Last updated:

‘Landing A Vote: The past importance of land ownership as an electoral qualification in Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Sonia Jennings.

When Victoria celebrated 150 years of responsible government in 2006, Public Record Office Victoria marked the event with an exhibition. Jill Barnard and Sonia Jennings were commissioned to research and write a catalogue to complement the exhibition and this article draws on research conducted for that purpose. Our short history used the Land Acts to illustrate the role of government and legislation in the lives of ordinary Victorians. Land ownership and electoral rights were inextricably related and it is interesting to trace the steps taken by successive governments to extend and refine the electoral franchise.

When researching for a project on the subject of responsible government,[1] it occurred to me how much we take for granted our right to vote — the concept of ‘one man, one vote’ seems such a basic civil right that it is hard to fathom a time when this wasn’t so. But what really struck me too was the importance of land ownership in the past and its place in the evolution of our democratic rights. It is still the great Australian dream to own a house with a bit of dirt around it, but how would we feel today if it was an essential requisite for citizenship? Perhaps, like me, most people today would also be surprised to find that there were property conditions attached to electoral representation until 1950.

To look at the way in which our electoral system evolved we need to go back about 150 years, to 1851 to be exact, when Victoria achieved formal separation from New South Wales. The new colony was first governed by a Legislative Council and at this time ten of the Council’s thirty members were nominated by the Lieutenant Governor, Charles La Trobe, and the rest were elected. Gender (no surprise there) and property qualifications imposed restrictions on who could stand as a candidate and who could vote for the Legislative Councillors. Soon, however, a select committee was appointed to draw up a constitution for the new colony. While this was happening Victoria was in the midst of the gold rush and it is fairly safe to say that the majority of the population was more concerned with striking it rich than worrying about constitutional matters.

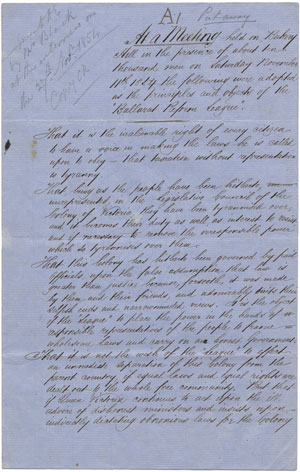

However, conditions for miners on the Victorian goldfields were far from satisfactory. Services were abysmal in mining areas, yet mining licence fees could be as high as 30 shillings a month. This should be compared with the situation of squatters who could hold around 20 square miles of land for an annual tax of 10 pounds.[2] The goldfields were administered by government-appointed commissioners who were charged with maintaining order and collecting licence fees. This was often carried out in a brutal and arbitrary manner. Many miners had brought with them the egalitarian ideas of the British Chartist movement, so it is not surprising that they agitated for better treatment. The Ballarat Reform League, organised under the leadership of Peter Lalor, was one such group which was not happy with their lot. The League believed that taxation without representation was tyranny and their aim was for universal manhood suffrage with elections by secret ballot. They also opposed property qualifications for members of parliament and believed that such members should be paid. These ideas were a bit before their time, although fortunately not totally beyond consideration.

PROV, VPRS 4066/P0 Inward Correspondence, Unit 1, Item no. 69.

As we know, things came to a head between miners and administrators at the Ballarat diggings in December 1854, resulting in the famous Eureka rebellion. In the aftermath of this tragedy a Royal Commission examined conditions on the goldfields and several changes were made.[3] The most significant change in terms of democracy was the abolition of the miners’ licence fee and the introduction of a Miner’s Right (renewable annually for 1 pound) which was recognised as a qualification for voting. In addition, twelve new seats were added to the Legislative Council, eight of these being for representatives of the goldfields.

On the face of it this seems to have been an amazing victory for miners, to have achieved the right to vote without owning any land, but in reality miners needed to have been in possession of a licence ‘for the space of twelve months or upwards’ and to have occupied or mined in a particular area for a least six months prior to electoral registration.[4] It should also be remembered that registration was not just a matter of going to your local Post Office. Consequently, the limitations placed on the miners’ electoral qualification, along with the practice of plural voting for those who owned land in several electorates, effectively diminished the power of the miners and small landowners.

With miners being a somewhat fluctuating, moving population, the organisation of elections in the goldfields areas in the 1850s were not without their problems. An 1855 petition to the Governor from electors resident at ‘Mag-pie’ gives a good example. The petitioners requested that a polling booth be established at ‘Mag-pie’ rather than at Creswick. They pointed out that a ‘Rush had taken place of from 8,000 to 10,000 people to the Mag-pie’ and that Creswick was practically deserted.[5] Similarly, the Warden of Blackwood wrote on behalf of ‘four to five hundred landholders’ in North Bourke, stating their concern that no polling booth would be available in their vicinity.[6]

When the Victorian Constitution was enacted in 1856 it brought with it the ground-breaking idea of the secret ballot. The introduction of the secret ballot had been preceded by a long period of debate. Opponents believed open voting was honest and manly, while the secret ballot was underhand or devious. At a time when a smaller franchise applied, that is, when voters were propertied men, many believed that such voters should be accountable; that they should be seen to be voting in the public interest, rather than for personal or private gain.[7]

At this stage it should be pointed out that, before the secret ballot, elections had more in common with Brownlow medal nights than polling days as we know them now. Before 1856, elections were often rowdy, drunken affairs. The absence of suitable public buildings in many communities at the time meant polling booths were usually set up in hotels. This was a boon to publicans as the open nature of elections meant candidates would often ‘treat’ electors to meals and drinks in order to win their votes. James Henty articulated his concern with this arrangement in August 1855 when he declined a request to serve as a returning officer. Henty stated that he ‘had the greatest abhorrence to be shut up in a small room of an ordinary public house amidst the scenes which usually take place at elections when held in houses of that description’.[8] It was not until 1865 that an Act was passed nominating schools as appropriate polling places and declaring that ‘no polling booth shall be in any house licensed for the sale of fermented or spirituous liquors or upon the premises appertaining to such house’.[9]

Under the open system, votes were recorded in a book or on cards dropped into a box, with a progressive count being taken during the poll. This system was open to many forms of coercion and corruption on the part of both candidates and electors. For example, an employer or landlord could pressure his workers or tenants to vote for candidates who supported his own interests. After the election, candidates could peruse the records to see who voted for whom and in some instances voting records were published in the newspapers of the day. In reporting on the election in Melbourne in 1853, the Argus stated:

Many of these publicans were eager canvassers and most of them could influence a few votes. In addition to these, we find very many names of those interested in public-house property, although not the actual holders of licenses; we find nearly all the wine-merchants and brewers in town, and their connections, scrambling to render their homage to the pet of the publicans.[10]

The 1856 Victorian Constitution allowed a greater proportion of men to vote, but it was not the universal manhood suffrage which the Ballarat Reform League had agitated for in 1854. Electors of the Legislative Assembly (lower house) needed to have freehold property valued at 50 pounds or a leasehold of 10 pounds, while candidates were required to own freehold property to the value of 2,000 pounds or a leasehold of 200 pounds per annum. Excluded from the franchise were young men living in their parents’ homes, all lodgers and live-in employees.

The attitude of the time was exemplified in a statement made by those drafting the constitution in 1853:

A high freehold qualification should be required, partly to ensure that its members should hold a large stake in the land, but more especially that it may consist of men who may reasonably be expected to possess education, intelligence, and leisure to devote to public affairs.[11]

Even experienced former British parliamentarian and barrister, Charles Gavan Duffy, was subject to these conditions when he was persuaded to stand for election in Victoria. Fortunately for Duffy, an Irish reformist who arrived in Australia in 1855, he had a good deal of public support. An amount of 5,000 pounds was raised through public subscription for Duffy to acquire a property and stand for parliament. Duffy duly purchased a house in Hawthorn and was elected to the Legislative Assembly. He did not, however, represent Hawthorn. His electorate, known as Villiers and Heytesbury, was in the vicinity of Port Fairy and Warrnambool. Nevertheless, to Duffy’s credit, he began his political career by sponsoring a bill to abolish the property qualification for members of the lower house.[12]

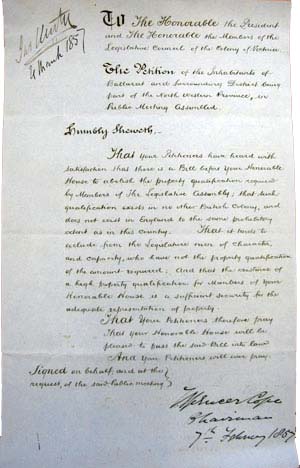

In 1857 petitions from mining districts soon began arriving on the desks of the various upper house members, ‘praying’ for removal of the property qualification. Two such petitions now held at PROV pointed out that the property qualification ‘exists in no other British Colony, and does not exist in England to the same prohibitory extent as in this country’ and that ‘it tends to exclude from the Legislature men of character and capacity’. The petitioners were exceedingly conservative in their wishes as they had no desire to alter the property qualification for members of the upper house, seeing that ‘as sufficient security for the adequate representation of property’.[13]

PROV, VPRS 2599/P0 Original Papers Tabled in the Legislative Council, Unit 535.

The petitioners would no doubt have been pleased with their efforts when the bill was passed in November 1857 and universal manhood suffrage was introduced for voters in Legislative Assembly elections. Property qualifications continued, however, for those voting in Legislative Council elections or standing as candidates for the Council. In fact an Act introduced in 1863 allowed proportional plural voting for property owners, which, in the eyes of some, equated to a disenfranchisement of the lower classes.[14] While later legislation sought to abolish plural voting, there is evidence to show that in 1874 it was still seen as acceptable. Minutes of the Constitution Act Amendment Committee record that the property qualification to attain the right to three votes was to be increased from 150 to 250 pounds per annum.[15] Plural voting was not abolished until 1899 for the lower house and continued until 1938 in the upper house.[16]

When the Constitution was drafted in 1853 no consideration was given to enfranchising women. Women’s place was seen to be in the private sphere and not the public one. However, in 1863 the government decided that the municipal rolls would be used as a basis for compiling the state electoral rolls. The Act which validated this procedure used the phrase ‘all persons’ when referring to those on the municipal rolls. What the legislators overlooked, in this instance, was the fact that many women owned property and were registered to vote in municipal elections. Some of those women had the audacity to vote in 1864 Legislative Assembly elections. The Argus, reporting on the election in 1864 noted:

At one of the polling booths in the Castlemaine district a novel sight was witnessed. A coach filled with ladies drove up, and the fair occupants alighted and recorded their votes to a man, for a bachelor candidate – Mr Zeal… at the Sandhurst election also the fair sex to the number of ten or a dozen exercised the franchise and recorded their votes for their favourite candidates.[17]

Women, however, would need to wait another forty-four years to have their votes recognised: the Municipal Act was hastily amended in early 1865 on the grounds that women had not obtained the vote through deliberate intention.[18] It was not until the 1880s that women began to organise and actively campaign for the right to vote in Victoria.

PROV, VPRS 12800/P1 Photographic Collection: Railway Negatives: Alpha-numeric Systems, H 4910.

It should also be noted that the Married Women’s Property Act was put in place in 1884. Prior to this time married women were not able to own land in their own names. In addition, single women selecting land or taking it up under the conditions of Closer Settlement were required to declare ‘I am not a married woman’ or ‘I am a married woman but have obtained a decree of judicial separation’.[19]

In time a progression of constitutional changes occurred to make Victoria’s government not only responsible, but also representative. However, it is interesting to reflect on the fact that, despite the ground-breaking changes which emerged out of the Eureka uprising and Victoria’s ‘first in the world’ status in respect of the secret ballot, by 1900 Victoria was the only parliament which maintained a property qualification for candidates in the upper house.[20] The qualification endured until 1950 and Victorians could then claim to have universal suffrage – except for Indigenous people, but that’s another story.

Endnotes

[1] Sonia Jennings and Jill Barnard, of Living Histories, researched and wrote a catalogue in 2005 to accompany the PROV Exhibition ‘People and Parliament, Landmark Decisions, 1855-2006’.

[2] M Kiddle, Men of yesterday, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1961, p 165.

[3] G Serle, The golden age: a history of the colony of Victoria 1851-1861, Melbourne University Press, 1968.

[4] Qualification of Electors 1855, PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, Unit 208; R Wright, A people’s council: a history of the parliament of Victoria, 1856-1990, Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 38-9.

[5] Petition to Governor Hotham from electors resident at ‘Mag-pie’, PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence 1, Unit 207, 1855.

[6] Letter to Colonial Secretary, 4 September 1855, PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, Unit 207.

[7] M McKenna, ‘Building a closet of prayer in the new world: the story of the Australian ballot’ in M Sawer (ed.), Elections: full, free and fair, Federation Press, Sydney, 2001, p 48.

[8] Letter from J Henty, 8 August 1855, PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, Unit 208.

[9] Electoral Act 1865.

[10] Argus, 28 May 1853.

[11] Recommendation of the Select Committee of 1853 quoted in G Serle, ‘The Victorian Legislative Council 1856-1950’, Historical Studies Selected Articles, first series, Melbourne University Press, 1964, p. 128.

[12] JE Parnaby, ‘Duffy, Sir Charles Gavan (1816-1903)’, Australian dictionary of biography online, www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A040109b.htm (accessed June 2005).

[13] Petition to Legislative Council from the inhabitants of Ballarat and surrounding district, 7 February 1857, PROV, VPRS 2599/P0 Original Papers tabled in the Legislative Council, Unit 535.

[14] B Barrett, The civic frontier, Melbourne University Press, 1979, p 295. Property with a net annual value (NAV) of less than 100 pounds entitled the ratepayer to one vote; a NAV of 100-150 pounds allowed two votes; and property with a NAV greater than 150 pounds allowed three votes.

[15] PROV, VPRS 7630/P1 Minute Books of the Constitution Act Amendment Committee, Unit 1, 1874.

[16] Parliament of Victoria, www.parliament.vic.gov.au/vote.html (accessed June 2005).

[17] Argus, 5 November 1864, p 4.

[18] A Summers, Damned whores and God’s police, Penguin, Melbourne, p. 394; Wright, A People’s Council, p. 39.

[19] For example, see Land File for Alice O’Hara, PROV, VPRS 660/P0 Licensing Court Registers, Unit 418A.

[20] Parliament of Victoria, www.parliament.vic.gov.au/council/info_sheets/ Legislative_Council_History.htm (accessed June 2005).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples