Last updated:

‘“Tired little Australian Children are still plodding unnecessary miles in wet or shine”: School and Scandal in Mallacoota’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Sarah Mirams.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Free, compulsory secular education was introduced into Victoria under the Education Act 1872 (Vic). In newly established remote rural communities parents would come together, provide lists of potential students and lobby the Education Department for the establishment of their own State School. This article examines the early history of one of Victoria’s most remote schools in far East Gippsland — Mallacoota School, No. 3515, and considers how a school could be an arena where both community unity and divisions could be played out. Poet and journalist EJ Brady made his home at Mallacoota in 1914. An inveterate critic of government bureaucracy and an advocate for the development of East Gippsland, his correspondence with the Education Department provides an insight into political and social dimensions of life in a small community at the beginning of the century.

Mallacoota’s first teacher arrived in far East Gippsland on 1 May 1906.[1] Laurence Kennedy left Cobram East State School, in the prosperous wheat and farming district on the Murray, in April. There he would have enjoyed all the amenities of an established country town — a railway, churches, doctors, shops, a newspaper and even a cordial factory. His new posting was to be very different. Kennedy found himself, after a difficult week-long journey, in Victoria’s most easterly coastal hamlet, 542 kilometres from Melbourne. This article tells the story of Mallacoota State School’s history from its beginnings until the eve of the Second World War.

Academic research into the history of education in Australia is often concerned with exploring the role played by schools, education departments and education bureaucrats in the business of nation building.[2] Histories of small rural schools tend to be celebratory, tracing the stories of principals, teachers and students, and describing how the school experience has changed over time. This study takes a different approach. I am interested in the role the Mallacoota State School played in the community, not as a place of education, but as a part of a community’s social and political landscape.[3]

At first glance the files for Mallacoota State School no. 3515 do not convey the tale of community unity that characterises many small school histories. Letters to the Education Department report scandals involving adultery, kidnapping, poisonings, drunken dances and striking parents. Such correspondence tells us much about the divisions within the community between families, and the struggles for power and influence in a small, isolated settlement. The school, being the only public building shared and in a sense ‘owned’ by the community, became at times one of the arenas where such rivalries could be played out. This article will argue that despite such tensions the school at Mallacoota came to represent to its people the hamlet’s economic viability and future. Families were able at crucial times to put aside their rivalries and personal enmity and work to ensure the school’s survival.

The Most Inaccessible Watering Place in Victoria

The two lakes at Mallacoota were the territory of the Maap people, part of the Kudingal or people who lived by fishing along the south-east coast of the continent.[4] Archaeological surveys reveal that family groups lived and camped around the Inlet for thousands of years.[5] The word ‘Mallacoota’ derives from the Aboriginal place name Malloketer, recorded by Chief Protector Robinson in 1844.[6] Europeans moved into the area to take up cattle runs during the 1840s, encountering fierce opposition. The Mallacoota run was abandoned in 1847, but resumed in 1850. Licences changed hands frequently. Closer settlement came to East Gippsland relatively late in Victoria’s white history with the 1884 Land Act.

When Laurence Kennedy arrived in 1906 he found a small farming and fishing community hugging the river and lake, ringed by dense forest and hills. The Wallagaraugh River flowed through forest from the small town of Genoa to feed the two lakes which opened out onto the sea. Mallacoota’s scenic beauty and isolation earned it a reputation as a place of retreat where the wealthier and more adventurous ‘tired brain worker’ from the city could immerse himself in nature.[7] Dorron’s Lakeside Hotel, a small boarding house and pub, offered some accommodation. Unoccupied land surrounding the lakes was temporarily reserved as a National Park in 1909.[8]

The families living around the lake craved some of the conveniences the tourists were escaping. Here the post office operated from a farmhouse. There were no shops and there was no township. Only bush tracks snaked through the forest and the locals had to rely on small cutters negotiating a shallow sandbar to deliver basic supplies from Eden.[9] During winter the settlement was often cut off for weeks by storms and flooded rivers. The nearest doctor was in Orbost or Eden, both more than a day’s journey away. In summer the hamlet was threatened by bushfires. Surrounded by virgin forest, hemmed in by water, the locals were characterised as pioneers battling against nature to make a living.[10]

Edwin James Brady, bohemian poet and Bulletin writer, is Mallacoota’s best known escapee from the city. Brady first came to Mallacoota in 1909 with the dream of setting up a writers’ camp. He returned in 1914 and took up a selection. He owned a guesthouse and during the 1930s depression helped set up a community farm based on socialist principles.[11] His six children all attended Mallacoota State School. His correspondence regarding the school, both personal and official, provides a vivid insight into community unity and tensions. As a founding member of the Australian Labor Party, Brady had been involved in the radical politics and journalism of 1890s Sydney and was an experienced and at times aggressive lobbyist. Brady developed many schemes for East Gippsland’s development and came to regard Mallacoota as ‘a domain … peculiarly my own’.[12]

State School No. 3515

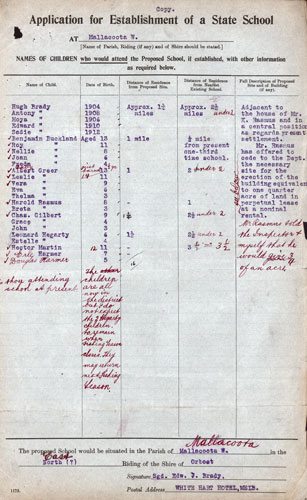

Frank Buckland, a local farmer, filled out the standard Application For Establishment Of a State School form in 1905.[13] Between the Olsen, Coleman, Rankin, Buckland, Reid and Allan families there were twenty-eight children in Mallacoota aged from two to sixteen years. This, Buckland suggested to the Education Department, justified the employment of a full-time teacher.[14] While the more prosperous families could afford to employ a governess, the children of labourers and fishing families may have reached the age of fourteen without any formal education.[15] Their only other option was to row the twenty-four kilometres up river to the nearest school at Genoa. The opening up of land for selection in East Gippsland after the 1884 Lands Act was passed saw the demand for schools grow as selectors moved into the forests. Between 1890 and 1920, forty-nine new schools opened in East Gippsland.[16] This was also a period when, under the Directorship of Frank Tate, Victorian schools were undergoing a period of reform as a result of the Fink Royal Commission into Education 1899-1901. Following the economic devastation wrought by the 1890s depression there was a commitment to create a modern progressive education system in Victoria.[17]

PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1329, Mallacoota State School 3515.

The first school was located on the western side of Bottom Lake, in 1906. The building was neither substantial nor provided with an outhouse. Laurence Kennedy described it in a report to the Department as having ‘no locks, defined grounds or outhouses and is situated 50 yards from the backdoor of WM Allan’s residence and 16 yards from the cow yard’.[21] Such basic school accommodation was not unusual. The centenary history of the Victorian Education Department suggested that, such was the desire for education in the bush, parents were prepared to have their children taught ‘in almost any kind of enclosure: – a bark hut … a room in an operative public house and the cellar of a bacon factory’.[22]

PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 1887, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515.

The condition of the building is starkly shown in the 1910 photograph sent to the Department by Brady. The building looks more like a shed (which it originally was) than a schoolhouse.[23] A building report described it as presenting ‘a very ragged appearance’ and noted care had to be taken not to fall through the broken and rotten floor boards.[24] By 1916 the community began agitating for a new schoolhouse, and also the reappointment of a full-time teacher. Buckland’s original estimated student population had been inflated and within a year of his arrival Kennedy left Mallacoota. Clement Baker, who also taught at the Wangrabelle and Genoa State Schools, found himself responsible for a third school.[25] Rural schools with enrolments of between five and twelve students were expensive for the Department and difficult to staff. Part-time schools and itinerant teachers were a way of supplying the needs of children in isolated areas.[26]

Baker spent two and a half days a fortnight in each school and then left lessons for the children to complete under their parents’ supervision. His working fortnight included rowing the twenty-four kilometres to Genoa to teach for two days and then travelling by horse sixteen kilometres along a track through the forest to the Wangrabelle school. His home was a tent in Genoa where he lived with his wife. Henry Lawson, who visited Brady at Mallacoota in 1910, wrote of how ‘the school master goes around in a boat, a launch, to collect his scholars’.[27] He also noted the ‘little school kiddies’ knew his work from their school papers.[28]

The position of such rural schools was always precarious. To ensure a school’s survival parents had to persuade a remote bureaucracy in the city, using whatever political and economic clout they could muster, that they could maintain enrolments. Such campaigns were often led by strong-willed and determined figures in the community. The Honorable James Cameron MLA, the local member, received a letter on behalf of the Mallacoota families from EJ Brady in July 1916. Brady argued that the local families all had children growing up ‘practically without education’.[29] He urged Cameron to obtain a ‘concession’ from the Minister, implying that Mallacoota was worthy of special consideration despite its small population.[30] Brady then wrote to Tate highlighting the lack of water and lavatories at the school.[31] A petition from the parents at Mallacoota was sent three months later requesting a full-time teacher. The Department seemed unsympathetic, suggesting that the enrolment numbers were too low to warrant the necessary expenditure.[32] Brady’s next letter to Tate argued, ‘settlers in East Gippsland deserved better consideration’. He signed himself EJ Brady, author. As Director of Education, Tate had wide-ranging powers and could ignore the advice of his officers. In a scribbled note on the margin of Brady’s letter he wrote ‘this is an urgent matter which should be attended to at once’.[33]

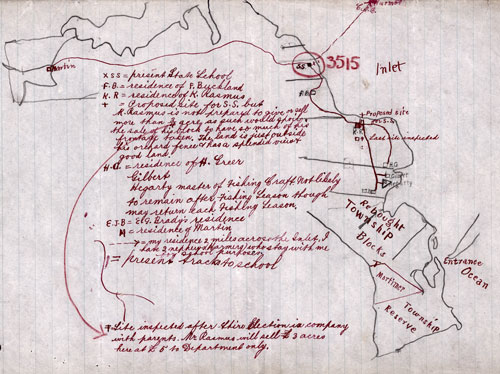

The Department agreed in 1917 to provide a new school building. This was a win for the community, but before long the triumph turned sour as local families competed to provide a site for the new school. Frank Buckland and Carl Rasmus, both from well-established local families, made the first offers to the Department. Brady, a relative newcomer, then put in his bid. Families had an interest in ensuring the proposed school site was close to their own properties and, as such, diagrams were sent in to the Department showing tracks that led from farms to potential school sites.[34] Dr Leach, the School Inspector based in Orbost, had the unenviable task of selecting the site and negotiating with the locals.[35] Brady lobbied hard and sent a stream of correspondence to the Department, which became increasingly angry when his proposal was rejected. In veiled terms he suggested that Leach had been ‘got at’ when the Rasmus block was selected.[36] Brady threatened to use his influence as the author of Australia Unlimited, his recently published survey of Australia, to discredit the Department and let the public know of the proposed ‘internment camp’.[37]

PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

‘There were’, wrote Leach to the Secretary of Education, ‘two irreconcilable factions at Mallacoota’, and ‘much jealousy between the old residents and the more recent arrivals’.[38] Leach may well have been aware that Buckland and Brady were in a long- running dispute over access to two acres of public land used as a recreation reserve and camping ground by seasonal fishermen and locals. This dispute had involved petition and counter petition being sent to the Lands Department.[39] Brady dismissed his opponents as ‘a small group of antediluvian savages who take exception to my humble efforts to spread the Gospel of Progress in this benighted region’.[40]

Both men were public figures in the community: Brady, the journalist and writer, intent on developing Mallacoota and East Gippsland, and Frank Buckland, the local Justice of the Peace. Buckland’s voice is largely muted in the public record. It is Brady’s strident and insistent voice which dominates. Leach’s advice to Tate was ‘peace at any price’ and as ‘neither Buckland nor Brady could build on another man’s property’, the Rasmus site was selected where a temporary building could be erected.[41] However, the matter did not end there. By April, the unused Paynesville schoolhouse, transported by barge, was awaiting the arrival of workers from the Public Works Department to supervise its opening. Brady sent a final barb to the Minister of Education:

But sir, though Nero fiddled Rome continued to burn and while its official Montagues and Capulets in Melbourne are fencing with weapons of departmental sophistry and great satisfaction a number of tired little Australian children are still heavily plodding unnecessary miles in rain and shine … to an old condemned, discreditable and insanitary [sic] building.[42]

The new school opened in late 1918 and Clement Baker was appointed full-time teacher.

Trouble at the Water Tank

The new school building caused further headaches for the Education Department when in 1921 the pupils and their teacher, Miss Violet McMeekin, fell ill. Symptoms included nausea, vomiting, burning sensations in the throat and headaches.[43] The cause of the illness was traced to the water tank that a local man, Robert Bruce, had built and installed at the school. Brady, Buckland and Rasmus put aside their former grievances and met as a group of concerned parents. Water samples were sent to the Public Health Department for analysis. Tests revealed high levels of zinc and lead compounds in the water, and two per cent hydrochloric acid.[44] Letters were sent to the Department demanding action. Mr GA Osborne, the Inspector of Schools, came down and chaired an enquiry. Harold Rasmus, a schoolboy, claimed to have seen Bruce accidentally kick a bottle of spirits of salts into the tank.[45] Bruce refused to attend the meeting and denied the accusations vigorously, claiming that if the Department asked ‘about the character of the boy Rasmus you will find no one in the district daring enough to believe a word he says’.[46] At the conclusion of the enquiry Bruce was directed to replace the tank, and no formal criminal charges were laid.

Such a public drama soured the relationship between Bruce and some families in Mallacoota for several years and the school became the arena where these tensions were played out. Bruce was asked to explain the non-attendance of his children at the school in 1923 and wrote that he had kept his children at home to save them from catching diphtheria. He accused the Brady family of bringing the disease from Melbourne. The matter, he claimed, was hushed up to stop quarantine restrictions being implemented leading to the forcible closure of Mallacoota House, the guesthouse Brady owned.[47] Bruce went on to report that the local schoolroom had been used to hold a ball where large quantities of alcohol were sold and drunk. This party, he alleged, went on until four in the morning, ‘a ramshackle picture machine is used in the school as a blind to cover this disgraceful fracas’.[48] Bruce then accused two drunken locals of kidnapping his two boys and keeping them in a shed at Raheen, the Brady family home, for two days. This was done with the full knowledge, he claimed, of Violet McMeekin.

Both the School Committee and the Head Teacher were asked to account for these accusations, though the Department appeared more interested in the intoxicating liquor than the kidnapping.[49] Violet McMeekin denied the accusations, writing that she frequently showed cinematographic picture shows in the school for the benefit of the children, but that no alcohol was consumed.

As for dances — well since I was the only girl in Mallacoota for the greater part of the time, it was only on rare occasions that we could have a dance at the picture show. I took a great deal of interest in the school and worked as hard as I could for the few children there. It has hurt me deeply to know that my work has been rewarded by such false reports being sent in. What encouragement does it give to a teacher — especially a lady teacher — to work for the school?[50]

Violet was forced to leave Mallacoota when the senior Bradys departed for Melbourne. It was unacceptable for her to stay at Raheen unchaperoned with Brady’s two teenage sons. She could find no other affordable accommodation.

In the poisoning scandal we see a realignment within the community. Brady, Rasmus and Buckland presented a united front to the Department as the responsible voice of Mallacoota. They put aside their personal animosity and worked for the good of the school and the students. The school now became a battleground between the Brady and Bruce families. Violet was a friend of the Brady family and was particularly close to Moya Brady, the eldest daughter, and maybe this is why Bruce reported her to the Department. In the local history, the Bruce family joins the Buckland, Rasmus and Allan families as the pioneers of Mallacoota — there is no hint of scandal.[51]

Brady’s personal papers, however, provide some tantalising glimpses of the local gossip. In one letter, a friend of Brady reports on a petition circulating in 1924 accusing Brady of encouraging the Bruce children to run away from home. Tom McDonald wrote that, ‘it was signed by the elite of Mallacoota West namely Lady Ellen Dobie, Hosie Wilkins, Mr and Mrs Dawson, Robert and Freda. All quite the nastiest people as the Bulletin puts it’.[52] Competition in the tourist industry between the local families may have caused further tension. Brady attempted to have the Inlet declared a dry zone during the 1920s, which if successful, would have effectively put the Dorron’s Lakeside Hotel out of business.[53] This would not have endeared him to some families.

Scandal on the School Committee

Such a remote school was always hard to staff and for more than five months after Violet McMeekin’s departure there was no school teacher at Mallacoota. Mrs Dawson wrote to the Department complaining that if there was no teacher appointed ‘the residents will have to move away to get their children taught’.[54] Victoria followed the New Zealand experience, where married men with families were less likely settle in rural areas where there was no operating school.[55] Teachers also fulfilled an important social role in rural communities in organising sporting and cultural events. Carl Redenbach, who eventually replaced Violet McMeekin, was one such teacher. When the locals learned that the Department intended to transfer Carl Redenbach in 1925, the parents sent in a petition, requesting he be kept on, as ‘in a remote place like Mallacoota a young male teacher of Mr Redenbach’s energy and ability is valuable human asset’.[56] In this, as in other community action, we see previously warring factions, the Brady, Rasmus, Dobie, Buckland and Bruce families, coming together in support of the school.

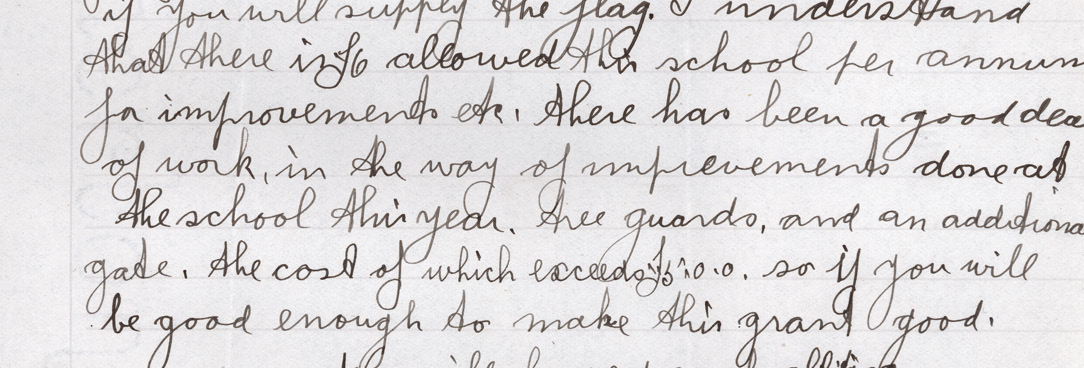

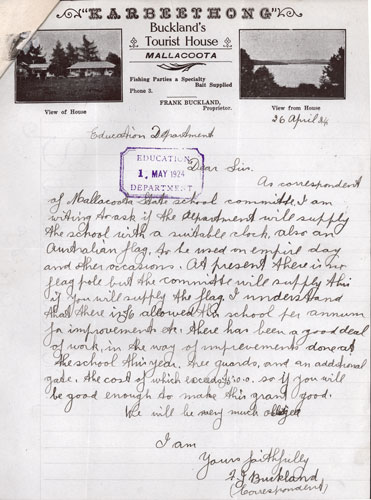

The school committee was the officially recognised body that liaised between the Department and the school. Members were elected from the parent body. Tate introduced this system into Victoria in 1910, after seeing it operating successfully in New Zealand. He hoped it would encourage local communities to become more involved with their children’s education.[57] The committee managed a small maintenance budget, raised money for the school, obtained accommodation for teachers in rural areas, investigated complaints against teachers, and reported to the Department on the condition and management of the school. Much school committee correspondence dealt with the more mundane aspects of school life. Frank Buckland, the Mallacoota school committee correspondent, requested a school clock, Australian flag, tree guards and a gate from the Department — all requests were denied.[58] The Department approved the Head Teacher closing down the school during the February 1926 bushfires.[59] The school committee agreed to fence the school paddock after Mr Bristow threatened to withdraw his children from the school unless his children’s pony could be housed.[60]

PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

When the entire Mallacoota school committee, including Frank Buckland and Norma Brady, resigned from their positions in 1931 the Department was yet again required to investigate the goings-on at Mallacoota. The committee members objected to James Latta and Mrs Ellen Bruce serving on the committee.[61] According to correspondence, Latta was living openly with Mrs Bruce in the Bruce family home. Robert Bruce was concerned his children knew of this relationship and in Frank Buckland’s view Mr Latta was ‘an improper person to act on a public body, least of all a school committee’.[62] The Inspector sent down to investigate the claims reported to the Department: ‘I gather that nobody in this place wants to antagonise Latta. He is said to be a man of considerable force of character and rather good address determined to serve his own ends and not too scrupulous about the means to do it.’[63] An Order of Council, signed by the Minister for Public Instruction on behalf of The Governor in Council on 26 January 1932, officially removed both Latta and Ellen Bruce from the school committee.[64] James Latta appears to have been an unpopular resident, and the parents’ attempt to have him dismissed from the school committee may well have been a public and official denunciation of both his relationship with Ellen Bruce and his influence within the community.

Depression

The depression of the 1930s saw teachers and schools in Victoria under attack from politicians and the press.[65] There was enormous pressure on the Labor government to cut costs and the State Finance Committee recommended the closing of rural schools with small attendances, increasing fees, and restricting access to secondary education.[66] In such a precarious economic climate the people of Mallacoota came together and launched a campaign to have the schoolhouse removed from its site on the Rasmus property to the township reserve surveyed in 1919.[67] The ‘township’ had been only lines on the parish plan until the 1920s when a road linked Mallacoota to the newly opened Princess Highway and the outside world in 1921. Tourism became a significant seasonal industry during the 1920s with the Brady, Allan, Dorron and Buckland families providing accommodation, tours and transportation for the tourists who came to visit ‘the gem of Victoria’.[68] The locals wanted the school in town, where, they claimed, it was closer to most families, but one also suspects, as a way of signalling Mallacoota’s status as a permanent and viable rural community, rather than a remote farming outpost.

Initially the Education Department rejected the proposal. The small enrolment (in June 1934 there were only thirteen students) could not justify such expenditure.[69] Undeterred, a letter was sent to the Secretary in January 1935 stating that at a meeting the parents had voted to withdraw their children from the school until their demands were met, but had ‘wisely decided’ to wait until the Department visited. The school committee also noted that six snakes had been killed in the school grounds that summer.[70] Parents elicited the support of a number of politicians, most of whom had a connection with the Brady family through friendship and politics. Those who wrote letters in support of the school included AE Lind, their local Member of Parliament, James Cameron, a former MLA, and Edward Tunncliffe, Acting Premier of Victoria.[71] The parents demonstrated local support for the scheme the following May by sending the Department the names of those locals who supported the school’s relocation. The names included former students as well as locals who also offered their labour to assist in clearing and fencing the new site.[72]

The names on this petition include most of the families involved in the various scandals and campaigns over the previous thirty years. These included the Brady, Buckland, Allan, Latta, Bruce, Bristow, Greer and Bolton families, testament to the importance the school had in the community even for those who no longer had children attending. The campaign was successful and in October 1935 the Public Works Department agreed to relocate the school into the township.[73] There is no reason given for the Education Department’s change of heart, but presumably the work of the politicians and the people of Mallacoota contributed to a successful outcome. It should be noted, though, that both the Labor and the subsequent conservative government were conscious of the strong influence of rural electorates in the state parliament during this period.[74]

Conclusion

A sociological study into country life carried out during the Second World War by the Melbourne University Faculty of Agriculture, found that country people believed that self-help and cooperation were dominant features of rural life. The researchers also found, however, that country towns could be divided along religious, economic or personal lines. Such divisions, and the subsequent tensions that developed, were more intense in the smaller towns where ‘people’s relatively few contacts and interests contain all the emotion which in a larger community could be more widely dispersed’.[75] The Education Department records certainly create the impression of Mallacoota being an isolated rural hamlet beset with jealousy, gossip and competition. The school at times became the site where personal grievances were played out between neighbours.

The Melbourne University researchers also suggested that in such deeply divided communities, cooperative and community effort became ‘almost impossible’.[76] At Mallacoota, though, this does not appear to have been the case. The school, as well as representing parents’ hopes for their children’s future, became a vital element in Mallacoota’s transformation into a permanent, viable settlement. Its importance is measured by the fact that locals could put aside their personal prejudices, albeit often temporarily, and work to ensure the school’s future. The school also played an important role in developing the political and social dimension of community life, and Brady appears to have played a significant role here. While sometimes a difficult neighbour, he was willing to harness his political contacts and use his skill as an author to, as a local farmer’s wife wrote, ‘do a little pen-fighting for our little district’.[77]

Endnotes

[1] Laurence Kennedy to the Secretary of Education, 3 May 1906, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1329, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515. Note that School 3515 was known as both Mallacoota Inlet State School and Mallacoota State School in the department files.

[2] AG Austin, Australian education, 1788-1900: church, state and public education in colonial Australia, Pitman, Melbourne, 1980; Bob Bessant, Schooling in the colony and state of Victoria, Centre for Comparative and International Studies in Education, School of Education, La Trobe University, Melbourne, 1983; G Rodwell, ‘Domestic science, race, motherhood and eugenics in Australian State Schools, 1900-1960’, History of Education Review, vol. 29, no. 2, 2000; M Crotty, Making of the Australian male: middle class masculinity 1870-1920, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2001.

[3] This approach is more commonly taken in histories of independent schools. See for example W Bate, Light school down under: the history of the Geelong Grammar School, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990; Kathleen Fitzpatrick, PLC, Melbourne: the first century, 1875-1975, Presbyterian Ladies College, Melbourne, 1975.

[4] S Wesson, An historical atlas of the Aborigines of eastern Victoria and far south-eastern New South Wales, Monash Publications in Geography and Environmental Science, no. 53, Monash University, 2000.

[5] K Thomson, A history of the Aboriginal people of East Gippsland, Report Prepared for the Land Conservation Council Victoria, Melbourne, 1995.

[6] Wesson, An historical atlas, p. 126.

[7] S Mirams, ‘For their moral health: James Barrett, urban progressive ideas and National Parks in Victoria’, Australian Historical Studies, no. 120, October, 2002; S Mirams, Mallacoota Lakes National Park: the forgotten park, MA Thesis, Monash University, 1999.

[8] Advertising brochure for Mallacoota House, NLA, Brady Papers Ms 206, series 13, box 54, folder 13.

[9] For the story of these boats see J Little, Down to the sea, McMillan, Sydney, 2004.

[10] See for example EJ Brady, ‘East Gippsland: a neglected country’, Herald, 23 June 1910.

[11] JB Webb, A critical biography of Edwin James Brady 1869-1952, PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1972.

[12] EJ Brady to TG Ellery 20 July 1920, NLA, Brady Collection Ms 206, series 13, box 52, folio 5.

[13] Application for the Establishment of a State School 1905, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1329, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[14] ibid.

[15] Chris Harrison to Secretary of Education 20 December 1902, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1329, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[16] LJ Blake (ed.), Vision and realisation: a centennial history of state education in Victoria, vol. 3, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1973, p. 1055.

[17] ibid., vol. 1, pp. 323-27.

[18] Application For The Establishment Of State School 1905, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1329, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[19] Chris Harrison to Secretary of Education 20 December 1902, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1329, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[20] ibid.

[21] Laurence Kennedy to Secretary of Education 31 October 1906, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[22] Blake, Vision and realisation, vol. 3, p. 1057.

[23] Photograph of Mallacoota State School c.1910 , PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515.

[24] Building Report 6 December 1910, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515.

[25] Clement Baker to the Secretary of Education 31 October 1906, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515.

[26] Blake, Vision and realisation, vol. 3, p. 398.

[27] Henry Lawson to Jim Lawson 22 March 1910, in C Roderick (ed.), Henry Lawson: letters 1890-1922, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1920, p. 293.

[28] ibid.

[29] EJ Brady to Hon James Cameron MLA 17 July 1917, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota Inlet State School 3515.

[30] ibid.

[31] EJ Brady to Frank Tate, 30 July 1916, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[32] Petition for a Full Time Teacher, Mallacoota Inlet State School, 5 September 1916, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[33] EJ Brady to Frank Tate, 30 July 1916, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[34] EJ Brady to Secretary of Education, 24 September 1917, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[35] Dr Leach is perhaps best known as the teacher who introduced nature studies to the Victorian primary school curriculum. See C Dowe, ‘Nature’s life long friends: thryptomene, nature study and the declaration of the Lakes National Park’, Gippsland Heritage Journal, no. 29.

[36] EJ Brady to Frank Tate, 17 October 1918, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[37] EJ Brady to Frank Tate, 27 October 1918, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 1887, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[38] Dr JA Leach, Memo to Director of Education, 10 November 1917, PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[39] Department of Land and Survey to EJ Brady 19 May 1917, NLA, EJ Brady Papers, Ms 206, series 13, scrapbook; EJ Brady to Minister of Public Works, 27 April 1917, NLA, EJ Brady Papers, Ms 206, series 13, box 54.

[40] EJ Brady to The Minister for Public Works, 27

April 1917, NLA, EJ Brady Papers, Ms 206, series 13, box 5.

[41] Dr JA Leach, Memo to Director of Education, 10 November 1917, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[42] EJ Brady to Minister of Education, 30 April 1919, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[43] EJ Brady to Director of Education, 29 October 1920, PROV, VPRS 796/P0, Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[44] GA Osborne, Inspector of Schools to The Director, Education Department, 21 February 1921, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[45] ibid.

[46] Robert E Bruce to the Education Department, 19 March 1921, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[47] Robert E Bruce to Secretary of Education, 28 August 1923, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1660, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[48] ibid.

[49] Memorandum to the School Committee No. 3515, 13 September 1923, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[50] Violet McMeekin to Secretary of Education, 4 October 1923, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1660, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[51] K Howe, Mallacoota reflections, Mallacoota and District Historical Society, Bairnsdale, 1991.

[52] T McDonald to EJ Brady, 10 April 1924, NLA, EJ Brady Papers, Ms 206, series 13, box 52, folder 7.

[53] Petition to Licences Reduction Board from EJ Brady, December 1925, NLA, EJ Brady Papers, Ms 206, series 13, box 52, folder 5.

[54] Mrs Dawson to Secretary of Education, 2 February 1924, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota Primary School 3515.

[55] M Lake, The limits of hope: soldier selection in Victoria 1915-1938, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987, p. 163; G McGeorge, ‘The long haul to full school attendance’, New Zealand Journal of History, vol. 40, no. 1, April 2006, p. 27.

[56] Petition to Secretary of Education, 12 March 1925, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[57] Blake, Vision and realisation, vol. 1, p. 127.

[58] Frank Buckland to the Secretary, 26 April 1924, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[59] Secretary to the Head Teacher, 24 February 1926, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota Primary School 3515.

[60] Mallacoota State School Committee to Secretary, 4 August 1930, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota Primary School 3515.

[61] Frank Buckland to Secretary of Education, 13 December 1931, PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1737, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[62] Confidential Report, 21 January 1932, PROV, VPRS 796/P0, Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota Primary School 3515.

[63] ibid.

[64] Order of Council, 26 January 1931, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota Primary School 3515.

[65] Bessant, Schooling in the colony, p. 98.

[66] ibid., p. 99.

[67] A Brady, ‘Edward Lees, Surveyor of Mallacoota’, Gippsland Heritage Journal, no. 12, June 1992.

[68] Petition to T Hogan, Premier, 30 January 1930, Department of Crown Land and Survey, National Park Files, Mallacoota Inlet National Park, Rs.1176.

[69] Secretary of Education to James Cameron MLA, 5 June 1935, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[70] WP Bolton to the Education Department, 28 January 1935, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[71] The Hon AE Lind to Secretary, 14 February 1935 and 22 May 1935; HR Cameron to Secretary, 5 June 1935; Edward Tunncliffe to Secretary, 27 August 1935 and 14 October 1935, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 796, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[72] ibid.

[73] Public Works Department to Secretary of Education, 16 October 1935, PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books: Primary Schools, Unit 746, Mallacoota State School 3515.

[74] Bessant, Schooling in the colony, p. 101.

[75] AJ & JJ McIntyre, Country towns in Victoria: a social survey, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1944, p. 262.

[76] ibid.

[77] Mrs Stevens, Wangrabelle, to EJ Brady, 25 July 1925, NLA, EJ Brady Collection, Ms 206, series 13, box 52, folder 8.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples