, 199-.

[24] PROV, VPRS 609/P0 Reports [Austin Hospital], Volume 3, Resident Medical Officer Reports, p. 223.

[25] EW Gault and Alan Lucas, A century of compassion a history of the Austin Hospital, MacMillan, South Melbourne, 1982, p. 350.

[26] AM Laughton (Victorian Government Statist), Victorian Year Book 1914–1915, no. 35, Government Printer, Melbourne, p. 559.

[27] PROV, VPRS 609/P0 Reports [Austin Hospital], Volume 3, Resident Medical Officer Reports, p. 237.

[28] PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 515/P0 Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 48, Folio 464, Prisoner Number 26757. An online copy of Robert Herdman’s page in the prison register can be viewed at <http://access.prov.vic.gov.au/public/veo-download?objectId=090fe273813070a6&format=pdf&docTitle=HerdmanRobertNo26757&encodingId=Revision-2-Document-1-Encoding-1-DocumentData>, accessed 26 March 2020.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples