Last updated:

‘Her Majesty’s Collingwood Stockade: A Snapshot of Gold Rush Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Peter Andrew Barrett.

The word ‘stockade’ has been associated, particularly in recent years, with the Eureka Stockade conflict at Ballarat, which has overshadowed the word’s other use in gold rush era Victoria, as the term for a low security prison. Several of these stockades were opened in metropolitan Melbourne at the height of the gold rush including Pentridge (1850), Richmond (1852), Collingwood (1853) and the ‘Marine Stockade’ at Williamstown (1853). They supplemented other stockades constructed closer to the goldfields, and the prison hulks moored off Williamstown. The stockades contained prisoners with shorter sentences, or those having served part of their sentences on the hulks.

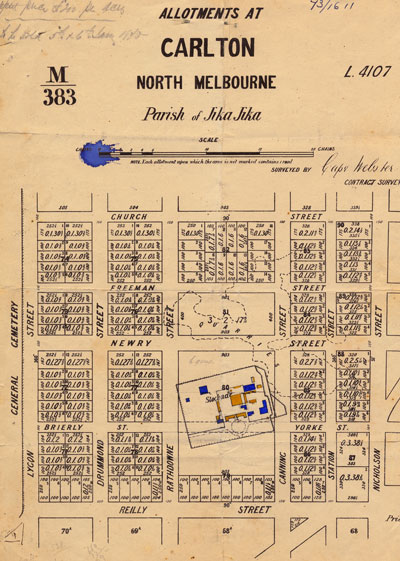

With few residents during the gold rush, North Carlton was colloquially referred to as Collingwood, in reference to the small settlement to its east, and its relative isolation from Melbourne made it an ideal location for one of the city’s earliest penal institutions — the Collingwood Stockade. Today, North Carlton’s rows of elegant Victorian terrace housing and wide streets now cover the district’s early history as the site of one of the Colony’s largest prisons.

The stockade’s register of ‘Personal Description of Prisoners Received Collingwood Stockade 1856’, held at Public Record Office Victoria, provides a fascinating documentary account of its prisoners, which totalled more than 300 at one stage. But also of interest in the register is a description of each prisoner’s origin, with many having only recently arrived in the Colony, from all corners of the globe. The Collingwood Stockade’s inmates reflect the cultural diversity of gold rush era Victoria. Most were single young men, some as young as fifteen. With no family in Victoria, and probably a limited social network, it is of little surprise that many soon found themselves in trouble with the law.

After the Collingwood Stockade closed in 1866, its buildings, many built by its inmates, were converted into an asylum for the reception of ‘lunatics’ transferred from Melbourne gaols. This institution, the Collingwood Stockade Asylum, existed until 1873, when the site was converted to its current use as Lee Street Primary School. Stockade prisoners quarried bluestone on land that now forms Curtain Square in North Carlton, and some of this was used on the stockade’s buildings. After these were demolished, the bluestone was salvaged and used for the footings and flaggings of the 1878 primary school building. This bluestone, and a stone tablet from the former Governor’s House fixed to the wall of the school, are today the only visible physical reminders of the former Collingwood Stockade.

North Carlton’s rows of elegant Victorian terrace housing and wide streets, which define most of the physical character of the suburb, provide a thin veil of Victorian respectability over a less salubrious layer of the district’s early history. With few residents during the gold rush, North Carlton was colloquially referred to as Collingwood, in reference to the small settlement to its east. Its relative isolation from Melbourne made it an ideal location for one of Melbourne’s earliest penal institutions — the Collingwood Stockade. The sounds of children merrily playing at Lee Street Primary School today is in stark contrast to the sounds from this same site one hundred and fifty years ago, when prisoners were mustered for labour on the bluestone quarries of the stockade.

Victoria of the 1850s was prosperous and diverse, but it could also be a dangerous and unlawful place. Within days of separation from New South Wales, gold was discovered in Victoria, and with this came an influx of immigrants from around the world. The population of Victoria increased from 77,000 in 1851 to more than 500,000 a decade later. Of more interest, and quite often forgotten, is the shift that occurred at this time from purely Anglo-Celtic immigration, to a broader array of arrivals including Chinese, French, Germans and Americans, some arriving from the Californian goldfields. Many convicts and ex-convicts from New South Wales, Norfolk Island and Van Diemen’s Land also headed to Victoria in an attempt to find wealth. With an increasing population, crime became more prevalent and maintaining law and order more difficult.

New facilities were needed during the gold rush to relieve the overcrowding of Victoria’s gaols. Stockades, a type of makeshift prison, were built in metropolitan Melbourne at Pentridge (1850), Richmond (1852), Collingwood (1853) and the ‘Marine Stockade’ at Williamstown (1853). They supplemented other stockades constructed closer to the goldfields, and prison hulks moored off Williamstown. Dangerous prisoners were confined to the hulks, which provided better security, and the prisoners with shorter sentences, or having served part of their sentence on the hulks, were accommodated at the stockades.[1]

PROV, VPRS 688/P0 Letter and Memoranda Book, Inspector-General’s Office to the Superintendent, Collingwood Stockade, Unit 1, entries for December 1854.

The word ‘stockade’ has been associated, particularly in recent years, with the Eureka Stockade conflict at Ballarat. Although the main similarity between the two sites is their use of a stockade, that is, a fence of timber stakes to enclose each respective site, the Collingwood Stockade did play a small part in quelling the civil disturbances in the Colony in December 1854. With the growing unrest on the goldfields, the Inspector General of Penal Establishments, John Price, arranged for Collingwood Stockade to be a depot for the assemblage of one hundred warders in readiness to ‘march anywhere at anytime’. But this army of men would see no action on the Ballarat goldfields. Instead, during the Eureka conflict, they were deployed to assemble at the Melbourne Gaol to maintain law and order in the city. This left the stockades and hulks understaffed and resulted in an attempted rush for freedom by prisoners at Pentridge Stockade.[2]

There was a financial motive behind establishing the stockades. In contrast to more conventional types of gaols, prisoners in stockades provided labour while serving their sentences, as it was hoped this would help recover some of the cost to the government of the large-scale penal establishments it was forced to maintain. In the case of Collingwood Stockade, the proceeds from its prison labour almost funded the entire running of the gaol.[3] Prisoners at the stockade were generally involved in quarrying and cutting bluestone for roads and kerbing. Basalt was found to a depth of ten metres in the vicinity of the stockade, and this meant that hundreds of men could be employed for many years quarrying the stone. The demand became so great for its bluestone that by November 1854 the Collingwood Stockade had been extended to accommodate three hundred men, in order to increase the output from its quarries. This increase in demand was a result of an agreement made between the City of Melbourne, the owners of the quarries, and the Penal Department, that labour, as well as the cost of cartage of the stone to Melbourne, would be charged at twenty-five per cent less than free labour.[4]

As well as roadworks, the stone was also used for building purposes, with bluestone from the stockade quarries being used to construct some of the early buildings in Melbourne. Stone quarried at the stockade was regarded as superior to that supplied by free labour.[5] The stone cut for building purposes was often used in Penal Department buildings. In 1857 stone was being quarried at the stockade for the new buildings at Pentridge Prison and in 1859 stone was being cut and chiselled for the stockade’s new Governor’s House and ten stone solitary confinement cells.[6] It is also likely that bluestone quarried at the stockade was used to build parts of the Old Melbourne Gaol.

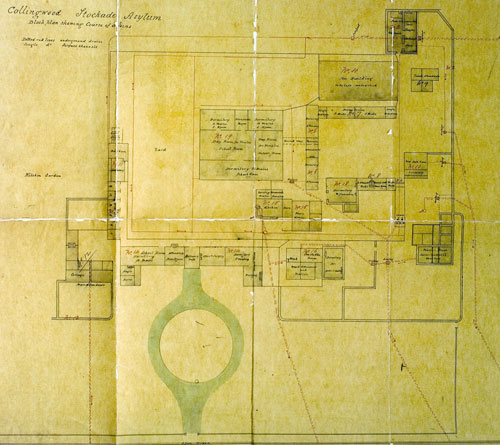

Initially, the majority of the Collingwood Stockade buildings were timber and iron, which indicates that it was the government’s intention that the establishment was to be a temporary measure. A timber palisade fence three metres in height was the only element separating the prisoners from the outside world, but this was later replaced by a bluestone wall after a series of escapes: the first occurring a month after the stockade’s opening. The lax security at the prison was highlighted in 1855 when a former inmate, William Bateman, broke into the prison: the purpose of his visit being to conspire with inmates to execute an escape![7]

The majority of the prisoners were accommodated in dormitories. This type of accommodation was outdated, if not primitive, even for the mid-nineteenth century, as it was seen by this time to hamper the reform of prisoners. Housing prisoners in cells was viewed as a better method of maintaining discipline in several ways. In the 1840s, widespread homosexual behaviour amongst prisoners on Norfolk Island and Van Diemen’s Land was blamed on dormitory accommodation. A public scandal erupted, embarrassing penal authorities on both islands, which led to the introduction of cells in both places.[8] At least ten cells were made available at Collingwood Stockade in 1859 for prisoners whom it was ‘advisable to separate by night from their companions’.[9] Other misdemeanours at the stockade ranged from insolence, refusal to work and, in one unusual case, a prisoner walking on the breakfast table.[10]

At any given time, a significant proportion, on average fifty, of the stockade’s total inmates were Chinese.[11] It had been the practice in the Colony’s gaols to house Chinese prisoners separately, as it was believed that group accommodation would help to prevent the high incidence of suicide amongst them.[12] Another factor contributing to the practice of separating Chinese prisoners from the rest of the prison population at night would have been concern for their safety, given the record of violence towards them on the goldfields and the practice there of separating Chinese camps from others. A Lin was typical of Chinese prisoners at the stockade. He arrived in Victoria in the early years of the gold rush, as a single young man, with no relatives in Victoria and probably a limited social network. He soon found himself in trouble with the law, and without the ability to read, write or speak English, there was little hope that he would receive a fair trial. A farmer by trade, Lin was imprisoned for six months at the stockade for robbery.[13]

PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 696, School No. 1252 Carlton, Lee St.

Although the Chinese made up the greatest proportion of non Anglo-Celtic prisoners, the ‘Register of Names, Particulars and Personal Descriptions of Prisoners’ held at Public Record Office Victoria indicates that many prisoners arrived from all corners of the globe, reflecting the cultural diversity of gold rush era Victoria.[14] Prisoner James Bafrett, who is described as a ‘Negro’, with ‘ears pierced’, originated from Bermuda. Other men had arrived in the Colony from Buenos Aires, New York and Berlin. Some Aborigines from Sydney were also amongst the list of inmates in the Collingwood Stockade. The stockade register shows that the majority of the inmates’ crimes were minor in nature, with some of the more unusual offences ranging from stealing a pair of boots, to, in the case of John Nash, a former soldier of the 40th Regiment, attempting to commit bestiality.[15]

Religion was an important part of the routine in the stockade. Religious instruction was provided for Christian prisoners on Sundays, as they were not required to work on this day. Similarly, Jewish prisoners, numbering five at one stage, were excused from work on their Sabbath (Saturday). This was a result of the efforts of members of the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation who convinced prison authorities to allow Jewish prisoners to observe their Sabbath. Despite these efforts, government authorities were still refusing special dietary allowances for Jewish prisoners in the 1870s.[16] Other degrees of morality were imposed on the prisoners: swearing, lewd conversation and smoking were strictly forbidden.

Two buildings of note at the stockade were the Prisoners’ Mess and the Governor’s House, which survived on the site well into the twentieth century and were later used by the Lee Street Primary School. The Prisoners’ Mess, which incorporated a schoolroom and chapel for the inmates, was one of the earliest buildings of the stockade. It was constructed of timber and iron and was used as the school’s shelter shed until the 1920s, when it had fallen in to such a state of disrepair it was demolished.[17] The Governor’s House, which comprised a parlour, three bedrooms, a small kitchen and outbuildings, later became the school principal’s residence and was demolished in 1913 after it had also fallen into disrepair.[18] A stone tablet from the Governor’s House is now fixed to the wall of a school building. It reads:

Anno Domini MDCCCLIX (1859)

H.M.S. (Her Majesty’s Stockade)

T.M.S. (Thomas Malcolm Smith, The first Governor)

Carved into the stone, circling this inscription, is what appears to be a convict’s belt.

Photograph © Peter Barrett.

Officers’ Quarters were located to the west of the Governor’s House. They were constructed of bluestone and the building was seven metres by five and a half metres, and three metres high; with a floor described as being level with the ground. Adjacent to this was another stone building, described as a cottage. A set of cells, completed in mid-1859, is of interest, as they were built underground. Their bluestone walls were discovered in works on the school site in recent decades. Prisoners in solitary confinement were housed in these, which had no light and were described by a former warder as akin to being ‘buried alive’.[19] Another large building at the stockade was the dormitory for Chinese prisoners.

Prison reforms led to the closure of Collingwood Stockade on 5 March 1866, when the remaining inmates were transferred to Pentridge. For its last six years it had a large Chinese prison population, and it seems the stockade was used as a depot for housing Chinese and non Anglo-Celtic prisoners. Of the total number of prisoners received in 1860, 218 were described as ‘white’ and 141 were described as ‘black’ (this included Chinese). At the time of closure, forty-two of the seventy-two inmates were Chinese.[20]

PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 696, School No. 1252 Carlton, Lee St.

After the Collingwood Stockade closed, its buildings were converted into an asylum for the reception of ‘lunatics’ transferred from Melbourne gaols. This institution, the Collingwood Stockade Asylum, existed until 1873, when the site was converted to its current use as a primary school to cater for the children of the suburb that was developing around the former stockade site. Bluestone salvaged from stockade buildings was used for the footings and flaggings of the 1878 primary school building. This bluestone, and the stone tablet from the Governor’s House are, sadly, the only visible physical remains of this significant part of Victoria’s early prison history.[21] They are a reminder of the hundreds of inmates held at the Collingwood Stockade, who, with their diverse range of cultural backgrounds, were a precursor to the rich array of backgrounds that make up the North Carlton community today.

Endnotes

[1] HA White, Crime and criminals, or, reminiscences of the Penal Department of Victoria, Anderson Berry, Ballarat, 1890, pp. 21-2 & 24.

[2] PROV, VPRS 688/P0 Letter and Memoranda Book, Inspector General’s Office to the Superintendent, Collingwood Stockade, Units 1 and 2, 1853-1856; P Lynn and G Armstrong, From Pentonville to Pentridge: A history of prisons in Victoria,State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, pp. 41-2.

[3] White, Crime and criminals, p. 114.

[4] Chief Secretary’s Office, Annual Report of Penal Establishments, Parliament of Victoria, 30 June 1855, p. 6.

[5] ‘Collingwood Stockade’, Argus, 10 May 1859.

[6] DG O’Donnell, ‘The Story of Australia: Early Victoria’, Gisborne Gazette, 5 July 1935; ‘The Collingwood Stockade’, Argus, 7 January 1860.

[7] V Pratt, Passages of time: a history of Lee Street State School and its site from 1853, V Pratt, North Carlton, 1981, p. 11; Melbourne (Morning) Herald, 23 March 1853.

[8] JS Kerr, Out of sight, out of mind: Australia’s places of confinement, 1788-1988, SH Ervin Gallery, National Trust of Australia (NSW), Sydney, 1988, pp. 57-8 & 61-2.

[9] Chief Secretary’s Office, Report of the Inspector General of Penal Establishments, Parliament of Victoria, 26 October 1859, p. 4.

[10] PROV, VPRS 690/P0 Superintendent’s Record Book, Unit 1 (1859-1865).

[11] Chief Secretary’s Office, Annual Report(s) of Penal Establishments, 1857-1866, Parliament of Victoria.

[12] Lynn and Armstrong, From Pentonville to Pentridge, p 69.

[13] PROV, VPRS 10934/P0 Register of Names, Particulars and Personal Descriptions of Prisoners, Unit 1 (1856). Please note that subsequent to this research being undertaken in the 1990s, this record has now been closed for preservation reasons (under Section 11 of the Public Records Act 1973).

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] LM Goldman, The Jews in Victoria in the Nineteenth Century, Goldman, Melbourne, 1954, p. 223.

[17] Argus, 10 May 1859; Gisborne Gazette, 5 July 1935; Carlton, Lee St, School 1252, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Units 696 and 697.

[18] Gisborne Gazette, 5 July 1935; Carlton, Lee St, School 1252, PROV, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Units 696 and 697.

[19] Gisborne Gazette, 5 July 1935; Argus, 30 December 1856.

[20] Penal Establishments and Hulks, Statistics of the Colony of Victoria for the year 1866, part IV, Law, Crime etc. in papers presented to parliament, first session, 1867, vol. 5, Government Printer, Melbourne, p. 1143.

[21] Foundations of other buildings of the stockade are still extant under the grounds of Lee Street Primary School.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples