Last updated:

‘“The Township is a Rising One”: The growth of the town of Loch and its school’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lyn Payne.

The township of Loch in South Gippsland was established with the coming of the railway in the 1880s. Early in Loch’s development, the townspeople recognised the need for a local and accessible school to provide the fluctuating numbers of children with an elementary and socialising education. Petitions were sent to the Victorian Department of Education for this purpose and by 1889 the school had been constructed and a Head Teacher, Francis William Clarke, appointed. He remained at Loch for the next 28 years and his time there provides the focus for a broad exploration into the establishment and growth of a small Victorian town. The school’s fluctuating numbers reflect the transient nature of Loch’s early population, while Clarke’s experiences with the Victorian Department of Education demonstrate the difficulties of dealing with a remote and officious bureaucracy. In many ways the history of this school and its teacher provide valuable information about living in what was then an isolated town, and the efforts of its residents to establish a sense of place and community. Through school history, we gain insight into the values, aspirations and achievements of the town’s people.

Beginnings and Sources

For this article, the author mainly utilised VPRS 640 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence 1878-1962 and VPRS 795 Building Files: Primary Schools 1863-1975. To open a box at PROV and take out the fragile records of Loch State School is to enter a world as familiar and foreign as the moon, yet these events took place only three generations ago. It is a world of deprivation and hardship, of deference and pride, of religion and manners, of isolation and sometimes of danger, of uncertainty and also of hope and optimism, a world where it can be said ‘the township is a rising one …’[1]

We bought our farm at Loch, a small township in South Gippsland, in 1982 and shortly after its purchase I embarked on research for a thesis based on the history of education in Victoria. For a major piece of work, I chose to write a history of the Loch State School and subsequently embarked on many visits to Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), then based in Laverton, to peruse the Victorian Department of Education’s primary school records. I found a wealth of letters, receipts, marginalia, scribbled notes, petitions, reports and attendance records that contained the names and signatures of early European settlers already familiar to me through the street, track and laneway names of Loch and its surrounds. These were people who cleared and settled the land carved from an early pastoral run, the Kangaroo Run, itself formed by arbitrary boundaries imposed on the steeply forested hills and gullies of the lands of the Indigenous Bunerong people.[2] I also delved locally and found published oral histories, recorded reminiscences, newspaper articles and a photograph of the school obtained through a somewhat clandestine loan. I was fortunate to be able to interview a local resident who had attended Loch primary school in 1906. I found many of Loch’s first citizens, with whom I had developed familiarity, in the cemetery at Nyora and some in Poowong. I discovered our farm formed part of a parcel of land pegged out by Mary Henrietta Leys, the first Head Teacher at Jeetho West. I felt personally located in the early days of this small Victorian township that owed its establishment to a fortuitous change in plans for the route of the Great Southern Railway when it was decided to utilise the easier gradients of the valley of Alsop’s Creek through Loch and Bena rather than follow a ridge of hills through Poowong to Korumburra.

Recently I revisited this work and again appreciated the broad application of school records for the historian. They not only document the day to day concerns of bureaucrats, students and teachers, but contain a wealth of sources that illuminate broader personal and community aspirations, social and religious values, institutional and bureaucratic activity (and inertia), class structures and issues of gender, attitudes to power and authority, community health issues, and attitudes to the environment. My research using the state archives at PROV provided me with information on what it was like in a difficult environment with a harsh climate, isolation, primitive facilities and lack of infrastructure. It also enabled me to come to some understanding of life in a small township in the late nineteenth century, its social composition of European pioneering families, community leaders, ambitious professionals, canny speculators, workingmen and itinerant travellers; and their personal aspirations, concerns, ambitions, achievements and disappointments. I have reworked my earlier writing to encompass this broader perspective.

Photograph courtesy of Loch & District Historical Group.

The Township

Motorists on the South Gippsland Highway, travelling through the usually green and pleasant hills to Korumburra, Leongatha, Wilson’s Promontory and on to Yarram, will pass the turn-off to Nyora and then swing left on a bypass road that skirts the edge of the small township of Loch. If they glance to the right on this swift journey, they may notice a small railway station, a hotel, an old bank and a post office. They will be well past, and will not see, Loch’s small primary school, situated on a gentle rise on the curve of the old highway that is now a quiet side route into the township. The school’s position was considered ‘a fine one’ in 1888 when protracted negotiations took place for the purchase of land. It was then on the main road into the town, opposite land later provided for St Vincent’s Roman Catholic Church. For a century, then, those two civilizing influences, church and school, formed a gateway into the town. The original school building with quarters has long disappeared but a ‘new’ building of 1892 and a companion building erected in 1910 are still visible though now obscured by the later addition of a 1965 extension which spans the northern elevation of the school.

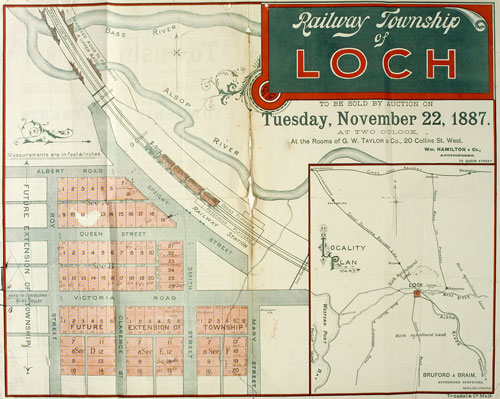

In the 1880s, the roads were little more than pack horse and bullock tracks, winding through almost impenetrable forests of blue and white gum, messmate, hazel and blackwood, fronded by enormous tree ferns and variously described as the Great Gippsland Forest, the primeval forest or, more simply, ‘the Big Scrub’.[3] The Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp was then impassable for bullock teams and drays, and European settlers pushed southwards from Drouin and Poowong, or east from Westernport and Grantville, to take up land in the pastoral leases and peg out their own allotments under the 1869 Land Act. To canny landowners, it seemed probable the population would grow with the construction of a rail link, the Great Southern Railway, from Dandenong to Yarram. The first section of the line to Whitelaw’s Track near present Korumburra commenced in 1887 and reached Loch in late 1890.[4] Early in the 1880s land speculators began buying up allotments along the proposed route, to be surveyed and subdivided into townships. One of these was the property of Augustus Robert Smith situated in the Parish of Jeetho at the junction of the Bass River and Alsop’s Creek, an area then variously known as Sunnyside, Jeetho or Poowong. The first sale of town lots in what was to become Loch, then described as the ‘principal township on the first section of the Great Southern Line’, was held in November 1887.[5] As the railway approached, the town swelled to accommodate a tent city of railway gangers and their families who joined farmers, croppers, speculators, storekeepers, professionals and craftspeople in a thriving and optimistic community.[6]

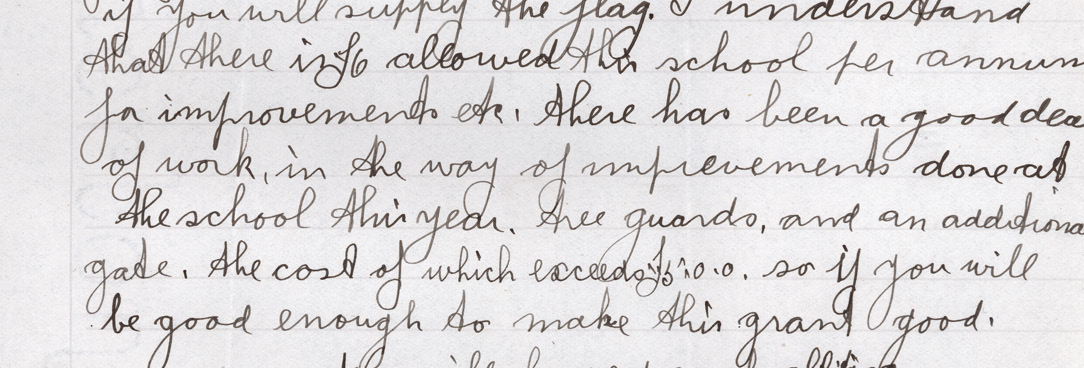

PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

The nearest school was at Jeetho West where the head teacher was Mary Henrietta Leys. With her father, she had pegged out a Crown Allotment south of Loch in 1876 and rode on her father’s horse four miles to her duties each day along the rough bush tracks.[7] She remained at Jeetho West until 1889, shortly before the closure of the school in 1900, and was to prove so able and popular that two petitions were sent to the Education Department on her behalf, one for her to remain at Jeetho West after the destruction of the school by fire, and another later request that she be appointed to the new school at Loch, ‘on account of the very large proportion in number of female over male pupils eligible for instruction at the present time …’[8]

Jeetho West, or Sunnyside as it was sometimes designated, was a long and difficult journey for the children of Loch, the roads often being impassable in the winter rains. According to Inspector Hamilton, sent to visit and report on the viability of a school at Loch, his view of Jeetho West was that many children ‘… do not attend that school, nor do they attend any other because of the character of the roads’.[9]

Photograph courtesy of Loch & District Historical Group.

In March 1887 a petition requesting the establishment of a school in Loch was sent to the Minister for Education. Most of the signatories’ names appear on early maps of the district for they were among the earliest European settlers of the Loch and Jeetho area.[10] Mr AR Smith placed an attractive site aside for educational purposes to be considered by the Department of Education, as the people of Loch feared their children were running wild for want of education and discipline. They were described as a rough and unruly lot ‘running in a half semi [sic] state of wildness for want of teaching’. Indeed, one good citizen believed that only a male teacher would be able to manage such boisterous rascals, ‘… a female would never do here as there are three boys who will be sent to the school who would put her out the first week … I am naturally anxious that a teacher of the sterner sort should be appointed who will be able to put on the iron hand if required’.[11]

The Department responded by sending Inspectors Craig and Robertson to visit Loch to assess the numbers of children who would be in attendance and to report on the viability of a school there. They were hesitant about establishing another school while that at Jeetho West was available, fearing that two schools in the vicinity would be unsustainable. Their reports therefore were unfavourable to a new school. At once, the petitioners protested that their children could not continue to travel the distance to the school at Jeetho West for ‘it is no joke to saddle two or three horses every morning for a ride of four or five miles as has been the case these last eight years’.[12] Subsequently, in December 1887, Inspector Hamilton provided the names of 44 children who possibly would be in attendance. Following this report, negotiations began with Mr AR Smith for the purchase of a site suitable for a school.

Smith’s ensuing protracted negotiations with the Department show not only his own determination and entrepreneurial skills, but the inertia, tardiness and parsimony of a Department that could not decide on the choice of a site or the purchase price. Smith furnished maps, sketches and advertising material in an attempt to convince them they were getting a good deal. He wrote: ‘I have made the price as reasonable as possible and I think you will say so when you see the prices the lots brought in the same street … I have marked £200 per acre and giving the quarter-acre as promised’. The hesitancy of the Department contributed to a growing sense of urgency and frustration from the townspeople. Suggestions were made by some parents that they would erect a suitable building themselves, to be let ‘at a nominal rent’. ‘They are getting very dissatisfied’, wrote Smith, ‘and partly blame me for it’.[13]

The reports of inspectors and departmental minutes indicate awareness of an increase in population and the growing urgency for a school in Loch, noted as an ‘absolute necessity as soon as the railway is completed’. In March 1888 Inspector Craig estimated an attendance of twenty children, recommended that the Department accept Smith’s offer of Site B on the map, ‘a splendid site’, advocated the purchase of three quarters of an acre and acceptance of Smith’s gift of a further quarter acre, suggested the usual portable school with dwelling attached be sent before the winter rains and recommended this should be transported by boat to Grantville and thence to Loch by carriage.[14]

Even with such firm advocacy, the Department failed to act and frustrating delays continued. Over time, the number of children increased and the bureaucrats passed on. Robert Lowe wrote to the Minister:

It is now over twelve months since our application for a school was made for Loch, and during that time, there has been no less than three inspections reported on the matter. And from anything we know to the contrary, these reports have been favourable.

Since the last report our children of school ages have increased considerably.

We must try to draw your attention to the almost impassable state of our roads during the winter months and if it is your intention to grant us school it should be sent at once. A site has been given and the late Inspector Craig considered the site a desirable one.

If it is not the intention to send a school kindly let us know at once so that we may erect a suitable building and rent same to your department.[15]

‘If the residents will put up a suitable building in a central position and lease it at a moderate rental to the department,’ was the smooth rejoinder, ‘the establishment of a school … will be greatly facilitated’.[16] Finally, a decision from the Board of Advice settled the matter when it approved the proposed site and emphasised the likelihood of continuous growth in the population of the township. By 18 May 1888, authority was given to accept Smith’s offer of an acre of land at 150 pounds. Tenders were invited to clear the site and three local citizens, W Burns, F Wells and R Laver, offered to complete this work. A departmental memo shows tenders were accepted and a portable building with quarters was despatched on 12 October. Four months later, on 21 January 1889, the final certificate of completion was given.[17]

Photograph courtesy of Loch & District Historical Group.

The Head Teacher

The frustration and delays were not over for the parents of Loch for although they now had a school, as yet there was no teacher. ‘I have been requested by some of the families of this place to ask you the reason that the school at this place has been erected for at least six weeks and everything in readiness but there has as yet been no teacher sent up’ wrote Mr Wadeson on 19 February 1889.[18] The following day the Department received the petition mentioned earlier, signed by twenty parents requesting that a lady teacher, Miss Mary Leys, ‘who is well known and appreciated by your petitioners’, be appointed to the school in Loch. In reply, the Department noted that it was required to nominate the first teacher available for such an appointment, male or female. The familiar and popular Mary Leys was passed over in favour of Francis William Clarke, a teacher then employed in the Relieving Service.[19]

When Clarke was appointed to his position at Loch, he was 31 years old and had extensive experience in both large and small urban and rural schools. He had served his apprenticeship in farming and pastoral communities and on the goldfields. He was described as intelligent and efficient and was also qualified to teach Military Drill. He must have been well-acquainted with similar conditions to those which awaited him at Loch and the liveliness of the local youngsters would have been no better or worse than others he had encountered in his career. Clarke was experienced, but obviously enjoyed his mobility and his salary as a relieving teacher. He did not wish to come to Loch.

Initially he received his new appointment with equanimity. On 15 January 1889 he courteously replied that he was ready to take up his position as soon as he was relieved at the school in Aberfeldy. On 20 February 1889, just seven weeks later and on the same day the parents of Loch petitioned the Department for the appointment of Mary Leys, Clarke wrote to the Department requesting that he be granted permission to remain on the Permanent Relieving Staff. He was willing, he said, to take up his appointment to Loch after a period of one and a half years. He was probably relying on an increase in school attendance with Loch’s steady growth and completion of the proposed railway. Certainly he gave a considerable loss in salary as his reason for wishing to delay his appointment. ‘My chief concern is that I shall lose considerably in salary at present by going there.’ Perhaps he also enjoyed his mobility as a relieving teacher. ‘I shall probably be locked up long enough at Loch’, he quipped. He requested the Department to ‘send some other teacher there, temporary, for above time as it is not very far from town’. His request was refused and Loch State School no. 2912 opened on 1 April 1889 with Francis William Clarke as Head Teacher.[20]

The School

From the day of opening Clarke was plagued by a lack of facilities and fluctuating attendances. ‘I have the honour to report that I opened the above school this morning with 16 children’ he wrote on 1 April. ‘No books, slates, maps or requisites are here at present.’ On the same day he notified the Department that one tank was already useless, that one of the outhouses had a spectacular lean from the perpendicular and in the first strong wind would very likely be blown over, that neither the school nor residence porches were floored and that both buildings required scrubbing. A week later he requested an Inspectors’ and School Register and a notation frame and enquired about the proposed rental for the school residence. This was set at 4 pounds per annum. By 12 April, Clarke was also complaining about the state of the school grounds and requesting the erection of a fence, as ‘the cattle in the paddock surrounding the school congregate round the building at night and Mr AR Smith from whom the site was purchased is constantly afraid of losing cattle’. Clarke later reported that both tanks were useless and the cattle were sheltering in his porch.[21]

By the end of March 1890, there were 52 children on the roll and Clarke reported an average attendance of 39. True to earlier departmental fears, as the attendance at Loch grew, that at Jeetho West steadily declined. In September of the previous year, the then Head Teacher, Grace Hall, had written anxiously to the Department over a report she had read in a local newspaper about the proposed closure of the school. ‘I beg to state that as soon as the weather clears and improves there will be seven additional scholars who are prevented attending at present owing to the bad state of the roads.’[22] While Grace Hall was anxiously contemplating the decline of her school, Clarke had 49 children on the roll and was making application for an extra staff member, a sewing mistress, to be appointed to Loch. After a competitive examination, Mary Ann Taylor, the sister-in-law of AR Smith, took up her duties at the school where she also took the infants’ or babies’ classes in the afternoons.[23]

Despite increasing growth, the population of Loch was a variable one due to the movement of the navvies or railway workers who followed the line as work on the railway progressed. The families of these itinerant workers moved into the town and then moved on with the railway, causing fluctuations in the numbers of children attending the school and general instability in the classrooms. The quality of scholarship was adversely affected, an important concern when teachers were paid by results. Clarke noted the constant changes and the adverse effects on his pupils. Of the 80 children registered since the school’s opening, only 40 remained by November 1890, the other half having left the district. Of those remaining, only half had been with him since the school opened and because of delays in opening the school a number of his students were above the average age for their class. In addition, many of the children did not attend regularly. Clarke requested that the Department take action and the examinations (on which his salary would be based) be deferred. His request, of course, was not granted.[24]

At this stage Clarke was contemplating marriage and on 22 December 1890 he began a long correspondence with the Department over the conditions of the residence attached to the school. His initial request was for minor improvements to make the quarters more habitable, for improved ventilation in both the school and residence, and for varnishing the two rooms which would constitute his new abode. ‘I intend to reside in the rooms. At present they are miserable and bare but would look a little better being varnished.’ By 26 January 1891, perhaps with a view to accommodating his future sister-in-law who later resided with the family, he requested permission to build a small detached building in the school grounds, ‘about twelve feet by ten feet (or larger) … of soft wood, iron roofing with a brick chimney’. This request, accompanied by a helpful sketch, was granted. Four days later Clarke discarded that idea and made the first of his many requests for the Department to provide additional quarters. Disarmingly, he phrased his request with the welfare of the children in mind and appealed to the economic sensibility of the Department. The most efficient solution, he thought, was by using the whole of the present building as a school by simply cutting two doorways into the room, and erecting a new four-roomed detached residence:

The latter I am strongly of opinion would be the cheapest and best as if the township increases as it is thought it will, a building put up now would require to be altered in two or three years, whereas the whole of this building would do for a longer period, and a more suitable building could be erected when required.[25]

His suggestion would be considered, replied the Department, although ‘in view of the more pressing demands upon the Department’s resources it may be some time before the work … could be proceeded with’. The economic stringencies of the 1890s were already apparent.

One month later, on 20 February 1891, Clarke was married to Annie McGuire in the Church of England in Loch. Witnesses at his marriage were Augustus Smith and AG Taylor. His friendship with the respected Smith and Taylor families indicates that Clarke was well accepted in the township and occupied a position of some social standing.

He continued to press for suitable accommodation for himself and his bride, couched in terms of providing extra accommodation for his students. His concerns appear to be genuine enough. Forty to forty-five children were often present, he wrote, there being ‘only accommodation for about thirty’. He drew attention to considerations of health. ‘Several of the children have lately gone home from the morning meeting ill, owing I believe to the above cause.’ He also referred to the predicted growth of both the township and the school population. ‘I think there is very little doubt of there being a good school here.’ But the quarters were cramped and uncomfortable and the erection of a new residence would, he believed, solve both these problems:

… there are only two rooms in the quarters, one small, which are not at all pleasant or comfortable to live in … I would therefore earnestly request that a four-roomed cottage be erected at once, before the winter comes on and the present building be used as a school.[26]

Although this plan received approval from at least one inspector, departmental notes indicate that an alternative plan was adopted, that of converting the schoolroom into additional quarters and erecting a new school building.[27]

Clarke made arrangements for the school to be temporarily accommodated in the Sunday School Hall of the Church of England while the building works were taking place. He busied himself with advice to the Department as to how he would like the school converted to quarters. The schoolroom itself, he wrote, should be partitioned into two rooms. A double brick chimney should be provided as the old one smoked badly. Two nice mantelpieces should be provided to complete the fireplaces, while the windows should be lowered about one foot and cleaned of their paint. The interior should be stained and varnished, the whole completed by a verandah on the north side to keep out the afternoon glare.[28] It is doubtful that all of Clarke’s requests were complied with but by 2 November 1891 a contract had been let for the conversion of the school into a residence of four rooms. This was completed by 2 December 1891 and was then let to Clarke at a rental of 9 pounds per annum. The newly constructed schoolroom had accommodation for 54 pupils and was built at a cost of 230 pounds. It appears that the school building was not completed until late June of the following year as the Sunday School premises were not vacated until 25 June 1892.[29]

By 1901 the Clarke family had grown, ‘We are eight, self, wife, five children and wife’s sister,’ and accommodation once again became a pressing matter. In July of that year Clarke requested that the residence be revarnished as it had not been touched for nine years, and an extra bedroom be added ‘for the preservation of good health’. In the space of one week he doubled his request. ‘Five sleep in one bedroom, three in the other, which are not very large and as the elder ones are growing up, we could do with more rooms. We could easily do with a couple.’ The quarters were desperately short of facilities for his large family, for there was no wash house or bathroom and there were not enough bedrooms. He eagerly sought an estimate of the cost of two extra rooms and sent this off to the Department. By February 1902 he moderated his demands. ‘I have the honour to request that I may be informed if there is any possible (probable) hope of getting two additional rooms (or one) added to the dwelling and when … I will be thankful with one bedroom.’[30] Nine months later the Department, preoccupied with its own economic problems, again refused Clarke’s urgent requests: ‘… in view of the state of the finances, the money at the disposal of the Department can only be devoted to repairs of an urgent character. The question of erecting additional accommodation at the residence must therefore remain in abeyance’.[31] Clarke then took matters into his own hands. In 1899 he had bought a three-acre paddock adjoining the school on the western side from the estate of Christie Thomas Smart. Mr Shackleford, who had been an architect, designed a residence for him that was built at a cost of 400 pounds between December 1902 and June 1903.[32]

The wheels of bureaucracy were still moving although very slowly indeed. On 30 November 1904, almost two years later, a departmental recommendation authorising 174 pounds to be spent on additions to the old residence was approved and noted on the back of a letter Clarke had penned on 21 February 1902. We can only sympathise with Clarke’s despair at the snail-like bureaucratic process. ‘I reported two years ago that I did not now require an addition to the residence,’ he replied. ‘I have built a house of my own.’ The authorisation was promptly withdrawn.[33]

Letting the school residence to cover his own financial obligation to the Department was now a major problem for Clarke, for the Department was prepared to continue deducting money for rent for a building he no longer occupied. His tenants appear to have been temporary and short term, and often late with the rent. To exacerbate matters, the Department maintained that he owed some 12 pounds in arrears. ‘I have not received the rent I pay for it’ Clarke pleaded in Sept 1905. ‘I have paid from £50 for quarters which I have not used.’ In November of that year he appealed to the Department to remove the dwelling: ‘… the letter I received has caused me to be unwell all the week through sleeplessness and worry … Can the Department take over this place or better still remove or will they sell?’ For the Department, his pleas were in vain. ‘This is the usual charge whether the quarters are occupied by Head Teacher or not occupied’, they noted. By February 1906, Clarke’s correspondence took on a more desperate note. ‘You have deducted from my last salary more than the amount I have received.’ ‘There does not appear to be any need for a reply’, was the unfeeling rejoinder.[34]

Photograph courtesy of Loch & District Historical Group.

Attendance figures at the school reflected a steady increase in the population of the township. By June 1906, attendance had risen to 74 children, 28 of them infants. Clarke wrote to the Department with a solution that would not only solve his problem with the letting of the residence, but would alleviate the crowded conditions of the school. ‘I can easily get over the difficulty for the present by using the school residence for the infant classes if I get permission to do so.’ By July of that year Clarke was relieved of the responsibility of paying rent when the Department finally acknowledged the quarters provided were inadequate for his family. He was expected, however, to carry on the general oversight and care of the buildings and to arrange for the letting of the quarters at a rental which was fixed at five shillings.[35]

Clarke’s request for more room for infants’ lessons at least urged the Department to look into the crowded conditions of the school. They found the existing accommodation was hardly adequate and consideration was given to building a new school, although the projected cost of 300 pounds was subsequently thought to be too high. Rather than put the infants into the residence, a decision was taken to lengthen the existing building. Authorisation was therefore given to extend the existing schoolroom, to remove the gallery which was considered a hindrance, to provide cloakrooms, improve ventilation and carry out repairs. This approval was given in July 1907. By 1910 attendances had further risen and an extra schoolroom was added. These are the two rooms which exist today.[36]

Clarke was remembered as a stern disciplinarian and he no doubt exercised the techniques of a nineteenth-century pedagogue to achieve educational and social outcomes. The children were marched military style into school each Monday morning then marched down the main street of Loch and back. They were marched to the river banks where they lined up to sing. The syllabus included writing, arithmetic, geography and lots of dictation. Mental arithmetic was held in the open air. Despite his authoritarian manner Clarke was described as having been a good teacher and reports from inspectors describe him as having a good natural ability in teaching and of maintaining good to excellent discipline throughout the school. It can be safely assumed that the people of Loch would have approved.[37]

Clarke’s correspondence often provides a personal response to some of the crises that befell the town, the most notable being the great bushfires of 1889:

… there is grave danger of this school and dwelling being burnt by the bush fires. There are a dozen houses burnt within a radius of ten miles, five within a radius of three miles. The fires are burning on every side of the township … If a South or West wind comes, we will have a bad time, as the place is surrounded by big timber … I have sent Mrs Clarke and family away, packed or buried portables and most of the townspeople have done the latter.[38]

Clarke was always conscious of the health of the children, as well as that of his own family, due to overcrowding, poor sanitation and lack of hygienic conditions. He was appalled, for example, at the lack of proper heating in the Sunday School building when children had to sit in damp clothing.[39] He appears to have worked tirelessly in the school grounds, carrying out repairs and maintenance. He reported on one occasion a nest of snakes under the school building and was advised by the Department to coax them out with milk and then shoot them, being careful, of course, not to damage the building.[40] Clarke also participated in the community and sporting life of the town, having some prowess as a sportsman. In 1903 he was secretary, treasurer and captain of the Loch Tennis Club and from 1889 to 1890 he was president of the local football club.[41]

The Legacy

Loch today is a thriving town but it has completely changed in recent decades. Some families with familiar names still reside in the town but where there was a butcher there is a real estate agent, where there was a store there is a quilting workshop, the health centre is a café, the bank an antique shop, the blacksmith’s was a junk shop and is now a private home. It is not possible to buy food staples, go to the bank, or purchase a hammer. A car is necessary now to travel to Korumburra or to Cranbourne to purchase such things. The ever-widening South Gippsland Highway snakes smoothly over the once impassable Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp. Melbourne is an hour away.

Photograph courtesy of Loch & District Historical Group.

The school is still there but Francis Clarke’s residence was taken away some ten years ago to begin life anew in a different community. The once rough tracks are paved and the scrub, the big timber, has long disappeared, as have the blackfish in the Bass River and in Alsop’s Creek. The Great South Gippsland Railway is a novelty train, running on weekends from Nyora to Korumburra for the entertainment of tourists. Even the station has gone. Loch seems now a township offering pleasant respite for the traveller — but one on the way to somewhere else. Nevertheless, the school is a thriving one and celebrated its centenary along with that of St Pauls Church of England and Loch Football Club in 1989. In 2001 its enrolment of 80 children was drawn from the town and from small subdivisions and farms, with approximately half of the children travelling to school by bus. In that same year the township of Loch celebrated its own 125th birthday with a book to complement the earlier history of the region The Land of the Lyrebird.[42] Entitled Loch & District 2001, …From then until now, the aim of the book was to enable future generations to ‘proudly carry on … and to ensure that this beautiful part of South Gippsland never loses its identity … In this way we leave our footprints – however faint – to show that we have passed this way. In another 125 years we too will be history’.[43]

Endnotes

[1] Report of Inspector Dennant, Victorian Department of Education, 6 April 1891, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[2] G Presland, The land of the Kulin, Mcphee Gribble, Australia 1985, pp. 24, 50. Evidence of Indigenous occupation is mentioned by early European settlers in The land of the lyrebird: a story of early settlement in the great forest of South Gippsland, The Shire of Korumburra for the South Gippsland Development League, 1972, p. 31. TJ Coverdale, for example, writes of evidence of intentional burning of the scrub, of stone tomahawks lying on the surface and the discovery of clay ovens in the dense bush.

[3] TJ Coverdale, ‘The scrub’ and WHC Holmes ‘Scrub cutting’, in The land of the lyrebird, pp. 16-33 and pp. 54-66.

[4] RJ Fuller, ‘The great southern railway’, in The land of the lyrebird, pp. 221-29. For a complete history of the rail line see KM Bowden, The great southern railway, Hodges & Bell, Maryborough, 1970.

[5] Joseph White, The History of Loch & District, M&B Print, Korumburra, 1972, pp. 3-7. A full advertising brochure with date, time and place of sale, and attractive description of Loch and surrounds is held by PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912. See also the reminiscences of Mrs AR Smith in The land of the lyrebird, pp. 198-201.

[6] The variety of townspeople and the important skills they brought with them to establish a successful new settlement are described in White, The history of Loch, pp. 3-7.

[7] Letter from Mary Leys to the Department of Education, 30 May 1887, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1396, Loch State School 2912. See also report by Inspector Carmichael, 30 April 1885, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1396, Loch State School 2912.

[8] Petitions of 20 June 1881 and 20 February 1889. Petitioners’ names include those of Ferrier, Greening, Horner, Loh, Bowcher and Wadeson. PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912.

[9] Report of Inspector Hamilton on the viability of a school in Loch, 17 December 1887, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[10] Petition of 14 March 1887. The return address is given as Sunnyside via Lang Lang. The names on the petition include Messrs Laver, McTaggart, Ferrier, Loh, Morgan, Simpson, Wells, Taylor and Greening. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1679, Loch State School 2912.

[11] Letters from D Wadeson to Department, 25 April 1888, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912; and W Bowcher to Department, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912. In fairness to the people of Loch, the same three boys had been expelled earlier from an urban school, ‘for stoning the master at his desk’.

[12] Reports of Inspector John Robertson 5 July and 19 August 1887 and letter from David Ferrier, 6 March 1888, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912. Ferrier gives his address as Poowong via Drouin in this correspondence.

[13] Letters from AR Smith to Inspector Hamilton and Department, 14 January, 21 January, 26 January and 15 March, 1888, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[14] Inspector Craig, minute dated 20 March 1888, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[15] Letter from Robert Lowe to Department of Education, 25 April 1888, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[16] Department of Education, departmental minute, 25 April 1888, PROV, VPRS795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[17] Authority to establish a school and purchase land was gained from Board of Advice 12 May 1888 and noted in Inspector’s Report 18 May 1888. A contract for the purchase of land from AR Smith is noted in Crown Solicitor’s Office memorandum 17 September 1888. The despatch of a school and quarters is contained in a Departmental memorandum 1 October 1888. Receipts for land clearing are dated 16 and 18 October 1888 and the final certificate of completion is noted in a Departmental report 21 January 1889. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[18] Letter from D Wadeson to Department of Education, 19 February 1889, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912.

[19] Departmental response to petition requesting Mary Leys appointment, 29 March 1889, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[20] Letter of acceptance from Clarke to the Department, 15 January 1889. He requested he remain on the Relieving Staff on 20 February 1889. PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912.

[21] Letter from Clarke to the Department, 1 April 1889. His problems with tanks, outhouses, and cattle are in letters of 8 April and 8 July 1889, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912.

[22] Letter from Grace Hall to the Department, 3 September 1889, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1396, Loch State School 2912.

[23] Letter from Clarke to the Department, 28 February 1890. Clarke expressly favoured the younger candidate, Eva Bowcher, over Miss Taylor. The examination included dictation, arithmetic, parsing, geography and spelling as well as needlework. PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 506, Loch State School 2912. Recollections of infants’ and babies’ classes are contained in ‘Mrs R Horner’, White, The history of Loch, pp. 57-8 and in information given to the author by Mrs Annie Hee (nee Cowcher) of Loch.

[24] Letter from Clarke to the Department, 20 December 1889, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 516, Loch State School 2912.

[25] Letters from Clarke to the Department, 22 December 1890 and 26 January 1891, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[26] Letter from Clarke to the Department, 23 March 1891, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[27] ibid. The approval of a plan put forward by Inspector Dennant is in a Departmental minute of 6 April 1891, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[28] Letters from Clarke to the Department, 16 April, 26 May and 27 July 1891, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[29] Letting the contract for conversion of the school building into a residence is noted in a Departmental minute 2 November 1891. The final certificate of completion of the dwelling was reported by Inspector Cook, 2 December 1891 and letter from CS Bigelow 20 July 1892. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[30] Letters from Clarke to the Department, 24 July, 1 August, 2 September 1901 and 21 February 1902, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[31] Departmental minute, 24 November 1902, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[32] See White, The history of Loch, p. 82 for information about Clarke’s purchase of land and p. 15 for the residence he built. Details of Clarke’s living conditions are given in a letter from him to Frank Tate, Director of Education, 25 May 1906, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[33] Authorisation and allocation of money for additions are noted in a minute of 30 November 1904. For Clarke’s response, letter to the Department 8 December 1904. Withdrawal of the offer is noted in a minute of 22 December 1904. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[34] Letters from Clarke to Department, 13 December 1904, 5 June, 25 September, 8 November, 2 October, 11 November, 12 December 1905, 7 February and 10 April 1906, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[35] Letter from Clarke to Department, 6 June 1906, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[36] Departmental report 7 July 1906 and notes on alterations to school building, July 1906. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912. The later building of 1910 is described in LJ Blake, Vision and Realisation, Education Department of Victoria, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1973, vol. 3, p. 1250.

[37] Information given by Mrs Annie Hee to the author.

[38] Letters from Clarke to the Department, 2 February and 1 April 1898. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912. See too AW Elms, ‘A fiery summer,’ and TJ Coverdale, ‘Recollections and personal experiences of the great fires of February 1898’, in White, The land of the lyrebird, pp. 302-10; 296-301.

[39] Letter from Clarke to Department, 27 July 1891. It should be noted that July is a very cold month in South Gippsland. Nevertheless the Department refused, noting, on 28 August 1891, that ‘the summer is coming’. PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[40] The death of a child is reported in a letter from Clarke to the Department, 9 December 1891, and snakes under the school in a letter from Clarke to the Department, 2 December 1889. For Departmental reply, minute of 4 December 1889, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1697, Loch State School 2912.

[41] White, The land of the lyrebird, pp. 28, 37.

[42] ibid.

[43] Loch & District 2001 … From then until now, Loch & District Historical Group, May 2001, p. iii.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples