Last updated:

‘"She Had Not a Baby Face": The death of Bertha Coughlan’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 5, 2006. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Zoe Carthew.

In November 1922, Bertha Coughlan came to Melbourne from her remote and lonely farm in provincial Victoria. She had no mother, and her father and one remaining brother were not attentive. She had recently broken off her engagement and suffered the removal of all her teeth. Ostensibly, she came to the city to treat her chronic earache. But once there, she took the opportunity to remedy another, more scandalous, health issue. She separated from her negligent father and her disinterested family, and disappeared into obscurity.

For years, Nurse Hannah Mitchell had run a lucrative private abortion clinic from her large townhouse in Richmond. In 1922, she was sharing the house with her daughter, her sister, her nephew and her many patients. When her third ex-husband, Frank Bonfiglio, suddenly returned in November to renew his affections, Nurse Mitchell’s reputation and practice were thrown into jeopardy.

A dramatic procession of bloody and violent circumstances brought the very different worlds of Bertha Coughlan and Nurse Mitchell together – and to a tragic end.

List of Characters[1]

Hannah Mitchell, Nurse

Frank Bonfiglio, the third ex-husband of Nurse Mitchell

Bertha Coughlan, a young woman from Hinnomunjie in East Gippsland

Margaret Milward, Nurse Mitchell’s sister

Queenie Mitchell, Nurse’s daughter

Florence Spicer, friend of Margaret Milward

Ilma Clarice Walters, the nurse next door

John Coughlan, Bertha’s father

Rebecca Male, Bertha’s aunt

Thomas Cook, Coughlan family friend (suggested father of Bertha’s ‘trouble’)

Richard Thomas, Cook’s friend who knew ‘a respectable woman’

Lilian Mueller, the ‘respectable woman’

Sydney McGuffie, Detective

Frederick Piggott, Senior Detective

Edmund Ethell, Detective

Crawford H. Mollison, doctor at Melbourne City Morgue

Robert H. Cole, Coroner

Horace Solly, husband of one of Nurse Mitchell’s patients

Arthur Trood, Bertha’s dental surgeon

Harold Sharkey-Boyd, witness to a suspicious act

1 February 1923

At 11.10 pm Harold Sharkey-Boyd was crossing the Anderson Street Bridge in Richmond when he heard a man emerge from a parked car. He looked back to see the man struggle with a large, lumpy sack, which he unburdened over the side of the bridge. He heard a dull splash. Feigning apathy, if he had been caught looking, or ignorance, if he hadn’t, Sharkey-Boyd restored his attention to the street ahead. On the walk home, he stopped in at the police station.

At 9 o’clock the next morning, Detective Sydney McGuffie and Constable A Taylor from the Russell Street police department ‘commenced dragging operations’ close to the bridge. From a small boat off the bank they cast a broad net beneath the water. Their dredges of the stretch under Anderson Bridge at first seemed a waste of time: a motorcycle and some bicycle parts. McGuffie congratulated himself on the find: there was yesterday’s case of the missing bike solved.

Sharkey-Boyd had been thrilled to witness a suspicious act. In his statement to the police he dwelt gleefully on the brightness of the moonlight, the loom of the parked car, and the unshapely bulk of the mysterious sack. Senior Detective Frederick Piggott had been on duty with McGuffie the night before; they smirked at Sharkey-Boyd when he insisted he had witnessed a body-dump.

But as far-fetched as this was, it gave McGuffie and Taylor an excuse to keep dredging. At 2 pm, they ensnared a decaying black bran sack spewing weight-stones and tied with insulated wire. It had been in the water a lot longer than one night. This was not the bag that Sharkey-Boyd had seen being thrown over the bridge last night. McGuffie and Taylor gagged at the severe ‘stench’. They took it ashore. McGuffie cut it open. They found the sack contained another, a corn sack. Stuffed with muddied black fern leaves, the corn sack held the decomposing remains of a woman’s body. ‘The legs were bent up’, and between them was another bag. McGuffie looked closer, and read ‘Victorian Portland Cement Company, Cave Hill, Lilydale’ on the smaller bag. He hacked it open to find the woman’s skull, and a faded and slimy length of dark brown hair.

At the Melbourne City Morgue, Dr Crawford Mollison began a post-mortem, leaving McGuffie to identify the fern leaves and wash the hair. The hair was infested with pupa casings; evidence which, taken with the fern leaves, indicated that the depths of the Yarra had not been the dead woman’s only resting place. Dr Mollison discerned that the bones were those of a young woman with a distinguishing feature: she had no teeth.

PROV, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2001, Melbourne Supreme Court, Case number 151 of 15 March 1923.

Photograph by Akiko Kawasaki.

18 November 1922

Frank Bonfiglio ‘was staying with some Italian friends at the Palamara’s shop in Victoria Street’, Richmond. By an unhappy accident, Nurse Hannah Mitchell[2] had been passing by on her way to the Caulfield Cup at the very moment Bonfiglio was wandering out for the day. She stopped the taxi and skipped over, urging him to join her in an afternoon of revelry. She appealed to their mutual love of a flutter, to their shared personal history: he had the dubious honour of being Nurse’s third ex-husband. She won him over.

In the course of the afternoon they won £600. They didn’t talk about her little cottage industry: fixing women’s troubles. And they didn’t talk about the last time she had seen him, just before he got six months inside for (false) charges of cruelty against her. They certainly didn’t mention the dashing Mr Ridgway, her solicitor and ex-lover, who had been directly responsible for Bonfiglio’s time behind bars.[3] They didn’t even talk about little Margaret ‘Queenie’ Mitchell, his one-time step-daughter, who hated him and had never shrunk from saying so.

They had a splendid afternoon. When the taxi stopped at 4 Burnley Street in Richmond, Nurse Mitchell invited Bonfiglio inside to ‘sing a song’: Bonfiglio was a gifted tenor. He demurred, but said he would meet her later. At 9.30 pm he turned up on her doorstep, carefully shaven, wearing his best jacket. Nurse’s sister, Mrs Margaret Milward, let him in. Nurse Mitchell made a fleeting appearance, and told him to read the paper; she had ‘things’ to finish up. Bonfiglio made himself comfortable in the sitting room.

The house was full of people being quiet. Mrs Milward and her friend, Mrs Florence Spicer, were murmuring over coffee in the kitchen. Queenie Mitchell and Mrs Milward’s son Albert were upstairs amusing Albert’s little brother. The bedrooms downstairs contained various moaning or snoring girls, three and four to a bed, shamed and docile. Nurse Mitchell likely had another girl in the bedroom (strategically) nearest the bathroom at that moment. Bonfiglio shared the sitting room with a sickly looking man who introduced himself as Horace Solly. His wife was in a bedroom upstairs, awaiting a procedure; they had five little ones already, he told Bonfiglio, and himself ‘in a delicate state of health’ – well, Nurse Mitchell was their only hope!

But Bonfiglio was losing interest and patience. Twenty minutes later Nurse Mitchell came back transformed: brusque, cool, severe. She said, ‘I have a girl taken bad. Take your coat off and help carry her to the bathroom. Maggie will help you.’

In the third bedroom was a girl lying in a mess of blood. Her nightgown was soaked from the middle down and the sheets all around her were soggy and depressed. Bonfiglio coaxed her arms up loosely around his neck, and took her about the shoulders. Her lolling head was supported by his stomach. He staggered backwards, Nurse carrying her ankles, down the hall to the bathroom. She was not a small girl; in a swoon she was a dead weight. They laid her half on the table, with her head on a small cushion and her legs dangling over the side. Blood dripped on the lino.

‘Hold her,’ Nurse Mitchell barked. ‘Hold her head or she’ll fall down and kill herself. She’s very bad.’

PROV, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2001, Melbourne Supreme Court, Case number 151 of 15 March 1923.

Nurse Mitchell got two chairs and placed them side-by-side backwards at the end of the table. With Bonfiglio still holding the girl’s head, ‘Nurse Mitchell propped each foot on the backs of the chairs’. Mrs Milward hovered. Nurse went away and came back with her tools of the trade: a bowl of soapy water, a long, flat, silver instrument and a large syringe.[4] She put the bowl of water on the seat of one chair, and sat on the other, and bent to work: scraping, syringing, soaping.

Bonfiglio and Mrs Milward stood in the bathroom for forty-five minutes. While scraping, Nurse Mitchell said to Bertha, ‘Did I hurt you?’ ‘No,’ the girl panted. ‘You are a good girl,’ Nurse said firmly. She turned to Mrs Milward. ‘Call your son to get some brandy with a spoon.’[5]

Mrs Milward fed the brandy to the girl in small sips. Nurse Mitchell had ceased scraping and syringing. Now she put her hand up, inside the birth passage: ‘Cough, darling, and help me,’ she ordered. ‘The girl coughed three or four times’. ‘You are a good girl,’ she repeated. ‘Cough again.’ She removed her hand and rinsed it in the dish of soapy water, now lukewarm. The girl’s head sank back on the cushion. She was breathing fast and shallow, her long neck as exposed and prone as her legs.

Nurse Mitchell could hear the quiet glug of blood filling the girl’s womb.[6] She said to Bonfiglio, ‘I can’t do anything more for her; I have done my best; it is a serious case and it may be fatal. I am very tired. I cannot do any more; I think she is gone.’ She sluiced the coloured remains of the soapy water on the girl and said, ‘Carry her out of the bathroom again and into the bedroom.’

Mrs Milward, Bonfiglio and Nurse Mitchell made to lift Bertha from the table, but she began to haemorrhage. Soon she fainted. They waited for the flow to ease and carried her, still dripping, back to the bedroom. Nurse Mitchell said she was off to bed, and told Mrs Milward to keep up the sips of brandy. Bonfiglio followed her out of the room, intent on sleep himself, but Nurse Mitchell told him to ‘Go keep Maggie [Milward] company’. Bonfiglio objected.

Bonfiglio: Why didn’t you call a doctor?

Nurse: A doctor cannot do more than I did to her.

Bonfiglio: Why didn’t you have one before?

Nurse: Don’t worry; let me rest … I’m going to make a cup of coffee.

Nurse Mitchell walked off, leaving Bonfiglio and his conscience in the doorway of the bedroom.

Inside the room, Mrs Milward was leaning over the girl. She was rolling feverishly from one side of the bed to the other. Mrs Milward put a hand on her shoulder to calm her, and fed her another spoonful of brandy. ‘It is a shame to see the girl dying like this,’ she said.

Bonfiglio was still thinking about Nurse Mitchell. He said aloud to himself, ‘I am going to bed,’ and became aware that Mrs Milward had spoken. ‘Why don’t you go to bed?’ he asked. ‘I can’t leave the girl like this,’ she said. Bonfiglio sighed; he could not leave in good conscience.

The girl looked into Mrs Milward’s face and croaked, ‘I’m so cold. Could you rub my hands, please?’ Mrs Milward put the spoon aside and took her hands. The girl squeezed back weakly. She whispered, so that Mrs Milward could hardly hear over the gentle friction of their clasped hands and the bedclothes, ‘You are kind; you are so good to me.’ Mrs Milward tried to soothe her.

Mrs Milward: Never mind, dear … You will have a nice breakfast in the morning.

Girl: I won’t be alive in the morning. I’m dying.

Mrs Milward: No, you are not. Where is your boy?

Girl: I don’t know.

Mrs Milward: Don’t you know where he is?

Girl: Yes, I do, but I don’t want to say anything.

Mrs Milward: What religion are you, dear?

Girl: Church of England.

Mrs Milward: What is your name?

Girl: [fading fast] Cog …

Bonfiglio: She is gone.

Mrs Milward was still rubbing the girl’s hands, gently, gently. They were no warmer than when she began. ‘She is not; she can’t be gone,’ she said. Bonfiglio leaned close. ‘She is,’ he confirmed. He straightened up, and put a hand on Mrs Milward’s forearm, encouraging her to let go. The bedroom was cool and smelled of blood.

Mrs Milward went to the kitchen to brew a new pot of coffee. It was late. Mrs Spicer was in the kitchen. Everyone else was in bed. In an upstairs bedroom[7] Bonfiglio stood over Nurse Mitchell and shook her awake. She said, ‘I am tired, let me rest.’ Bonfiglio persisted this time: ‘Come and see her; you might do something for her.’ Nurse Mitchell yawned. ‘I suppose she is dead?’ Bonfiglio replied, ‘Just come and see her.’

In the bedroom, Mrs Milward gave Nurse Mitchell a coffee. Mrs Spicer had followed her from the kitchen. She peered at the girl from the doorway and said into the room, ‘You know what she said to me earlier? She said, “I wish I were a little bird and a cat come along and swallow me up.” Huh. Fancy a poor girl dying and none of her relations to know where she has gone.’[8]

‘It would be no good informing the relations,’ said Nurse. ‘It would be putting me away.’

Mrs Milward asked, ‘Is she really gone?’ Nurse deposited her coffee and drew the bloody sheet over the girl’s face. ‘Yes. Go to bed,’ she ordered them.

28 February 1923

The Coroner, Robert Cole, inquired into the identity of the woman in the bags and the nature of her death. The inquest took four days. Among those who testified to her identity were her dentist and her father. They addressed their statements to the Coroner’s legal representative, Scott Murphy.

In November 1920, dentist Arthur Trood had removed every last tooth in Bertha Coughlan’s head. She was a plain girl; porcelains could only improve her thin, long face. His bumbling account of the operation betrayed his profound personal disinterest in his patient’s identity and his professional interest in her cash payment. When Cole asked him to describe her face, he said he was ‘concerned more with her mouth and the work I was doing than with her features … I have seen hundreds of patients since then, probably thousands.’

John Coughlan was called to give evidence. He had reported his daughter missing in November.[9] After two and a half months, it was not a shock to know she was dead. He now gave her description to Cole as best he could. He couldn’t remember her birthday, but she was probably 27 or 28, he said, and he tried hard to remember how she looked. She was ‘inclined to be slight – very slight. Her hair was dark brown or black; I think you would call her eyes hazel; I would not swear; they were dark eyes … She had rather high cheekbones and was rather big in the features: she had strong features – long and strong.’ Here Mr Coughlan paused, searching for the right words for his daughter’s plainness, at once sturdy and sickly. He summed her up as best he could: ‘She had not a baby face.’ He began to tell the Coroner that Bertha had come to Melbourne to seek treatment for her chronic earache, but finished up telling the court about her chronic heartache.

1 November 1922

Bertha’s mother had been dead for almost a year. Her brother, James, had died years ago, just after the war. She wore his medal on her blouse as a brooch. Now there was only her father, her younger brother, Leslie, and herself at the little farm in Hinnomunjie, a gold-dredging community on the Mitta Mitta near Omeo. Bertha had broken off her engagement to Arthur Lemmon in July, and hadn’t seen him since. She was bored and lonely in remote Hinnomunjie. Lately her ear had been giving her trouble again and Dr McCardy in Omeo was no help. She was glad of the excuse to go to Melbourne.

Image courtesy of The Collector’s Marvellous Melbourne.

Bertha and her father came by train from Bairnsdale, arriving in the morning of 6 November. She had an appointment with Dr Ewing, an ear specialist, who prescribed an expensive relief. Feeling crabby from the train ride and alienated by the city, Mr Coughlan objected to the price at three different pharmacies across town. It was late afternoon by the time Bertha had her medicine; she could have cried. They adjourned to the Bull and Mouth Hotel in Bourke Street.[10]

Tuesday was Cup Day. Bertha left her father in the bar at the Bull and Mouth, and caught the train to Dandenong to visit her Aunt Rebecca and cousins. They invited her to extend her stay; they were sympathetic about her impossible father. She accepted tentatively. On Wednesday she returned to the city for another appointment with Dr Ewing. Her ear medicine of mercury and almond oil was proving effective, and its nasty smell provided Bertha with a fine excuse for her ritual morning vomit.[11] Her father hadn’t noticed, of course, but her Aunt had expressed concern.

Mr Coughlan saw her off at Flinders Street Station on Friday night. He complained that ‘she had about as much luggage as an ordinary man can carry’. That was the last he saw of her: her little black dress buttoned modestly up at the neck, a slate-coloured cloche pulled low over her anxious expression, and her brother’s medal pinned to her breast. Mr Coughlan went back to Warragul,[12] satisfied that his daughter was in someone else’s care for the summer.

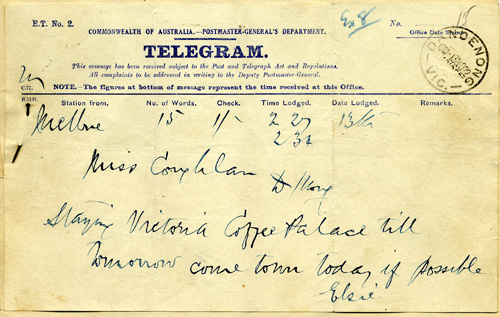

Bertha stayed with Aunt Rebecca for six days. As Aunt’s curiosity and concern increased, so did Bertha’s reservation and misery. On 13 November she packed some of her luggage and told Aunt Rebecca that she ‘was going to Camberwell to a Mrs Forbes and some people in Elwood’. The day after she left, a telegram arrived. It read: ‘Staying at Victoria Coffee Palace till tomorrow; come down today if possible, Elsie.’ Aunt Rebecca didn’t recall her neice mentioning this friend, but she kept it anyway, for when Bertha came back.

19 November 1923

It was Sunday. People drifted in and out of the house. Nurse Mitchell let her daughter, Queenie, check on the girls[13] while she visited Nurse Laura Gidley’s private hospital next door at 2 Burnley Street and spoke with Nurse Ilma Walters. A few days ago she had given Nurse Walters another girl who had taken bad; at least that one looked like she might improve. Nurse Walters was comfortingly matter-of-fact about patient mortality. Nurse Mitchell told her that Bertha had died because the placenta had been expelled before the foetus, and the foetus had got stuck high in the womb: placenta praevia.[14] Nurse Walters frowned when she said she hadn’t called a doctor. Nurse Mitchell suffered her righteousness for as long as it took to make sure her cast-off patient wasn’t dead by her own hand – two murders at the same time would look like she was losing her touch. She returned home and went to her room, coming out only to drink coffee and make telephone calls.

She caught Mrs Spicer alone in the kitchen, mid-afternoon; things needed to be done.

Mrs Milward: Never mind, dear … You will have a nice breakfast in the morning.

Nurse: Has Peg told you the news?

Mrs Spicer: No …?

Nurse: I have had trouble. The girl is dead.

Mrs Spicer: Why don’t you ring the police?

Nurse: It is too late now, the girl is stiff. I want you to go on an errand for me.

Mrs Spicer: Where do you want me to go?

Nurse: South Yarra. [she gives an address] You must tell a certain gentlemanto smudge his lights and meet me at Victoria Street Bridge. Ask him would he bring a carand take a body away – would he do that, and offer £300 or £400. The money does not make any difference; can you do that?

But Mrs Spicer’s mission was unsuccessful.

Nurse: How did you get on?

Mrs Spicer: He would do anything legitimate but he would not do anything crook. He said he had had a bad time with the police.

Nurse: I don’t know what to do; what would you do?

Mrs Spicer: [not tempted to comfort her] I don’t know. I’m going home.

By the time Bonfiglio returned in the evening, Nurse Mitchell had a new plan. She, Queenie, Mrs Milward and Bonfiglio all ate supper around the kitchen table. At 9.30 a taxi arrived;[15] Bonfiglio answered the door. ‘What have you got him for?’ he asked Nurse. She replied enigmatically, ‘Come for a drive in the fresh air.’

She directed the taxi to her son-in-law, Mr Torbey’s place in Faraday Street, and told Bonfiglio to wait in the cab; she would be back soon. Half an hour later she pulled up beside the cab in Mr Torbey’s Studebaker. Bonfiglio dismissed the taxi and took the wheel of the Studebaker. ‘I can drive any car,’ he boasted. They drove home. Nurse had been evasive all evening and now she was smug.

Nurse: Do you know what I got the car for?

Bonfiglio: No.

Nurse: To take the girl away.

Bonfiglio: Where are you going to take her?

Nurse: Healesville.

Bonfiglio: In this car? It won’t pull up the Spur!

Nurse: No. We are going to that place where we have been shooting.[16]

Bonfiglio: Why didn’t you tell me before?

Nurse: If you won’t help me, the people who have done this thing before will do it again; they have got a car.[17] [begins to cry] It’s your place to help me! You don’t want to see me hanged! [calms down] … Anyway, if anything comes to the worst I will confess it and say I am the only one to blame.

She had given him a lot to think about. He had known about her profession when they were married, but he had always chosen to remain ignorant of the particulars. To hear that this girl’s death was, while not a common event, nevertheless one of a number… And he couldn’t doubt that her promise to own all responsibility might mean exactly the opposite: he had served time in gaol for her convenience in their divorce. What, exactly, did she think ‘his place’ was?

14 November 1922

The ‘Elsie’ of the telegram was in fact Thomas Cook, who lived with his wife on a small farm near the Coughlans’ in Hinnomunjie. He had been in Albury for a race meeting (he had horses there) when he received a letter from Bertha in Dandenong. The letter asked him to come to Melbourne and, when there, to send her a telegram from ‘Elsie’.[18] She said she was in trouble. Would he help? Cook knew what Bertha’s ‘trouble’ was.[19]

PROV, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2001, Melbourne Supreme Court, Case number 151 of 15 March 1923.

Cook had a friend in Melbourne, Richard Thomas, an engine driver on the provincial trains. When Thomas was in Albury, Cook asked him for the name of ‘a respectable woman’ – specifically, a nurse. He also asked for some money. Thomas said he didn’t know any nurses, why would he? But he did know a respectable lady called Mrs Lilian Mueller. Cook said, ‘Will you give me a letter of introduction?’ Thomas fixed him up with a note, and the address of the Recreation Hotel in Spencer Street where Mrs Mueller worked. Cook left for Melbourne.

His telegram might have been too late, but at midday on 14 November he chanced to walk past the Bull and Mouth at the same time as Bertha was leaving. He thought she looked thicker around the middle, but it was probably just her dress, or his suspicion. Her thin, long face looked pallid and anguished. He took her back inside, into the bar. He said, ‘What is your trouble? Why did you write to me? Where’s Mr Lemmon [Bertha’s ex-fiancé]?’[20]

She said that Lemmon had sold out of his business outside Omeo, and she had not heard from him lately. ‘It does not concern you,’ she said sourly. He gave up trying to elicit her story, and cut to the chase. ‘I found a “respectable woman” for you,’ he said. ‘She will help you to find a nurse.’

‘Don’t do anything silly,’ he warned, to which she replied curtly, ‘It’s not what you think it is.’ Cook was doubtful, but the girl was alone and in trouble. He took pity on her. ‘If it’s for a good cause, then I can give you £10, but that is all. I don’t have any more.’ He told Bertha the address of the Recreation Hotel, then left for his lodgings at the Coffee Palace. Later that afternoon, he was strolling past the General Post Office in Bourke Street when he caught sight of Bertha, this time in the company of a stout, middle-aged woman of respectable, unfashionable dress. He nodded at Bertha and she acknowledged him; he kept walking.

Cook left for Albury the next day. He telephoned Mrs Mueller a couple of days later, to satisfy his conscience. Mrs Mueller assured him that ‘the girl is all right’. He was content not to know details; his duty was done. When he went home to Hinnomunjie in early December, he called on John Coughlan: ‘Have you heard from Bertha recently?’ Coughlan said he hadn’t. On 28 February 1923, Cook recalled to the Coroner: ‘She told me it was for a good cause, and I thought she was going to a hospital to be delivered.’

20 November 1922

Bonfiglio and Nurse Mitchell left the Studebaker around the side of the house and came into the kitchen. Mrs Spicer, Mrs Milward and Queenie were still up; it was past midnight. Nurse Mitchell helped herself to coffee and joined them at the table. She looked sternly at Mrs Milward and said, ‘Remember, you are my sister, and as a sister I expect you to stick to me in the trouble. Keep your mouth closed. Remember, don’t say anything about this to anyone. If you do, you will go to gaol.’ Bonfiglio had taken a seat at the end of the table, smiling grimly as she said this. ‘People that talk can always be silenced,’ Nurse Mitchell said.

Then she took a breath and continued in a gentler tone: ‘Peg, I want you to come for a motor ride.’[21]

Mrs Milward: Why do you want me to go?

Nurse: I want to go see Mrs Torbey. She’s sick.

Mrs Milward: I don’t want to go in the car with you! [to Mrs Spicer:] She wants me to go out with her to take the body! What would you do?

Mrs Spicer: I am not in a position to judge. You are her sister and I suppose she expects you to help her.

Nurse: Don’t be silly, Peg. You are coming.

Mrs Milward: [crying] I don’t want to go!

Nurse: You can do all the weeping when you come home; you will have more time then. We must go soon.

Mrs Milward: [mutinously] If I have to go, Queenie has to go.

Queenie: All right, Peg, I will go with you and Nurse and Mr Bonfiglio.

Nurse: Make yourself warm. [leaves the room]

The sheets around the corpse were stiff and conspicuous with old blood. Everything was awkward; the sheets wouldn’t wrap neatly.[22] Nurse Mitchell directed Bonfiglio to wrap it in fresh ones, and to fasten the shroud loosely with safety pins. They carried it to the car and placed it half on the floor between the front and back seats. ‘The head had to be bent’ to accommodate Nurse Mitchell and Mrs Milward in the back seat. Bonfiglio and Queenie were in the front. Bonfiglio drove up Whitehorse Road until they passed Melba’s cottage.[23] They took a right turn after the post office, and then another left, down a narrowing, desolate road. It was around 4 am; not as dark as before. They reached Coldstream and pulled through a gate bearing the sign ‘Yarra Bank’.

They were on a broad plateau above a wide, semi-cleared gully. Nurse Mitchell and Bonfiglio struggled to remove the slip-rails which would block their descent, while Queenie and Mrs Milward brought out the corpse. Queenie stayed at the car on lookout while the others lumbered down into the gully. At the bottom, they laid the body on the leafy ground and unwrapped the shroud. Nurse Mitchell grabbed handfuls of forest debris to cover it – large, dead, brown fern fronds and grey masses of gum leaves. Then she dragged a large plank of wood and laid it over the area to keep the weather away. She dusted off her hands and said, ‘She will be eaten by some animal in a few days, and it will not be known who she is if they find her.’ They climbed back to the car in silence. The horizon was beginning to glow; it was almost five.

They drove back to 4 Burnley Street. Mrs Spicer was in the kitchen having breakfast with Mr Solly. Nurse Mitchell went into the newly empty bedroom to remove all traces of the girl. ‘What have you done with the clothes?’ she asked Queenie. ‘I burnt them under the copper.’ ‘Good girl.’

Nurse and Queenie collected two small poison-bottles that Bertha had brought with her.[24] Before incinerating the girl’s effects, Queenie had removed a brooch made from a war medal, and a ring set with a small diamond. Now she showed these to her mother.

There was someone at the door. Nurse went and there found Mrs Mueller expecting to see ‘the young girl from the country’. Nurse Mitchell smiled at her.

‘She’s gone home,’ she lied. ‘She left yesterday. Didn’t she go to your place?’ Mrs Mueller was mystified. Nurse Mitchell said, ‘Well, she left here to go there.’ Mrs Mueller could only respond, ‘But she could not go to my place because there is nobody at my place that knows her, only me! I don’t even really know the girl. Her people are anxious about her; she hasn’t written to them.’[25] Nurse Mitchell continued friendly and ignorant: ‘She has probably gone to stay with friends. Of course, there are many girls here and they are encouraged to come and go as they please. I’ve been at the races lately.’[26] This was not an explanation, but Mrs Mueller was not, after all, responsible for the girl. She allowed Nurse Mitchell to distract her with talk of the races.

13 January 1923

Frank Bonfiglio was cooperating with the police, from the extreme discomfort of a hospital bed in St Vincent’s. Senior Detective Fred Piggott and Detective Ed Ethell were standing over his bed with notebooks and earnest expressions.

Det. Piggott: Hulloa, Bonfiglio! What has happened to you this time?

Bonfiglio: I have been shot.

Det. Piggott: Who shot you?

Bonfiglio: Nurse Mitchell.

Before Bonfiglio left for Western Australia, he and Nurse Mitchell had come to an understanding. They were going to start afresh. He was going to start a business. They were going to move interstate and forget about 4 Burnley Street and the dead girl. On the Saturday after they buried her, Nurse Mitchell had begged him to marry her ‘this afternoon!’ He promised he would, but only after he had re-established himself in Perth. She sulked, but let him go. He left his young son at her house while he was to be away – a gesture of his commitment. Their understanding included Nurse Mitchell’s promise of £40 up front and more to follow. From Perth, he sent her a telegram requesting £30. She wrote back, astonished and suspicious: why did he need £30 a mere fortnight after her generous gift? She had reason to be cautious; as long as she and Bonfiglio remained unmarried and at large he might be tempted to divulge the affair to police. The two of them had not shared the most peaceful of personal histories, she recalled. Soon after she had sent her reply her fears were realised. Bonfiglio now requested £500 in exchange for his silence about Bertha’s death. Nurse Mitchell took a risk; she did not send him any more money. Besides, there were many other parties apart from Bonfiglio to consider – stories to straighten, useful people to thank – and her racing fortunes could only fund so much silence.[27]

Without Nurse Mitchell’s extra contributions, Bonfiglio was unable to set up his business as a marble mason. Disheartened, he returned to Melbourne on 12 January, and called at 4 Burnley Street. He was unprepared for the nest of tensions he encountered. ‘Nurse opened the door, and was speechless to see him.’ He went upstairs to her bedroom and took off his coat. She came up behind him and finally said, ‘I got a shock to see you.’ She kissed him, less to renew her affections than to remind him of his loyalty. Then she said with bitterness, ‘It was nice letters you sent me; you can do what you like, you can tell a policeman if you want to. The body has been shifted and burnt under the copper.’ She was lying; she hadn’t burnt the girl.[28]

On his way out, Bonfiglio met Queenie. They had never liked one another. She hissed a warning, ‘If you do any harm to my mother I will shoot you, and I will shoot your son.’

When Bonfiglio came back that evening, Queenie answered the door. She directed him upstairs, hinting that her mother was emotional and ‘might do something to herself’. He climbed the stairs with trepidation. Nurse Mitchell was in her bed, and invited him to join her. He complied.

At 9.30 the next morning, Bonfiglio awoke; he shaved and dressed to go out. When he went downstairs, he noticed Nurse’s car out front.

Bonfiglio: What is the car for?

Nurse: We are going for a drive.

Bonfiglio: Where? I cannot go out. I have an appointment; where are you going?

Nurse: We are going for a drive in the country.

Bonfiglio: No, I have to meet a friend of mine at one o’clock.

Nurse Mitchell became suspicious of his ‘appointment’. She grabbed at his coat and pulled it off him. She rushed into an empty bedroom and thrust it in the closet. He was thumping behind her, irritated at her larks.

‘Where’s the coat?’ he snapped, at which she laughed affectedly and said, ‘I have a bad memory. As soon as I remember where I put it, I will give it to you!’ Then she became grave and dangerous. She stared at him. ‘I do not want you to have anything on me your whole life.’ Then she began to shoot…

Det. Piggott: Are you in pain?

Bonfiglio: Yes.

Det. Piggott: Have you suffered much?

Bonfiglio: A good deal.

Bonfiglio had every reason to feel vindictive. He told the detectives the truth: Nurse Mitchell had killed the girl, and hidden the body at Coldstream. ‘She missed me first,’ he said. ‘I rushed at her, and held her by the wrist.’ She fired another two shots. The fourth hit his arm. He fell heavily on the floor in front of the wardrobe, gasping, wounded. She shot him three more times. He was helpless at close range. He could only writhe and crawl on the carpet. One bullet hit his back. One hit high on his front, and another buried itself in the flesh beneath his waistcoat. Nurse said, ‘Frank, I am sorry but I have got to do it,’ and fired her last shot. Then she left, locking the door behind her.

Bonfiglio concentrated on breathing. He was probably dying. He slithered to the window and hauled himself up, leaving smears on the floor and the window ledge.[29] He walked wretchedly to Nurse Gidley’s next door. She patched him up, before calling an ambulance.

7 March 1923

Detectives Piggott and Ethell were subpoenaed to appear in the Coroner’s court. Bonfiglio’s shooting investigation had, thanks to his damning statement in St Vincent’s Hospital, brought about Bertha’s inquest. But though Bonfiglio had spoken specifically and at length about the mound of dead fronds which had formed Bertha’s first grave, this was not the detail which cracked the case.

Piggott’s statement to Robert Cole was laconic. In the last phase of the inquest, he told the Coroner and the court of witnesses, suspects and others:

I was told that the body had been removed twice. I was told that when it would be found, it would be found in a bag, and that the head would be in one portion of the bag and the body in the other, and that it was under water, and in that bag I would find ferns. I could not tell you from whom I found out this. I never tell you where my information comes from. I will go so far as to tell you that it is not one of the witnesses in this court, and it is someone who is not connected to the case in any way. I did not know that a body was under the Anderson Street Bridge. I suggest that the finding of the body … was a complete fluke.

Postscript

After the inquest, Nurse Mitchell, Bonfiglio and Mrs Milward were all arrested and released on bail while the police investigated Nurse Mitchell’s vast network of extortion and bribery. In April 1923 ‘Nurse’ Hannah Elizabeth Mitchell was tried for the ‘willful murder’ of Bertha Coughlan. She told Crown Prosecutor HCG Macindoe that in her professional opinion, Bertha had

asked me if she could stay for about a week as she did not want to go to her friends on account of her sickness as she was so ill and very often vomiting. From the signs and what she told me, I came to the conclusion that she was suffering a little bit from kidney trouble, and I advised her to see a doctor.

Nurse Mitchell was never prosecuted.

Endnotes

[1] Note on historical veracity: All of the dialogue, except where footnoted, is taken, verbatim, from witness testimonies at the Coroner’s inquest. Most of the descriptive details have been gleaned from the testimonies as well; exact descriptions are given in quotation marks. Some empathetic details have been fabricated, and these are acknowledged in the notes. Testimonies from the following witnesses were presented at the inquest between 28 February and 7 March 1923: Arthur Trood, John Coughlan, Leslie Coughlan, Rebecca Male, Samuel Ewing, Richard Thomas, Thomas Cook, Lilian Mueller, Frank Bonfiglio, Horace Solly, Margaret Milward, Florence Spicer, Ilma Clarice Walters, Sydney McGuffie, Frederick Piggott, Edmund Ethell. In addition, the testimonies of Frank Bonfiglio and Hannah Mitchell under cross-examination by Crown Prosecutor, HCG Macindoe, at the trial in April 1923 were relied upon in preparing this account. All case material is contained in PROV, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2001, Melbourne Supreme Court, Case number 151 of 15 March 1923. This includes the police report, Coroner’s inquest, Trial transcript: His Majesty vs. Hannah Elizabeth Mitchell, Prosecutor’s notes, Police evidence including dried fern-leaves, transcripts of telegrams and letters, transcripts of witness statements, and map of the accused’s house.

[2] Nurse Hannah Elizabeth Mitchell was called simply ‘Nurse’ by her daughter and sister, and by her ex-husband Bonfiglio. She was a nurse by vocation, and her home was her workplace. Her daughter Queenie worked under her supervision as her apprentice in the house. Bonfiglio refers to her as ‘Nurse’ and ‘Nurse Mitchell’ in the Coroner’s inquest and in the trial transcripts.

[3] The love triangle: Bonfiglio said later that Nurse and Ridgway had colluded to get him out of the picture. He maintained they had trumped up the charges of cruelty against him.

[4] The first (and usually the only) procedure upon unwanted pregnancies was performed with a catheter. This long, sharp instrument was inserted into the vagina and ‘poked’ into the womb to disturb the foetus, which would detach and be expelled from the womb within a matter of days. Nurse Mitchell’s house was ‘reputable’, insofar as she allowed the patient to remain under her supervision until the miscarriage occurred. Other ‘backyard’ abortionists sent the patient home to deal with it herself. If the miscarriage was not clean – that is, if there appeared to be excessive bleeding (as was the case with Bertha) or if the foetus and other womb materials had not been successfully expelled – a second procedure was performed. This was called curetting, and involved simultaneously scraping and rinsing the opening of the womb and the birth canal of any remaining matter. The instruments used were a long silver syringe (the curette) and a speculum, to hold the area open and unobstructed. This was a last resort, usually preceded and followed by heavy bleeding. If detached matter remained in the womb or birth canal, the danger was that it might become septic and spread infection which would be fatal to the patient.

[5] This conversation has been fabricated from the inquest accounts of Bonfiglio and Margaret Milward. Nurse Mitchell did ask this of Milward.

[6] Later Nurse Mitchell told her neighbour Nurse Ilma Walters that while she was ‘working on’ Bertha she could ‘hear her filling up’ with blood. Nurse Walter’s statement was quoted in the Coroner’s inquest.

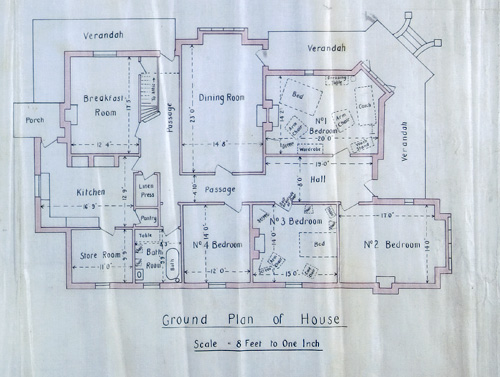

[7] It is unclear from the testimonies and the floor plan sketch whether Nurse’s bedroom was on the upper or ground level. Here, Bonfiglio indicates that it was upstairs, but later, when he was shot, he said he climbed out the window (quite a feat from the upper level). There may have been some kind of landing.

[8] Mrs Spicer recalls Bertha’s cat-and-bird speech in her testimony, but it is not known whether she mentioned this to the other people in the house.

[9] This detail may be inferred from the evidence, but is not recorded.

[10] John Coughlan said that they stayed at the Bull and Mouth in Elizabeth Street, not Bourke, but he was not familiar with Melbourne.

[11] While this detail is not recorded, the testimonies reveal that Bertha worried about her morning sickness becoming conspicuous to her Aunt, and Dr Ewing’s prescriptions of mercury and almond oil were nasty and, quite possibly, poisonous.

[12] The rural city of Warragul was a township in the 1920s, south-east of Dandenong on the train line back to Gippsland.

[13] I have added this detail: Queenie was Nurse

Mitchell’s trainee, she called her mother ‘Nurse’ and she attended to patients.

[14] It is not clear whether placenta praevia killed Bertha or not. It appears from the inquest and trial that Mrs Milward and Queenie saw the expelled foetus among the bed sheets, and Nurse was known to have said, ‘Thank god, I have got the foetus. I have saved the girl.’ It is likely Nurse Mitchell told Nurse Walters that the foetus was not expelled, so as to have a blameless explanation for Bertha’s death; Nurse Walters was called upon during the inquest and trial as an expert witness, to give a detailed medical opinion.

[15] Bonfiglio says 9.30 pm at the inquest and 10.30 pm at the trial.

[16] Nurse Mitchell refers to an activity the couple once enjoyed.

[17] Nurse Mitchell refers to the other times she has had to dispose of a corpse, and the help she bribed.

[18] Thomas Cook was later arrested for sending a telegram under a pseudonym.

[19] This is alluded to in the inquest testimony of Emily Elizabeth Tucker, who ran a boarding house to which Bertha applied for accommodation the day before she was admitted to Nurse Mitchell’s: ‘She [Nurse] told me that a young fellow in the country was responsible for the trouble. She said that the girl had carried on with a married man.’

[20] This conversation has been reconstructed from Cook’s account of his meeting with Bertha.

[21] This was never a whole scene; Nurse and the others were buzzing around the house, in and out of rooms, speaking with one another separately, and not always in the others’ company.

[22] Bonfiglio’s and Milward’s testimonies referred to the body being wrapped in a blanket and a sheet, it is not clear which. It is also not clear who wrapped the body.

[23] Coombe Cottage, the residence of Dame Nellie Melba, Melbourne’s celebrated opera singer. It is mentioned several times throughout the inquest and trial, as a local landmark.

[24] Bertha’s nasty ear medicine, used by Dr Ewing and the Coroner to identify her at the inquest.

[25] The latter part of the speech is a creative addition: I have reconstructed Mrs Mueller’s speech to Nurse from her account at the inquest.

[26] It is unclear exactly what Nurse said to Mrs Mueller to distract her from Bertha’s welfare. Bonfiglio testified that after Nurse lied to Mueller they stood chatting about the horse races for a considerable time.

[27] The various testimonies from marginal characters indicate that Nurse Mitchell embarked upon an orgy of extortion and favour-granting, using her regular, large race winnings. In December she had three men remove the body from Coldstream. They took it to a well and reported back. Mrs Milward recalled that the men wanted to move it again, and that Nurse Mitchell approved.

[28] Nurse Mitchell told Bonfiglio that she had removed the body from the gully in Coldstream and burnt it. Bonfiglio indicated in his inquest account that he did not believe this (possibly because she had never burnt any other dead patients). He thought it reasonable to believe she had moved it. When he gave evidence to the detectives, he said he suspected that the fern leaves at Coldstream would prove the truth of the matter. It is unclear why Nurse’s hired help relocated Bertha’s corpse from Coldstream back to Richmond for the hapless Sharkey-Boyd to detect; perhaps they thought that another body in Richmond’s Yarra had better chance of decaying unnoticed than it would in the secluded environs of Coldstream.

[29] This detail is my own invention.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples