Last updated:

'Criminals, Prostitutes, Vagrants and Drunkards: 1920s Carlton', Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 5, 2006.

ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jessica Stagnitti.

In the 1920s the Melbourne suburb of Carlton was a squalid slum, a home to, amongst others, criminals, prostitutes, vagrants and drunkards. This essay locates three individuals whose lives were trapped within these depressing conditions. A mystery slowly unfolds in a boarding-house in Lygon Street… An alleged prostitute, Kathleen Price, is murdered by her partner, Charles Johnson, a cocaine addict… Kathleen’s daughter, Doris Price, and other boarding-house residents look on helplessly… In preparing this piece, the author has used the original records creatively to develop empathy with the characters and to highlight the drama of these extraordinary events.

List of Characters

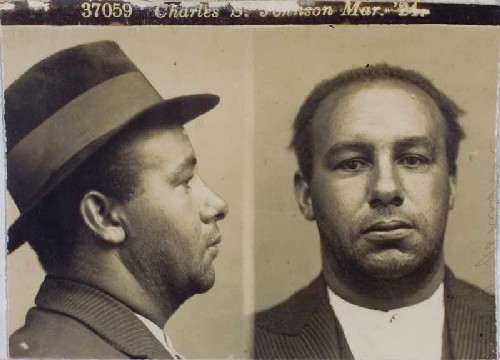

Charles Johnson, the murderer in question

Kathleen Price, Charles’s victim

Doris Price, Kathleen’s daughter

Senior Constable Murray, who apprehended Charles

Senior Constable Crawford, who apprehended Charles

Clara Aumont, boarding-house keeper

Stanley Stanton, boarding-house tenant who occupied the room opposite Kathleen’s

Henry Gaw, fought alongside Charles in World War 1

John Andrew, long-term friend of Charles; also fought alongside Charles in World War 1

Mr Justice Mann, Judge

Maisie M’Cool, companion of Kathleen

Tessie Connelly, companion of Kathleen

‘In night attire and with her bare feet bleeding from the cuts caused by the rough roads, Doris Price, aged nine years, ran into the Carlton police station, Drummond Street, shortly after 2 o’clock yesterday morning and cried, “A man has mother by the hair and is cutting her neck with a table knife.” The little girl brought the first news of a horrible tragedy.’

(Argus, 3 December 1923)

* * *

On 3 December 1923, Charles Johnson awoke with a start. Sounds of boisterous drunk men and cackling women pervaded. He scanned the unfamiliar room. Where was he? How did he get here?

He lay on a thin mattress in a bare room. He had no memory of the events leading up to this point. He looked down at his hands: blood-stained. He looked around, bewildered. His heart raced with anxiety at the possibilities.

A stern-looking policeman entered the cell of the City Watch House and informed Charles of his actions the night before. Charles expressed horror as each word assaulted his ears. His howls echoed through the outside corridors.[1]

* * *

Henry Gaw and Charles Johnson were fellow combatants in World War 1. Henry had witnessed Charles’s volatile nature. He testified at the Supreme Court in 1924:

When I said he was erratic I mean on one occasion when I was with him in a canteen in Sutton Veney in England he had this stuff. I did not know what it was at the time. He had one drink with me and finished up punching three of us. We got hold of him and held him down on the floor of the canteen. He calmed down in about half an hour’s time and I asked him what he done that for. He said he did not remember. I meant what did he punch us for – his own mates. He said ‘I don’t remember.’[2]

* * *

Who was Charles Johnson? Below are the findings of Senior Constable Murray written in 1924.

I have to report that Charles Sydney Johnson was born in Brunswick 29 years ago. His father who was a full-blooded American Negro, died 20 years ago, and his mother who was a white woman, died 16 years ago. Very little is known of Johnson’s early life up till he was 16 years of age, when he was fined 40/- or 14 days imprisonment at Brunswick for playing two-up, but from that date right up to his arrest on this charge of murder he was unfavorably known by the police.

At Brunswick on the 2/9/14 he was fined 10/- for obscene language, and at the same court on 24/3/15, was fined £5 or 2 months imprisonment for unlawful assault. On the 5/4/15 he was arrested in company with a man named George Watson on a charge of murder, the victim being a man named James Gregory, who was killed by being struck on the head with a bottle, on that occasion, Johnson gave the name of Charles Wilson. Both accused appeared before the City Court and Watson was discharged, but Johnson was committed for trial and on his presentment at the criminal court was found not guilty. From that time up to the date of his enlistment in the A.I.F, he was employed at the Hoffman Brick works, Brunswick. He enlisted on the 8/7/15 and returned to Australia on 6/10/19. His military record is in the possession of the Crown Solicitor. Since his return he has been following the occupation of a Hawker, but as far as I can ascertain, he lived principally on the earnings of the deceased woman, Kathleen Elizabeth Price, who was a prostitute, and with whom he was living. He is a man of drunken habits, and when in drink, very violent and quarrelsome. He was also the companion of convicted thieves and prostitutes and frequented the slum area of the city.[3]

Senior Constable Murray had read Charles’s military record. It revealed numerous hospital stays for the treatment of venereal disease. While away at war, Charles also suffered from mumps, septic knees and influenza. In 1916 he was wounded in action in France and transferred to England for the treatment of his wounded left leg.[4]

Many offences are listed on Charles’s military record: for using insulting and insubordinate language, for being drunk, for numerous absences without leave, for escaping custody, and for assaulting another soldier. Charles served time for these offences in military prison in France and England.

* * *

At the top of the stairs, Senior Constables Murray and Crawford saw that the walls were sprayed with blood.[5] The door of the bedroom was open. A double bed stood sideways between two windows. Before it, on the floor, lying face downwards in a pool of blood, was the fully dressed body of a woman.[6] The woman was Kathleen Price. Her light-blue knitted silk jumper, navy-blue skirt, white shoes, stockings and hat were soaked with blood.[7] Murray and Crawford found that Kathleen’s head was nearly severed from her body.[8] Cuts, scratches and bruises were found all over her. Her left thumb had been almost severed at its joint. Her face was cut, scratched and bruised. Her lower lip was swollen, her eyelids were blackened.[9] A curved table knife was found lying near her right hand. There was evidence of a fierce struggle. In the corner of the room a blood-stained bread knife was found. The heel of Kathleen’s left shoe had been torn off, and her false teeth were found in a far corner of the room.[10]

Kathleen Price, aged 30, was a married woman who had been separated from her husband for five years.[11] She and Charles Johnson had been living together as man and wife in a boarding-house at 230 Lygon Street. They shared the front bedroom on the second floor of the boarding-house. Kathleen’s nine-year-old daughter, Doris, occupied a separate room, two or three steps away from her mother’s.[12]

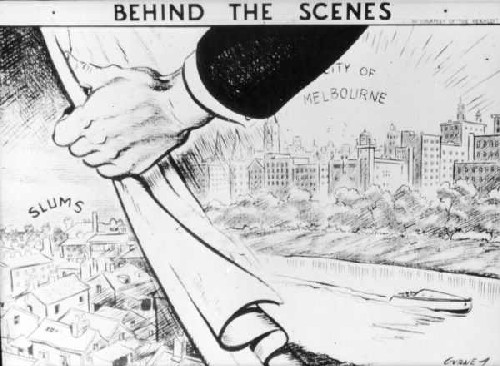

Today Lygon Street, Carlton is a colourful array of Italian restaurants, a trendy environment occupied by the middle class. But not so long ago Carlton was very much a working-class suburb, home to, amongst others, prostitutes, vagrants, criminals and drunkards. Various writers in Peter Yule’s Carlton: a history describe how Carlton’s renaissance through the late 1950s to the late 1970s transformed this ‘squalid slum’ into the vibrant and fashionable suburb we know today.[13] Carlton in the late nineteenth century

was a ‘breeding ground of crime’.[14] Its inhabitants were frequently depicted by the police and government as social outcasts, unwashed and dirty. The poor were stigmatised ‘with stereotypes that linked poverty with depravity’.[15] Anderson, Coney and Nelson in Carlton: a history draw on the work of Marie Sturt in Among the Terraces to explain how:

[t]he economic depression of the 1890s reinforced Carlton’s reputation as a place rife with crime. Slum growth accelerated with the onset of the Depression and was particularly apparent in Carlton’s south, where many larger houses were converted into boarding-houses after their previous owners had vacated.[16]

Many people lived in cheap, often dilapidated boarding-houses in the 1920s. In The outcasts of Melbourne, Shurlee Swain describes the endemic poverty of places like these.[17] Already in 1854 the Argus had noted that boarding-houses were ‘overcrowded and filthy to a degree’; that they were ‘scenes of extortion, drunkenness, riot and robbery, if not murder’ and, in many cases, places where ‘drugs were kept’.[18] Poverty and misery motivated much criminal behaviour, and in turn local criminal acts only worsened the depressed conditions. Not much had changed by the 1920s. Carlton still housed some of the poorest people in Victoria.[19]

Charles, Kathleen and Doris lived in this environment. Clara Aumont, their boarding-house keeper, had commented incidentally to Constables Murray and Crawford that these three had been the ‘happiest family she had ever seen’.[20] Doris called Charles ‘father’. Clara did not discover until the day of Kathleen’s murder that Charles and Kathleen were not married.[21] For the four weeks that they had been living in the boarding-house,[22] no one had heard the slightest murmur of an argument between them.[23]

La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

What happened? About 9.00 pm on Saturday night, 1 December 1923, Doris crawled into her mother’s double bed. She was not asleep, but looking through her school books.[24] Her mother was not home. Kathleen was working as a waitress at a café in the city, and did not finish until late at night.[25] Charles Johnson would usually meet her and bring her home. On this occasion Kathleen returned home with Charles at about 1.45 am.[26] Kathleen quietly entered the bedroom, kissed Doris and told her to go to her own room. ‘Johnson then was drunk. He was in a bad temper and in every bad temper I went to my own room’, Doris later told the Coroner.[27] Doris left her mother’s room. She entered the little passage connecting their two rooms, and three steps later was in her own bedroom. She was just drifting off to sleep when she was startled by her mother’s shrill screams.[28] She jumped out of bed and ran to her mother’s room.

Charles had her mother by the hair, about to draw a table knife across her throat. Doris pleaded, ‘Daddy, don’t!’[29] Charles then pulled the knife back, hit Doris across the face, and drew the knife across Kathleen’s throat. Causing only a superficial wound, he growled ‘This knife is not sharp enough!’[30] He threw it under the sofa, which stood parallel to the double bed, against the wall.[31]

Doris watched in horror as Charles pushed her mother viciously to the ground. He then went to the drawer and retrieved a sharp table knife. He whispered mockingly to Kathleen, ‘I will get the bitch’, referring to Doris. Doris sprinted downstairs screaming. She was met on the way by Clara Aumont, who was running up the stairs to Kathleen’s defence. Doris anxiously followed Clara back to her mother’s room. Her mother was slumped on a wooden-framed chair.[32]

Kathleen regained some strength and rolled under the bed. Charles pulled her out by the leg. He twisted it, nearly breaking it. Doris and Clara looked on helplessly. Clara, in a voice trembling with fright, instructed Doris to get Stanley Stanton, the man who occupied the room opposite her mother’s.

Stanley came running. Doris followed. Stanley implored Charles to stop. Charles ignored him. He picked Kathleen up off the ground and threw her onto the side of the bed. She got up and tried to get away from him. Charles said mockingly, ‘You will get away will you?’ He kicked her in the face and then on the head. She lay bleeding on the ground. He knelt, and while holding her down, sliced her throat from ear to ear. He then rolled her over onto her face.

Stanley, Clara and Doris ran downstairs, fleeing to the front downstairs bedroom occupied by an invalid. They stood nervously as they heard footsteps. Charles entered the room. The invalid man said, ‘You are cruel to do that to the woman.’ Charles threw a punch at him. With urgency in her voice, Clara gasped, ‘Quick, Doris, go and get the police, quick!’ Doris ran out into Elgin Street. In a nightdress she stood in the dark street in utter terror and cried. A man heard her crying and came out of a shop. The man took her to the police.

Clara stayed in the front downstairs bedroom with the invalid man after Doris had run for the police. While still in the room, Charles showed Clara his hands, all covered with blood. Splashes of blood were all over his face and clothes. ‘He was like a lunatic and was singing out and was mad. He was not sober, he was drunk, he did not seem to know what he was doing’, Clara later told the Coroner.[33] Clara accusingly asked Charles, ‘What have you done?’[34]

Charles replied, ‘She is as dead as Julius Caesar. I loved that woman; I will go to the gallows for her.’ Witnesses later reported: ‘he was throwing his hands in the air … his eyes were staring out of his head … he looked as if he was a madman.’[35]

Senior Constables Murray and Crawford were in the Carlton Police Station when Doris arrived.[36] Both were tall men, Murray with light grey eyes, red hair and a pale complexion, Crawford with light blue eyes, fair hair and a fair complexion. Doris’s dishevelled appearance raised alarm.[37] The two men ran to the house, Murray carrying little Doris, who was nearly hysterical.[38] The door of the house was open. Charles was standing on the doorstep. His light grey suit was soaked with blood.[39] Blood dripped from his hands.[40] Clara was seated in the hall, crying bitterly.[41]

Constable Murray composed himself, and enquired, ‘What is the matter here Johnson?’

Unwilling to cooperate, Charles replied, ‘Nothing.’

Constable Murray said, ‘We will go upstairs and see.’

Charles replied, ‘Yes come upstairs and see.’

They made their way up the narrow staircase to the front bedroom. The sight of Kathleen shocked the constables. Murray asked Charles, ‘Did you do this?’ He replied, ‘There she is, she is dead alright, I will say nothing.’

Murray pulled out his handcuffs and prepared to place them on Charles. He had been quite calm up until then, but now began to struggle violently. Murray fastened the handcuffs on his left hand, but Charles struck out with his right. Constable Crawford was knocked down the narrow staircase. After some effort, the constables finally managed to restrain their charge. He was then taken to the City Watch House.

PROV, VA 667 Office of the Victorian Government Solicitor, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924.

On 16 February 1924 the Age reported:

In the opening case for the defense Mr. Brennan said there was no doubt that [the] accused caused the woman’s death, but there was a mystery overhanging it. Although not man and wife, the two people were living together apparently in the most complete harmony and love. Evidence would be called to show that the accused was a cocaine victim. Cocaine was the most powerful and attractive of all drugs, and a victim could not free himself of its influence. Johnson had persistently taken that drug. A man under its influence was without memory, will or the power of forming an intention. He was not merely a lunatic, but was worse in that he had no understanding of what he was doing.

Charles had acquired the habit of sniffing cocaine while serving in the army during the war. John Andrew, who had known Charles all of his life, had spent six months with him overseas and was with him in the camp at Sutton Veney, in Wiltshire. John remarked at Charles’s trial that most soldiers at war took cocaine ‘to make them a bit game to go into the trenches’.[42]

John testified that after he had been sniffing cocaine, Charles ‘used to go mad and wanted to fight everybody’. In London at the time of the war, Charles had even hit John with an entrenching tool on one occasion, after he had been sniffing cocaine. ‘He had no reason whatsoever for striking me. He was my best friend. He said it was the dope and he could not help it, he did not know what he was doing. He was otherwise absolutely friendly with the men in the camp, when he was quiet.’

Charles’s trial lasted only one day. He pleaded not guilty to the charge that on 2 December 1923 he murdered Kathleen Price. There was no controversy over the fact that Charles had caused the death of Kathleen; what was controversial was whether or not Charles was capable of forming the intention to kill her. For the jury to find Charles not guilty, Mr Justice Mann explained that they would have to find Charles insane. If they came to the conclusion that Charles was not insane, but that his mind was so affected by drugs or alcohol that he was incapable of forming the intention to kill Kathleen, or inflict grievous bodily harm, they should bring on a verdict of manslaughter. However, if they were to conclude that Charles had committed the fatal act with the intention of killing Kathleen, or of inflicting grievous bodily harm, their verdict should be murder.[43]

On 15 February 1924 Charles was found guilty of murder with a strong recommendation for mercy. When Mr Justice Mann asked Charles if there was any reason why the sentence of death should not be brought upon him, he said ‘No’. Charles was sentenced to death; to be hanged by the neck until dead.

The Age newspaper reported that he showed no emotion when his sentence was pronounced.[44]

This sentence was later commuted to imprisonment for the term of his natural life without the benefit of any regulations relating to remission of sentence.[45] Charles served 11 years at Pentridge and four years at Geelong Gaol, where he died on 1 July 1939.[46]

And what of Kathleen? The records always seem to tell us so much more about perpetrators, and little about the victims. Who was Kathleen and what might her life have been like? Neither court proceedings, nor the articles in the Age and Argus newspapers ever made mention of Senior Constable Murray’s belief that Kathleen Price was a prostitute. These newspapers reported only that she was a waitress in a café in the city. Even Murray, in his report dated 2 December 1923, stated that Kathleen was believed to be a waitress.[47] His findings, including his statement that Kathleen was a prostitute, were compiled after the sentencing of Charles Johnson in 1924. Perhaps by then Murray had stumbled across new information implicating Kathleen as a prostitute.

Writers in Carlton: a history draw on Chris McConville’s work in Outcast Melbourne to claim that ‘in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century many brothels operated in Carlton, particularly in Lygon and Bouverie Streets’, and were operated by both men and women.[48] McConville has described how prostitution in the 1920s took place in city hotels, slum houses, suburban mansions and the dilapidated terraces of inner suburbs. These locales sustained two distinct lifestyles:

Secure, but with little freedom, the ‘dressed’ girls worked in exclusive brothels. The Madame kept their earnings, dressed [her] girls in expensive outfits and demanded that they bring back only ‘respectable’ clients. At the other extreme, old or diseased prostitutes, ‘filthy creatures having barely sufficient clothing to cover their nakedness’, hung about city lanes or camped on vacant blocks ‘where they … adjourn for immoral purposes when they happen to wheedle a drunken man into their meshes’.[49]

Successful prostitution relied on police reaction. Police rarely questioned the ‘dressed’ girls or their wealthy patrons, but hounded poorer women wherever they went. McConville writes: ‘On the move constantly between slum and cheap boarding-house, it was upon these unfortunate few that the full weight of moral sanction was pressed.’[50] Being identified through arrest made the situation of these women even more precarious. They were then forced to follow a path leading towards legitimate work or respectable marriage.

PROV, VA 667 Office of the Victorian Government Solicitor, VPRS 30/P, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924.

Perhaps Kathleen became caught in this web. The Argus reported on 4 December 1923 that:

Plain-clothes Constables Murphy and Snowden visited a house in Little Lonsdale Street, where they recovered the handbag of the dead woman. It is stated that Mrs. Price visited the house on Saturday, and obtained supplies of cocaine in the form of ‘snow’. She is believed to have returned home under the influence of the drug. Two women were arrested yesterday by the constables in the house in Little Lonsdale Street on charges of vagrancy.

The two women, Maisie M’Cool, 27, and Tessie Connelly, alias Julien Beckman, 27, were alleged companions of Kathleen Price.[51]

McConville describes how, under the law, individuals with insufficient means of support could be arrested

for vagrancy – for being ‘idle and disorderly’.[52] ‘Many of those apprehended [for vagrancy] were prostitutes, thieves, drunkards and gamblers – collectively regarded as social outcasts’. Also arrested on the charge of vagrancy were members of the working class, the poorest of whom were often unable to afford housing. Many women apprehended for vagrancy were ‘considered undeserving of charity’. As McConville describes it:

According to the hierarchy of benevolence, single mothers, alcoholics and women who did not adhere to the rigid rules of respectability were not worthy of assistance. It was thus easy for such women to become destitute.

The story of Charles, Kathleen and Doris reveals a desperate world, now forgotten. The events that changed their lives forever are true, uncovered from 83-year-old files held at Public Record Office Victoria, the Victoria Police Museum and in newspaper articles of the day. Next time you walk down fashionable Lygon Street, visit number 230, now a bustling restaurant, and remember that not so long ago the street in which you stand was once part of a slum, shaping the blighted lives of people like Charles and Kathleen and little Doris.

Endnotes

[1] Narrative reconstructed from report in the Age, 16 February 1924.

[2] PROV, VA 2825 Attorney-General’s Department, VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, Transcript of trial, Supreme Court Melbourne, 15 February 1924, testimony of Henry Gaw.

[3] ibid., testimony of Senior Constable Murray.

[4] PROV, VA 667 Office of the Victorian Government Solicitor, VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, Coroner’s Inquest, Charles Johnson’s military record.

[5] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[6] Age, 3 December 1923.

[7] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, Coroner’s Inquest, testimony of Senior Constable Murray and Transcript of trial, testimony of John Brett.

[8] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[9] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, Transcript of trial, testimony of John Brett.

[10] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[11] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, Coroner’s Inquest, testimony of John Sylvester Price.

[12] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, Transcript of trial, testimony of Doris Price.

[13] A Mayne & K Zygmuntowicz, ‘Postwar Carlton’, in P Yule (ed.), Carlton: a history, Melbourne University Press, 2004, p. 37.

[14] F Anderson, C Coney & E Nelson, ‘Crime’, in ibid., p. 431.

[15] loc. cit.

[16] Sturt, cited in ibid., p. 431.

[17] S Swain, ‘The poor people of Melbourne’, in G Davison, D Dunstan & C McConville (eds), The outcasts of Melbourne: essays in social history, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985, p. 103.

[18] Cited in G Davison, ‘Introduction’, in ibid., p. 8.

[19] Anderson, Coney & Nelson, ‘Crime’, p. 432.

[20] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[21] loc. cit.

[22] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, Transcript of trial, testimony of Clara Aumont.

[23] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[24] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, Transcript of trial, testimony of Doris Price.

[25] loc. cit.

[26] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, testimony of Senior Constable Murray.

[27] ibid., testimony of Doris Price.

[28] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, Transcript of trial, testimony of Doris Price.

[29] loc. cit.

[30] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, testimony of Doris Price.

[31] Photo of crime scene in ibid.

[32] ibid., testimony of Doris Price. The next section of the narrative is also drawn from this testimony.

[33] ibid., testimony of Clara Aumont.

[34] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson, testimony of Clara Aumont.

[35] loc. cit.

[36] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[37] Victoria Police Museum, Record of Conduct and Service, John Martin Murray and Frederick William Crawford.

[38] Argus, 3 December 1923.

[39] loc. cit.

[40] Age, 3 December 1923.

[41] Argus, 3 December 1923. The next section of the narrative is also drawn from this source.

[42] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson. testimony of John Andrew. The following two quotations are also taken from this source.

[43] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson.

[44] Age, 16 February 1924.

[45] VPRS 264/P/1, Unit 30, Item Charles S. Johnson.

[46] PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 515/P/0, Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 73, Folio 342, Chas Sydney Johnson, registration no. 37059.

[47] VPRS 30/P/0, Unit 2029, Melbourne Supreme Court, case number 5 of 15 February 1924, testimony of Senior Constable Murray.

[48] C McConville, Outcast Melbourne: social deviance in the city, 1880-1914, Melbourne, 1974, cited in Anderson, Coney & Nelson, ‘Crime’, p. 436.

[49] C McConville (citing a Mrs Nicholson), ‘From “criminal class” to “underworld”‘, in Davison, Dunstan & McConville, The outcasts of Melbourne, p. 79.

[50] ibid., p. 80.

[51] Age, 4 December 1923.

[52] McConville, cited in Anderson, Coney & Nelson, ‘Crime’, p. 435. Further quotations are from this source.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples