Last updated:

‘“Give to us the People we would Love to be amongst us”: The Aboriginal Campaign against Caroline Bulmer's Eviction from Lake Tyers Aboriginal Station, 1913-14’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 7, 2008. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Victoria Haskins.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Between 1913 and 1914 the residents of the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Station waged a campaign to allow Caroline Bulmer, the widow of their late missionary, to remain on the station with them. Preparing two separate petitions, the first to the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines, and the second to the Governor of Victoria, the residents sought to make themselves ‘understood’, as they put it, to the authorities at a time of great uncertainty about their future. This was a critical moment in the history of Aboriginal administration in Victoria, as the State garnered increasing and encompassing powers to control Aboriginal people and their land. Mrs Bulmer’s continued residence was vehemently opposed by the Board’s appointed manager of the reserve, and his hostility to the widow can tell us something about the lives of those who were forced to live under his administration. While the petitioners were unsuccessful, the story of their campaign, buried in the PROV archives, brings to light a forgotten, and perhaps unexpected, episode of cross-cultural collaboration on the issue of land and policy. Drawing on recent scholarship on the Indigenous use of writing as a tool of resistance, this article highlights the complexity of relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and reveals the persistence of Aboriginal efforts to determine their own future and to assert their right to do so.

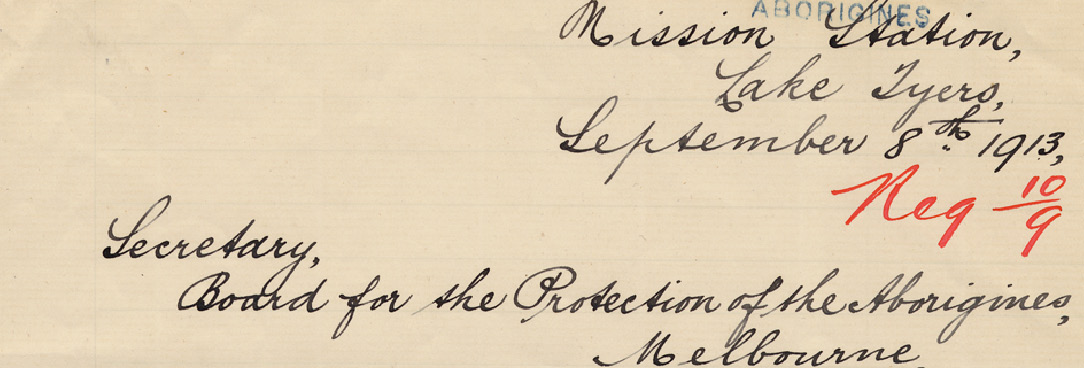

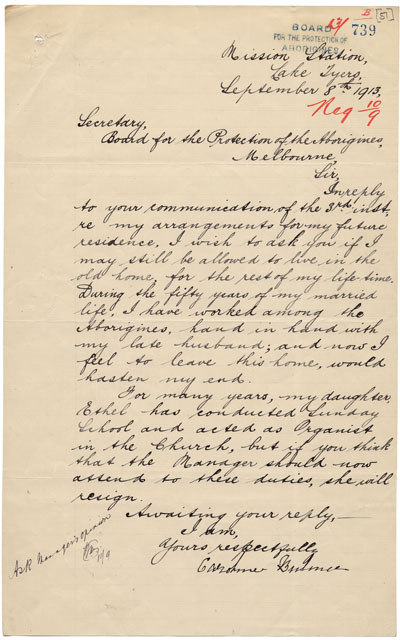

In September 1913 Caroline Bulmer, widow of the missionary John Bulmer, wrote to the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines to request that she ‘be allowed to live in the old home’ she had shared with her late husband on Lake Tyers Aboriginal Station ‘for the rest of my life-time’, adding that ‘I feel to leave this home, would hasten my end’.[1] She had just received Board advice that she and her dependent adult daughter Ethel were obliged to leave the station. It was a pathetic case: her husband had died barely a month earlier, she was 73 years of age, and she had known no other home since the start of her married life fifty-one years previously. The Aborigines Act 1886, under which no Aboriginal person of mixed descent under the age of 34 was entitled to reside on an Aboriginal station, was in full force, but Mrs Bulmer’s situation as an elderly white woman was unique. Intriguingly, the Aboriginal residents of the station strongly supported her cause. Having already spelt out their concerns on her behalf in a carefully written petition to the Board, they prepared a second to be presented to the Governor of Victoria. The first of these petitions lies alongside Mrs Bulmer’s letter and further correspondence and documents in files held at PROV. The second petition, apparently never delivered to the Governor, is in another, rather slimmer file, also in the PROV archival collection.[2]

In the end the campaign for Mrs Bulmer’s tenure was unsuccessful. It is one of those forgotten snippets of the past that lie buried in the archives of Aboriginal administrations around Australia – another small, lost cause all but discarded from historical memory. But the story of the Aboriginal campaign against Mrs Bulmer’s eviction rewards closer examination, though it is one we might struggle to interpret. It will, perhaps, surprise the present-day reader to find a white woman of that time pleading with the authorities to be allowed to live amongst Aboriginal people on an Aboriginal reserve; we might find it even more curious today that the Aboriginal residents should have merged their own struggles with her cause. Certainly the petitions highlight a complex episode of alliance between a white woman and an Aboriginal community that interrupts a history dominated by representations of female and Aboriginal passivity and submission. More crucially, however, the story provides an insight into the fissures within the edifice of a white colonising power, so often imagined to be monolithic and unfaltering, revealing some of the ways in which those on the receiving end of colonisation resisted by intervening and actively engaging at such interstitial moments.

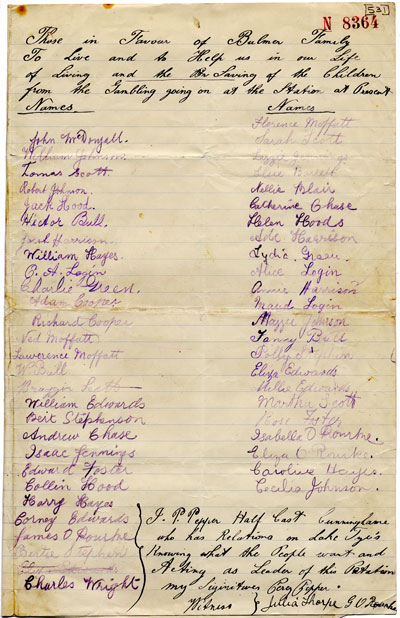

A simple narrative can be constructed from the archives. Such a narrative opens with the first petition, bearing 42 names, being received by the Board in August 1913 just five days after John Bulmer’s death. The Board thereupon sent a remarkably distant letter to Mrs Bulmer, advising her that ‘under the altered conditions your claim to occupy the quarters at the Aboriginal Station has ceased’.[3] Mrs Bulmer replied to ask – with what seems a certain degree of confidence – that she be permitted to stay. Promptly approached by the Board for his ‘opinion’ in the matter, the manager RW Howe made his hostility to Mrs Bulmer explicit, by which time – late September – the existence of the second petition had come to the Board’s attention. In November 1913 the Board notified the widow that it could ‘not approve’ of her remaining at the station after the end of that year. As events transpired, her date of removal would be deferred in late December till the end of January 1914, and then again till the end of March, and in fact it was not until May 1914 that the Board’s vice-chairman himself informed Mrs Bulmer that she was required to ‘remove with as little delay as possible’, and to ensure she had ‘severed her connection with the station by the end of June’. ‘[S]o far as the Board [was] concerned’, the decision was ‘final’, he stated firmly. Yet the Board was finally obliged to provide an annual pension, conditional upon Mrs Bulmer vacating the station, to persuade her to leave – which she did, on the very last day of June 1914.

Nobody who looks through the records of the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines can fail to be struck by the prevalence of ‘the Aboriginal voice’ within their pages: the Indigenous communities of Victoria reveal themselves to be prolific letter-writers who were more than willing and able to adopt the constitutional tools and methods – including formal petitions – of white Victorians to defend their interests.[4] In her perceptive discussion of Aboriginal writings from Lake Condah in the same time period (and in the same archive), Penny van Toorn reminds us that these carefully worded public texts, seemingly concessionary and couched in the language of the white oppressors, can carry embedded within them ‘hidden transcripts’ of resistance, and evidence of chronic dissatisfaction.[5] At the same time, the Aboriginal petitioners themselves seem intensely aware that they are writing to a particularly obtuse audience – white, educated, male authorities – to whom they wish to make their point unambiguously. ‘We will try to make ourselves understood’, the first petition begins. ‘It is on behalf of Mrs Bulmer & Miss Ethel Bulmer that we are concerned about.’

Aged about 21 when she married widower John Bulmer in January 1862, Caroline had accompanied her husband later that year to set up home on the site he had only just selected for a new Church of England mission in Gippsland, at Lake Tyers.[6] Decades later, in mid-1907, the Board, which had been pushing for the closure of one or more of the Aboriginal missions since the turn of the century, resolved to take over the management of Lake Tyers Station and oversee the transfer there of Ramahyuck Mission residents, appointing RW Howe as manager.[7] Bulmer had asked permission to remain in his house with his wife and ‘minister to the spiritual needs of the Aborigines’. The Board consented, and allowed him, his wife and daughter to continue to receive rations.[8] But the Bulmers only remained on sufferance, and when John Bulmer died his aged widow was entirely redundant. ‘As her role was created by marriage, so it was destroyed by her husband’s death’, observes historian Hilary Carey of the missionary wife’s experience in the Australian colonies.[9] For the Lake Tyers people, preparing their petition within a few days of John Bulmer’s death, the uncertainty of his widow’s position was likely to have been a source of cultural anxiety as well as symbolic of their own insecure position. John Bulmer had earlier recorded the care that ‘the Gippslanders’ had shown a bereaved widow, noting also their belief that when a man died his spirit ‘may hang around the camp for a time to see to the interests of his wife, but as soon as all is settled he takes his departure’, as told in the story of a ghost who haunted his wife until the people organised her remarriage.[10] What the residents of Lake Tyers made of Caroline Bulmer’s situation in spiritual terms we cannot know, but we can be sure they would have felt it appropriate, even urgent, that someone look after her interests. They had reportedly been very concerned about what would become of John Bulmer back in 1907, and a sense of their loyalty to his memory – rather than a concern for Caroline Bulmer’s welfare per se – comes through strongly in their advocacy for his widow in the first petition. Reverend Bulmer had ‘spent his life time amongst us’ this petition stressed, and through his teachings and the ‘home’ he established at Lake Tyers, ‘many were led to lead better lives’. He was

our beloved minister, friend, adviser, & father … and we now miss his familiar face among us. For over (50) fifty years he laboured among the natives, and we will probably never get another to spend a life of self-sacrifice as he did.

The petitioners asked only that ‘if she wishes’, Mrs Bulmer be allowed to stay at the station, without making any specific claim for her. However, they went on to request that her daughter Ethel be allowed ‘to live with her & carry on the work in which she assisted her late father’ (conducting Sunday School) and pointed out that ‘Yesterday Sunday there was neither Sunday school or Church, and if this is what is before us, then it is a poor outlook for the children & younger ones growing up’. Two of the Bulmers’ adult children resided on the station at that time. Son Frank, who John had once hoped would take over from him as manager, was on a salary as an assistant to Howe,[11] while Ethel, who had earlier returned to Lake Tyers to act as matron there until Howe’s wife could take up that duty, was now taking Sunday School and playing the church organ in return for her rations.[12] The reference to Ethel’s contribution could be read as a pointed criticism of the government’s administration of the station.

The Board it seems did not deign to reply. Whether its members recognised the implicit challenge in the petitioners’ statement of their own perceived obligations to the late missionary, or were annoyed by the aspersions cast on their secular management, or were simply being bloody-minded, the decision to evict Caroline Bulmer was made in direct response to the petition. A minute scrawled on the back of the document a fortnight later (1 September) by secretary Ditchburn would be repeated in the blunt note sent to her two days later: ‘Write Mrs Bulmer pointing out that she has now no claim to occupy the quarters inquiring what arrangements she proposes to make her future residence’. So it was, in fact, the intercession of the Lake Tyers people on behalf of Mrs Bulmer that was the catalyst for the Board’s decision to evict her.

In her initial response to the Board’s letter, Caroline Bulmer had also insinuated the spiritual inadequacy of government administration when she suggested, somewhat slyly, that if the Board thought Howe should take over her daughter Ethel’s duties Ethel would resign. However, over the following months her correspondence with the Board tended to argue her claim upon the house at Lake Tyers in financial terms alone, deviating from the need expressed by the petitioners for a continued church presence. Her home, she reiterated, was ‘wholly built by my late husband’ with the ‘assistance of the natives – thereby costing the Government nothing’. As a strategic device this may have seemed astute, given that the Board was always attentive to cost-saving measures, as Mrs Bulmer was well aware, but in fact it provided leverage for the Board. At the end of 1913 they offered to consider ‘a money allowance’ both as an inducement to Mrs Bulmer to leave and as a way of avoiding ‘the appearance of harshness’, eventually providing a pension of £52 per annum. The minutes of the Board’s discussion on this payment in 1914 show further that they were aware they were getting off lightly (compared with the monies provided to former male manager-missionaries on other stations), and, as her allowance was to be paid out of the ‘Compassionate Allowance Vote’ rather than their own coffers, in effect they had saved the cost of the rations allowed her on the station. These rations were, they noted, of equivalence. For Caroline Bulmer’s part, the financial hardship was probably less critical than the distress caused by leaving the home she had lived in all her married life and called her own. She had relations in the vicinity, and a male relative – possibly another son, an apparently successful timber merchant – took her in after she left the station and continued to represent her interests up until her death some five years later.[13] John Bulmer had left a modest estate of a little land and a house in Cunninghame let for 10s. a week; and in the event, if we can believe the spiteful report submitted by Howe soon after her departure, Mrs Bulmer was in a position to buy a block of land in Cunninghame and build a house on it.[14] Indeed she seems to have accepted the offer of a pension only once she was resigned to the inevitability of her eviction, ten days before she actually left.

We have seen that the Board’s initial decision to expel Mrs Bulmer was made in reaction to the petition from Lake Tyers. Their determination to carry this decision through would be based on the threat they were increasingly convinced her presence posed to the station management. On 16 September 1913, Howe had responded with irritation to the Board’s request for his opinion on Mrs Bulmer’s appeal. He complained that ‘the proposition was unworkable’, referring to the ‘party interests’ on the station and the need for the Board’s representative to have ‘sole and uninterrupted control over the natives’, as the ‘old regime [was to] be ended forever by the death of Mr Bulmer’. The Board asked him to elaborate.

It was clear Howe had been looking forward to directing Mrs Bulmer to go. Seeing his opportunity to do so evaporating, he was strenuous in his defence of his opinion. As he explained in his cramped writing: ‘What I meant by party interests, was that, at any time when I had occasion to correct or punish any of the blacks or halfcastes for misbehaviour’ (for example, sending people off the station), Mrs Bulmer would sympathise with those people, saying ‘that it was a shame to treat them like that’, and so ‘always caus[ing] a strong current of opposition against me’ and making ‘it much more difficult for my wife & myself to control the natives & maintain discipline on the Station’. Furthermore, he complained, Mrs Bulmer was in a habit of ‘order[ing]’ the people to carry out work for her ‘& they of course would not refuse her’, thus keeping them ‘from doing the work which I had instructed them to do’. All this meant that Howe ‘could not cope with the position without a great deal of unpleasantness which I wished to avoid during the lifetime of Mr Bulmer as he had nothing to do with the before mentioned facts’.[15]

Howe was known as ‘a hard man’ by the Lake Tyers people and his reputation lives on in their history.[16] In the archival records, his vindictiveness towards Mrs Bulmer betrays a man who felt his own position of authority to be insecure. A confrontation in 1911 between him and his wife and an Aboriginal woman, Emily Stephen, who had been moved onto Lake Tyers from Ramahyuck, provides a telling glimpse into the history of his relationships not just with the Aboriginal residents but also with Mrs Bulmer. It suggests too that the Aboriginal people were adopting a protective stance towards Caroline Bulmer even before her bereavement. Emily Stephen had arranged for her 14-year-old daughter to work for Mrs Bulmer (as a servant) and was incensed when Mrs Howe tried to bully the girl back to work in her own household, complaining to the Board of the Howes’s high-handed treatment of the station people. Mrs Stephen represented Mrs Bulmer as a defenceless ‘old lady’ who depended upon her daughter’s regular ‘help’, and who was ‘afraid for me to write to you, because she said Captain’s word would be taken first’:

I say again it is selfish & mean of him to want Blanche from Mrs Bulmer … very unkind of the Captain to wish to take Blanche from Mrs Bulmer as the lady is getting old & needs help.[17]

Howe was outraged, countering that Emily Stephen ‘defies me … she goes round to all the blacks and the Bulmers telling them that she has the “Board” on her side …’.[18] He was certainly not above exploiting existing tensions on the station (or ‘party feelings’) himself in his efforts to get Mrs Stephen driven off the station. Howe’s complaints against Mrs Stephen would be echoed in those he made against Mrs Bulmer a few years later, and suggest that Mrs Bulmer may have had good cause to fear him. Mrs Stephen, wrote Howe with open venom,

has told so many malicious lies about us that if she were a white woman instead of an evil minded black gin I should prosecute her communally … Emily keeps the whole station in a state of ferment & while she remains here there will be no peace.[19]

Mrs Stephen was indeed forced off the station in October of that year (1911),[20] so she was no longer there when Mrs Bulmer was facing eviction two years later. Her experience at the hands of Howe gives us an insight into the kind of ‘unpleasantness’ Howe felt obliged to ‘avoid’ when John Bulmer was alive. The conflict itself provides clear evidence of solidarity between Caroline Bulmer and the Lake Tyers people, alluded to by Howe in his 1913 complaints about the widow’s misplaced sympathies.

Of course, Howe’s personal hostility does not explain the Board’s determination to expel Mrs Bulmer (or indeed Mrs Stephen). The Board members had been impatient with Howe over the case of Mrs Stephen. ‘[A] little gentle advice may probably have the effect desired so that the intervention of the Board would not be necessary’, they admonished him in response to his first request to have her removed.[21] It was only his consummate failure to exert his authority effectively, the evidence of which he provided in such detail in his complaints, that compelled them to intervene in that instance. Now, in relation to Mrs Bulmer, the Board responded cautiously, and relatively slowly, to his reply of 22 September.

Although the exact order of events is unclear, the Board’s request to Howe for further information was dated 19 September, the day after the Member for Gippsland North, James McLachlan, forwarded the second petition from Lake Tyers Station to the representative for the Lake Tyers district, the Member for East Gippsland, James Cameron. This second petition, which had significantly revised the original and was open in its criticism of the Board, had been sent to McLachlan, who now advised Cameron that he had ‘informed the petitioners it is in your hands’.[22] Cameron himself had just received a letter concerning Mrs Bulmer from a Mr HS Dickson in Melbourne. Probably drawn in through a connection with the Bulmer family, whom he appeared to know personally, Dickson asked Cameron to rectify this ‘injustice’: ‘it seems a very hard and cruel thing, to treat his widow like this … Surely the old lady can be left in her house, and receive supplies for the year or two she might live’.[23] Cameron, it seems, then passed the assorted correspondence to the Chief Secretary, who was also the Board’s chairman. It was then referred directly to the Board for consideration on 20 September – two days before the date of Howe’s reply. Meanwhile, the Board’s secretary had also received a second letter from Mrs Bulmer (dated 19 September, the same day that they had first asked Howe for more details), asserting the validity of her claim to the house her husband had built.

The extension of the matter into the wider public domain and especially the interest of two parliamentarians may well explain the Board’s hesitancy at this point. Mrs Bulmer and Howe were directed on 2 October that ‘existing arrangements will not be disturbed for the present’.

A month later the Board had arrived at a considered opinion on the matter. In a letter to the Chief Secretary (who, as already noted, was chairman of the Board), dated 24 November, the secretary recorded the bland explanation that the Board felt ‘that in the best interests of the station it is advisable that she [Mrs Bulmer] is not permitted to remain’. The point was clarified in the minutes of their discussion on the question in the New Year, 1914:

The Board thinks that a continuation of residence is not desirable, as discipline is interfered with, since from long association, the Bulmer family necessarily retains a strong influence over the aborigines.[24]

Whether beyond their understanding, or simply their capacity to express it, the fact that Aboriginal people had taken the initiative was not allowed for in this record of the Board members’ view. Nevertheless, the intervention of the Aboriginal people at Lake Tyers to help Mrs Bulmer, in the face of the manager’s overt hostility, was the foremost reason the Board decided to support the latter’s position. It is therefore worth returning to a closer consideration of this second petition.

Faced with no response to their original petition (other than the peremptory letter sent to Mrs Bulmer), in early September 1913 the Lake Tyers residents had approached Percy Pepper, a man living off the reserve, for help. Pepper re-wrote the petition for them and included a statement describing his role at the bottom: ‘I, P. Pepper Half Cast Cunninghame who has Relations on Lake Tye[r]s Knowing what the People want and Acting as Leader of this Petation my Siginiture Percy Pepper’. By now the list of signatories had grown from 42 to 53 (including Pepper and his two witnesses). The first petition had been headed by John McDougall and his wife Bella (in what seems to be the tradition of Lake Tyers petitions, men’s names were generally listed in a column on the left, and women’s on the right) and while the order of the names had changed somewhat, the name of John McDougall still headed the list. As van Toorn points out, the order of names listed on Aboriginal petitions signified the ongoing recognition of authority within Aboriginal communities that was being subtly asserted in formal correspondence with the white administration. Pepper, originally from Ramahyuck Mission and forced away by the Aborigines Act 1886, was married to a woman from an original Lake Tyers family, and, as John McDougall’s wife was the aunt of Pepper’s wife, it may have been through this connection that Pepper was approached.[25]

Van Toorn has written more extensively on the BPA archives in her recent book, Writing never arrives naked, in which she makes the point that the Victorian authorities used writing as a self-protective distancing device – that is, orders to be carried out on the stations were sent by the authorities comfortably ensconced in their Melbourne office, while the Aboriginal writers used the same tool to bridge the social and spatial divide between themselves and those who could help them, evading the ‘proper’ channels of communication to write directly to those in positions of higher authority. Furthermore, van Toorn speculates, for Aboriginal people ‘the written petition had to be delivered as though it were an oral message‘ in order to be considered effective, both in terms of the white man’s criteria for authenticity, and to satisfy their own cultural precepts: ‘Power and meaning did not reside inherently in the alphabetically written document itself, but were activated through the ceremonial process of its face-to-face delivery and re-voicing’.[26] In fact, when Pepper forwarded this second petition to McLachlan, he explained in a cover note his intention to come to Melbourne in the company of ‘The oldest Aboriginal’ on Lake Tyers and one of that man’s sons. They would present the petition ‘our Selves’ to the Governor, wrote Pepper, as the Board ‘have not given us Satisfaction to the last Petation we sent in’:

… we think it is better to carry the Petation and any question we will answer or rather the 2 men I take down will as one of them was in his wild State when he first knew Mr and Mrs Bulmer ….

They wanted to call upon McLachlan as well, to ‘let you know every thing also show to you some of the Aboriginals Complaint how things are carried on’. Face-to-face contact could serve pragmatic reasons as well as ceremonial, of course, allowing opportunities to elaborate and argue that were not necessarily available or possible in the written text.

While respectful, the tone of Pepper’s letter was not that of a supplicant. Pointing out that he realised that McLachlan was not the member for their electoral district, he explained that he had taken the parliamentarian ‘into Confidence’ on behalf of ‘our People’ who were ‘unsettled about what is to become of Mrs Bulmer and also the daughter …’:

[A]though they [the Lake Tyers people] have no Say in putting men in Parlement the Same as I do as I am a half cast they look to me to help them the Same way as I look to you for help … I hope and trust you will help us with the Pass [to come to Melbourne by rail] as it is no good to write to the Board of Protection as they would not give us one …

Pepper concluded his letter, having emphasised that the petition was ‘for Miss Bulmer and Mrs Bulmer to remain … we intend to get it through’, by making one final appeal for clemency that sits somewhat incongruously, if not impossibly, with the assertive tenor of the rest: ‘it is for the sake of a Race that will soon die out trusting you will help’.

The petition itself had been substantially reworked from the original, particularly in the vigorous exposition of the petitioners’ reasons for caring about Mrs Bulmer’s fate (the original, as we have seen, expressing only their loyalties to her late husband). Opening with the heartfelt plea that the Governor ‘give to us the People we would Love to be amongst us’, the statement emphasised the close and filial affection the petitioners felt for Mrs Bulmer. She had ‘been like a mother to us … we all want her to Live the Rest of her Life with us’. Those of ‘our Parents’ who had known Mrs Bulmer when they ‘were young and in their Wild state’ did not want Mrs Bulmer to ‘go away from them’, while those of the younger generations who had been ‘braught up with the Bulmer Family’ considered that ‘it will be very hard for them to Part from us’.

At the same time, concerns about the future of the station under government administration, discernible in the first petition, emerged more strongly. This was framed through the device of Mrs Bulmer’s continuing motherly care, despite her removal from any position of responsibility with the new management:

… we know the help Mrs Bulmer and Miss Ethel Bulmer has given in the time of Sickness not only when they had the Station but after Mr Bulmer had handed it to the Present Manager and his wife although Mrs Bulmer has nothing to do with the Mission She still Looks after us in the time of trouble in the way of a Mother she Loves the Blacks and we love her we do beg to have her and her daughter with us not only for the our Selves but for the sake of our Children …

They had ‘heard no more about’ the petition they had sent to the Board, and so they had ‘made up our minds’ to see the Governor himself, believing he would see they were ‘treated in the Proper way’, again implying that the Board itself would not. Indeed the petitioners concluded that Mrs Bulmer’s eviction represented a state of affairs at Lake Tyers that demanded investigation into the Board’s administration: ‘the Station is a place that want to be seen into by some one who will look into things and they will know’. In this way, Mrs Bulmer’s plight became a symbol of Aboriginal grievances against the new government regime, and a cause that might motivate other white authorities to take their grievances seriously. Her treatment was, perhaps, an ‘injustice’ that would outrage all.

At the point at which this petition arrived at the Board’s office, as we have seen, the Board put the decision on Mrs Bulmer’s eviction in abeyance while they assessed the situation. However, the hostility to the Board revealed in the second petition, and the Aboriginal effort to wield resistance it represented, could only have hardened the Board’s resolve. In many ways the two petitions reflected a general air of unrest amongst Victorian Aboriginal people that had been evident for some years. John Bulmer himself had written sourly of the young ‘half educated fellows’ who used their ‘powers of writing’ to ‘air their supposed grievances’ by writing to the Governor, or interviewing a member of parliament.[27] One can only wonder what he would have made of the Lake Tyers campaign on behalf of his widow. But in the eyes of the Board it could only be a demonstration of Aboriginal subversion at a crucial time of regime change, organised around the figure of one who stood for the missionary control of the past. In 1915 legislation would be passed extending the government’s powers over all Aboriginal and mixed-descent people in the state. The intent had long been to make Lake Tyers the centre for a Board policy of forcibly ‘concentrating’ all remaining Victorian Aborigines onto this one reserve. This was finally formally fixed upon by the Board at a meeting in 1917, by which time James Cameron, along with other parliamentarians ‘in whose districts aboriginal stations or depôts existed’, had been appointed to the Board.[28] Mrs Bulmer had to be expelled. Not because her presence in itself threatened the government (for, indeed, she may well have been allowed to live out her days in peace, had there been no petition), but to demonstrate to the Aboriginal residents the resolution of the state authorities and the futility of any attempts to resist. Had Pepper been able to deliver the second petition in person we can assume the outcome would have been no different. In hindsight, the campaign looks remarkably naïve. It not only backfired for Mrs Bulmer – remembering that the Lake Tyers residents and not she had apparently taken the initiative – but in the end was quite clearly unsuccessful in terms of changing the power relations both on the reserve and between Aboriginal people and the Board.

But to interpret this episode, this small lost cause, purely in terms of its outcomes is in a real sense to miss the point. In acting to support and endorse Mrs Bulmer’s claim to stay at Lake Tyers, the Aboriginal petitioners seized upon an opportunity to make known their wider concerns about their collective futures at a key moment in their history, intervening at a vulnerable point of rupture between the old (missionary) and the new (secular state) forms of management and indeed colonisation. Regardless of both the motivation and the outcomes, this was at once an assertion of the central and ongoing importance of land and community connections to the residents of Lake Tyers, and an assertion of the rights of the people of the land and community to manage their own affairs – at root, to decide and announce who was to live among them. Revealing a humanity and generosity of spirit that resided at the heart of the Aboriginal community of Lake Tyers, the petitions showed the resilience, also, of a deep sense of Aboriginal authority that had abided through generations of violence, dislocation and missionary control, and that stood in open challenge to the growing power of the state in the opening years of the twentieth century.

Endnotes

[1] Caroline Bulmer to the Secretary, Board for the Protection of Aborigines (hereafter BPA), PROV, VA 515 Board for the Protection of Aborigines, VPRS 1694/P0 Correspondence Files, Unit 6, Bundle 2, 8 September 1913. Unless otherwise indicated, correspondence files referred to in this article are found here.

[2] Petition to BPA, PROV, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 6, Bundle 2, undated but received 18 August [1913]; ‘Petition From Lake Tyers Mission to the Governor of Victoria’, ibid., Unit 12, Bundle 4, 9 September 1913. This second petition includes a covering letter by Percy Pepper, who assisted the residents with its preparation and delivery (discussed below).

[3] Secretary, BPA to Caroline Bulmer, 3 September 1913 (copy).

[4] See, for example, the collection of letters in E Nelson, S Smith & P Grimshaw (eds), Letters from Aboriginal women of Victoria 1867-1926, History Department, The University of Melbourne, 2002.

[5] P van Toorn, ‘Hegemony or hidden transcripts?: Aboriginal writings from Lake Condah 1876-907’, in L Dale & M Henderson (eds), Terra incognita: new essays in Australian studies, API Network, Perth, 2006, pp. 15-27.

[6] ‘Introduction’, John Bulmer’s recollections of Victorian Aboriginal life, 1855-1908, compiled by Alistair Campbell and edited by Ron Vanderwal, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, [1999?], p. xvii.

[7] P Pepper with T De Araugo, What did happen to the Aborigines of Victoria, vol. 1, The Kurnai of Gippsland, Hyland House, Melbourne, 1985, pp. 222-7.

[8] ibid., p. 229.

[9] H Carey, ‘Companions in the wilderness? Missionary wives in colonial Australia, 1788-1900’, Journal of religious history, vol. 19, no. 2, Dec. 1995, p. 240.

[10] John Bulmer’s recollections, pp. 35-6.

[11] Pepper & De Araugo, op. cit., p. 227.

[12] ibid., p. 230; Caroline Bulmer to Secretary, BPA, 8 September 1913.

[13] There is correspondence between a Robert Bulmer and the Secretary, BPA, in January and February 1918. Robert Bulmer’s letterhead reveals that he was a timber merchant. See also P Pepper, You are what you make yourself to be: the story of a Victorian Aboriginal family 1842-1980, Hyland, House, Melbourne, 1980, p. 83.

[14] Howe to Secretary, BPA, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 12, Bundle 4, 31 August 1914.

[15] Minute dated 22 September 1913.

[16] Pepper, You are what you make yourself to be, p. 83.

[17] Emily Stephen to WA Callaway, Vice-Chairman, BPA, PROV, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 7, Bundle 3, 28 February 1911, 30 March 1911, undated but registered 27 June [1911]. See also Nelson, Smith and Grimshaw, Letters from Aboriginal women of Victoria, pp. 165-6, 169-72.

[18] Howe to Secretary, BPA, PROV, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 7, Bundle 3, 3 April 1911.

[19] Howe to Callaway, ibid., 9 August 1911.

[20] See Nelson, Smith & Grimshaw, Letters from Aboriginal women of Victoria, pp. 172-5; and Pepper & De Araugo, pp. 236-8.

[21] [Callaway] to the Manager, Lake Tyers, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 7, Bundle 3, 10 April 1911 (copy).

[22] James McLachlan to James Cameron, PROV, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 12, Bundle 4, 18 September 1913.

[23] HS Dickson to James Cameron, ibid., 15 September 1913.

[24] Minute, BPA, PROV, VPRS 1694/P0, Unit 6, Bundle 2, 2 January 1914. Notes and minutes regarding Mrs Bulmer continued in the following months.

[25] For the Pepper family connections see Pepper, You are what you make yourself to be, especially pp. 11, 30-3, 43-5, 51, 52; also Pepper & De Araugo, op. cit., p. 240.

[26] P van Toorn, Writing never arrives naked: early Aboriginal cultures of writing in Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2006, pp. 195-6, 143-4 (original emphasis). In Chapter 6 of this book, van Toorn writes extensively on the petitions from another Aboriginal Station, Coranderrk (pp. 123-51).

[27] John Bulmer’s recollections, p. 88.

[28] 49th Report of the Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1922. This report for 1921 was the first report presented by the Board since its last in 1912. For the Aborigines Act of 1915 and the introduction of the concentration policy, see Pepper & De Araugo, pp. 241-8.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples