Author: Natasha Cantwell

Communications & Public Programming Officer

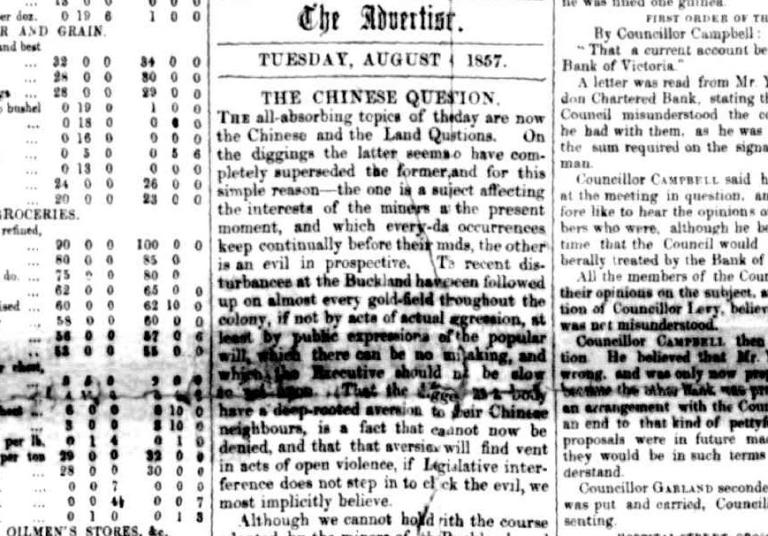

Robyn Ansell began researching her family history in the early 1990s, intrigued by small snippets of information her mother knew about their Irish/Chinese background, and almost thirty years later she is still enjoying the thrill of the chase and the joy of discovery that research brings. One publication in particular, the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser, has been a constant source of inspiration, because as Robyn explains, documents like rate books and marriage certificates can give us facts but “it’s the newspapers that put the flesh on the bones.” Now, with the support of a Public Record Office Victoria Local History Grant, early issues (1857 – 1867) of this local paper have been digitised and are easily accessible to the general public through the popular National Library of Australia website Trove.

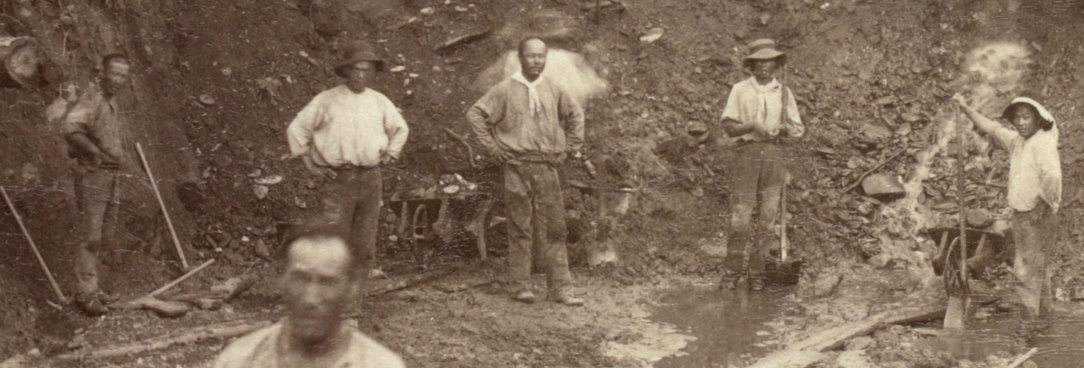

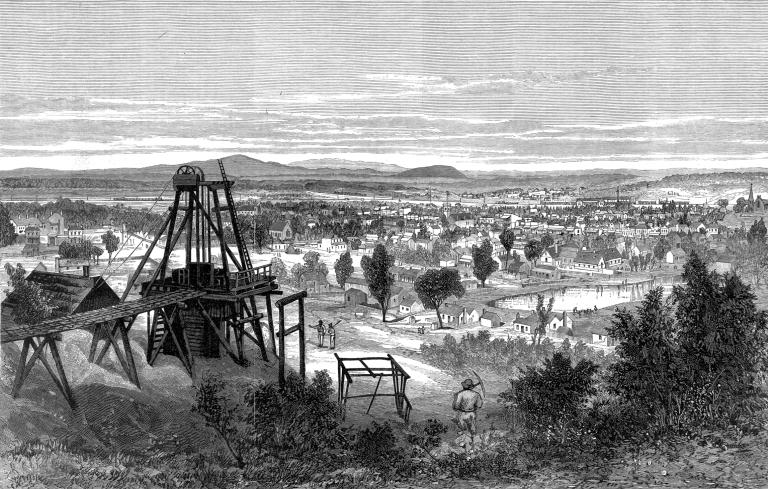

As a founding member of the Chinese Australian Family Historians of Victoria, Robyn understands how much the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser is an important resource for researching Victoria’s early Chinese immigrants. Gold was first discovered in Maryborough in 1854, and by the following year, the district had attracted at least 4600 Chinese settlers. Other newspapers from the goldmining era, including Ballarat and Bendigo were already up on Trove, but until now, accessing the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser’s 1857 to 1867 issues required a trip to the Maryborough Midlands Historical Society to view a set of originals, or to the State Library of Victoria for the microfilm.

Like everyone during the gold rush, the Chinese miners needed to be flexible to follow the trail of gold, but they had the additional pressure of dealing with racism and oppression at many of the settlements, meaning they were often encouraged to move on, or even physically driven off their own claims. Robyn says she found plenty of evidence of this in the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser, in fact, the first digitised issue, 4 August 1857, dealt heavily with the topic, as the Buckland Riot had happened in the goldfields near Mt Buffalo just one month earlier. This horrific event saw around 100 European rioters attack Chinese miners, beating, robbing and driving them out of the area. At least three Chinese men died and entire encampments were destroyed. Anti-Chinese sentiment was echoed across all of Victoria’s goldfields from European settlers scared of a culture which was very different to their own, and envious of their effective communal mining methods. The Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser proclaimed “That the diggers as a body have a deep-rooted aversion to their Chinese neighbours, is a fact that cannot now be denied, and that that aversion will find vent in acts of open violence, if legislative interference does not step in to check the evil” (4 August 1857, p. 2).

The Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser also provides vivid descriptions of how hard life was in the Chinese Protectorates, which were camps the authorities had set up to both protect Chinese settlers, and keep them segregated from other communities. An article from 8 September 1857 describes finding “five Chinamen lying in bed, and apparently in the last stage of some cutaneous disease, the nature of which we did not care to inquire into, but which to us bore all the appearance of the much talked of 'leprosy,' while almost every one of those we met seemed to be suffering in a greater or lesser degree, from the same disorder” (p. 2).

However, Robyn notes that among the depressing details there are also positive stories. “One of the social history aspects of reading the paper which is very rewarding and heart-warming is the place of music in people’s lives, even back in 1857 when it was a very primitive location, you can see that general stores were stocking musical instruments alongside tools and essentials, and in the town there were drama groups, ballet and musical performances. Music was big in those communities because when you think about how horribly difficult life was, to go and sit in a pub or a theatre, or even a tent and be entertained by lamplight, that would give you the moral courage to keep going.” Robyn has found more than a hundred mentions of her ancestors, the Whay family in the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser, largely for their involvement in musical groups and with running a dance school, although her great grandfather, Ah Whay was also apparently quite artistic and “came up as being a prize winner at the annual show in 1900 for some craftwork that he made out of forks.”

The biggest hurdle Robyn has encountered with her research is the inconsistency with names. While the lack of literacy in the nineteenth century makes irregular spelling an issue even for those from English speaking backgrounds, “for the Chinese, because their languages are tonal and written in characters, it was especially difficult for Europeans to write down. So you really have to rack your brain to think how many ways could this name have been written or understood.” She has also encountered ancestors who were incredibly hard to research because they changed their names completely, such as her great great grandfather Hin Yung, who had to become Robert Patrick in order to marry her Irish Catholic great great grandmother, Bridget Delahunty. Language barriers and social attitudes at the time also meant that Chinese people often were not named at all. From newspaper articles through to passenger lists for immigration ships, they were often simply referred to by generic terms such as “Chinaman.”

Robyn says that having the support of the Chinese Australian Family Historians of Victoria (CAFHOV) has been a huge help in dealing with these research difficulties. The group, which has grown to 42 members, meets monthly at the Chinese Museum in Melbourne and is a space for people to share their discoveries and pick the brains of other researchers, as well as guest academics. “Since 2001 when we formed, I’ve seen people making amazing discoveries, even tracing their history back to family villages in China, and visiting their ancestral temples and living relatives.” And it all starts with the original documents; the rate books, hospital records and newspapers providing the clues that allow researchers to dig deeper and deeper into the past. Robyn and CAFHOV hope that with the Maryborough & Dunolly Advertiser’s early issues now easily accessible on Trove, many more researchers with a connection to Maryborough’s goldfields will have a chance to uncover their family history too.

The 2019-2020 round of Local History Grants has just opened for applications. Follow the link below for more information on how to submit your project: prov.vic.gov.au/community/grants-and-awards/local-history-grants-program

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples