Last updated:

‘Colac 1857: Snapshot of a Colonial Settlement’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 7, 2008. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Dawn Peel.

It began as a challenge: the extent to which I could identify the people living in my home district of Colac in 1856-57, the first year for which there was any sort of list with which to begin. Using this list, the electoral roll current for twelve months, I found it led to many other records. The assumption that, to be on the roll with its property qualification, most of the men would have been established in the district and probably married, led to indexes of marriages and births. The birth certificates subsequently purchased revealed many more names – wives, other children, midwives, informants. Family histories identified some deaths, leading to certificates which gave more names than that of the subject, which were then added to the list. Accidental deaths were investigated by an inquest jury – more men. Did any of them have wives? To the immigration indexes to see what could be found! Although there was no local government in my area there were court and school records to follow up. Living in the district also gave me easy access to local historical groups with family files and useful indexes to investigate as well as names to check in formal records.

It became clear that it was indeed possible to find a range of people who roughly corresponded to those found by the census when it was taken in March 1857. By then the database being built up was also beginning to reveal more than had been anticipated. The length of time people had been in the colony was one feature which showed clearly the impact of the gold rushes on what had been previously a little pastoral settlement. Areas of origin and methods of arrival suggested other social divisions in the community.

The people in my database began to acquire individuality and their interactions could be seen in this light. In many of the records of local institutions which then came to life, the forging of community spirit could be seen. The relevance of local events in the context of the wider theatre of Victorian colonial life also became clear. While this proved to be a successful endeavour, one which unexpectedly led to the publication of a book, Year of hope: Colac in 1857, it could, for that year, be more difficult for larger areas (Colac in 1856-57 was the smallest electorate in the colony). However, the study of a slice of the population at a chosen time could clearly reap unexpected rewards.

What was life like in a settlement in rural Victoria immediately following the gold rushes?

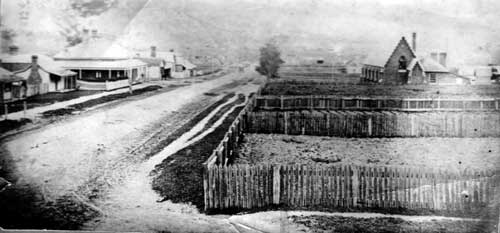

The history of white occupation of the Colac district dates back to 1837, making it one of the oldest inland settlements in the colony, and thus one which experienced all the major waves of immigration. A census conducted in March 1857 collected vital statistics about many aspects of Victoria’s population, analysed by counties, electoral provinces and electoral districts. Colac was the smallest electoral district in the colony, and the list of its voters was correspondingly small. This district therefore presented both a varied population and an area of manageable size to study.

It was a settlement isolated in many ways by its geographical position. Situated on the southern banks of a large body of freshwater that white settlers named Lake Colac, the small township was on the edge of extensive plains – occupied as grazing land mostly under Crown tenancy by eight squatters. The settlement was 40 miles (64 km) west of the port of Geelong and there was no public coach service from the coast for the last half of the journey. Travellers sometimes took up to three days to complete the trip, so bad was the route at times of the year. Travel further west from Colac was blocked by a stretch of volcanic stony rises, an area of dense scrub and undergrowth, weird geological formations, and also a feared reputation resulting from stories of robberies and attacks that had occurred in its strange environment. As a result, most traffic from the next small settlement, Camperdown, by-passed Colac by travelling north of Lake Corangamite, a large area of shallow saline water, which effectively hemmed in the Colac district from the north-west. The route to Ballarat, 60 miles (97 km) north was a rough unformed track winding over the plains. To the south the Otway Ranges created another barrier. There was therefore a largely enclosed area from Winchelsea to the stony rises, sparsely populated, with the small settlement as its node. This was chosen as the study area.

The 1857 census revealed that while there were 792 people in the small electoral district incorporating the Colac township, 41 per cent of them were under 21 years of age. These included 208 children under seven and another 129 between seven and fourteen. In the surrounding pastoral land there were small clusters of settlement at the station homesteads, scattered shepherds’ huts, and a limited area of agricultural land at Larpent seven miles (11 km) west of the town. There were 207 males and 149 females of all ages, ‘exclusive of unemployed Aborigines’ as the census return stated, in these rural districts.[1]

How to find these people was the first problem. The only official sources of names initially appeared to be the electoral rolls for Colac and the surrounding countryside, and these became the starting points.[2] They yielded the names of 166 men, 127 of whom lived in the immediate Colac area. The franchise included a property qualification and so it was reasonable to suppose that many of these men had been in the district long enough to establish a stake there, and that they had also established families. This led to the index to births being the next resource to be consulted, and by entering the name of the voter it was established that indeed many of the voters were married men whose wives had given birth in the district. The first women were added to the list. As the index could also be searched by location and date, other married women who had given birth in the area during 1857 were identified. When sibling births were found spanning 1857 it seemed reasonable to presume that these were in families who were there in that year. All the birth certificates for Colac in 1857 were subsequently read and these proved invaluable, containing not only the names of the parents and siblings, but also those of witnesses, midwives, accoucheurs and the registrar. More people and their families to pursue! Indexes could not be searched by district for deaths but when these were identified from family histories they led to certificates rich in names – informants, doctors, undertakers, witnesses to the burial and sometimes an officiating minister. Marriages were fewer, but some certificates were sighted, with similar rewards.[3]

Colac and District Historical Society.

A laborious task was finding single men and women who had arrived during the target year. Here the online index to Assisted British Immigration 1839-1871 proved invaluable. It was possible to isolate the ships that had arrived in Victoria that year and in the preceding months, and by scanning the microfiche disposal lists it was possible to find local men who had employed the new settlers and so identify the young men and women who came to the district as their employees. Most new arrivals came on at least three-month contracts, so were in the Colac district for some part of 1857, and very often for longer.[4]

Unassisted immigrants who came to the district were harder to find, there being no convenient disposal lists to suggest where they went after their arrival. Early in the project there was only a card index, in which the arrival date of settlers said to have been in the district in 1857 could be confirmed. The subsequent publication of an online index meant that, if the name of a ship were known, this resource could be used to pinpoint arrival date in the colony.[5] For many migrants the ship on which they had made the momentous voyage across the world remained part of their identity, and was mentioned in obituaries and family histories. People admitted to the Colac hospital had the ship of arrival entered as part of their admission details and searching indexes by ship and date led to names of extended families whose presence in Colac could be further investigated.

Sometimes, when a man had obtained respectability before his death, it appeared that an obituary almost carefully avoided naming a ship or date of arrival. This would indicate that a possible convict past warranted investigation. Tasmanian births and marriages often confirmed that the person had lived in Van Diemen’s Land, leading to further searches in the many convict records available that could occasionally reveal more. For some people thus identified it was possible to ascertain when they had crossed the straits to Victoria.[6]

The local court records before 1858 could not be found, but the records of inquests were rich in names. Inquests were conducted in front of a jury, and not only were jurors’ names, occupations and degrees of literacy revealed in these documents, but sometimes vivid accounts were given of the circumstances surrounding the death.[7]

A search of the local cemetery records led to the identities of many older people who died later in the century. Their obituaries in the local papers sometimes told how long they were said to have been in the district and, when relevant, this could often be confirmed by the immigrant indexes and disposal lists. Their wills provided leads to family members who could be further checked for their presence in the area. Family histories and pioneer registers provided many useful leads, as did an antiquarian history of the town written in 1888,[8] but no one was included on the list unless contemporary documentation confirmed their presence.

Slowly the list grew and finally contained over 1300 names, including children. This was more than the census-taker had found in the area in March 1857, but included people who had been there before the census and subsequently moved on, and those who had arrived later in the year.

When the list of names was analysed it became clear that over half the adult population was post-gold-rush, having arrived in the colony after the end of 1852. The occupations of the men, as revealed in the census, demonstrated the effect of the demand for housing. While general labourers and those engaged in agriculture and pastoralism were the largest group in the population, the next major male employment category was related to construction. The twenty-eight builders, carpenters and timber merchants were supported by wood-splitters, quarrymen and brickmakers, masons and bricklayers. The skills which the more recent migrants brought with them were also clear. The clergyman, surveyor, coachbuilder, clerk of courts, and teachers were all post-gold-rush settlers.

Amongst the women, ‘wives and widows of no specific occupation’ were by far the largest group. Domestic servants followed, then needlewomen and a few farm workers, inn servants and shop assistants.

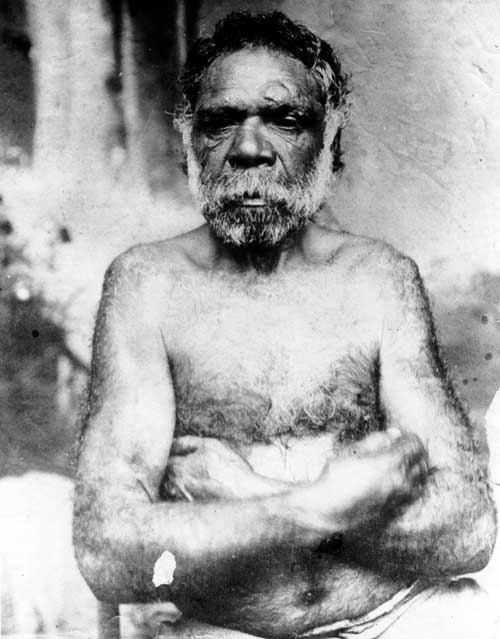

There was one group of local residents not recognised by the census – the members of the local Aboriginal tribe, the Coladjins. However, a questionnaire returned to the government early in 1858 revealed that the group consisted of twelve men, six women and one boy of six years. The report estimated that when white graziers first arrived, twenty years before, the Colac tribe had numbered about thirty.[9] Most of the Aboriginal men were intermittently employed by the settlers and farmers at a rate of wages about half the current wages of Englishmen. The nucleus of the group camped on a volcanic hillside north of the town.

Colac and District Historical Society.

While most official documents ignored this group in the target year there was a good deal of information in the official records on interactions amongst the white settlers. It was clear that some events crossed the bounds of origin and class and brought people together, whilst others demonstrated schisms in the evolving community. Inquest juries, where ‘respectable householders’ sat ‘in sight of the body’, were amongst the former.

Despite the property requirement, the jurors had diverse backgrounds, and jury service added to the multiple social relationships developing in the small settlement. The inquest for James Long, a tutor who struck his head after falling from a horse, brought together a carpenter and a builder, both from England; two storekeepers and the poundkeeper, all from Scotland; and an agriculturalist and a storeman from the north of Ireland.[10]

When George Keppell was found dead near Lake Colac in November 1857 the cause of his death was determined by a more varied group of men.[11] John Rea and his brother Adam Rea were literate Scotsmen and Rea’s general store was an important landmark on the edge of the town. Another Scotsman was Thomas Hill, educated, combative and outspoken. He had opened the first rough hotel in Colac in 1848. When the first blocks of suburban land were sold it was said that the only buyers were squatters and publicans, and Hill obtained a number of pieces of land. He had at times held a mail contract, and set up a sawmill, and on the 1856 electoral roll was listed as ‘miller’ as he then had a flour mill. He and his wife had a growing family and he was passionate about the development of the town, going out of his way to attract migrants with skills to Colac, and sometimes renting them their first accommodation.

Also on the jury for Keppel was one of the men Thomas Hill had attracted to the district, Simon Campbell, a skilled blacksmith from County Clare. He had a thriving business in the town, and links by marriage to other families of similar origins. Another Irishman and also well-established in the town and a member of an extended family there was John McGonigal.

William Martin, an orchardist from Yorkshire, John Gibson, a shoemaker from Ayreshire, and another shoemaker, John Black, from County Tyrone in the north of Ireland, were also members of this jury. Other juries were similarly mixed. It is difficult to imagine circumstances which could have brought together such disparate men before their migration, and in the isolated settlement they were jointly brought face to face with raw death.

Less exceptional deaths also forced a deal of interaction between various local people. Legal requirements surrounding a death involved the deputy-registrar, a doctor or coroner, an informant, an undertaker, a minister or witnesses – usually a minimum of five people. During most of 1857 the local deputy-registrar was Cornishman Henry Nankivell, who usually also certified the death in his role as doctor. The Reverend Hugh Blair from the north of Ireland was the only resident minister of religion and frequently signed the death certificate as one of the witnesses of the burial. Robert Shields, a carpenter from Ireland, co-signed with Blair as a witness to the burial of Donald McDonald, a general servant of Scottish birth, whose father was the informant of the death. There was no official undertaker in the town and Shields provided this service for McDonald. However, in other cases the provision of a coffin and associated duties led to a number of different men, sometimes carpenters, sometimes family members and sometimes friends, acting in this capacity. During four weeks in April 1857 sixteen different people were involved in the legal and physical requirements surrounding local deaths.[12]

Common emotions that might have been part of a shared involvement in local deaths were never enough, of course, to ensure a homogeneous community. Divisions were created by the origins of the settlers, class, religion, and, above all during 1857, by the burning question of access to the Crown land which surrounded the township – land leased to the squatters who were hoping to be able to obtain freehold to it. Many of these divisions reinforced each other, and the birth certificates reveal one of the ways in which people were separated by class and origin.

Mary Anne Johnson was an experienced midwife, in demand among the Colac settlers with links to the convict population of Van Diemen’s Land. Poor economic conditions in the island colony had led to numbers of ex-convicts, many with families, making the often difficult voyage across Bass Strait to seek new opportunities on the mainland. Amongst them was a family linked by their connections to a former convict, William Massey. Massey, in 1830, at the age of 33 years, was convicted of theft in the County of Buckinghamshire and sentenced to fourteen years transportation. His wife Susannah and their five children were later permitted to join him in Van Diemen’s Land, and by the time of his death in 1841 their family had increased by a further three children. Susannah subsequently married another ex-convict, Thomas East, and by 1857 their large inter-connected family group of seventeen formed a significant part of the population in Colac. They included Susannah’s daughter Mary Anne and her husband Edward Johnson, with their three daughters and four sons. One of the daughters, Louisa, was married to a former convict exile, Charles Merrin, and had by 1857 borne three children. Mary Anne’s husband, Edward Johnson, was one of at least seven men on the electoral roll who had been convicted in England, but who, as early settlers in the district, had been able to acquire enough land to entitle them to a vote in 1856-57. Mary Anne Johnson had midwifery skills learnt from her mother Susannah Massey/East. Birth certificates show the extent of her contacts in Colac amongst the former Van Diemen’s Land residents, suggesting that people with this background formed a distinct group in the settlement.[13]

Birth certificates also show the other side of the coin. Jane Hebb and her husband, Charles, a well-educated man who had been a bookseller in Leicester, together with their six children, migrated unassisted during 1852. Jane, who was forty-six years of age, was regarded as a skilled midwife, noted for her gentle ways, her healing hands and her knowledge of herbs.[14] The women she helped were all free settlers, and all people who could afford the services of the only practising doctor, Henry Nankivell.

However births, like deaths, called on the settlers’ common humanity, so there were also patterns which, while they might indicate distinct groupings in the community, perhaps did so less than it initially appears. The slight tendencies for a birth attendant to have been from the same part of the British Isles, from the same class in society, or of the same religion, could also be accounted for by the fact that many of the helpers were either family members or neighbours.

There was evidence of some co-operation amongst the different religious groups. The subscription list for a new Catholic schoolhouse carried the names of prominent Protestant squatters. Hugh Murray was a staunch Presbyterian. In 1837 he had driven his sheep into the unoccupied land around Lake Colac and established his Borongarook run. Over time he had become the leading citizen of the district, a magistrate, a patron of the school, and the local contact for any government business. He and his brother-in-law, John Calvert of the Irrewarra run adjacent to the town, had worked together to make land available for a new Presbyterian Church and to obtain subscriptions from its supporters. Both these men were subscribers to the fund for the Catholic schoolhouse, as was Murray’s brother Andrew of Wool Wool run and his brother-in-law, the squatter Dr David Stodart, of Corunnun. The fiercely independent Thomas Hill was another Presbyterian whose name was amongst the sixty-seven subscribers.[15]

Colac and District Historical Society.

There was no Church of England and the newly-opened Presbyterian Church was the main centre of Protestant worship. Many people who later became part of a Church of England congregation were amongst those who met there on a Sunday. There had earlier been co-operation between the Presbyterians and Methodists, who held services in Hugh Murray’s barn, and they later shared a simple building known as Gow’s Chapel. When the new Presbyterian Church was built the Methodists were also able to use it. During 1857 they also held prayer meetings in a converted barn. A non-ordained Baptist preacher travelling in the district was asked to dine with Hugh Murray, given hospitality at the manse, asked to preach from the pulpit for the Presbyterians and invited to take a Sunday School class for the Methodists.

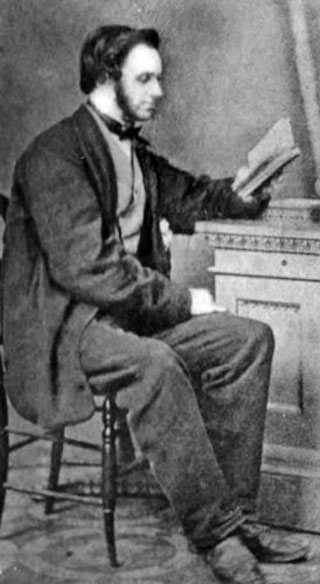

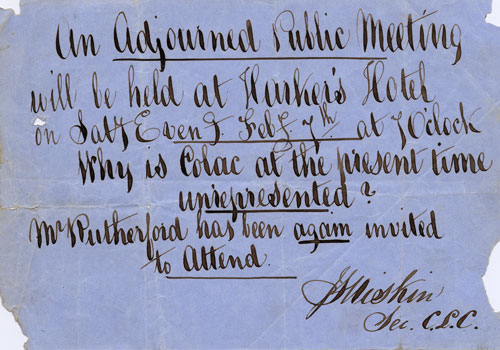

Great tensions were apparent in the community, however, over the question of ownership of Crown land, and, surprisingly, this was revealed in the records of the National School. The teacher, Joseph Miskin, had taken on the additional role of secretary of a local branch of a co-operative land society. Such societies enabled men with limited access to capital to pool their resources to obtain credit for the purchase of land. Even though most settlers aspired to own only enough land for agriculture, the very notion threatened pastoralists whose income depended on access to the extensive plains. Already at earlier district land sales squatters had seen small blocks carved from their runs, or been forced to pay well above the expected price for others in the face of the increasingly competitive bidding. Miskin’s activities in this sphere angered the local graziers, and, as they were amongst the patrons who supervised the school, they brought pressure on the Board of National Education to have the master dismissed. Joseph Scammel Miskin had been a teacher for fourteen years in England and, with his wife and family, had arrived in Victoria as schoolmaster on the Harpley in 1853. He was appointed to Colac in 1854, where previous teachers had either been unsatisfactory or had found the supervision of the school patrons, led by Hugh Murray, to be too demanding. Miskin was not going to be cowered by a colonial grazier, and his wider involvement in local life led to him becoming a spokesperson voicing much discontent.

Colac and District Historical Society.

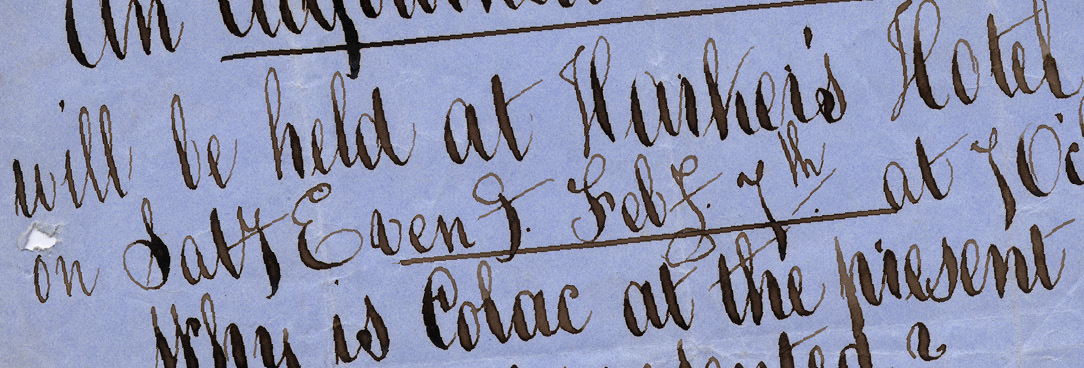

When the National School Board did not respond immediately to requests to remove the master, most of the school patrons, including the grazier members and others clearly influenced by them, resigned and a new school committee was appointed early in 1857. In February, Miskin further angered the squatter element in the community by acting as secretary of a local committee pressing for the resignation of Andrew Rutherford as the local Member of Parliament in the newly constituted Legislative Assembly. There was a widely held belief that Rutherford, in parliamentary debates on the land question, had acted in the interests of the graziers.

The views of the former patrons reached the ears of School Inspector Glen, who had often met with them when visiting the school. He reported to Melbourne that the newly appointed group of patrons had too many of its members, ‘mere creatures of Mr J. S. Miskin, the Master, ready to support him on all occasions in consequence of certain business relations in which he stands to them out of doors’.[16] The National Board then sent Inspector Bonwick of the Denominational School Board to obtain an objective view of the troubles. After dining with Hugh Murray, Bonwick was able to elucidate further. He explained that Miskin was said to ‘have neglected his pupils, going away on land jobbing tours for a week at a time’.[17]

PROV, VPRS 880/P Inwards Registered Correspondence, Unit 11, Colac.

The National School Board acted and Miskin was dismissed.

There was a public uproar. Meetings were held and letters flowed to Melbourne. One was quite explicit. After stating that the people were perfectly satisfied with Miskin they claimed that his enemy was a squatter who was trying to remove him because, as the agent of the Colonial Freehold Land Society, Miskin had been the means of procuring some of the squatters’ runs for the Colac people.

The issue was finally resolved. Miskin’s dismissal remained, but a new set of school patrons, acceptable to both the Board in Melbourne and the Colac people, was negotiated.

The people publicly involved in this issue were men, and mainly men whose presence in the settlement had pre-dated the gold rushes. Not all of them had children and others had children whose education would not have been at the National School. Henry Nankivell, for example, was single and someone who in his role as doctor mixed more widely in the community than the Murray family, with whom he was connected by marriage. Alexander Dennis held an extensive squatting run east of the town, and unlike the other district squatters had not lived in class-conscious Van Diemen’s Land. He came to the area with his family directly from Cornwall in 1841 and was a staunch Methodist. The dissident group had suggested him as a new patron. Irish Catholic Patrick Danaher’s colonial life dated from his arrival on the Lady Peel in 1850 as one of several immigrants sponsored by Lord Monteagle. There had always been a Catholic patron on the board of the local school, and Patrick, although now engaged in the profitable business of carrying to the goldfields, had a family in Colac and was a literate and respected citizen, and was seen as an appropriate person to be nominated. Thomas Hill, always ready to face up to the squatter class, was also outspoken at meetings of this group. The interconnected issues of land, school, and politics thus revealed both increasing fractures in the local society and disinterested people prepared to act together for the perceived common good.

Presumably there were women of the community vitally interested in the welfare and education of their children, but public records do not reveal this. Apart from the bald numbers on the census returns, and civil registrations, very few official records were found which shed any light on the activities of the women. While there are no extant court records for Colac during 1857, one Colac case did reach the Geelong court. A young girl of eight-and-a-half years had been sexually assaulted after being enticed with sweets into a hayfield on the outskirts of the town. Jane Gears appeared as a witness at the trial, giving an identity to one of the three women storekeepers identified by the census. She told of the child coming into her store with money for a shilling’s worth of biscuits. The accused man had been in the store at the same time and the two left together. Gears, a childless, married Irishwoman, signed her deposition in a firm and practised hand. Maria Troy’s signature was also firm but perhaps not as confident. She had seen the two in the field and when she came out her door the accused man went the other way. Brigid Anthony, working in her family’s hotel, saw the two leave the field separately and recalled the prisoner coming in for a nobbler after being seen with the child. Brigid, too, was literate. Sarah, the child, was taken by her mother, a 46- year-old, well-educated settler of several years’ standing, to the doctor for examination on the evening of the assault.

A glimpse into another woman’s possible hard lot came in the files of the Geelong Police District. Amelia Pearce had given birth to a son, Robert, in Melbourne, shortly before her husband, Constable Robert Henry Pearce, was transferred with little notice to Colac. Sergeant Cahir in Colac was instructed to advise Pearce about finding a hut as lodging for his family, and permitted him to take the Colac police horse and cart to Winchelsea to collect his wife and child, who would have had to travel there by ship from Melbourne to Geelong and thence by coach to Winchelsea.[18]

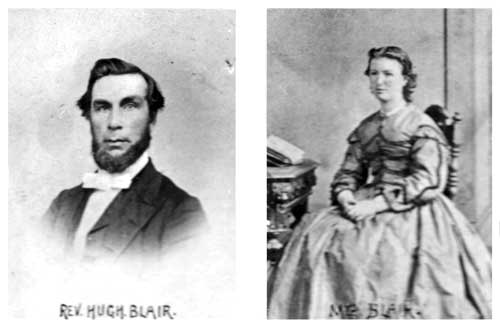

Another young wife had a very different life. In 1854, at the age of seventeen, Annie Blair and her husband Reverend Hugh Blair, who was sixteen years her senior, arrived in Melbourne aboard the SS Great Britain. Blair’s appointment to Colac followed and in 1857 the couple moved to the newly completed manse. Here the young woman, now with a one-year-old son, Hugh Murray Blair, was frequently required to entertain official visitors to the town, often accommodating groups of six or seven people. There are occasional glimpses of her witnessing a marriage when a wedding took place at the manse.

Colac and District Historical Society.

Some women appeared as inquest witnesses. We learn that Isabella Pink was married to a timber worker who was away in the forest for up to two weeks at a time, leaving her with two children under three years of age. Mary Doyle was seen staying for a week in the home of a settler outside the town, being prepared to help with an imminent confinement. Another woman was married to a man who had drinking bouts of two to six weeks. Maria James, the wife of a herbalist, had been consulted about the death of a man who suffered ‘stoppage of the bowells’.[19]

Three women, each the mother of a large family, were widowed during 1857. Seven experienced the death of an infant. Over half the women of child-bearing age had a child during the year, many of these infants, particularly those of the pre-1853 settlers, joining families where there were already five or six other children. Perhaps women were elusive when it came to creating a snapshot of the district in 1857 but their presence influenced so much else of what went on. The housing, the standard of the school, the employment of the men, and even the quest for land at every level of society, was of increased importance because of the substantial number of families making their home in the colonial outpost.

In compiling this snapshot, accounts of co-operation and of conflict in the little settlement were enriched as knowledge of the protagonists’ backgrounds, and perceived personalities became part of the story. Family histories and other contemporary sources added depth to the information that emerged from the official records. The particular nature of the Colac area – its discrete geographical boundaries and relatively small population with a stable element stretching back almost twenty years – was a key factor which made such a study possible.

Endnotes

[1] Census of Victoria, 1857: population tables, Registrar-General’s Office, Melbourne, 1857.

[2] Rolls for the electoral districts of Colac and of Polworth [sic] and South Grenville, and for the divisions of Colac and of Polworth and South Grenville in the South-Western Province, all current from 21 July 1856 to 30 June 1857, both days inclusive.

[3] Pioneer Index, Victoria 1836-1888.

[4] Assisted passenger lists, 1839-1871 (online searchable index to VPRS 14 Register of Assisted Immigrants from the United Kingdom, 1839-1871).

[5] Unassisted passenger lists, 1852-1923 (online searchable index to VPRS 947 Inward Overseas Passenger Lists, 1852-1923). This was accessed online as it progressively became available as a searchable index.

[6] PROV, VPRS 944/P0 Inward Passenger Lists (Australian Ports), Units 10, 11 and 12; Papers of the Geelong and Portland Bay Immigration Society, held at State Library of Victoria, MS 12232.

[7] PROV, VA 2889 Registrar-General’s Department, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files.

[8] I Hebb, The history of Colac and district, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1970, reprinted from serial publication in the Colac Herald, 1888.

[9] Returns on a Circular on Aborigines, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, (Legislative Council) 1858-59, p. 634 and following.

[10] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 47, Item 1857/1020, James Long.

[11] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 47, Item 1857/991, George Keppell.

[12] Deaths in the District of Polwarth, 1857, Death Certificates, Victoria, Nos. 3350, 3351, 3352, 3353, 3354.

[13] L Johnson, An Australian family, vol. 2, Who run beyond the seas, Rock View Press, Camberwell, 1994.

[14] Family recollections of her great-grand-daughter.

[15] PROV, VA 703 Denominational School Board, VPRS 61/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 11, File 57/456, list of subscribers towards the erection of a Catholic Denominational Schoolhouse at Colac.

[16] PROV, VA 919 National School Board, VPRS 880/P0 Inwards Registered Correspondence, Unit 11, Colac, Item 57/774, Report of School Inspector Glen.

[17] PROV, VA 703 Denominational School Board, VPRS 885/P0 Inspectors’ Reports, Unit 2, Item 57/645, Report of School Inspector James Bonwick.

[18] PROV, VPRS 1005/P0 Outward Letter Book (Police Department Geelong), Unit 2, 6 August 1857.

[19] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 54, Item 1858/493, John Pink; Unit 44, Item 1857/651, William Wray.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples