Last updated:

‘Court records and cultural landscapes: Rethinking the Chinese gold seekers in central Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Keir Reeves and Benjamin Mountford.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article examines the Chinese goldseekers and the historical mining landscape of central Victoria in the context of the locality of Vaughan Springs, situated along the Loddon River in the central Victorian goldfields. The article uses a close reading of legal records and contemporary newspaper and mining wardens’ reports to explore the experiences of the region’s Chinese community. This approach aims to uncover both the nature of Chinese experiences on the diggings and the complexities of an emergent goldfields culture during the gold rush era. By synthesising primary source archival documents with the relic mining landscape of the Mount Alexander diggings, this article seeks out new understandings of Chinese cultural life and practice in the region.

Cultural Landscapes reflect the interactions between people and their natural environment over space and time. Nature, in this context, is the counterpart to human society; both are dynamic forces, shaping the landscapes.[1]

Photograph © Ben Mountford 2006.

In August 2006 a research team from the University of Melbourne set out across country Victoria in pursuit of the Golden Dragon.[2] The purpose of the field trip was to interpret historical locations relating to the Chinese in Victoria and to evaluate cultural landscape analysis as a tool of historical inquiry. Cutting a path across the state, the group examined sites ranging from the highly interpreted Gum San Centre in Ararat and Golden Dragon Museum in Bendigo to the remnant mining landscape of Vaughan Springs and the Chinese Graveyard in the Buckland River Valley.[3]

The field trip confronted the complexities of exploring cultural landscapes and raised a number of questions that form the basis of this article. How could landscape analysis and documentary investigation be synthesised in order to reveal new historical interpretations of the colonial gold rush era? How might the group attempt to unpack distinctive landscapes set across more than a thousand kilometres of the Victorian countryside? What relationship would new cultural approaches have to the world of archival research, which participants were proposing to step outside of, both physically and conceptually?[4]

Photograph © Keir Reeves 2003.

The first stop on the Heritage Workshop field trip provided a reflection on established practice. Supported by the research of the Ararat Chinese Heritage Society, the Gum San Chinese Heritage Centre ‘bring[s] to life the history of the immigrant miners of the Victorian Goldfields in the late 1800s’.[5] The centre uses historical re-enactment, interactive displays and interpretive text panels to guide the visitor through its circular exhibition space.[6] Like much of the recent historiography of the Chinese in Victoria, Gum San weaves together a core selection of documents and images, to reconstruct the experiences of communities and individuals.[7] In challenging the traditional omission of ethno-historical perspectives in Australian history, Gum San mirrors academic attempts to seek out Chinese Australians through the fragments of evidence in which colonial society documented their existence.[8]

In recent years, historians of the Chinese in Australia have sharpened their focus, directing their efforts towards more detailed investigations of communities and locales. These studies are creating new ‘geographies of knowledge’, which enrich our understanding of Chinese Australians and offer fresh insights to nuances and regional variations in the nature of cultural exchange.[9] The most innovative and illuminating of these histories have adopted complementary approaches, synthesising traditional archival research, material culture studies and spatial investigations. Constructing ‘ethnographic collage[s]’, these works marry rigorous documentary analysis and cultural investigations to fashion new and evolving historical methodologies.[10] These advances in Chinese-Australian history as a discipline have pointed to a number of avenues for the exploration of Victoria’s relic mining landscapes and the Chinese on the diggings.

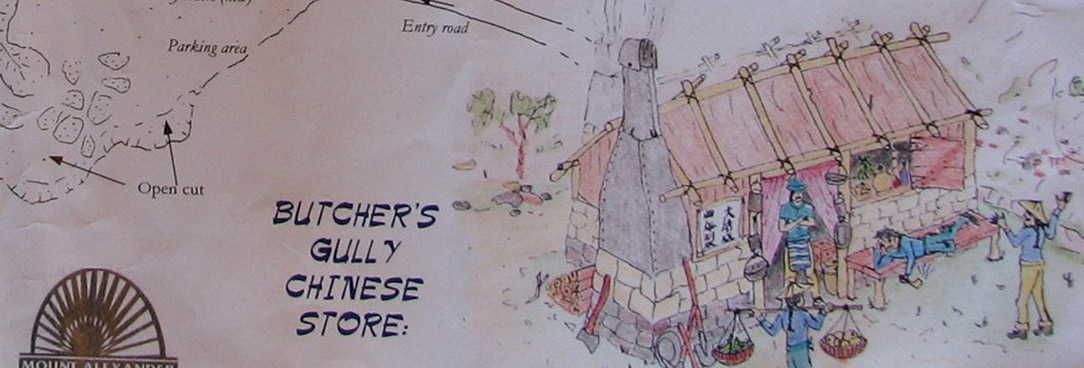

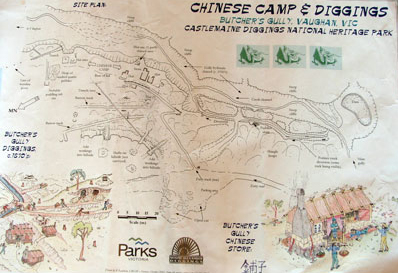

A tangible and immediate expression of these new opportunities for investigation can be found at the Chinese village at Butcher’s Gully, Vaughan Springs.[11] In the fading grey light of a winter’s evening or the bright sunny haze of an August morning, Vaughan’s landscape broods with a sense of significant human traffic, long since departed.[12] The tranquil bush setting which characterises the area masks a history of bustling activity, of market gardening, of produce, trade and small teams of European and Chinese diggers working in close proximity on alluvial claims.[13]

Reproduced with the kind permission of Mr Rob Kaufman of LRGM services and Parks Victoria.

This remnant mining landscape, dotted with evidence of prior habitation and the ruins of the Chinese village, has been gradually reclaimed by nature as human impact has waned. Despite the encroachment of the bush, however, the remains of clay jars, solid buildings, diggings and agriculture, all attest to the area’s vibrant past.[14] Taking this cultural landscape and setting it as a framework for historical exploration, we can begin to unpack the complex history of this idyllic setting. Vaughan’s Chinese inhabitants have left behind a network of interweaving historical trails, both paper and physical, through which it is possible to ascertain some sense of the day-to-day life of the Chinese on the Loddon. Here, a complementary approach that considers impressions left in both the landscape and the archive facilitates the development of a more complex history of the Vaughan Chinese than would otherwise be possible.[15]

Given the diversity of questions and the selection of sources available for studies of the Mount Alexander diggings in general and Vaughan in particular, the most useful approach for this article is to utilise different but overlapping methodological approaches.

This article uses a number of alternative sources of information to develop an historical account of the Chinese on the Mount Alexander diggings during the second half of the nineteenth century. There are the conventional archival records that consist mostly of government edicts and newspaper articles that largely focus on court summaries.[16]

There are a number of archival series that have not been previously examined, consisting mainly of unpublished locally-produced histories, contemporary locally-printed anti-Chinese pamphlets, land files and council records. This information is of a high quality but is limited in quantity. This is particularly true when seeking a more sophisticated understanding of the goldfields Chinese in Victoria, a group who seemingly disappeared into the historical ether according to existing histories of the diggings and conventional modes of historical enquiry. This omission is compounded in the broader community where the common understandings may include a simplistic description of the nineteenth-century Chinese, notwithstanding the efforts of organisations such as the Museum of Chinese Australian History in Melbourne, the Golden Dragon Museum in Bendigo, the Gum San Chinese Heritage Centre in Ararat and the Chinese Heritage of Australian Federation Project.[17]

The objective of our approach is to reconcile competing sources into a cohesive methodology that presents the reader with a multiplicity of linked approaches with which they can interpret the history of the Chinese in and around Vaughan. A particularly useful government source is the historical survey maps of the Victorian Geological Survey; these reveal a great deal of cadastral detail for the nineteenth century, particularly in regard to the southern regions of the diggings.[18] Information regarding land usage and cultural meaning embedded within the cultural landscape complements the information gleaned from geological maps and the archival records. In seeking out new understandings, we have set out to synthesise these different historical sources in order to construct a more comprehensive historical account.

In doing so, this paper also aligns itself with more recent attempts to weave together Chinese-Australian histories from surviving, but often disjointed, shreds of documentary evidence.[19] This approach has enabled historians to move beyond a history built around faceless statistics to a more meaningful expression of individual and collective experience.[20] It has also facilitated a more sophisticated exploration of Chinese communities and the multi-dimensional lives of some key characters.[21] In these histories, court documents and records generated in the dispensation of colonial justice provide valuable source material.

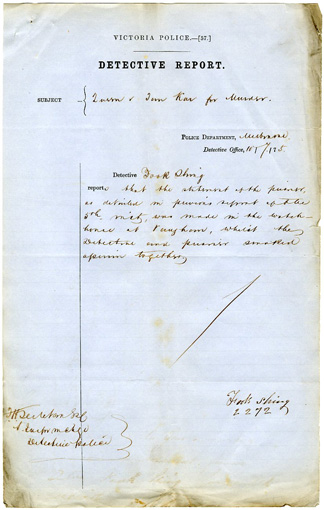

Police court records offer the researcher the ability to examine long-term trends relating to Chinese involvement in petty crime, to interrogate assumptions about relations with police and the wider community and to piece together the circumstances of repeat offenders.[22] Criminal trial briefs for capital crimes often contain statements translated and transcribed directly from Chinese-speaking prisoners and witnesses, as well as information on the community and lifestyle of the defendant and victim.[23] In addition, both sources shed light on the boundaries of acceptable behaviour and express regional variations in the frequency and character of court proceedings.[24] Archival research into the Chinese at Vaughan suffers from a dearth of court sources. The records of the Vaughan police court have apparently been destroyed and the documents which survive from the only capital case involving two Chinese at Vaughan are fragmentary.[25] Despite these limitations, however, there are avenues of exploration relating to the maintenance of law and order which complement an analysis of the remains of Vaughan’s Chinatown.

On 30 August 1875 An Gaa (sometimes Ah Gaa, sometimes Tan Kar), a Chinese miner who had arrived in Victoria from Canton Province in 1857,[26] went to the gallows in Melbourne Gaol having been found guilty of the murder of Pouey (sometimes Povey) Waugh.[27] A dramatic murder case in which Vaughan Chinese were cast as both defendant and victim, The Queen vs An Gaa received significant attention in the local press and in the Melbourne newspapers.[28] While the surviving case records are disjointed and incomplete, the evidence that remains does offer a glimpse into the day-to-day life of An Gaa and his companions at Vaughan before their relationships took a more sinister turn. From the statement provided by Chinese detective Fook Shing[29] and through contemporary newspaper accounts, we can discern that An Gaa shared a windowless bark hut with his mate Pouey Waugh.[30] The pair slept on simple bunks consisting of ‘forked saplings let in the ground [with] a cross sapling put in the forks and a few boards lying on them; these being covered with straw’.[31] This form of dwelling was seemingly the norm for the Vaughan Chinese in the 1870s. The Mount Alexander Mail (the most extensive local chronicle of diggings life) described the village near the junction of the Loddon and Fryers creek as consisting of a series of bark huts and a stone-built store.[32] An Gaa had discovered what Fook Shing surmised as a reasonably profitable claim[33] and allowed Pouey Waugh and two other mates, Ah Chew and Ah Ho, to work on the claim for a ten per cent commission on all gold they found.[34] For obvious reasons of security and convenience, An Gaa had established his home in close proximity to his claim, so close that as he lay in bed on his day off he could hear his mates washing gold outside.[35] This description of Chinese miners on the Loddon working together in groups of three to five and cohabiting in pairs corresponds with the living arrangements described in the trial of Ah Pew from nearby Glenluce some five years earlier.[36]

Photograph © Ben Mountford 2006.

The layout of the ruins of the Chinese village at Vaughan as they exist today reaffirms the cultural life and practices described in the court documents above. Ruins at the site might be described as the remains of small dwellings (principally the foundations of walls and the hearth), just large enough for comfortable twin or triple habitation, huddled in congregations along the Loddon. A site survey of the Chinese village reveals remnant water course systems,[37] disused shafts and scattered mounds of discarded debris all occurring in close proximity to the structures that have been unearthed. Also scattered through the area, though concentrated near structural ruins, are botanical records of Chinese habitation such as wild spring onions.[38] By immersing ourselves in these aspects of the archaeological record, the researcher can begin to explore a history beyond statistics and figures.[39] Visiting the village at twilight one hundred and thirty years after An Gaa described his day-to-day life to Fook Shing, it is not difficult to visualise the contemporaries of An Gaa and Pouey Waugh going about their daily business. Working together side by side on the claim during the day, vulnerable to all the usual frictions and jealousies that come with financial inequity and shared workspace, they would return home together to complete domestic duties, prepare a cooked meal and collect enough firewood to stave off the cold of the Victorian winter.[40] The weary miners would then smoke a few pipes of opium and retire before resuming their labours the following morning.[41]

PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875.

In addition to unveiling these more intimate aspects of life on the Loddon, the documentary fragments which emerge in The Queen vs An Gaa also shed light on communal impact on the cultural landscape at Vaughan. Interpretation of scattered Chinese pottery remnants, for example, is more achievable with reference to the accounts of men like Ah Hung and his contemporaries.[42] A witness at An Gaa’s trial, Ah Hung was a storekeeper at Vaughan who in addition to providing regular consumables distributed Chinese medicine to members of the community along the Loddon.[43] At least one of Ah Hung’s patrons had also offered his custom to the Campbell’s Creek store belonging to Shee Toy and to the hawker Fong You. This suggests the existence of reasonably sophisticated and competitive commercial culture in the area.[44] This suggestion is reaffirmed by the range and variety of clay vessel fragments discovered across a wide area of the Vaughan Springs site. In a similar vein, unpacking elementary remains of weirs and crossing points on the Loddon and its tributary creeks, can be enhanced when considered in tandem with the brief textual glimpses we find of men like Sing Lee. According to the Mount Alexander Mail, Sing Lee, a miner whose hut lay near the junction of the river and Kangaroo Creek, had established a simple creek crossing made of planks which could be utilised by members of the community, but which he monitored and maintained on their behalf.[45]

Following this complementary approach, using archival records to populate a reading of the cultural landscape, life for the Chinese at Vaughan seems romantically rustic, yet at times bustling and complicated.[46] Surrounded by a number of smaller Chinese enclaves, Vaughan Chinatown was an obvious point of social interaction as well as trade within the Chinese community.[47] But Vaughan was undoubtedly also the scene of great hardship. By 1870, after the final burst of gold rush activity in central Victoria, both the number of Chinese in the colony and those employed in mining had significantly declined.[48] Those who remained often lived a life of precarious economic survival, banding together in small groups with little community support.[49] Reverend Young’s 1868 report into The Chinese Population in Victoria, had found ‘Chinese miners hav[ing] very hard times of it … some barely earn[ing] their food, and some get[ting] nothing’.[50] What evidence might be found to take us beyond Young’s stereotypical depiction of the shabby Chinese miner, eking out a living from the already well picked over soil? It is the impressions of everyday life written in both the landscape and in the records that speak to the more complicated realties of life at Vaughan after the rush.

On 31 August 1875, the day after An Gaa had been buried within the walls of Melbourne Gaol,[51] The Castlemaine Representative published a piece titled ‘Castlemaine As It Is [From an outsider’s point of view]’. Having not visited the area since 1852, ‘The Outsider’ gave his account of the region:

I must confess I hardly expected such changes. I could not recognise the place at all … If any one at all was at work [on the diggings] it was only a few Chinese, who, judging by their wretched appearance must be scarcely obtaining enough to keep body and soul together.[52]

While these sorts of accounts may have included reference to the Chinese on the Loddon, few records have been uncovered which specifically speak of the hardships experienced by the Chinese at Vaughan. One collection of readily available sources which reflect the more extreme cases of adversity are the inquest records held at Public Record Office Victoria. Between 1857 and 1890 the deaths of sixty-six inhabitants of Vaughan were subject to inquest.[53] In thirty-eight of these cases the deceased was either explicitly classified as Chinese or had a name that suggests Chinese heritage.[54]

Unsurprisingly, the inquest records for Vaughan reveal that the hazards associated with mining were the most common cause of death for the period. Eleven of the thirty-eight Chinese deaths were caused by mining accidents such as ‘fall of earth’ and another six were attributed to respiratory problems. Five deaths in this period were attributed to either causes unknown or ‘debility’. The remaining inquests document some extreme instances of more general hardships experienced in the Chinese village. These include starvation and malnutrition (two cases); suicide (three cases); gastrointestinal problems (three cases); heart disease (three cases); drowning (two cases); severe burns (one case); ruptured bladder (one case); and, in Pouey Waugh’s case, murder.[55] Future examination of these individual records may open new pathways of analysis and help facilitate the development of a broader cultural history of the region.[56]

While inquest records suggest that life for the Chinese on the Loddon could be difficult, other documentary sources hint at the dynamics of cultural interaction which took place at Vaughan. It should be noted that cultural exchange on the diggings was typified by misunderstandings on all sides. These included the perceptions of Chinese, many of whom regarded the European miners pejoratively as barbarians — inferior and uncivilised.[57] The close-knit social relations amongst the Chinese communities in some instances precluded the need to engage with the broader community.[58] These close ties were maintained in Victoria by membership of community organisations such as the See Yup Society that reinforced kinship and provided important social welfare and cultural events.[59]

As Goodman has noted, what both humanitarian and racist Europeans found unacceptable was not ‘any particular set of practices and beliefs, but the threat they saw in a self-contained community, one which was not open to the enquiring, judging, governing gaze of the community’.[60] The grass roots actualities of land holdings, business links and personal relationships contradict this, the Mount Alexander diggings’ Chinese being widely engaged with the broader community. Notwithstanding this situation, it could be argued that the arbitrary and ultimately unsuccessful separation of the Chinese from the broader mining group was conceived and implemented by the colonial authorities and prior to this and afterwards Chinese and Europeans cohabited within certain areas of the diggings.

This contact between Europeans and Chinese was complicated and governed by proximity and interdependence. Antagonism and racism played a part, ‘but this racism was challenged by the close-knit circumstances of daily life’.[61] On 30 March 1864 The Mount Alexander Mail acknowledged the importance of Chinese market gardeners in ensuring adequate food supplies.[62] Evidence of the interweaving of European and Chinese lives along the Loddon is scattered throughout the archive. In 1870, at the trial of Ah Pew from Glenluce, it emerged that the prisoner had been for years supplementing his mining income by doing odd jobs for local Europeans. Not only did Ah Pew and his mates speak very good English, but he was described by several European witnesses during his trial as being of ‘good character’.[63] This type of cultural interaction is often overshadowed by newspaper hyperbole emphasising racial tension and taking the arbitrary line that goldfields Chinese were separated by language and therefore occupied ‘an isolated position in the community’.[64] Conversely, it seems that contact could be fairly common, affable, and was not necessarily based on impersonal commercial exchange.[65] Heather Holst’s analysis of the police court records for Castlemaine, Fryerstown and Chewton suggest that despite obvious instances of prejudice, Chinese men could expect a certain degree of fairness when appearing at court in the region and were at times supported by their European neighbours in resisting legal injustices.[66]

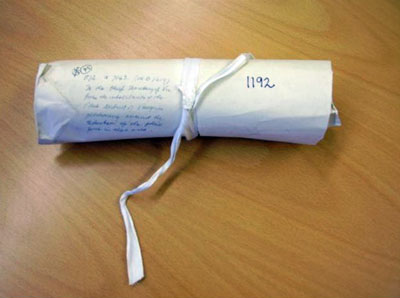

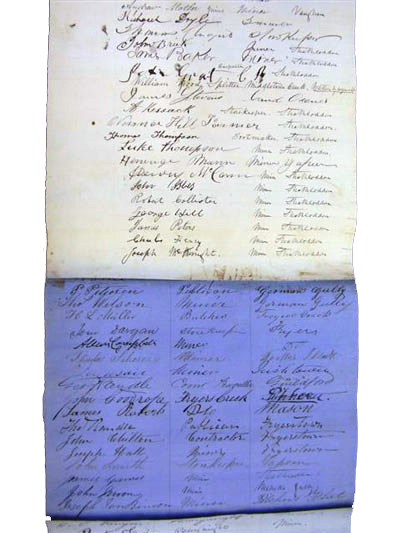

PROV, VPRS 1192/P0 Petitions, Unit 45.

While sadly a similar investigation at Vaughan has been rendered impossible by the apparent destruction of police court records, one rare archival document that has survived is the 1872 petition from ‘the Inhabitants of the Police District of Vaughan’.[67] Stretching over three metres long, this beautifully preserved document captures community resistance to a proposal to reduce the number of local constables from two to one. The petition might be read on a number of levels. Most immediately it is an outpouring of local concern at a perceived bureaucratic bungle made in Melbourne which would ‘undermine the police protection afforded for about fourteen years’.[68] But in addition to this, the document is an expression of the paranoia suffered by some of Vaughan’s European residents about a lurking evil, which might engulf the area should police presence be halved. Both registering a grievance and offering an introduction to the district, the memorialists began their petitioning of the Chief Secretary with a description of the area:

The said district contains an area of twenty square miles with a population of 2500. It is essentially a gold mining district with an unusually large number of Chinese — and fifteen public houses scattered throughout the district.[69]

Committee Secretary WH Wilson, having obtained over ten pages of signatures and resolutions of support from the Shire Councils of Newstead and Mount Alexander, warned the Chief Secretary that:

Your memorialists are fully convinced that it would be unreasonable to expect a single policeman to preserve the peace, order and security of the district and that should the reduction be carried into effect it will so embolden the evil disposed who have hitherto been kept in check, that a very large increase of crime must inevitably ensue.[70]

It is not explicit but there is a suggestion in the tone of the document that a significant proportion of the ‘evil disposed’ might be Chinese. The size of the district and the ‘unusually large number of Chinese’ are presented as demonstrating the need for two dedicated constables. Memorialist insecurities, however, are multi-dimensional and go beyond racist suspicion. The landscape around the site of the Chinese village at Vaughan, while beautiful, is rugged and unyielding. Steep gullies, inaccessible river banks and cliffs define the topology of the area along the Loddon River.[71] In addition to a nervousness about the underlying character of their Chinese neighbours, the petitioners also express an anxiety about their natural surroundings:

The difficulty of access to many of the gullies and ranges of the district, which formerly afforded a favourite resort to many lawless persons – there has lately been a remarkable freedom from offences in the district due apparently to the work of the two constables in the prevention as well as the suppression of crime.[72]

The landscape of the district is cast as conducive to wrongdoing. To the residents represented in the petition, active policing kept at bay the ‘evil disposed’ in the community and countered a propensity to evil written in the landscape itself. Visiting the ruins of the Chinese village at Vaughan today and standing in the sheltered gully along the Loddon, surrounded by fast falling shadows, it is tempting to speculate from the remains of closely huddled dwellings that the Vaughan Chinese shared this apprehension about their natural surroundings with their European neighbours.[73]

If the ‘Petition of the Inhabitants of the Police District of Vaughan’ embodies a certain set of community anxieties, a more sophisticated glimpse into local race relations in the 1870s is facilitated via a close reading of a sequence of dramatic events that took place in November 1874. At two o’clock in the morning of 11 November, Vaughan’s residents awoke to an extensive fire which had broken out at Richards’ wholesale and retail store. A local reporter was soon on the scene. The next day his gripping eyewitness account appeared in The Mount Alexander Mail and was also picked up by The Argus:

The flames spread with a rapidity which it was impossible to check … many willing hands presented themselves, for all the residents were aroused from their slumbers, but to do more than guard against loss of life was utterly impossible.[74]

PROV, VPRS 1192/P0 Petitions, Unit 45.

As residents accounted for each other, unable to subdue the raging fire, flames leapt via the timber yard adjoining to the Chinese Camp, which consisted of about thirteen closely packed wooden structures:

About three or four tons of rice were dragged from … Ah Jack’s and put on the bridge leading across the stream to Tarilta, but even at that distance it was only kept from smouldering by applying wet blankets. The Chinese from the first exhibited their belief in fatalism, by merely saving themselves, and standing outside in the road chatting and gesticulating. An attempt was made by the Europeans to save a little of their property, but the attempt was futile — each house, with the exception of one Chinese store, being of flimsy weatherboards.[75]

That the Europeans on the scene attempted to save the Chinese village suggests the existence of a functioning interracial community at Vaughan, which the reporter, in moralising on Chinese depravity, failed to register. The invective against the Chinese and their homes ‘so small that no one could venture into them for the stench of burning oil, opium, and worse’, can’t eclipse the image, albeit glancing, of Europeans at Vaughan attempting to save the property of their Chinese neighbours against the dramatic backdrop of a shared local tragedy.[76]

Similarly, the financial fallout of the fire impacted on European and Chinese store owners alike. Mr Richards’ £1,100 insurance policy would not nearly cover the damage done while storekeeper Ah Jack was insured for just over £500.[77] The unfortunate Gun Yeck, a Chinese man who had recently married, ‘lost £43 in notes, and such was his suicidal desperation’, that he wished to remain in the house, and had to be dragged out by his hair by the Europeans.[78] Regardless of their race, residents were faced with the prospect of disaster, the loss of a home and in some cases a livelihood. Parts of Vaughan had completely gone up in smoke and it is not hard to visualise the chaos of the scene on that spring morning as flames spread around the enclosed gully. Approximately fifteen dwellings and all their contents were utterly consumed, ‘only seven chimneys and smouldering debris mark[ing] the spot where a very considerable portion of Vaughan [once] stood’.[79] Rather than offer consolation or support from a distance, ‘to the extent of their ability, the [European] residents accommodated the Chinese temporarily, and many … found refuge in the concert-room at Belot’s Hotel’.[80]

This sense of an interracial community at Vaughan is reflected in the experiences of the Chinese-European Hoyling and Jacjung families. Associated with the township for much of the second half of the nineteenth century, members of these two families were deeply involved in a range of local activities.[81] Ham Hoyling, a storekeeper, hotelier and market gardener, and Lee Heng Jacjung, an interpreter, businessman and market gardener, prospered financially and as successful businessmen were integrated into the European community.[82] Their stories reinforce the view that personal connections and local cooperation often challenged more general undercurrents of racial prejudice and exclusion. As one local historian, drawing on his own childhood memories, has pointed out, despite an exodus of Chinese miners following the rush, ‘some of the diggers stayed on to live on the goldfields after the gold had finished, and remained there until their final rest’.[83] Those who remained in the southern reaches of the Mount Alexander diggings, in and around Vaughan, continued as integral members of the community until the early twentieth century.[84]

Photograph © Ben Mountford 2006.

A year after the blaze which had devastated the Chinese village, the scourge of fire once again returned to Vaughan. This time, however, in an act of spectacular bravery, a constable by the name of King plunged into the river and facing grave personal danger cut down the fences which would have led the fire to the rebuilt Chinese village.[85] We would speculate that these were not the actions of a man just doing his duty. A European policeman seriously risking his life to save the homes of his recently devastated Chinese neighbours speaks more of common experience, shared lives and a sense of community in times of adversity than of frontier chauvinism and racial division. As more of these vignettes about Vaughan town life are unearthed, the population of the cultural landscape and the subsequent unveiling of a history of the Chinese at Vaughan through complementary methods of historical inquiry will hopefully continue.

These local impressions and the links between them offer the opportunity to enrich Chinese-Australian histories and complement available archival records from the bottom up.[86] The history of the Chinese on the Loddon is clearly complex and sophisticated. An attempt to uncover hidden histories at Vaughan demonstrates how new avenues of exploration emerge when cultural landscape analysis and traditional research are employed in tandem. This complementary approach promises new insights and understandings for historians in search of the Chinese experience on the central Victorian goldfields. A key purpose of the article has been to reinstate the Chinese into local histories of the Mount Alexander diggings. The main thrust has been to emphasise the multifaceted nature of cultural life on the diggings. By teasing out this cultural complexity and explaining it in conjunction with other approaches to understanding the era, it is possible to present a more balanced and layered impression of the Chinese on the diggings during the nineteenth century.

Endnotes

[1] B von Droste, H Plachter and M Rössler (eds) Cultural landscapes of universal value, Gustav Fischer, Jena, Germany, 1995, p. 15.

[2] This field trip was undertaken as part of ‘Chinese Heritage Workshop’, a University of Melbourne fourth-year history seminar.

[3] F Links and S Lawrence, ‘Geophysical investigation of a 19th century Chinese cemetery, Buckland, Victoria’ University of Tasmania, Hobart, and La Trobe University, Melbourne, 2004, pp. 2-3.

[4] B Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Ararat, 18 August 2006.

[5] ‘History’, taken from the Gum San Chinese Heritage Centre website, available at http://www.gumsan.com.au/index.php?id=story (accessed 26 October 2006).

[6] Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Ararat, 18 August 2006.

[7] ibid. Sources at the Gum San Chinese Heritage Centre, Ararat, include illustrations, newspaper excerpts, photographs and written documents.

[8] For an exploration of the position of ethno-historical perspectives in Australian history, see B York, Ethno-historical studies in a multicultural Australia, Centre for Immigration & Multicultural Studies, Canberra, 1996, p. 27. Graeme Davison and David Dunstan discuss approaches to fragmentary and distorted sources in G Davison and D Dunstan, ‘This moral pandemonium: images of low life’, in G Davison, D Dunstan & C McConville (eds) The outcasts of Melbourne: essays in social history, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985, p. 23.

[9] A McKeown, ‘Introduction: the continuing reformulation of Chinese Australians’, in After the rush: regulation, participation, and Chinese communities in Australia 1860-1940, Otherland Literary Journal, no. 9, 2004, p. 6.

[10] J Lydon, ‘Many inventions’: the Chinese in the Rocks, Sydney 1890-1930, Dept. of History, Monash University, Clayton, 1999, p. 67.

[11] Located approximately ten kilometres south of Castlemaine, the township of Vaughan was surveyed and proclaimed in 1856, three years after gold was first discovered in the area. By 1857 the population had reached two thousand with a significant proportion of Chinese males. An extensive artificial water supply system had been constructed to serve the mines by the 1870s though in 1891 Vaughan’s population had fallen to twenty-four . See ‘Vaughan, Vic.’ on the eGold website at http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00254b.htm (accessed 3 March 2007).

[12] B Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Vaughan Springs, 18-19 August 2006.

[13] K Reeves, ‘A hidden history: the Chinese on the Mount Alexander diggings, central Victoria, 1851-1901’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2005.

[14] Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Vaughan Springs, 18-19 August 2006.

[15] For a discussion of the importance of material culture studies and historical archaeology as a supplement to archival research in Chinese-Australian studies, see RI Jack, ‘Contribution of archaeology’, in J Ryan (ed.), Chinese in Australia and New Zealand: a multidisciplinary approach, Wiley Eastern, New Delhi, 1995; Lydon, ‘Many inventions’, pp. 19-24.

[16] Most of the records are located at Public Record Office Victoria and many are duplicated at the Castlemaine Historical Society. The most extensive newspaper holdings are located at the State Library of Victoria. One notable publication about the Castlemaine Chinese using legal records is H Holst, ‘Equal before the law? The Chinese in the nineteenth-century Castlemaine police courts’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, vol. 6, 2004, pp. 116-17. Andrew Markus and David Goodman, along with many local historians, have extensively used the Mount Alexander Mail and other local newspapers.

[17] See for example ‘The Chinese Museum tenth anniversary issue 1985-1995’, The Journal of the Museum of Chinese Australian History, no. 1, 1995. The main Chinese- Australian museums and heritage centres in Victoria are the Bendigo Chinese Association Golden Dragon Museum, the Gum San Chinese Heritage Centre at Ararat, the Beechworth Chinese Cultural Centre and the Museum of Chinese-Australian History in Melbourne. Additionally, a number of studies and resources have been produced by ‘The Chinese Heritage of Australian Federation Project’, a joint initiative of La Trobe University, the Chinese Museum and Shanghai’s East China Normal University.

[18] Department of Crown Lands and Survey Victoria, ‘Vaughan Map’, Melbourne,1972. These maps detail the extent, value and ownership of land for taxation purposes. A number are located within the PROV Historic Plan Collection, PROV, VPRS 8168 Historic Plan Collection.

[19] Keir Reeves has recently reconstructed the story of James Acoy from these sources in K Reeves, ‘Goldfields settler or frontier rogue? The trial of James Acoy and the Chinese on the Mount Alexander Diggings’, Provenance, no. 5, September 2006. Key PROV records utilised include the series VPRS 30 Criminal Trial Briefs, VPRS 515 Central Register of Male Prisoners, and VPRS 937 Inward Registered Correspondence. See also K Wong-Hoy, ‘Thursday Island en route to citizenship and the Queensland goldfields: Chinese Australians and naturalised British subjects, 1879-1903’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, vol. 6, 2004, pp. 159-74.

[20] P Fass, ‘Cultural history and social history: some revelations on a continuing dialogue’, Journal of Social History, vol. 37, no. 1, 2003, p. 39.

[21] Reeves, ‘Goldfields settler or frontier rogue?’; R Travers, Australian mandarin: the life and times of Quong Tart, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1981.

[22] Holst, ‘Equal before the law?’, pp. 116-17; G Presland, ‘Detecting Chinese crime in nineteenth-century Victoria’, in J Ryan (ed.) Chinese in Australia and New Zealand.

[23] K Reeves, ‘A songster, a sketcher and the Chinese on Central Victoria’s Mount Alexander diggings: case studies in cultural complexity during the second half of the nineteenth century’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, vol. 6, 2004, p. 2.

[24] Holst, ‘Equal before the law?’, pp. 116-17.

[25] ibid. Holst discovered during her research that the Vaughan police records had been destroyed many years earlier. We discovered during our own investigations that only a limited number of disjointed records relating to ‘The Queen vs An Gaa’ have survived in An Gaa’s criminal trial brief, PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875. For the researcher this contrasts with the dramatic 1870 Castlemaine murder trial of Chinese defendant, Ah Pew, for which extensive documentation is held in this series at PROV. Additionally, An Gaa’s capital case file is not listed in PROV holdings for 1875 (PROV, VPRS 264 Capital Case Files) and the inquest into victim Pouey Waugh’s death was seemingly not filed with An Gaa’s criminal trial brief (as was usually the case for the period 1840 to 1950, when an inquest resulted in criminal charges being laid (PROVguide 71: Courts and Criminal Justice – Inquest Records). A coroners’ slip ‘Proceedings of Inquest held upon the Body of Poosey [sic] Waugh, Vaughan’ indicating that an inquest did take place, can be found at PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 333. An Gaa does have a prison record in PROV, VPRS 515 Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 22, An Gaa; the first ‘Register of Decisions on Capital Sentences’ book PROV, VPRS 7583/P1 Register of Capital Sentences, Unit 1; and his own inquest can be located at PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 329. Brief reference to the trial and surrounding events can also be found in a number of diverse series such as PROV, VPRS 937/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 190, Bundle 1, no number, ‘Detective Report: Detective Fook Shing Travel expenses, Re: Murder at Vaughan, 2/7/75.’

[26] Argus, 31 August 1875.

[27] PROV, VPRS 515 Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 22, An Gaa.

[28] The case appeared in the Argus eight times according to the The Argus Index, available at http://www.nla.gov.au/argus/ (accessed 20 September 2006).

[29] The statement was taken in the watch-house at Vaughan ‘whilst the detective and prisoner smoked opium together’. Report of Detective Fook Shing, 10 July 1875, PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875. Fook Shing was the longest serving Chinese detective in the Victorian Police Force (1868-1886), see G Presland, ‘Chinese detectives’, Journal of Police History, 1994, p. 51. Presland argues elsewhere that ‘The department was more easily able to acquire the necessary evidence through the involvement of a Chinese detective’, G Presland. ‘Chinese, crime and police in nineteenth-century Victoria’ in Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, P Macgregor (ed.), Museum of Chinese Australian History, Melbourne, 1995, p. 379.

[30] Mount Alexander Mail, 20 July 1875.

[31] ibid.

[32] Mount Alexander Mail, 11 November 1874.

[33] Statement of Fook Shing, 5 July 1875, PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875.

[34] Statement of Charles Hodges, Chief Chinese Interpreter, 13 July 1875, PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875.

[35] ibid.

[36] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 370, Castlemaine Circuit Court, Case number 2 of April 1870.

[37] The most prominent is Moyle’s Race built using Chinese and European labour. Today this race forms much of the walking trail of the Vaughan Springs area. See RA Bradfield, ‘A bush walk from Vaughan Springs’, in Bradfield Family Collection, Vaughan, circa 1970, p. 5.

[38] M Amos ‘Appendix C: historical sketch of the Fryers Creek goldfields’, Melbourne circa 1887, in K Reeves, ‘A hidden history’. See also K Reeves, ‘Historical neglect of an enduring Chinese community’, Traffic no. 3, 2003, pp. 62-3; Z Stanin, ‘From Li Chun to Yonh Kit: a market garden on the Loddon 1851-1912’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, vol. 6, 2004, pp. 25-6.

[39] Jack, ‘Contribution of archaeology’, pp. 21-22.

[40] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875. Fook Shing’s and Charles Hodges’ statements list some of the day-to-day activities mentioned by An Gaa as having happened in the course of the days leading up to Pouey Waugh’s murder.

[41] Statement of Fook Shing, 5 July 1875, PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 462, Castlemaine Court of Assize, Case number 1 of July 1875. When asked if he was ill by Fook Shing, An Gaa replied: ‘I have the opium habit very bad and I am cold’. An Gaa also informed Fook Shing that Pouey Waugh was in the habit of smoking several pipes of opium before going to sleep.

[42] Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Vaughan Springs, 18-19 August 2006.

[43] The Castlemaine Representative, 20 July 1875. Ah Hung’s customer base must have extended over a sizeable area as it took Pouey Waugh at least half an hour to walk to the store.

[44] The Castlemaine Representative, 20 July 1875. Material culture, court records and commercial interaction at Vaughan are also examined in Stanin, ‘From Li Chun to Yonh Kit’, pp. 15-34.

[45] Mount Alexander Mail, 20 July 1875. …or failed to maintain. At the trial of An Gaa, Sing Lee admitted heavy rain had recently washed the bridge away. Having not replaced it, he watched as the unfortunate Pouey Waugh waded across the creek where the planks had been.

[46] This approach draws on the methodology of Henry H Glassie, Passing the time in Ballymenone: culture and history of an Ulster community, University of Philadelphia Press, 1982, pp. 793-4.

[47] Reeves, ‘A hidden history’, p. 189.

[48] L Boucher, Unsettled men: settler colonialism, whiteness and masculinity in Victoria 1851-1886, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2005, p. 53. In the decade 1861-71 the number of Chinese employed in mining dropped from 21,161 to 13,374.

[49] K Cronin, Colonial casualties: Chinese in early Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1982, p. 126.

[50] Rev W Young, ‘The Chinese population in Victoria, 1868 VPP 35’ in The Chinese in Victoria: official reports and documents, IF Maclaren (ed.), Red Rooster Press, Ascot Vale, 1985, p. 39.

[51] Argus, 31 August 1875.

[52] The Castlemaine Representative, 31 August 1875.

[53] A search of the ‘Digger Inquest Index’ actually shows 86 inquests for the period, though only 66 records exist. This anomaly can be explained by the fact that some deceased Chinese individuals are listed twice, though their names are reversed, reflecting a wider confusion surrounding Chinese names in colonial society which is replicated official documentation. In the period up to 1 July 1986 an inquest was held if a person died suddenly, was killed, drowned, died whilst a patient, died in prison, was executed, or was a ward of the state who died under suspicious circumstances whilst in state care. See PROV's inquests and other coronial records guide, available at https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/inquests-and-other-coronial-records (accessed 26 March 2020).

[54] Digger Inquest Index Victoria 1840-1985.

[55] ibid.

[56] Fass, ‘Cultural and social history’, p. 26.

[57] A Curthoys, ‘”Chineseness” and Australian identity’, in A Curthoys, LN Chiang & H Chan (eds), The overseas Chinese in Australasia: history, settlement and interactions: proceedings, Interdisciplinary Group for Australasian Studies (IGAS) and Centre for the Study of the Chinese Southern Diaspora, Taipei, 2001, p. 21.

[58] Cronin, Colonial casualties, p. 23; J Ng, ‘The sojourner experience: the Cantonese goldseekers in New Zealand, 1865-1901’, in Unfolding history, evolving identity: the Chinese in New Zealand, M Ip (ed.), Auckland University Press, 2003, pp. 10-11.

[59] M Leong, ‘The role of the See Yup Society in Melbourne and Victoria’, paper presented at the Chinese Heritage of Australian Federation Conference, Museum of Chinese Australian History, Melbourne, 1-2 July 2000.

[60] D Goodman, Gold seeking, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 21.

[61] Reeves, ‘A hidden history’, p. 108.

[62] Mount Alexander Mail, 30 March 1864.

[63] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 370, Castlemain Circuit Court, Case number 2 of April 1870. Sam Hunt (the murdered Annie Hunt’s father) testified Ah Pew spoke ‘very good English’.

[64] Mount Alexander Mail, 24 May 1870.

[65] AJC Mayne, ‘”What do you want John?” Chinese-European interactions on the Lower Turon Goldfields’, Journal of Australian Colonial History vol. 6, no. 1, 2004; AJC Mayne, Hill End: an historic Australian goldfields landscape, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2003; Reeves, ‘A songster, a sketcher’.

[66] Holst, ‘Equal Before the law?’, pp. 130-31 and 135-6.

[67] PROV, VPRS 1192/P0 Petitions, Unit 45, Petition from ‘the Inhabitants of the Police District of Vaughan’.

[68] ibid.

[69] ibid.

[70] ibid.

[71] Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Vaughan Springs, 18-19 August 2006.

[72] PROV, VPRS 1192/P0 Petitions, Unit 45, Petition from ‘the Inhabitants of the Police District of Vaughan’.

[73] Mountford, Field notes in possession of the author, Vaughan Springs, 18-19 August 2006.

[74] Argus and Mount Alexander Mail, 11 November 1874.

[75] ibid.

[76] ibid.

[77] ibid.

[78] ibid.

[79] ibid.

[80] ibid.

[81] Reeves, ‘Historical neglect of an enduring Chinese community’. For a similar example of complex cultural exchange in Sydney see G Karskens, The Rocks: life in early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1998; Lydon, ‘Many inventions’.

[82] J Kehrer, The Ancestral Searcher, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 328-33. This family history provides the best introduction to the Hoyling family and contains the most extensive information based on family holdings and archival research in Australia.

[83] V Hooper, Mining my past: a life in gold mining, Mount Alexander Diggings Historical Text Series, Castlemaine, 2001, p. 10.

[84] Alternatively, Chinese families moved on and established themselves in similar positions in other goldfields communities. During the late 1870s, for example, Lee Heng Jacjung and his family moved to Gippsland following the largely unsuccessful gold rushes to that region of Victoria and again established himself as a market gardener. See S Legge, ‘A farm in the life of. The Department of Crown Lands and Survey Selection Files’, Gippsland’s Heritage Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 1988, pp. 28-31; S Legge, ‘Lee Hing Jacjung’, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, Gippsland’s Heritage Journal, vol. 3, no. 5, 1988, pp. 32-5.

[85] Argus, 5 August 1875.

[86] P Fowler, Landscapes for the world: conserving a global heritage, Windgatherer Press, Bollington, 2004, p. 25.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples