Last updated:

‘Very Serious Doubts: The Case of Hassett and De Le Veilless’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007.

ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Alain Hosking.

The brutal 1889 assault on a Victorian Police Constable, Albert Ernest Vizard, put into motion a sequence of events revealing underlying social tensions in colonial Victoria. Convicted of Vizard’s assault, John Hassett and Francis De Le Veilless would receive the harshest sentence the Crown could apply. Though the guilt of De Le Veilless seemed clear cut, serious doubts about the case against Hassett presented from the outset.

This article tells the story of Hassett’s struggle to clear his name. Making the case for his innocence, Hassett succeeded in rallying the support of his acquaintances in Gippsland, revealing tensions between the rural Victorian community and the authority of the Crown. For a decade from the date of the asssault on Vizard, Hassett would maintain his innocence, backed by his Gippsland supporters and the capable attorney William Forlonge. Despite the determination of Hassett and his supporters to clear his name, and the emergence of new evidence backing their claims, his fate would be resolved in a final desperate act.

On a Saturday night in August 1889, Constable Albert Ernest Vizard walked his beat through the streets of inner-city Melbourne. By morning Vizard would be fighting for his life, bloodied and beaten, the victim of a brutal assault. Within six months, two men accused as the officer’s assailants languished at the Melbourne Gaol, under the highest penalty of the judicial system. Although one of the accused, Francis De Le Veilless, offered little in the way of a defence, serious doubt was brought to bear on the guilt of De Le Veilless’ alleged accomplice, John Hassett. As the case proceeded with the Crown determined to make an example of the two accused, the rural community of Lang Lang, Gippsland, began to close ranks in defence of the young Hassett, revealing an interplay of social tensions in late colonial Victoria. Whilst Albert Vizard would survive his wounds — and the two accused avoid the capital charge — the intersection of their fate on that August night would, nevertheless, resolve itself in tragedy.[1]

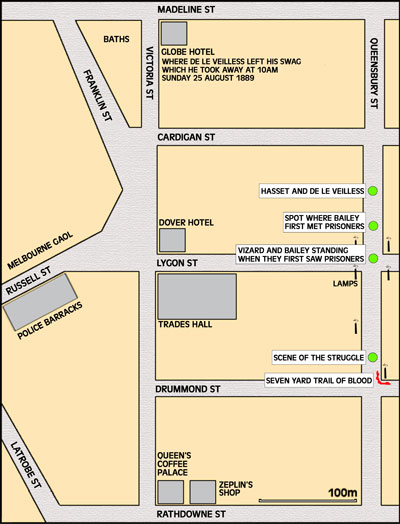

The night of 24 August had begun without event for Constable Vizard, making routine patrols in and around Lygon Street. Over three blocks, Vizard would make his way past the surrounding pubs, shops and houses of Drummond, Cardigan and Queensbury streets, the dim street lamps providing an ambient accompaniment to the hum of social life.[2] Then, at 12.45 am, Vizard was startled by the sound of an altercation. From Lygon Street, Vizard approached the intersection with Queensbury Street, where a familiar face greeted him. It was Patrick Bailey, a young Carlton ironmoulder on good terms with the local authorities. As the two men greeted each other, their attention was drawn westward along Queensbury Street. There, near the intersection with Cardigan Street, the source of the noise which startled Vizard was revealed.

Two men, one short and one of average height, stood in the middle of Queensbury Street ‘growling’ at each other.[3] ‘You’re a bloody cow!’, the short man said. Automatically the Constable approached to intervene. Bailey, too, made his way towards the squabbling men, proceeding somewhat ahead of Vizard. As Bailey passed the men, maintaining his westerly course along Queensbury Street with Vizard behind him, he heard their opening exchange.

Said Vizard, ‘I think you ought to be going home quietly now’.

‘You can go and bugger yourself’, the short man replied.

‘Yes, let him go to buggery’, agreed the taller man.

As the two men continued east towards Drummond Street, one said with sufficient voice to threaten the Constable, ‘If that bloody cow follows us, we will do for him’. Upon hearing this Vizard gave pursuit, reaching the men by the corner of Queensbury and Drummond streets. One of the men turned, saw Vizard approach and declared, ‘Here’s the bugger coming after us! Stand!’

The taller of the two men ran some five yards towards Vizard, raising a belt with a heavy, shiny buckle, over his head. With all his strength, the man brought the buckle crashing against Vizard’s head, sending his helmet flying. Resisting the attack, Vizard drew his baton and brought it against the side of his assailant’s face. ‘Look out, the bugger has split my ear!’, the man cried. Simultaneously, the shorter man pelted Vizard with a barrage of stones and metal, hitting him in the eyes. Vizard focused on the taller man, striking him repeatedly whilst enduring the assault from two sides. But then Vizard slipped when turning. Losing his grip, his baton fell from his hands. In this single motion he managed to maintain his momentum, however, striking the smaller man with his bare fist and knocking him to the ground.[4]

By now the commotion had drawn the attention of Patrick Bailey, who from his position further along Queensbury Street, saw stones come rolling along the footpath. Bailey ran to intercede for Vizard, who noticed his approach. ‘Come quick!’, Vizard pleaded, as he fell under repeated blows from the taller man. Bailey, however, could not come quickly enough, and with a savage blow to Vizard’s skull, the taller man rendered the Constable unconscious. Bailey appealed, ‘You pair of cowards, do you want to kill the man?’

The shorter man, having recovered from Vizard’s blow, now ran at Bailey. Bailey, however, had concealed a weapon, a stick he had acquired on his approach. With this stick he struck the shorter man, who then fell to the ground again, saying, ‘Oh my bloody head’. With Vizard’s body strewn and wrecked in the gutter, Bailey struck at the taller man who called defiantly, ‘We’ll kill this bugger now’. Bailey with his stick, and the taller man with his buckle, laid into each other in an exchange of blows. Then Vizard stirred. ‘Why the bugger’s not dead now’, the taller man observed in surprise and indignation.

Bailey fled, deciding the best course of action was to seek assistance. Meanwhile, the two men pummelled the half-conscious Vizard mercilessly. Signalling a cab near Lygon Street, Bailey set off for the police station, fearing the death of the Constable. As Bailey departed the scene, so too did Vizard’s assailants, who ran down Drummond Street towards Victoria Street. A local machinist, Henry Moore, had heard the assault, and as he approached along Queensbury Street, witnessed the flight of both Bailey and Vizard’s assailants. With early morning quiet restored to the inner-city street, in eerie contrast to the violence of a moment earlier, Moore approached the beaten body of the Constable. Vizard was weak, clinging to life, and covered in blood, balancing against a fence beside the footpath. Moore collected the Constable’s baton and helmet and carried him to the Russell Street police barracks.

The horrific extent of Vizard’s injuries became apparent when he was examined by Francis Drake, a registered medical practitioner at Melbourne Hospital. Drake found four wounds around the eyes and upper head of the Constable, all cut to the bone. At the base of one wound, Vizard’s skull was visibly fractured, with bone fragments penetrating the membranes of the brain. As Drake would later explain, ‘It was necessary to trephine him, i.e. to remove a circular piece of the skull … the size of a shilling’. With this procedure Albert Vizard’s life was saved. He remained at the Melbourne Hospital until 8 October 1889, some six weeks after the attack. By February 1890 he was, by Drake’s estimation, ‘not quite right yet’. For injury to one of its own, the response of the Victorian police force would be swift and determined. Within twenty-four hours of the assault, the first arrest was made.

On the evening of 26 August, Francis De Le Veilless, resembling the description of the shorter assailant, was arrested in Kilmore. De Le Veilless was a South American circus worker of French extraction. He had a long history of larceny, assault, and insulting behaviour (a crime for which he had served fourteen days in prison).[5] Upon his arrest by Sergeant Edward Murphy, De Le Veilless was searched and found to be in possession of a loaded revolver and a blood- stained pocket book, bearing the name of the Globe Hotel, Carlton. With his suspicions reinforced by fresh injuries to De Le Veilless’ head, Murphy took his prisoner to Melbourne for identification. In transit to Melbourne De Le Veilless told Murphy, ‘I’m sorry I did not shoot you. If I had known who you were at the time I would have shot you’.

On 28 August, Patrick Bailey arrived at the Detective Office where De Le Veilless was being held. Without hesitation, Bailey pointed across the room as he entered, stating:

‘That is the man.’

You’ve made a mistake’, De Le Veilless protested.

‘I’ve made no mistake’, Bailey replied. ‘Take off your hat.’

Examining the prisoner’s head Bailey declared:

‘Here is the lump. That’s from my stick, from the blow I gave him.’

‘I’ve no lump’, De Le Veilless maintained.

But further examination by others present confirmed De Le Veilless had injuries fitting Bailey’s account. Furthermore, De Le Veilless’ explanation that he was in Kilmore after leaving Melbourne on the morning of Saturday 24 August was disproved by John Hegan, manager of the Globe Hotel. Hegan swore to personally giving De Le Veilless his swag on Sunday morning. The first of Vizard’s assailants now apprehended, the search for his accomplice was on.

In 1889 John Hassett was twenty-one years old. The young man was held in fair esteem by his employers, having worked in and around Gippsland for three years without trouble. He had also worked for Albert Lynch of North Melbourne, who regarded his character as good.[6] Whilst Hassett had fathered an illegitimate child, he displayed sufficient concern for moral standing and respectability to claim the child’s mother, Mary Redmond, was his wife.

In the eyes of the authorities, however, Hassett had ‘fallen amongst evil companions, and … contracted evil habits’.[7] In January 1888 he received one month’s imprisonment for assaulting a police officer. At midnight on 17 August 1889, the stable of Albert Lynch was burgled, and following his identification as one of the perpetrators, a warrant was issued for his arrest. Avoiding capture for five months, Hassett was eventually arrested by police on 11 December 1889, and as he entered the Carlton watch-house, his troubles deepened. Patrick Bailey was there to identify him as Albert Vizard’s principal assailant.

From the outset, Hassett claimed he was innocent and maintained that he could prove it. Writing from his prison cell, Hassett enjoined John Kennedy, a resident of Lang Lang, Gippsland, to bear witness to his distance from the crime:

My dear friend … I am in great trouble and under lock and key at the Melbourne Gaol. I am blamed for assaulting Constable Vizard in Carlton on the 25th of August 1889 and you and your family know I was not down in Melbourne on that date. You know I was at your place … I might want you to prove my innocence … Mr Kennedy, I am going to be tried on the 17th of February 1890 and I may get a long term of imprisonment and floggings …[8]

Kennedy acceded to the request and made the journey to Melbourne to testify for his young acquaintance. Kennedy did not make the journey alone, however, and as the Supreme Court began hearing the case, a veritable representation of Gippsland constituents turned out to plead for Hassett’s innocence.

PROV, VPRS 515/P0 Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 42, Folio 490 (detail).

Delayed until 26 February 1890, the criminal sittings of ‘Regina versus Hassett and De Le Veilless’ proceeded quickly, and by day’s end, were complete. Brought before Justice ED Holroyd, the two accused faced the charges of ‘wounding with intent to murder’ and ‘wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm’. Vizard took the witness stand first, identifying the prisoners and claiming, ‘I am still suffering from the effects of the wound’. Bailey followed, sure of his identification of Hassett and De Le Veilless, as: ‘The night was starry, not dull nor bright. I could see the two men distinctly’. Francis Drake and Henry Moore also gave their accounts of the great injury done to the police officer.

Unexpectedly, the prosecution widened the scope of criminal activity the accused were alleged to have undertaken. They called the owners of a Rathdowne Street shop. On the night in question, Henry and Ada Zeplin were harassed by two men fitting the appearance of the accused, looking for a man named ‘Skinner’. Evidently, the two men were using this inquiry as a pretext to gain access to the store in order to rob it. The Zeplins’ account, however, relied on an assertion that this harassment had begun early in the evening. The doorman of the neighbouring Queen’s Coffee Palace also reported that the men had been observing the store for days. De Le Veilless could not disprove his involvement in the Zeplin store plot. Witnesses for the defence of John Hassett, however, disproved the possibility of his presence in the preceding days and early evening; he had not been in Melbourne at any of those times.

La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

John Hassett’s defence lawyer, William Forlonge, was thorough and conscientious. Forlonge researched Hassett’s claims to have been in Lang Lang at the time of the assault, and became convinced of his client’s innocence. He summonsed Green Vale contractor Michael Murphy, then Lang Lang farmer John Kennedy, to establish the facts of Hassett’s presence in the Gippsland area on Saturday 24 August 1889. Hassett had been staying on the Kennedys’ property since Wednesday 21 August looking for work in the area. On the Saturday, Kennedy told Hassett of a job that was available at the nearby O’Connor property. In transit to O’Connor’s, Hassett helped unload provisions for Murphy, who saw Hassett departing in the direction of Kennedy’s property, away from the rail route to Melbourne, around 4 pm. The only way Hassett could have arrived in Melbourne was to travel from the Kennedys’ to Drouin station, a journey of fifteen and a half miles along a considerably rough track, in time for the 8.50 pm train. This train arrived in Melbourne at midnight, allowing Hassett forty-five minutes to reach Carlton, become involved in a row with De Le Veilless, and muster the energy after his day of loading, hiking, and travelling to attempt the murder of Albert Vizard.

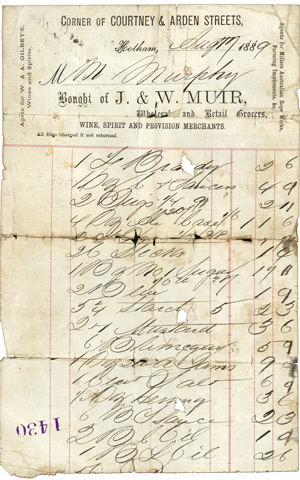

In addition to the testimony of Murphy and Kennedy, Forlonge called a stream of witnesses from Lang Lang and its surrounds, including two of Kennedy’s sons. Each witness concurred with the alibi established for Hassett. Receipts for the goods unloaded by Hassett were entered as exhibits. Three witnesses recalled seeing Hassett in the area ‘on a Sunday’ in late August. And though their testimony was imprecise, it was clearly aimed at fitting the established account, suggesting Hassett’s presence in Gippsland the whole weekend of the assault. Just as the Crown’s determination to prosecute was reflected in the widening of evidence to include the ill-fitting account of the Zeplins, so the determination of the Lang Lang witnesses to come to Hassett’s defence was reflected in their accounts.

Exhibit 1 for the defence of John Hassett, Supreme Court, Melbourne, 26 February 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

However, it seems that the jury was less moved by the details of labour in Lang Lang, than by the horror inflicted on Vizard. Hassett held a prior conviction for assaulting a police officer, and bore a scar across his forehead precisely where Vizard claimed to have struck him. This seemed to present irrefutable evidence for the jurors, who returned promptly from their deliberations with a guilty verdict. Hassett had feared ‘a long term of imprisonment and floggings’, but Justice ED Holroyd was determined to set an example: Hassett and De Le Veilless were sentenced to death.

William Forlonge immediately petitioned for Hassett’s sentence to be commuted.[9] The application of the capital charge in a case of assault was itself unusual, and doubts were bolstered by further written statements from Gippsland residents, asserting Hassett’s innocence. Sent to Gippsland to investigate the uniform defence for Hassett which had emerged from the area, Detective Sergeant J Lomain found community sentiment hardening. John Kennedy informed Lomain, ‘I am now sure beyond the possibility of doubt that Hassett was at my place from the 21st to the 27th of August 1889'.[10] Furthermore, Hassett’s acquaintances were at pains to point out the prior existence of a scar on his forehead. Hassett had claimed the scar was a result of a domestic dispute in which he was struck with a vase. Now Lomain found, ‘Albert Lucas, Mrs Lucas, the two Lynches, Mrs Wilkie and Mary Redmond … all agree he had marks on his forehead, at least eighteen months ago’.[11] Similarly, the O’Connors’ fourteen-year-old daughter recalled eating a meal with Hassett before the weekend of Vizard’s assault, ‘He … had a big long mark over his right eye’.[12]

Further indications of Hassett’s innocence were raised by the inability of the Crown law offices to establish a prior connection between Hassett and De Le Veilless, despite urgent appeals to the police force and prison officials. Nevertheless, the Crown remained determined to impose a harsh sentence. Despite Detective Sergeant Lomain’s assessment that ‘The people whose statements I have given are all of unimpeachable character’, a follow-up investigation, conducted by AP Akehurst, sensed more than a spirit of justice fermenting in the rural east.[13] Reporting four days after Lomain, on 14 March 1890, Akehurst described Gippsland residents as having ‘a characteristic dislike of the police’.[14] Akehurst also arrived at a less favourable determination of Kennedy’s motivations, ‘since he has seen that Hassett’s life is in danger, he, his family, and the O’Connors are all evidently anxious to save it’.[15] This view of the Gippsland people’s evidence as unreliable enabled the conviction to stand, but as there was now serious doubt about Hassett’s guilt the capital charge for both men was commuted to a life sentence.

Photograph © Alain Hosking 2006.

During the subsequent decade, William Forlonge maintained his faith in Hassett’s innocence, petitioning at every opportunity, exposing the contradictions of the Crown’s case. With each appeal Hassett’s hopes were raised, only to be dashed by rejection on the basis of his having possibly reached Melbourne by train. These rejections strained Hassett’s health; by 1900, aged thirty-one, he resided as a dispenser in Geelong Gaol, suffering from a heart condition.[16]

On 24 March 1900 Forlonge wrote to Sir John Wadden, Lieutenant Governor of Victoria with a plea for Hassett’s release on the basis of time served. Citing the case of another convict, whose recent death sentence had been commuted to ten years, Forlonge emphasised the exceptionally harsh treatment of his client:

… during the last ten or eleven years in which I have been associated with criminal proceedings … I cannot call to mind any case … other than wilful murder, in which the Executive in commuting the death sentence has ordered that the prisoner … should be imprisoned for life.[17]

Hassett, too, had a new article of proof. In his ten years behind bars he had crafted an eloquent style of legal writing and conducted his own investigations into the methods of the police. Writing from his cell at Geelong, Hassett pointed out, ‘the Police Gazette, for the 21st August 1889 contains a description of my person, as wanted from the 17th August [prior to Vizard’s assault] among my other personalities … is mentioned my scarred forehead’.[18] But this revelation failed to impress prison authorities, who maintained the integrity of his sentence.

Hassett lost all hope. On 6 December 1901, having managed to smuggle a quantity of poison into his cell, Hassett ended his own life. On 27 December The Herald carried the headlines:

POSSIBLY INNOCENT

CONVICT JOHN HASSETT

A REMARKABLE CASE

A CRIME OF THE EIGHTIES

VERY SERIOUS DOUBTS[19]

The Herald article revealed a growing body of opinion amongst the legal profession that Hassett was innocent. Most disturbingly, the article suggested inquiries within ‘the criminal class’ had revealed not only an underground cognisance of Hassett’s innocence, but the name of the man who had in fact been De Le Veilless’ accomplice, the main perpetrator of the assault.[20]

Innocent or not, John Hassett’s life was the price of an example set to ‘the criminal class’ and the wider society. That this example must have seemed monolithic to Hassett at the time of his suicide is evident; his decision was taken in spite of eligibility for parole in 1908.[21] With this last desperate action, however, Hassett did succeed in securing a kind of posthumous justice. Whilst The Herald investigation arrived too late to relieve his suffering, its publication focused public attention on his likely innocence. In doing so, the final chapter of a late-colonial controversy, begun on a fateful night in 1889, was brought to its conclusion.

Endnotes

[1] All events and character dialogue, unless otherwise footnoted, are sourced from PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett, and from ED Holroyd, Report of criminal sittings of the Supreme Court, 26 February 1890, to the Attorney General, Judges’ Chambers, Melbourne, 5 March 1890.

[2] A deduction based on the proximity and density of public hotels, and the thin spread of street lamps, as mapped in FO Borsom, Report on the assault of Constable Albert Ernest Vizard, Carlton Police Station, Melbourne, 13 March 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[3] The description of the men as ‘growling’ is Patrick Bailey’s, from the 26 February trial of Hassett and De Le Veilless.

[4] This is my interpretation as Vizard described the two actions in a single sentence at the trial of Hassett and De Le Veilless.

[5] T Sadlier, Report in reference to the previous history of John Hassett and Francis De Le Viellis [sic], Police Department, Superintendent’s Office, Melbourne, 3 March 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] John Hassett, Letter From Melbourne Gaol, Melbourne, 9 January 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[9] William P Forlonge, Petition on behalf of John Hassett, Salisbury Buildings, Bourke Street, Melbourne, 24 March 1900, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett,.

[10] J Lomain, Report on petitions on behalf of John Hassett by residents of Gippsland, Police Department, Melbourne, 10 March 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] AP Akehurst, Report on enquiries made at Lang Lang, Yannathan and Surrounds, Melbourne, 14 March 1890, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] William P Forlonge, Petition on behalf of John Hassett, Salisbury Buildings, Bourke Street, Melbourne, 24 March 1900, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett,.

[17] ibid.

[18] John Hassett, Letter From Geelong Gaol, 28 February 1901, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

[19] Herald, Melbourne, 27 December 1901.

[20] ibid.

[21] Penal and Gaols Department, Indent of No. 23803 John Hassett, Geelong Gaol, 10 October 1900, PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 17, Francis De Le Veilless/John Hassett.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples